Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instruction Manual Instruction Piezas De Repuesto Se Pueden Encontrar En Línea

1 www.AromaCo.com/Support . ARC-687D-1NG found online. Visit online. found replacement parts can be be can parts replacement questions and even even and questions Manual de instrucciones Answers to many common common many to Answers La arrocera favorita de los Estados Unidos Arrocera y vaporera 1-800-276-6286 . ¿Preguntas o dudas acerca Call us toll-free at toll-free us Call de su arrocera? experts are happy to help. to happy are experts Antes de regresar a la tienda... Aromas customer service service customer Aromas Nos expertos de servicio al cliente Before returning to the store... the to returning Before estará encantado de ayudarle. Llámenos al número gratuito a about your rice cooker? rice your about 1-800-276-6286. Questions or concerns concerns or Questions Americas Favorite Rice Cooker Rice Favorite Americas Rice Cooker & Food Steamer Food & Cooker Rice Las respuestas a muchas preguntas comunes e incluso Instruction Manual Instruction piezas de repuesto se pueden encontrar en línea. Visita: www.AromaCo.com/Support. ARC-687D-1NG 54 Todos los derechos reservados. derechos los Todos ©2012 Aroma Housewares Company Housewares Aroma ©2012 www.AromaCo.com 1-800-276-6286 U.S.A. San Diego, CA 92121 CA Diego, San 6469 Flanders Drive Flanders 6469 Aroma Housewares Co. Housewares Aroma Congratulations on your purchase of the Aroma® 14-Cup Digital Rice Cooker. In no time at all, youll be making fantastic, restaurant-quality rice at the touch of a button! Por: Publicada Whether long, medium or short grain, this cooker is specially calibrated to prepare all varieties of rice, including tough-to-cook whole grain brown rice, to uffy perfection. -

National Wages and Productivity Commission

NATIONAL WAGES AND PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION Regional Productivity Accomplishment Report List of Beneficiary Firms - TRAINING Regional Tripartle Wages and Productivity Board-All Regions Region Month Training Program Name of Beneficiary Firm NCR February Lean Management Zachy's Sweetreats Pastillas Collection NCR February Lean Management Hansei Corporation (NCR) NCR February Lean Management Travel Peepers NCR February Lean Management Abby Shoes Manufacturing NCR February Lean Management Staycee's Tea House NCR February Lean Management Aviona's Gourmet Hub NCR February Lean Management BW Shipping Philippines Inc. NCR February Lean Management Zulit Sarap Negosyo NCR February Lean Management Ely-Knows Enterprises NCR February Lean Management Tropical Palm Herb Manufacturing NCR February Lean Management Estipular- Estrada Catering Services NCR February Lean Management Alliedcor Multitech and Energy Corporation NCR February Lean Management Camanava Tiles Center NCR February Lean Management JDP Fruits Korner NCR February Lean Management Drix's Peanut Butter NCR February Lean Management Jobb & Jedd Food Stall NCR February Lean Management Inspecit, Inc. NCR February Lean Management Euroeast Marketing NCR February Lean Management Nicole and Abby Flowers & Gifts NCR February Lean Management Genesis Hot Pandesal NCR February Lean Management Orange Circle Food Enterprise NCR February Lean Management Marc Daniel's Food Products NCR February Lean Management Mishees Event Services NCR February Lean Management SteakTime Char.Grill NCR February Lean Management Tongo's Catering Services NCR February Lean Management Pikache Food Service NCR February Lean Management Vien's Cakes NCR February 7S of Good Housekeeping Dream Riser Builders Inc. NCR February 7S of Good Housekeeping Smartpark Systems Solutions, Inc. NCR February 7S of Good Housekeeping C.O.L. -

2021 United Way Cookbook Index

Index Ahi Carpaccio ........................................................................................... 1 Almond Graham Crackers .................................................................... 121 Aunty Elaine’s Magic Jello .................................................................... 122 Baby Arugula and Watermelon Summer Salad ...................................... 21 Baked Chicken ....................................................................................... 55 Baked Shoyu Chicken ............................................................................ 56 Baked Spaghetti ..................................................................................... 57 Baked Sushi ........................................................................................... 22 Baked Tofu.............................................................................................. 59 Baked Tofu (Ornish Friendly) .................................................................. 58 Balsamic Glaze..................................................................................... 148 Banana Bread....................................................................................... 123 Banana Muffins with Fancy Topping ..................................................... 124 BBQ Hamburger Patties ......................................................................... 60 Beef or Chicken Broccoli ........................................................................ 61 Beef Stew .............................................................................................. -

