The Constitution and Governance in Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

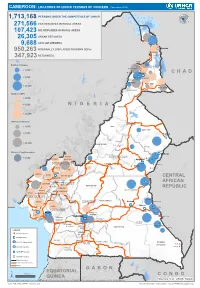

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Cardinal Christian Tumi, Was Cameroon's First Cardinal

30 CATHOLIC NEW YORK April 8, 2021 St. Simon Stock... CONTINUED FROM PAGE 32 Cardinal Farley died. The Carmelites feared the promise of a new parish might have died with the cardinal. However, in April 1919, Father John SPIRITUAL HOME— Cogan, O. Carm., who was the Irish provincial, Faithful parishioners pray made a visit to the new archbishop, Cardinal during the March 20 clos- Patrick Hayes, who assured him the promise of ing Mass celebrating the a parish was still alive. This promise became a 100th anniversary of st. reality in March 1920. simon stock in the Bronx. The first Mass in the new parish was celebrat- auxiliary Bishop Peter ed in “a house on the hill” which was located on Byrne served as principal the southwest corner of 182nd Street and Valen- celebrant and homilist. tine Avenue where the school building now sits. Founded in 1920, the par- Father William G. O'Farrell, a Carmelite from ish has been administered Ireland, who had only been ordained for about from the beginning by three years, was appointed the first pastor of the Carmelite Friars. the the new parish. The first Mass was celebrated in current pastor is Father the house on Palm Sunday, March 28, 1920. The Michael Kissane, o. Carm. church building was constructed in 1921. St. Si- mon Stock School opened in 1926. Nuns from the Sisters of Mercy taught at the Maria r. Bastone school from soon after the opening until the 1970s. Tara Braswell is principal of the K-8 el- education, where about 170 youths are registered. -

Understanding French Foreign and Security Policy Towards Africa: Pragmatism Or Altruism Abdurrahim Sıradağ1

Afro Eurasian Studies Journal Vol 3. Issue 1, Spring 2014 Understanding French Foreign and Security Policy towards Africa: Pragmatism or Altruism Abdurrahim Sıradağ1 Abstract France has deep economic, political and historical relations with Africa, dating back to the 17th century. Since the independence of the former colonial countries in Africa in the 1950s and 1960s, France has continued to maintain its economic and political relations with its former colonies. Importantly, France has a special strategic security partnership with the African countries. It has intervened militarily in Africa more than 50 times since 1960. France has especially continued to use its military power to strengthen its economic, political and strategic relations with Africa. For instance, it deployed its military troops in Mali in January 2013 and in the Central African Republic in December 2013. Why does France actively get involved in Africa militarily? This research will particularly uncover the main motivations behind the French foreign and security policy in Africa. Key words: Francophone Africa, France, Foreign Policy, Africa, economic interests. The Role of France in World Politics France’s international power and position has shaped its foreign and security policy towards Africa. France has been an important actor with its political and economic power in Europe and in the world. It was one of the six important founding members of the European Community after 1 International University of Sarajevo, Department of International Relations, Ilidža, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Email: [email protected] 100 the Second World War and plays a leading role in European integration. France plays a significant role in world politics through international or- ganizations. -

