Delhi: Oxford and IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., 1993. Xiv + 185 Pages. 15 Color and 5 B/W Plates, Map, Glossary, Bibliography, Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8. Krishna Karnamrutam

Sincere Thanks To: 1. SrI nrusimha SEva rasikan, Oppiliappan Koil V.SaThakOpan swAmi, Editor- In-Chief of sundarasimham-ahobilavalli kaimkaryam for kindly editing and hosting this title in his eBooks series. 2. Mannargudi Sri.Srinivasan NarayaNan swami for compilation of the source document and providing Sanskrit/Tamil Texts and proof reading 3. The website http://www.vishvarupa.com for providing the cover picture of Sri GuruvAyUrappan 4. Nedumtheru Sri.Mukund Srinivasan,Sri.Lakshminarasimhan Sridhar, www.sadagopan.org www.sadagopan.org Smt.Krishnapriya for providing images. 5. Smt.Krishnapriya for providing the biography of Sri Leela Sukhar for the appendix section and 6. Smt. Jayashree Muralidharan for eBook assembly C O N T E N T S Introduction 1 Slokams and Commentaries 3 Slokam 1 -10 5-25 Slokam 11 - 20 26-44 Slokam 21 - 30 47-67 Slokam 31 - 40 69-84 www.sadagopan.org www.sadagopan.org Slokam 41 - 50 86-101 Slokam 51 - 60 103-119 Slokam 61 - 70 121-137 Slokam 71 - 80 141-153 Slokam 81 - 90 154-169 Slokam 91 - 100 170-183 Slokam 101 - 110 184-201 nigamanam 201 Appendix 203 Brief Biography of Sri Leelaa Sukhar 205 Complete List of Sundarasimham-ahobilavalli eBooks 207 www.sadagopan.org www.sadagopan.org SrI GuruvAyUrappan . ïI>. ïIlIlazukkiv ivrictm! . ïIk«:[k[aRm&tm!. KRISHNAAKARNAAMRTAM OF LEELASUKA X×W www.sadagopan.org ABOUT THE AUTHOR The name of the author of this slokam is Bilavamangala and he acquired the name Leelasuka because of his becoming immersed in the leela of KrishNa and describing it in detail like Sukabrahmarshi. -

Krishnanattam- Glances Across the Screen an Analysis of the Divine Dance Drama Under the Rubric of Cultural Economics

2017/2364 (3) 211 IF : 4.176 | IC Value : 78.46 VOL- (3) ISSUE 211 ISSN 2017/2364 Culture KRISHNANATTAM- GLANCES ACROSS THE SCREEN AN ANALYSIS OF THE DIVINE DANCE DRAMA UNDER THE RUBRIC OF CULTURAL ECONOMICS Prof.K X Joseph || Department of Economics University of Calicut Dr John Mathai Centre Aranattukara Thrissur. Kerala has a composite and cosmopolitan culture which was the contribution of several people and races. When we analyse the cultural history of Kerala we can see the importance of temple art forms. These art forms cater the entertainment of upper castes, mainly Brahmins and Kshatriyas. Kuthu , Krishnanattam, Kathakali and Koodiyattam were the products of this culture. This cultural phenomenon reflects the style of life of the people and it also affects the ‘economic culture’ of the people of Kerala. Krishnanattam- Glances across ,the screen An analysis, of the Divine Divine Dance, Drama under ,the Rubric ,of Cultural Economics. INTRODUCTION on eight successive nights. On the ninth day ‘Avatharam’ was to be presented again and to end the series auspiciously. The importance of this art form in Guruvayoor temple has been attributed to the fact that, it is considered as a prime form of offering Krishnanattam under the rubric of Cultural Economics: by the devotees to the ‘God Krishna’ for the fulfillment of their As Du Mount states, there is a definite relationship between caste and wishes. Krishnanattam, though it owes its origin to ‘Koodi- yattam’, occupation, eventually contributed to the stability of caste system the earliest art form of the dance drama traditions of Kerala, is which is a major hazard in the way of social mobility. -