Good Ole Favorites

Seafood Appetizers Seafood Platters Seafood Specialties Good Ole Favorites Seafood Gumbo Served with Fries, Coleslaw and Hushpuppies All specials served with Fries, Coleslaw and Hushpuppies Served with Fries, Coleslaw and Hushpuppies Cup Bowl Bubba’s “Shrimp Boat” Platter Seafood Medley Fresh Tuna Dip “Bubba Loves it!” Bubba’s famous shrimp cooked four ways! Grilled White Fish, Grilled Shrimp and a Grilled Crab Cake Topped with Fried Crab Claws Our Secret Shrimp Sauce Bubba’s Fried Shrimp Fried • Grilled • Boiled • Blackened Big shrimp fried to perfection ! Grilled Shrimp The Bubba Big Bubba Bubba’s “Fisherman Seafood” Platter Fresh Gulf Shrimp grilled with Bubba’s Special Spices Firecracker Shrimp Cup of Gumbo Popcorn Shrimp lightly dusted, fried and tossed in our spicy sauce Golden Fried Oysters Fried Oysters, Fried Shrimp, Gulf Oysters fried to perfection Fried Fish and Fried Crab Cake Shrimp and Gouda Grits All your favorites in one dinner! A Southern Tradition Fried Fish Platter Oysters on the Half Shell* Fresh Shrimp sauteed in a cream base with garlic and spinach. Served with Fries, Coleslaw and Hushpuppies 1/2 Dozen 1 dozen Served with our homemade Gouda Grits. The Bubba Big Bubba A Bubba Favorite! Large Fresh Boiled Shrimp Captain’s Platter 1/2 Pound 1 pound Crab Legs, Grilled Shrimp and Served Cold Chargrilled Mahi Mahi Crab Claw Dinner Crab Cake Dinner All You Care to Eat Served with Corn on the Cob, New Potatoes Tender Gulf claws seasoned and fried Fresh cakes seasoned with our Cajun Specials and Garlic Butter on the side golden brown. Creole Seasoning, sauteed on the grill Good Ole Appetizers and served with remoulade sauce. -

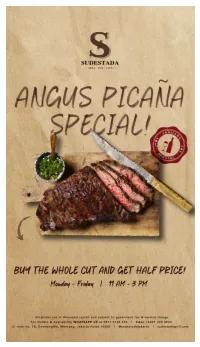

Sudestada-ALL-Menu-2.Pdf

est. 2019 ALL DAY MENU #SudestadaJakarta BIENVENIDO A SUDESTADA JAKARTA Welcome to SUDESTADA JAKARTA, a specialty Argentinian Grill, Bar and Cafe inspired by the vivacious Latin culture. SUDESTADA /su.des.ta.da/ (n.) “powerful wind, particularly the cool strong breeze before a mighty storm” is regarded as an auspicious name in Argentinian culture that brings good luck. Bringing vibrant Argentinian charm to Jakarta’s Aer a taste of our honest cuisine and being culinary scene, Sudestada's guests can expect a immersed in the enchanting neoclassical wholesome and authentic dining experience. ambiance, the wines and the culture, you may Under the helm of our well-seasoned executive come as a guest, but you will leave as el amigo. chef, Victor Taborda, an Argentine native with his team of experienced cooks, their passion and Buen provecho, hope create a new benchmark for Latin culinary oerings, taking them to new heights with contemporary touches that translates from the Enjoy�Your�Meal! plate to your palate. @sudestadajakarta 1 Chef Victor is an Argentinian native of Neuquen, a beautiful town on northern Patagonia. Spent his childhood helping out in his father’s steakhouse has allowed Victor to absorb the concepts of Argentinian Asado by blood. He shares his profound love for his country and its remarkable cuisine to a wider audience who are constantly hungry for food and authentic experiences, Jakarta and beyond. Chef Victor Taborda Argentinian Style Pizzas PIZZAS ARGENTINAS NAPOLITANA Tomatoes, oregano, green olives ..................... 140 PEPPERONI Beef pepperoni .................................................. 150 MORRONES Y JAMON Red bell peppers and ham ................... 170 MOZZARELLA Tomato sauce and olives ............................... -