Aerial Surveys of Wildlife and Human Activity Across the Bouba N'djida

Aerial Surveys of Wildlife and Human Activity Across the Bouba N’djida - Sena Oura - Benoue - Faro Landscape Northern Cameroon and Southwestern Chad April - May 2015 Paul Elkan, Roger Fotso, Chris Hamley, Soqui Mendiguetti, Paul Bour, Vailia Nguertou Alexandre, Iyah Ndjidda Emmanuel, Mbamba Jean Paul, Emmanuel Vounserbo, Etienne Bemadjim, Hensel Fopa Kueteyem and Kenmoe Georges Aime Wildlife Conservation Society Ministry of Forests and Wildlife (MINFOF) L'Ecole de Faune de Garoua Funded by the Great Elephant Census Paul G. Allen Foundation and WCS SUMMARY The Bouba N’djida - Sena Oura - Benoue - Faro Landscape is located in north Cameroon and extends into southwest Chad. It consists of Bouba N’djida, Sena Oura, Benoue and Faro National Parks, in addition to 25 safari hunting zones. Along with Zakouma NP in Chad and Waza NP in the Far North of Cameroon, the landscape represents one of the most important areas for savanna elephant conservation remaining in Central Africa. Aerial wildlife surveys in the landscape were first undertaken in 1977 by Van Lavieren and Esser (1979) focusing only on Bouba N’djida NP. They documented a population of 232 elephants in the park. After a long period with no systematic aerial surveys across the area, Omondi et al (2008) produced a minimum count of 525 elephants for the entire landscape. This included 450 that were counted in Bouba N’djida NP and its adjacent safari hunting zones. The survey also documented a high richness and abundance of other large mammals in the Bouba N’djida NP area, and to the southeast of Faro NP. In the period since 2010, a number of large-scale elephant poaching incidents have taken place in Bouba N’djida NP. -

Cameroon – Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 4 March 2011

Cameroon – Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 4 March 2011 What information is there on police corruption, specifically politically motivated corruption, within Cameroon? The 2011 Committee to Protect Journalists annual report on Cameroon states: “Cameroon, which has Central Africa's largest economy, was among the 35 worst nations worldwide on Transparency International's 2010 Corruption Perception Index, which ranks nations on government integrity.” (Committee to Protect Journalists (15 February 2011) Attacks on the Press 2010 – Cameroon) A country profile of Cameroon published on the Business Anti-Corruption Portal website, in a section titled “Political Climate”, states: “Cameroon's President and leader of the ruling Cameroon People's Democratic Movement (CPDM), Paul Biya, has been in power since 1982, having been re elected for a new seven-year term in 2004 with more than 70% of the vote. International observers note that the President's many years with a tight grip on power have facilitated high levels of corruption, nepotism and cronyism that have fuelled extensive patronage systems. The President's ethnic group, the Beti-Bulu, is overrepresented in the government, in the military, as civil servants and in the management of state-owned companies. This feeds a system of endemic graft and ethnic clientelism in an administration that includes more than 60 ministries. Ministerial posts are considered part of the patronage system rather than a rational legal system, and the embezzlement of public funds at high levels of the state hierarchy continues. Public aversion with corruption is growing and, according to Transparency International's Global Corruption Barometer 2009, corruption is perceived to be widespread within the judiciary, political parties, customs, the police, and among civil servants in general, with 55% of the citizens claiming to have paid a bribe in the 6 months prior to the study. -

Status of Lgbti People in Cameroon, Gambia, Ghana and Uganda

STATUS OF LGBTI PEOPLE IN CAMEROON, GAMBIA, GHANA AND UGANDA 3.12.2015 Finnish Immigration Service Country Information Service Public Theme Report 1 (123) Table of contents Disclaimer .................................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1. The colonial legacy of anti-sodomy laws ......................................................................................... 7 1.2. The significance of current laws criminalising same-sex conduct ............................................. 11 1.3. Particularities of the situation of lesbians and bisexual women................................................. 12 1.4. Particularities of the situation of transgender and intersex people ........................................... 14 1.5. Violations of international and regional human rights law .......................................................... 14 2. Cameroon .............................................................................................................................................. 18 2.1. The legal framework ........................................................................................................................ -

