Download Article In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voting for the Devil You Know: Understanding Electoral Behavior in Authoritarian Regimes

VOTING FOR THE DEVIL YOU KNOW: UNDERSTANDING ELECTORAL BEHAVIOR IN AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Natalie Wenzell Letsa August 2017 © Natalie Wenzell Letsa 2017 VOTING FOR THE DEVIL YOU KNOW: UNDERSTANDING ELECTORAL BEHVAIOR IN AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES Natalie Wenzell Letsa, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 In countries where elections are not free or fair, and one political party consistently dominates elections, why do citizens bother to vote? If voting cannot substantively affect the balance of power, why do millions of citizens continue to vote in these elections? Until now, most answers to this question have used macro-level spending and demographic data to argue that people vote because they expect a material reward, such as patronage or a direct transfer via vote-buying. This dissertation argues, however, that autocratic regimes have social and political cleavages that give rise to variation in partisanship, which in turn create different non-economic motivations for voting behavior. Citizens with higher levels of socioeconomic status have the resources to engage more actively in politics, and are thus more likely to associate with political parties, while citizens with lower levels of socioeconomic status are more likely to be nonpartisans. Partisans, however, are further split by their political proclivities; those that support the regime are more likely to be ruling party partisans, while partisans who mistrust the regime are more likely to support opposition parties. In turn, these three groups of citizens have different expressive and social reasons for voting. -

![Download Article [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1016/download-article-pdf-821016.webp)

Download Article [PDF]

60 JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS ELECTION MANAGEMENT IN CAMEROON Progress, Problems And Prospects Thaddeus Menang Thaddeus Menang is Advisor at the National Elections Observatory P O Box 13506, Yaoundé, Cameroon Tel.: + 237 771 55 71 e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Judged by internationally accepted norms and standards election management in Cameroon stands out as peculiar in more than one respect. Firstly, election management tasks are performed by a multiplicity of bodies and institutions, making it difficult to determine who is really responsible at each stage of the process. Secondly, the conduct of elections is governed by a battery of cross-referencing laws which election stakeholders often find hard to interpret and apply. The problems arising from this situation need to be and are, presently, being addressed within the framework of reforms that target, on the one hand, the adoption of a single, updated and enforceable electoral law and, on the other, the setting up of a viable election management body and the introduction of modern management methods. INTRODUCTION Whereas in the older and better-established democracies of the world election management has become a routine that, more often than not, produces satisfactory results, most of the budding democracies of the Third World are still grappling with the problem of determining which election management procedures are best suited to their specific national contexts. The older democracies themselves tend to differ one from the other, not only in terms of the electoral systems they have put in place but also as regards the specific election management procedures they have adopted. These variations raise the question of whether the management of elections in a democratic context can be said to be governed by a set of internationally accepted norms and standards. -

Journal 3.1 Osaghae

74 JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS INDEPENDENT CANDIDATURE AND THE ELECTORAL PROCESS IN AFRICA Churchill Ewumbue-Monono Dr Churchill Ewumbue-Monono is Minister-Counsellor in the Cameroon Embassy in Russia UI Povarskaya, 40, PO Box 136, International Post, Moscow, Russian Federation Tel: +290 65 49/2900063; Fax: +290 6116 e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study reviews the participation of independent, non-partisan candidates in Africa. It examines the development of competitive elections on the continent between 1945 and 2005, a period which includes both decolonisation and democratic transition elections. It also focuses on the participation of independent candidates in these elections at both legislative and presidential levels. It further analyses the place of independent candidature in the continent’s future electoral processes. INTRODUCTION The concept of political independence, whether it refers to voters or to candidates, describes an individual’s non-attachment to and non-identification with a political party. Generally, voter-centred political independence takes the form of independent voters who, when registering to vote, do not declare their affiliation to a political party. There are also swing or floating voters, who vote independently for personalities or issues not for parties, and switch voters, who are registered voters with a history of crossing party lines. Furthermore, candidate-centred political independence may take the form of apolitical, independent, non-partisan candidates, as well as official and unofficial party candidates (Safire 1968, p 658). The recognition of political independence as a feature of the electoral process has led to the involvement of ‘independent personalities’ in managing election institutions. Examples are ‘independent judiciaries’, ‘independent electoral commissions’, and ‘independent election observers’. -