Crisostomo-Main Menu.Pdf

APPETIZERS Protacio’s Pride 345 Baked New Zealand mussels with garlic and cheese Bagumbayan Lechon 295 Lechon kawali chips with liver sauce and spicy vinegar dip Kinilaw ni Custodio 295 Kinilaw na tuna with gata HOUSE SPECIAL KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Tinapa ni Tiburcio 200 310 Smoked milkfish with salted egg Caracol Ginataang kuhol with kangkong wrapped in crispy lumpia wrapper Tarsilo Squid al Jillo 310 Sautéed baby squid in olive oil with chili and garlic HOUSE SPECIAL KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Calamares ni Tales 325 Fried baby squid with garlic mayo dip and sweet chili sauce Mang Pablo 385 Crispy beef tapa Paulita 175 Mangga at singkamas with bagoong Macaraig 255 Bituka ng manok AVAILABLE IN CLASSIC OR SPICY Bolas de Fuego 255 Deep-fried fish and squid balls with garlic vinegar, sweet chili, and fish ball sauce HOUSE SPECIAL KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Lourdes 275 Deep-fried baby crabs SEASONAL Sinuglaw Tarsilo 335 Kinilaw na tuna with grilled liempo Lucas 375 Chicharon bulaklak at balat ng baboy SIZZLING Joaquin 625 Tender beef bulalo with mushroom gravy Sisig Linares 250 Classic sizzling pork sisig WITH EGG 285 Victoria 450 Setas Salpicao 225 Sizzling salmon belly with sampalok sauce Sizzling button mushroom sautéed in garlic and olive oil KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Carriedo 385 Sautéed shrimp gambas cooked -

Revista Filipina–Primavera 2016

Revista Filipina • Primavera 2016 • Vol. 3, Número 1 RF Revista Filipina Primavera 2016 Volumen 3 • Número 1 Revista semestral de lengua y literatura hispanofilipina http://revista.carayanpress.com Dirigida por Edmundo Farolán desde 1997. ISSN: 1496-4538 Segunda Etapa RF Comité editorial: Director: Edmundo Farolán Subdirector: Isaac Donoso Webmáster: Edwin Lozada Redacción: Jorge Molina, David Manzano y Jeannifer Zabala Comité científico: Pedro Aullón de Haro Florentino Rodao Universidad de Alicante Universidad Complutense de Madrid Joaquín García Medall Joaquín Sueiro Justel Universidad de Valladolid Universidad de Vigo Guillermo Gómez Rivera Fernando Ziálcita Academia Filipina de la Lengua Española Universidad Ateneo de Manila Copyright © 2016 Edmundo Farolán, Revista Filipina Fotografía de la portada: Una vista de Taal. Omar Paz 1 Revista Filipina • Primavera 2016 • Vol. 3, Número 1 RF EDITORIAL HOMENAJE A GUILLERMO GÓMEZ RIVERA edicamos este número especial al quijote filipino, Guillermo Gómez Rivera, un gran caballero, recientemente galardonado por el Grupo de Investigación Human- ismo-Europa de la Universidad de Alicante de España con el Premio José Rizal de Dlas Letras Filipinas. Gómez Rivera verdaderamente merece este gran Premio por su labor de más de sesenta años de promulgar las letras hispanofilipinas. En un homenaje que le hice hace quince años (Revista Filipina, Primavera 2000), he escrito sobre nuestras andanzas, él cual Quijote y yo su Sancho Panza, en un homenaje poético. Hoy a sus 80 años celebramos la grandeza de este escritor infatigable, y para mí, per- sonalmente, un amigo y maestro. En 1967, cuando mi amigo Tony Fernández (q.e.p.d.) escribió en El Debate sobre la publicación en Madrid de mi primer libro de versos, Lluvias Filipinas, él en seguida puso el mismo artículo en su revista El Maestro. -

Kitchen Menu

N U EDAMAME A S I A N K I T C H E N SUSHI H O T A P P E T I Z E R S 4.25 E D A M A M E 4.00 T E M P U R A 6.00 Immature soybeans steamed Lightly battered vegetable in the pod *Add shrimp for $$2 3 6.00 8.00 4.99 S P R I N G R O L L S 4 . 0 0 V O L C A N O 7.00 Minced pork and shrimp Tempura fried veggies and rolled in a thin pastry shrimp topped with spicy (3 pieces) sauce 6.00 6.00 5.25 7.00 L U M P I A 5 . 2 5 A G E D A S H I T O F U 6 . 0 0 Filipino spring rolls with pork Fried tofu served in a light and shrimp (5 pieces) soy/seaweed broth 6.00 7.00 G Y O Z A 6.50 6 . 0 0 C R I S P Y S Q U I D 8.00 7 . 0 0 5 pork dumplings Fried calamari with curry and - Steamed or Fried jalapeno C O L D A P P E T I Z E R S 4.00 5.00 C U C U M B E R S A L A D 3 3.50 I K A S A N S A I 4.00 Thinly sliced marinated Calamari and Japanese cucumber vegetables seasoned with a - $2$1 to add shrimp or octopus sesame vinaigrette 9.00 4.50 4.00 C E V I C H E * 8 . -