CASE STUDY CAMEROON THESIS Aw

T.C. ISTANBUL AYDIN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INVESTIGATION ON CAUSES OF CIVIL WAR: CASE STUDY CAMEROON THESIS Awo EPEY P. Department of Political Science and International Relations Political Science and International Relations Program Thesis Advisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Özüm Sezin UZUN June, 2019 T.C. ISTANBUL AYDIN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INVESTIGATION ON CAUSES OF CIVIL WAR: CASE STUDY CAMEROON M. Sc. THESIS Awo EPEY P. (Y1812.110032) Department of Political Science and International Relations Political Science and International Relations Program Thesis Advisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Özüm Sezin UZUN June, 2019 DEDICATION This work is specially dedicated to my lovely late mother Mami Dorothy Ngkanghe who had always wish to see me climb the academic ladder, and to my dear wife Violet Etona Rokende, my lovely kids Awo Dunia Rouge Nkanghe, Awo Mabel Rouge Oben, and my late junior brother Epey Cyprian Oben, for their constant moral supports. ii FOREWORD Glory to God Almighty who has made this piece of work possible. Except the Lord builds for his people, the builder builds in vain. My deepest appreciation goes to my Supervisor Assist. Prof. Dr. Özüm Sezin UZUN for her effort to the success of this work. “Thank you Doctor” is the supreme statement I can use to express my gratitude. Special thanks goes to my lecturers who directly or indirectly helped me out in this work; Dr.Egemen BAGIS, Prof. Hatice Deniz YUKSEKER, Assist. Prof. Dr. Özüm Sezin UZUN, Dr. Filiz KATMAN, Dr Gökhan DUMAN and all other lecturers in Istanbul Aydin University whose class lectures were very instrumental in the realization of this work. -

The Metaphor of Salt Voters in the Political Landscape of Mamfe During Elections in Cameroon Since 1990

Social Science Review Volume 2, Issue 1, June 2016 ISSN 2518-6825 Enjoying the Booty and Compromising the Future: The Metaphor of Salt Voters in the Political Landscape of Mamfe during Elections in Cameroon Since 1990 Martin Sango Ndeh1 Abstract The political landscape in Cameroon in the 1990s witnessed a transition to multiparty democracy from a single party system. This new era came with its own positive as well as negative virtues of political participation. The fragile nature of democracy which was characterized by the lack of good will to create institutions that will guarantee fair play and a level playing ground for all the political party contenders paved the way for electoral fraud and other vices that are repugnant to the democratic culture. Parties were not formed based on ideology but on regional, ethnic and other undemocratic principles. The government even played a major role in ensuring that some pro-government opposition parties were created so as to penetrate and weaken the strength of the opposition. This was just one of the awful mechanisms that were put in place by the government to offset the balance, jeopardize the foundation of democracy and to maintain the status quo in favour of the incumbent. Apart from granting sponsorship to some opposition leaders the government and the ruling party in some circumstances out rightly bought the people’s conscience in some areas. The government and the ruling party are used inter-changeably in this paper because it is difficult to separate the government from the ruling party particularly when it comes to distinguishing government funds from party funds. -

Human Rights and Constitution Making Human Rights and Constitution Making

HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTION MAKING HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTION MAKING New York and Geneva, 2018 II HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTION MAKING Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: United Nations Publications, 300 East 42nd St, New York, NY 10017, United States of America. E-mail: [email protected]; website: un.org/publications United Nations publication issued by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Photo credit: © Ververidis Vasilis / Shutterstock.com The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a figure indicates a reference to a United Nations document. HR/PUB/17/5 © 2018 United Nations All worldwide rights reserved Sales no.: E.17.XIV.4 ISBN: 978-92-1-154221-9 eISBN: 978-92-1-362251-3 CONTENTS III CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 1 I. CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS AND HUMAN RIGHTS ......................... 2 A. Why a rights-based approach to constitutional reform? .................... 3 1. Framing the issue .......................................................................3 2. The constitutional State ................................................................6 3. Functions of the constitution in the contemporary world ...................7 4. The constitution and democratic governance ..................................8 5. -