Chapter Iv Traces of Historical Facts From

CHAPTER IV TRACES OF HISTORICAL FACTS FROM SANDESAKAVYAS & SHORT POEMS Sandesakavyas occupy an eminent place among the lyrics in Sanskrit literature. Though Valmiki paved the way in the initial stage it was Kalidasa who developed it into a perfect form of poetic literature. Meghasandesa, the unique work of Kalidasa, was re- ceived with such enthusiasam that attempts were made to emulate it all over India. As result there arose a significant branch of lyric literature in Sanskrit. Kerala it perhaps the only region which produced numerous works of real merit in this field. The literature of Kerala is full of poems of the Sandesa type. Literature can be made use of to yield information about the social history of a land and is often one of the main sources for reconstructing the ancient social customs and manners of the respective periods. History as a separate study has not been seriously treated in Sanskrit literature. Apart form literary merits, the Sanskrit literature of Kerala contains several historical accounts of the country with the exception of a few historical Kavyas, it is the Sandesakavyas that give us some historical details. Among the Sanskrit works, the Sandesa Kavya branch stands in a better position in this field (matter)Since it contains a good deal of historical materials through the description of the routes to be followed by the messengers in the Sandesakavyas. The Sandesakavyas play an impor- tant role in depicting the social history of their ages. The keralate Sandesakavyas are noteworthy because of the geographical, historical, social and cultural information they supply about the land. -

MA Syllbus 2014 Revised 17 8 14

SYLLABUS FOR M.A. PROGRAMME IN SANSKRIT SAHITYA (2014 June onwards) The syllabus of M.A. programme in Sanskrit Sahitya (Course Credit and Semester System) is being restructured in order to satisfy the contemporary requirements on the basis of the recent developments in the academic field. To provide an interdisciplinary nature to the courses, some areas of studies are developed, changed and/or redefined. M.A. programme is consisted of four semesters. Total number of courses is 20. Each course is having 4 credits. Thus the student has to acquire a minimum total of 80 credits for completing the programme. Among the 20 courses of the PG programme, 7 are electives/optionals out of which 5 should be from the parent department(Internal Electives) and the remaining two must be, from any other departments(multidisciplinary electives). There will be five courses in each semester and five hours are distributred for each course. There will be 3 core courses and two elective/optional course in each semester. In the first and fourth semesters, elective/optional courses are to be taken from within the parent department from the internal electives given in the list and in the second and third, it has to be from other departments. Students of other departments can opt the multidisciplinary elective courses offerd by the Department of Sanskrit Sahitya in the second and third semesters and the students may write answers either in Sanskrit, or in English or in Malayalam The Course 20, ie, ProjectCourse No:1 (Dissertation) will be in the form of the presentation of seminar and a project work done by each and every student. -

C 61200 (Pages : 2)� Name � Reg

C 61200 (Pages : 2) Name Reg. No FOURTH SEMESTER B.A./B.Sc. DEGREE EXAMINATION APRIL 2019 (CUCBCSS—UG) Sanskrit SKT 4A 10—HISTORY OF SANSKRIT LITERATURE, KERALA CULTURE AND TRANSLATION Time ; Three Hours Maximum : 80 Marks Answers may be written either in Sanskrit or in English or in Malayalam. In writing Sanskrit, Devanagari script should be used. I. Answer any ten in one or two words : 1 Who is known as Adikavi ? 2 What does the term "Panivada" indicate ? 3 Who is the author of Raghunathanbhyudaya ? 4 Which temple art form is enacted only by women ? Fill in the blanks with suitable words : 5 is the longest poem ever known in literary history. 6 There are kandas in Ramayana. 7 Narayanabhatta represented school of Mimamsa. 8 Kutiyattam is performed at specially built Temple theatres known as Answer in one word : 9 Which text is composed by Manaveda for Krishnanattam ? .10 Who is the author of Darsanamala ? 11 Name the historical poem written by A.R. Rajaraja Varma ? 12 Mention the art form in which humour is of much importance ? (10 x 1 = 10 marks) II. Write short notes on any five of the following : 13 Valmiki. 14 Rajatarangini. 15 Bharatachampu. 16 Sree Narayana Guru. 17 Yasastilaka Champu. 18 Punnasseri Nambi. 19 Chakyarkuttu. (5 x 4 = 20 marks) Turn over 2 C 61200 III. Write short essays on any six of the following : 20 Date of Ramayana. 21 Content of Narayaneeya. 22 18 Parvas of Mahabharata. 23 Peculiarities of Champukavyas. 24 Musical instruments in Kutiyattam. 25 Works of Sankaracharya. 26 Difference between Chakyarkuttu and Nangiarkuttu. -

Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts Notice Inviting

Quotation No. 05 / 2016-17 IGNCA / SRC / 16.2 / 2016 (Vol. II) INDIRA GANDHI NATIONAL CENTRE FOR THE ARTS SOUTHERN REGIONAL CENTRE BENGALURU – 560 056, Phone: 080-23212320 Quotation No. 05 / 2016-17 Bengaluru, the 27th October, 2016 NOTICE INVITING QUOTATION FOR SUPPLY OF BOOKS TO IGNCA SRC Sealed quotations are invited from licensed book vendors/suppliers/publishers as per the details given below. 1. Annexure – (A) – General Undertaking 2. Annexure – (B) – Terms and Conditions 3. Annexure – (C) – List of Books Sl. No. Details Date & Time 1. Last date for submission of Quotation 15.11.2016 till3:00 PM 2. Date of opening of Quotations 16.11.2016 at 3:00 PM Page 1 of 4 Quotation No. 05 / 2016-17 Annexure-A GENERAL UNDERTAKING Bengaluru, the 27th October, 2016 QUOTATION FOR SUPPLY OF BOOKS TO IGNCA SRC Sl. No. Particular Details 1. Name of the Firm with full Address 2. PAN No. (Copy of the PAN should be attached) 3. Telephone / Mobile No. 4. E-mail ID The terms & conditions of the quotation (Annexure-B) are acceptable to me/us Authorized Signatory (With full name, designation and Seal) Page 2 of 4 Quotation No. 05 / 2016-17 IGNCA / SRC / 16.2 / 2016 (Vol. II) INDIRA GANDHI NATIONAL CENTRE FOR THE ARTS SOUTHERN REGIONAL CENTRE BENGALURU – 560 056, Phone: 080-23212320 Annexure-B Terms & Conditions for Book Supply to IGNCA SRC: 1. The supplier should have a valid Trade License (Copy should be enclosed with CST, PAN, etc.). 2. Books should be supplied at a discount rate of Minimum 20%. -

The Music Academy, Madras 115-E, Mowbray’S Road

THE JOURNAL THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC VoLXXIX 1958 Parts I-1V silt si i m iiwfer m farmfo u “ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, nor in the Sun; where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada ! ” EDITED BY V. RAGHAVAN, m .a ., p h .d . 1959 PUBLISHED BY THE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD. MADRAS-14 Annual Subscription :—Inland Rs. 4 : Foreign 8 sh. Post paid. A11 correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editqr,Journal of the Music Academy. * Articles on musical Subjects,are accepted for publication; on the understandihg that they .are contributed solely to the Journal of the Music Academy. • n All’manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably typewrit ten (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and should be signed by the writer giving his address in full. ^ All .articles and communications intended for publication should reach the office at least one month before the date of publication (ordinarily the 15th of the* 1st month in each quarter). n The Editor of the. Journal is not responsible for the views expres sed by individual contributors. v All advertisements intended for publication should, reach the office not later than the 1st of the first month of each quarter. All books, moneys and cheques due to and intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editor. *• f ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES COV&R PA G ES: Full Page Half page A.• f Back (outside) Rs. -

Kerala History Timeline

Kerala History Timeline AD 1805 Death of Pazhassi Raja 52 St. Thomas Mission to Kerala 1809 Kundara Proclamation of Velu Thampi 68 Jews migrated to Kerala. 1809 Velu Thampi commits suicide. 630 Huang Tsang in Kerala. 1812 Kurichiya revolt against the British. 788 Birth of Sankaracharya. 1831 First census taken in Travancore 820 Death of Sankaracharya. 1834 English education started by 825 Beginning of Malayalam Era. Swatithirunal in Travancore. 851 Sulaiman in Kerala. 1847 Rajyasamacharam the first newspaper 1292 Italiyan Traveller Marcopolo reached in Malayalam, published. Kerala. 1855 Birth of Sree Narayana Guru. 1295 Kozhikode city was established 1865 Pandarappatta Proclamation 1342-1347 African traveller Ibanbatuta reached 1891 The first Legislative Assembly in Kerala. Travancore formed. Malayali Memorial 1440 Nicholo Conti in Kerala. 1895-96 Ezhava Memorial 1498 Vascoda Gama reaches Calicut. 1904 Sreemulam Praja Sabha was established. 1504 War of Cranganore (Kodungallor) be- 1920 Gandhiji's first visit to Kerala. tween Cochin and Kozhikode. 1920-21 Malabar Rebellion. 1505 First Portuguese Viceroy De Almeda 1921 First All Kerala Congress Political reached Kochi. Meeting was held at Ottapalam, under 1510 War between the Portuguese and the the leadership of T. Prakasam. Zamorin at Kozhikode. 1924 Vaikom Satyagraha 1573 Printing Press started functioning in 1928 Death of Sree Narayana Guru. Kochi and Vypinkotta. 1930 Salt Satyagraha 1599 Udayamperoor Sunahadhos. 1931 Guruvayur Satyagraha 1616 Captain Keeling reached Kerala. 1932 Nivarthana Agitation 1663 Capture of Kochi by the Dutch. 1934 Split in the congress. Rise of the Leftists 1694 Thalassery Factory established. and Rightists. 1695 Anjengo (Anchu Thengu) Factory 1935 Sri P. Krishna Pillai and Sri. -