Soup, Salad and Appetizer Main Course

Soup, Salad and Appetizer CHUNKY TOMATO SOUP 640 CLASSIC CAESAR SALAD 590 with grilled cheese sandwich Bacon, croutons and shaved Parmesan - with pan seared ‘Pamora’ free-range chicken supreme 750 WONTON NOODLE SOUP 580 - with Cajun-spiced black tiger prawns 880 Chicken broth, shrimp and pork dumplings THE PENINSULA COBB SALAD 880 NEW ENGLAND CLAM CHOWDER 540 ‘Pamora’ free range chicken, cherry tomato, spring onion bacon, avocado, quail egg, Roquefort cheese, sherry dressing THE LOBBY BENTO BOX 1,180 Assorted sushi and sashimi, pickled ginger SESAME ‘PAMORA’ CHICKEN SALAD 750 wasabi and soya Pan seared free-range chicken, garden greens, roasted peanuts sesame dressing, crispy wontons RICE PAPER ROLL 530 WITH MINT AND GARDEN VEGETABLES Carrot, Enoki mushroom, cucumber, white turnip sweet chili coriander dip Main Course OVEN-BAKED ATLANTIC SALMON 980 WILD MUSHROOM PENNE PASTA 780 Quinoa, peas, tomato-vierge emulsion Creamy wild mushroom sauce, snow peas heirloom tomato confit, parmesan cheese “36 HOUR” BRAISED U.S. BEEF SHORTRIB 1,150 CHICKEN POT PIE 750 Truffled potato mousseline, root vegetables, Shiraz jus Creamy braised chicken, potato, pearl onions, peas, carrot, puff pastry THE PENINSULA SCHUEBLIG SAUSAGE 820 SPAGHETTI N° 5 PASTA 740 Choice of chunky tomato sauce, carbonara sauce Grilled or pulutan style (braised with spicy catsup and onions) or beef Bolognese - denotes “Naturally Peninsula” light and healthy cuisine Prices are subject to VAT, 10% service charge and applicable local tax Local Favorites BISTEK TAGALOG 820 GAMBAS AL -

Valentines Menu 14022020

VALENTINE’S MENU (February 14, 2020) 4 Course Set Menu available from 6pm to 9:45pm £45 including a glass of champagne or a glass of red/white wine or Valentine’s cocktail “Pasyon” Chef Jeremy’s special Hors d’oeuvre Soup SUAM NA HALAAN AT MAIS Clam broth served with roasted corn kernels and fried chili leaves Appetizers SAN MIGUEL CAMARON REBOSADO Sam Miguel beer battered deep fried shrimp served with Crab Fat Aioli or SOY BRAISED SAYOTE (V, VE) Fragrant soy braised chayote stuffed with tofu, spinach and cashews or SMOKED BANGUS PATE Creamy smoked milkfish on pandesal chips topped with hollandaise sauce Entremet Citrus sherbet with ginger bits Main Courses BISTEK KINILAW Grill-seared sirloin steak dressed in spiced cane vinegar and sisig vinaigrette or PORK BELLY HUMBA Visayan Braised pork belly cooked in soy sauce, vinegar and aromatics served with banana blossoms, peanuts and plantain or SEAFOOD BICOL EXPRESS Combination of prawns, squid, mussels and shrimp cooked in coconut milk and served with rice or RED PEPPER STUFFED WITH SPICY BIHON NOODLES (V,VE) Roasted red pepper stuffed with paprika spiced rice noodles and peanuts served with a peanut sauce Dessert UBE MOUSSE WITH WHITE CHOCOLATE Creamy dessert made with whipped egg whites and cream flavoured with purple yam and white chocolate or BAKED ALASKA Dulce de leche buttercream ice cream dessert covered with scorched meringue or CHAMPORADO Filipino chocolate rice pudding Coffee or Tea with Petit Fours A discretionary service charge of 12.5% will be added to your bill . -