2018 EISA Annual Report

EISA ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Annual Report 2018 Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa i Annual Report 2018 iii EISA ANNUAL REPORT 2018 about eisa TYPE OF ORGANISATION EISA is an independent, non-profit non-partisan non- governmental organisation whose focus is elections, OUR VISION democracy and governance in Africa. AN AFRICAN CONTINENT WHERE DATE OF ESTABLISHMENT DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE, July 1996. HUMAN RIGHTS AND CITIZEN OUR PARTNERS PARTICIPATION ARE UPHELD IN A Electoral management bodies, political parties, civil society PEACEFUL ENVIRONMENT. organisations, local government structures, parliaments, and national, Pan-African organisations, Regional OUR MISSION Economic Communities and donors. EISA STRIVES FOR EXCELLENCE OUR APPROACH IN THE PROMOTION OF Through innovative and trust-based partnerships throughout the African continent and beyond, EISA CREDIBLE ELECTIONS, CITIZEN engages in mutually beneficial capacity reinforcement PARTICIPATION, AND THE activities aimed at enhancing all partners’ interventions in STRENGTHENING OF POLITICAL the areas of elections, democracy and governance. INSTITUTIONS FOR SUSTAINABLE OUR STRUCTURE DEMOCRACY IN AFRICA. EISA consists of a Board of Directors comprised of stakeholders from the African continent and beyond. The Board provides strategic leadership and upholds financial accountability and oversight. EISA has as its patron Sir Ketumile Masire, the former President of Botswana. The Executive Director is supported by an Operations Director and Finance and Administration Department. EISA's focused programmes include: Elections and Political Processes Balloting and Electoral Services Governance Institutions and Processes Supporting Transitions and Electoral Processes Programme In 2018 EISA had 7 field offices, namely, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Madagascar, Mali, Mozambique, Somalia, and Zimbabwe and a Central Africa regional office (Gabon). -

Post-Conflict Elections”

POST-CONFLICT ELECTION TIMING PROJECT† ELECTION SOURCEBOOK Dawn Brancati Washington University in St. Louis Jack L. Snyder Columbia University †Data are used in: “Time To Kill: The Impact of Election Timing on Post-Conflict Stability”; “Rushing to the Polls: The Causes of Early Post-conflict Elections” 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. ELECTION CODING RULES 01 II. ELECTION DATA RELIABILITY NOTES 04 III. NATIONAL ELECTION CODING SOURCES 05 IV. SUBNATIONAL ELECTION CODING SOURCES 59 Alternative End Dates 103 References 107 3 ELECTION CODING RULES ALL ELECTIONS (1) Countries for which the civil war has resulted into two or more states that do not participate in joint elections are excluded. A country is considered a state when two major powers recognize it. Major powers are those countries that have a veto power on the Security Council: China, France, USSR/Russia, United Kingdom and the United States. As a result, the following countries, which experienced civil wars, are excluded from the analysis [The separate, internationally recognized states resulting from the war are in brackets]: • Cameroon (1960-1961) [France and French Cameroon]: British Cameroon gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1961, after the French controlled areas in 1960. • China (1946-1949): [People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan)] At the time, Taiwan was recognized by at least two major powers: United States (until the 1970s) and United Kingdom (until 1950), as was China. • Ethiopia (1974-1991) [Ethiopia and Eritrea] • France (1960-1961) [France -