Corruption in Cameroon

Corruption in Cameroon CORRUPTION IN CAMEROON - 1 - Corruption in Cameroon © Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Cameronn Tél: 22 21 29 96 / 22 21 52 92 - Fax: 22 21 52 74 E-mail : [email protected] Printed by : SAAGRAPH ISBN 2-911208-20-X - 2 - Corruption in Cameroon CO-ORDINATED BY Pierre TITI NWEL Corruption in Cameroon Study Realised by : GERDDES-Cameroon Published by : FRIEDRICH-EBERT -STIFTUNG Translated from French by : M. Diom Richard Senior Translator - MINDIC June 1999 - 3 - Corruption in Cameroon - 4 - Corruption in Cameroon PREFACE The need to talk about corruption in Cameroon was and remains very crucial. But let it be said that the existence of corruption within a society is not specific to Cameroon alone. In principle, corruption is a scourge which has existed since human beings started organising themselves into communities, indicating that corruption exists in countries in the World over. What generally differs from country to country is its dimensions, its intensity and most important, the way the Government and the Society at large deal with the problem so as to reduce or eliminate it. At the time GERDDES-CAMEROON contacted the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung for a support to carry out a study on corruption at the beginning of 1998, nobody could imagine that some months later, a German-based-Non Governmental Organisation (NGO), Transparency International, would render public a Report on 85 corrupt countries, and Cameroon would top the list, followed by Paraguay and Honduras. - 5 - Corruption in Cameroon Already at that time in Cameroon, there was a general outcry as to the intensity of the manifestation of corruption at virtually all levels of the society. -

Traditional Leadership: Some Reflections on Morphology of Constitutionalism and Politics of Democracy in Botswana

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 1 No. 14; October 2011 TRADITIONAL LEADERSHIP: SOME REFLECTIONS ON MORPHOLOGY OF CONSTITUTIONALISM AND POLITICS OF DEMOCRACY IN BOTSWANA Dr Khunou Samuelson Freddie 1. INTRODUCTION An objective analysis of constitutional model of Botswana has a start from the colonial era within the political relations among the Tswana politicians, traditional leaders and the representatives of the Great Britain. This article seeks to discuss the role of the traditional leaders and politicians in the constitutional construction of Botswana with specific reference to both the 1965 and 1966 constitutions. With the advent of constitutionalism and democracy in Botswana, the role of the institution of traditional leadership was redefined. The constitutional dispensation had a profound impact on the institution of traditional leadership in Botswana and seemingly made serious inroads in the institution by altering the functions, which traditional leaders had during the pre-colonial and colonial periods. For example, constitutional institution such as the National House of Chiefs was established to work closely with the central government on matters of administration particularly those closely related to traditional communities, traditions and customs. This article will also explore and discuss the provisions of both the 1965 and 1966 Constitutions of Botswana and established how they affected the roles, functions and powers of traditional leaders in Botswana. 2. TOWARDS THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONSTRUCTION For many African countries, the year 1960 was the annus mirabilis in which most of them attained independence. Botswana also took an important step towards self-government in the early sixties. In 1959 a Committee of the Joint Advisory Council (JAC) presented a report recommending that this Council should be reconstituted as Legislative Council (LC). -

Country Review Report of Cameroon

Country Review Report of Cameroon Review by the Republic of Angola and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia of the implementation by Cameroon of articles 15 – 42 of Chapter III. “Criminalization and law enforcement” and articles 44 – 50 of Chapter IV. “International cooperation” of the United Nations Convention against Corruption for the review cycle 2010 - 2015 Page 1 of 142 I. Introduction 1. The Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption was established pursuant to article 63 of the Convention to, inter alia, promote and review the implementation of the Convention. 2. In accordance with article 63, paragraph 7, of the Convention, the Conference established at its third session, held in Doha from 9 to 13 November 2009, the Mechanism for the Review of Implementation of the Convention. The Mechanism was established also pursuant to article 4, paragraph 1, of the Convention, which states that States parties shall carry out their obligations under the Convention in a manner consistent with the principles of sovereign equality and territorial integrity of States and of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of other States. 3. The Review Mechanism is an intergovernmental process whose overall goal is to assist States parties in implementing the Convention. 4. The review process is based on the terms of reference of the Review Mechanism. II. Process 5. The following review of the implementation by Cameroon of the Convention is based on the completed response to the comprehensive self-assessment checklist received from Cameroon, supplementary information provided in accordance with paragraph 27 of the terms of reference of the Review Mechanism and the outcome of the constructive dialogue between the governmental experts from Cameroon, Angola and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, by means of telephone conferences, and e-mail exchanges and involving: Angola Dr.