Nsm 3Q 2014.Pdf

JOHN G. BONGAT JASON B. NEOLA City Mayor Senior Writer Vol. 6, No. 3 | July - September 2014 NELSON S. LEGACION City Vice Mayor RAFAEL RACSO V. VITAN A Quarterly Magazine of the Layout and Design City Government of Naga Bicol, Philippines SIEGLINDE BORROMEO-BULAONG ANSELMO B. MAÑO ISSN 2094-9383 Editor Website Administrator The ROTUNDA at Concepcion Pequeña welcomes all guests and weary travellers coming from and going to all the four directions leading to the City with the warm and environment-friendly topiary image of the Virgin of Peñafrancia, Patroness of Bicolandia! This magazine is published FLORENCIO T. MONGOSO, JR. JOSE B. PEREZ by the City Government of REUEL M. OLIVER ALLEN L. REONDANGA Naga, thru the Ciy Publication Editorial Consultants PAUL JOHN F. BARROSA Office and the City Events, Technical Advisers Protocol and Public Information Office, JOSE V. COLLERA with editorial office at City Hall Compound, XERES RAMON A. GAGERO ALDO NIÑO I. RUIVIVAR J. Miranda Avenue, Naga City SYLRANJELVIC C. VILLAFLOR MAUREEN S. ROJO 4400 Philippines Photographers Staff Assistants Tel: +63 54 472-2136 Email: [email protected] Web: www.naga.gov.ph TABLE OF CONTENTS COVER STORY NAGA -- PH’s 3RD MOST COMPETITIVE CITY; NO.1 IN GOVERNMENT EFFICIENCY 3 THE PASSING OF A BELOVED ARCHBISHOP 6 FLAGS AT HALF-STAFF FOR ARCHBISHOP LEGASPI 7 MAYOR’S TRIBUTE 9 THE NEW ARCHBISHOP’S LIFE OF SERVICE The “Naga SMILES to the World” logo is composed of the two PEÑAFRANCIA FESTIVAL/TOURISM baybayin characters, na and ga. 10 FIESTA! A MOSAIC OF COLORFUL EVENTS Na, shaped like a mountain, P MISS BICOLANDIA 2014 provides a strong foundation for the P TRASLACION Narra tree which grew abundantly P 2ND REGIONAL BAND/MAJORETTE/FANCY DRILL COMPETITION along the Naga River while a zigzag P REGIONAL BSP/GSP PARADE line denotes the majestic Malabsay P CIVIC PARADE AND FLOAT COMPETITION Falls. -

Sushi Menu Sushi Bar Combo Classic Rolls

Spicy Sushi Rice Bowl / $23 Select chopped raw fish with assorted vegetables over steamed rice Sushi Bento Box / $25 Green Mussel (2pc), Seaweed Salad, Nigiri (3pc), Sashimi (6pc), Crunch Munch Roll 9326 Cedar Center Way All Side Sauces (2 oz.) / $0.75 Louisville, KY 40291 Phone: (502) 708-1500 www.sakeblue.com Classic Rolls Sushi Menu The MJ / $13 Spicy crawfish, fresh jalapeño, cream cheese, mozzarella cheese, spicy & eel sauce. Deep fried. Rainbow / $12 California roll with four kinds of fish fillets Snow Roll / $12 Spicy crab topped with salmon with wasabi sauce, crunch Sushi Bar Combo Fire Dragon / $13 Eel & cucumber topped with spicy tuna, sliced avocado, special hot sauce & soy sauce Heaven Roll / $11 Sashimi A / $20 Fried shrimp & cream cheese topped with mango, tuna with wasabi sauce & eel sauce 3 kinds of Sashimi, 3 pcs each Fried Shrimp / $11 Sashimi B / $28 Fried shrimp, crab, masago, avocado, cucumber, sweet soy sauce 4 kinds of Sashimi, 4 pcs each Crispy Dynamite Roll / $12 Sushi Combo A / $20 Spicy tuna, eel, asparagus, deep fried and topped with spicy mayo and 7pc sushi, Tuna Roll eel sauce Sushi Combo B / $29 California / $6 7pc sushi, 8pc Sashimi & Tuna Roll Crab, avocado, cucumber, masago (Spicy Crab $2) Sushi Combo C / $40 Dynamite Roll / $8 7pc sushi, 12pc Sashimi, California Roll, Cucumber Roll Five different kinds of fish tossed in spicy sauce Deluxe Combo / $60 Green Castle Roll / $12 12pc sushi, 15pc Sashimi, California Roll, Tuna Roll, Crunch Munch Tuna, salmon, green avocado. Wrapped with green soybean paper, white Roll sauce and green crunch Supreme Combo / $80 Cha-Cha / $13 20pc sushi, 20pc Sashimi, California Roll, Spicy Tuna Roll, Crunch Shrimp, crab, cream cheese, asparagus.