Contribution of Kerala to Sanskrit Literature

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION B.A. SANSKRIT (2011 Admission) II SEMESTER COMPLEMENTARY COURSE CONTRIBUTION OF KERALA TO SANSKRIT LITERATURE QUESTION BANK 1.Who is the author of Mukundamala? a)Kulasekhara, b)Raghavananda, c)Lilasuka d)Kulasekhara Alwar 2.Which is the native place of Kulasekhara Alwar? a)Trichur, b)Cochin, c)Calicut, d)Thiruvanchikkulam 3.What is the name of the Tamil work written by Kulasekhara Alwar? a)Perumaltirumozhi, b)Akanannuru, c)Puranannuru, d)Cilappatikaram 4.Who is the famous commentator of Mukundamala? a)Narayanabhatta, b)Raghavananda, c)Krisnananda, d)Tolan 5.What is name of the commentary of Mukundamala written by Raghavananda? a)Prakasika b)Dipika c)Tatparyadipika d)Arthaprakasika Contribution of Kerala to Sanskrit Literature Page: 1 6.Who is the author of Krisnapadi commentary of Bhagavata? a)Ramavarman b)Vasudeva c) Raghavananda, d)Kulasekhara, 7.Who is the earliest commentator of Visnubhujanga of Sankara? a)Padmapada b)Lilasuka c) Raghavananda d)Nilakantha 8.Who is the guru of Raghavananda? a)Sankara b)Vilvamangala c) Krisnananda d)Nityamrtayati 9.Who is the author of Tapatisamvarana? a)Kulasekhara b)Saktibhadra c) Kulasekhara Alwar d)Narayanabhatta 10.Who is the author of Subhadradhananjaya? a)Raghavananda b)Vasudeva c) Narayanabhatta d)Kulasekhara 11.What is the prose work of Kulasekhara? a)Kadambari b)Tilakamanjari c) Ascaryamanjari d)Rasamanjari 12.Which was the capital city of KulasekharaVarman? a)Mahodayapuram b)Calicut c)Trivandrum d)Thrissur 13.What is the modern name of Mahodayapuram? -

Krishnattam in the Twenty-First Century1

ASIATIC, VOLUME 11, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2017 Circumscribed by Space and Time: An Assessment of the Popularity and Impact of Traditional Dance-drama Krishnattam in the Twenty-first Century1 Maya Vinai2 and M.G. Prasuna3 Birla Institute of Technology and Science-Pilani, Hyderabad Campus, India Article Received: 15 May 2017 Article Accepted: 30 October 2017 Abstract Temple art forms in South India form a unique site for conglomeration of art, culture, historicity and belief systems, and are indicative of the underlying social reality. Kerala, the southernmost tip of India, is perhaps one of the very few states where 2000-year old Sanskrit dramas are still performed in a conventional manner within the premises of the temple. Krishnattam, a form of dance-drama which depicts the journey of Lord Krishna in eight stages from avataram (birth of Lord Krishna) to swargarohanam (renouncement of the human form), is performed in temples like Guruvayoor. Despite all the technological advancements in and around the temple premises, Krishnattam has maintained its sanctity and authenticity, from the musical instruments played to the selection of artists for the performance. People still throng to book a performance of Krishnattam six months in advance. Our area of focus in the Krishnattam performance is the spell and impact it creates amongst the audience who are not performance critics, literary critics or aesthetic theorists – the majority of them being simply devotees or pilgrims who come to visit the temple. Our argument here is that the popularity of Krishnattam lies not just in the fact that it occupies a sacred space in the public imagination due to its undiluted ritualistic mores and highly stylised dance techniques but also due to the recuperative impact it has on the audience witnessing various episodes like avataram, rasakreeda, kaliyamardhanam or swayamvaram. -