The Democratic Challenge in Africa

The Democratic Challenge in Africa The Carter Center The Carter Center May, 1994 Introduction On May 13-14, 1994, a group of 32 scholars and practitioners took part in a seminar on Democratization in Africa at The Carter Center. This consultation was a sequel to two similar meetings held in February 1989 and March 1990. Discussion papers from those seminars have been published under the titles, Beyond Autocracy in Africa and African Governance in the 1990s. During the period 1990-94, the African Governance Program of The Carter Center moved from discussions and reflections to active involvement in the complex processes of renewed democratization in several African countries. These developments throughout Africa were also monitored and assessed in the publication, Africa Demos. The letter of invitation to the 1994 seminar called attention to the need for a new period of collective reflection because of "the severe difficulties encountered by several of these transitions." "The overriding concern," it was further stated, "will be to identify what could be done to help strengthen the pluralist democracies that have emerged during the past five years and what strategies may be needed to overcome the many obstacles that are now evident." A list of 12 questions was sent to each of the participants with a request that they identify which ones they wished to address in their discussion papers. As it turned out, the choice of topics could be conveniently grouped in six panels. Following the seminar, 19 of the participants revised their papers for publication in this volume, while an additional four scholars (John Harbeson, Goran Hyden, Timothy Longman, and Donald Rothchild), who had been unable to attend the meeting, still submitted papers for discussion and publication. -

The Pseudo-Democrat's Dilemma: Why Election Observation Became an International Norm

THE PSEUDO- DEMOCRAT’S DILEMMA THE PSEUDO- DEMOCRAT’S DILEMMA WHY ELECTION OBSERVATION BECAME AN INTERNATIONAL NORM Susan D. Hyde CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Cornell University Press gratefully acknowledges receipt of a grant from the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale University, which helped in the publication of this book. The book was also published with the assistance of the Frederick W. Hilles Publication Fund of Yale University. Copyright © 2011 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2011 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hyde, Susan D. The pseudo-democrat’s dilemma : why election observation became an international norm / Susan D. Hyde. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-4966-6 (alk. paper) 1. Election monitoring. 2. Elections—Corrupt practices. 3. Democratization. 4. International relations. I. Title. JF1001.H93 2011 324.6'5—dc22 2010049865 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fi bers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. -

Cameroon Version 4 Clean#2

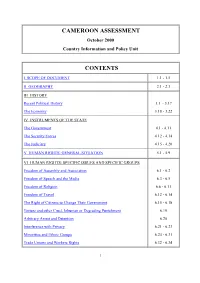

CAMEROON ASSESSMENT October 2000 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.3 III HISTORY Recent Political History 3.1 - 3.17 The Economy 3.18 - 3.22 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE The Government 4.1 - 4.11 The Security Forces 4.12 - 4.14 The Judiciary 4.15 - 4.20 V HUMAN RIGHTS: GENERAL SITUATION 5.1 - 5.9 VI HUMAN RIGHTS: SPECIFIC ISSUES AND SPECIFIC GROUPS Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.1 - 6.2 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.3 - 6.5 Freedom of Religion 6.6 - 6.11 Freedom of Travel 6.12 - 6.14 The Right of Citizens to Change Their Government 6.15 - 6.18 Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Punishment 6.19 Arbitrary Arrest and Detention 6.20 Interference with Privacy 6.21 - 6.23 Minorities and Ethnic Groups 6.24 - 6.31 Trade Unions and Workers Rights 6.32 - 6.34 1 Human Rights Groups 6.35 - 6.36 Women 6.36 - 6.41 Children 6.42 - 6.45 Treatment of Refugees 6.46 - 6.48 ANNEX A: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS Pages 19 - 22 ANNEX B: PROMINENT PEOPLE Page 23 ANNEX C: CHRONOLOGY Pages 24 - 27 ANNEX D: BIBLIOGRAPHY Pages 28 - 29 I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. -

The Constitution and Governance in Cameroon

The Constitution and Governance in Cameroon This book provides a systematic analysis of the major structural and institutional governance mechanisms in Cameroon, critically analysing the constitutional and legislative texts on Cameroon’s semi-presidential system, the electoral system, the legislature, the judiciary, the Constitutional Council and the National Commission on Human Rights and Freedoms. The author offers an assessment of the practical application of the laws regulating constitutional institutions and how they impact on governance. To lay the groundwork for the analysis, the book examines the historical, constitutional and political context of governance in Cameroon, from independence and reunification in 1960–1961, through the adoption of the 1996 Constitution, to more recent events including the current Anglophone crisis. Offering novel insights on new institutions such as the Senate and the Constitutional Council and their contribution to the democratic advancement of Cameroon, the book also provides the first critical assessment of the legislative provisions carving out a special autonomy status for the two Anglophone regions of Cameroon and considers how far these provisions go to resolve the Anglophone Problem. This book will be of interest to scholars of public law, legal history and African politics. Laura-Stella E. Enonchong is a Senior Lecturer at De Montfort University, UK. Routledge Studies on Law in Africa Series Editor: Makau W. Mutua The Constitution and Governance in Cameroon Laura-Stella E. Enonchong The Constitution and Governance in Cameroon Laura-Stella E. Enonchong First published 2021 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2021 Laura-Stella E. -

Voter Identification Requirements and Public International Law: an Examination of Africa and Latin America

Voter Identification Requirements and Public International Law: An Examination of Africa and Latin America One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 404-420-5188 Fax 404-420-5196 www.cartercenter.org 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................................................... 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 8 Voter Identification Practices in Africa and Latin America .................................................................... 9 Africa .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Latin America ...................................................................................................................................... 10 Overall Conclusions ................................................................................................................................ 10 INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS FOR SUFFRAGE ......................................................................................... 13 OVERVIEW OF AFRICA ......................................................................................................................... 15 Preliminary Analysis of African Identification Laws ............................................................................. 16 Recognizing Reality: Flexible Identification Laws -

2013 CET Cameroon Legislative and Municipal Elections Report

Report of the Commonwealth Expert Team CAMEROON LEGISLATIVE AND MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS 30 September 2013 CAMEROON LEGISLATIVE AND MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS 30 September 2013 Table of Contents LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL ........................................................................ iv CHAPTER ONE ........................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER TWO ....................................................................................... 3 POLITICAL BACKGROUND ........................................................................ 3 Recent Political Developments .............................................................. 3 The Candidates ................................................................................. 4 Political Parties ................................................................................. 5 Commonwealth Engagement and Issues .................................................... 5 CHAPTER THREE ..................................................................................... 8 CONSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR ELECTIONS .............................. 8 Constitutional Background .................................................................... 8 Terms of Office and Voting System ......................................................... 8 Election of Members of the National Assembly ........................................... 8 Election of Municipal Councillors -

Opposition Politics and Electoral Democracy in Cameroon, 1992-2007

Africa Development, Vol. XXXIX, No. 2, 2014, pp. 103 – 116 © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, 2014 (ISSN 0850-3907) Opposition Politics and Electoral Democracy in Cameroon, 1992-2007 George Ngwane* Abstract This article seeks to assess the impact of electoral democracy in Cameroon especially in terms of the performance of the Opposition between 1992 and 2007, evaluate the internal shortcomings of opposition parties, and make a projection regarding a vibrant democratic space that will go beyond routine elections to speak to the issues preoccupying the Cameroonian masses. Résumé Cet article vise à évaluer l’impact de la démocratie électorale au Cameroun en particulier en termes de performance de l’opposition entre 1992 et 2007, à évaluer les lacunes internes des partis d’opposition, et à faire une projection concernant un espace démocratique dynamique qui ira au-delà des élections ordinaires pour aborder les questions qui préoccupent les masses camerounaises. Introduction The political history of modern Cameroon can be divided into four periods. The first was the period of total dependence on the colonial power which extended from 1884 to 1945 during which the country did not possess representative institutions. The second period stretched from 1945 to 1960/ 61 during which Cameroonians passed their apprenticeship in democracy. The third started on 1st January 1960, with the proclamation of independence in French Cameroon and the reunification of West and East Cameroons in 1961 in a federal structure, and the fourth saw the light of day on 20 May 1972 when the federal structure was abolished in what the then Head of State, Ahmadou Ahidjo termed the ‘Peaceful Revolution’ (Sobseh Emmanuel 2012:88).