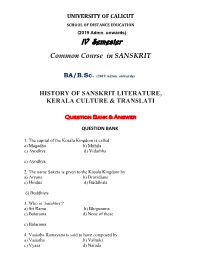

IV Semester Common Course in SANSKRIT

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION (2019 Admn. onwards) IV Semester Common Course in SANSKRIT BA/B.Sc. (2019 Admn. onwards) HISTORY OF SANSKRIT LITERATURE, KERALA CULTURE & TRANSLATI Question Bank & Answer QUESTION BANK 1. The capital of the Kosala Kingdom is called a) Magadha b) Mithila c) Ayodhya d) Vidarbha c) Ayodhya 2. The name Saketa is given to the Kosala Kingdom by a) Aryans b) Dravidians c) Hindus d) Buddhists d) Buddhists 3. Who is ‘halabhrt’? a) Sri Rama b) Bhrgurama c) Balarama d) None of these c) Balarama 4. Vasistha Ramayana is said to have composed by a) Vasistha b) Valmiki c) Vyasa d) Narada School of Distance Education b) Valmiki 5. Adhyatma Ramayana is an extract from a) Visnu Purana b) Brahmanda Purana c) Agni Purana d) Matsya Purana . b) Brahmandapurana 6. Mula Ramayana describes the importance of a) Rama b) Sita c) Ravana d) Hanuman . d) Hanuman 7. The most well known commentary on the Ramayana is a) Valmiki Ramayana b) Bhusanam c) Dharmakuta d) Ramayananvayi b) Bhusanam 8. Ramayanadipika is written by a) Maheswaratirtha b) Vidyanatha Diksita c) Hari Pandita d) Nagesa b) Vidyanatha Dikshita 9. Valmikihrdayam is a commentary on the Ramayana written by a) Ahobala b) Govindaraja . a) Ahobala 10. ………….. is a splendid critique on the Ramayana. a) Dharmakutam b) Ramayanabhusanam c) Tirthiyam d) None of these . a) Dharmakutam 11. The author of Dharmakutam is a) Tryambaka Makhin b) Gangadhara c) Nrsimha d) Venkatacarya . a) Tryambaka Makhin History of Sanskrit Literature, Kerala Culture & Translation Page 2 School of Distance Education 12. How many verses are there in the Ramayana? a) 24,000 b) 25,000 c) 1, 00,000 d) 22,000 . -

Promotion of Traditional Theatre Arts: the Role of the Incumbents 42

2 THE PROMOTON OF TRADITIONAL THEATRE ARTS: PROBLEMS AND POSSIBIL ITIES Submitted to Kerala Research Program of Local Level Development Centre for Development Studies Uloor Thiruvananthapuram Submitted by DR JOSE GEORGE Dept./Research Centre in English Mar Athanasius College Kothamangalam Ernakulam. 4 January 2002 3 CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Preface 5 Abstract 6 Chapter I Introduction: When Market Forces Overrules Classical Theatre Genres 9 II From Feudal Historicity to Institutional Maneuvering 17 III Ethnographic RealityCheck: Interplay of Cultural Ideology Versus Image Politics 33 IV The Promotion of Traditional Theatre Arts: The Role of the Incumbents 42 V Conclusion 56 Appendix 61 Select Bibliography 64 4 Acknowledgements Our acknowledgements due to numerous persons and institutions who helped to formulate the ideas and suggestions of this project. We are sincerely thankful to all of them. Our special thanks to Dr K Narayanan Nair, Co-Ordinator of Kerala Research Program of Local Level Development and his associates for funding this project and all other encouragements. The secretary, principal, staff and students of Kerala Kalamandalam; Persons of the Ammannur Gurukulam, Krishnanattam Kaliyogam of Guruvayoor, Sangeet Natak Akademy, Margi, Sanskrit University, various Kathakali clubs; freelance artists et al deserve special thanks. Some of the individuals who deserve special thanks are: NPS Namboodiri, LS Rajagopal, NP Unni, KG Paulose, P Rama Iyer, P Venugopal, VR Prabodhachandran Nayar, Ayyappapanikker, Kavalam Narayana Panikker, VKB Nambiar, G Venu, Margi Madhu, Usha Nangiar, Margi Narayanan, Kalamandalam Krishnakumar, Silpi Jenardhanan, Ramesh Varma, Sati Varma, P Appukkuttan, N Radhakrishnan Nair and others who helped us by filling the questionnaire. We are very thankful to all of them.