Themes of Kathakali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Academic Catalog 2020

Academic Catalog 03/01/2020 – 12/31/2020 University of Silicon Andhra Dr. Hanimireddy Lakireddy Bhavan 1521 California Circle, Milpitas, CA 95035 1-844-872-8680 www.universityofsiliconandhra.org University of Silicon Andhra, Academic Catalog- 2020 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION: ............................................................................................ 5 Mission Statement ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Vision Statement ..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Institutional Learning Outcomes ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Notice to Current and Prospective Students ......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Academic Freedom Statement .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Notice to Prospective Degree Program Students -

8. Krishna Karnamrutam

Sincere Thanks To: 1. SrI nrusimha SEva rasikan, Oppiliappan Koil V.SaThakOpan swAmi, Editor- In-Chief of sundarasimham-ahobilavalli kaimkaryam for kindly editing and hosting this title in his eBooks series. 2. Mannargudi Sri.Srinivasan NarayaNan swami for compilation of the source document and providing Sanskrit/Tamil Texts and proof reading 3. The website http://www.vishvarupa.com for providing the cover picture of Sri GuruvAyUrappan 4. Nedumtheru Sri.Mukund Srinivasan,Sri.Lakshminarasimhan Sridhar, www.sadagopan.org www.sadagopan.org Smt.Krishnapriya for providing images. 5. Smt.Krishnapriya for providing the biography of Sri Leela Sukhar for the appendix section and 6. Smt. Jayashree Muralidharan for eBook assembly C O N T E N T S Introduction 1 Slokams and Commentaries 3 Slokam 1 -10 5-25 Slokam 11 - 20 26-44 Slokam 21 - 30 47-67 Slokam 31 - 40 69-84 www.sadagopan.org www.sadagopan.org Slokam 41 - 50 86-101 Slokam 51 - 60 103-119 Slokam 61 - 70 121-137 Slokam 71 - 80 141-153 Slokam 81 - 90 154-169 Slokam 91 - 100 170-183 Slokam 101 - 110 184-201 nigamanam 201 Appendix 203 Brief Biography of Sri Leelaa Sukhar 205 Complete List of Sundarasimham-ahobilavalli eBooks 207 www.sadagopan.org www.sadagopan.org SrI GuruvAyUrappan . ïI>. ïIlIlazukkiv ivrictm! . ïIk«:[k[aRm&tm!. KRISHNAAKARNAAMRTAM OF LEELASUKA X×W www.sadagopan.org ABOUT THE AUTHOR The name of the author of this slokam is Bilavamangala and he acquired the name Leelasuka because of his becoming immersed in the leela of KrishNa and describing it in detail like Sukabrahmarshi. -

Krishnanattam- Glances Across the Screen an Analysis of the Divine Dance Drama Under the Rubric of Cultural Economics

2017/2364 (3) 211 IF : 4.176 | IC Value : 78.46 VOL- (3) ISSUE 211 ISSN 2017/2364 Culture KRISHNANATTAM- GLANCES ACROSS THE SCREEN AN ANALYSIS OF THE DIVINE DANCE DRAMA UNDER THE RUBRIC OF CULTURAL ECONOMICS Prof.K X Joseph || Department of Economics University of Calicut Dr John Mathai Centre Aranattukara Thrissur. Kerala has a composite and cosmopolitan culture which was the contribution of several people and races. When we analyse the cultural history of Kerala we can see the importance of temple art forms. These art forms cater the entertainment of upper castes, mainly Brahmins and Kshatriyas. Kuthu , Krishnanattam, Kathakali and Koodiyattam were the products of this culture. This cultural phenomenon reflects the style of life of the people and it also affects the ‘economic culture’ of the people of Kerala. Krishnanattam- Glances across ,the screen An analysis, of the Divine Divine Dance, Drama under ,the Rubric ,of Cultural Economics. INTRODUCTION on eight successive nights. On the ninth day ‘Avatharam’ was to be presented again and to end the series auspiciously. The importance of this art form in Guruvayoor temple has been attributed to the fact that, it is considered as a prime form of offering Krishnanattam under the rubric of Cultural Economics: by the devotees to the ‘God Krishna’ for the fulfillment of their As Du Mount states, there is a definite relationship between caste and wishes. Krishnanattam, though it owes its origin to ‘Koodi- yattam’, occupation, eventually contributed to the stability of caste system the earliest art form of the dance drama traditions of Kerala, is which is a major hazard in the way of social mobility. -

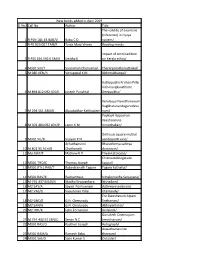

April 2019 Sl.No

New books added in April 2019 Sl.No. Call No. Author Title The validity of anumana (inference) in nyaya 1 R PSN 181.43 BAB/V Babu C D system/ 2 R PE 823.007 TAN/R Tania Mary Vivera Reading minds: Impact of smrti tadition 3 R PSS 294.592 6 SMI/I Smitha K on Kerala ethos/ 4 M301 SIV/T Sivaraman Cheriyanad Theranjedutha kathakal/ 5 M 080 VEN/A Venugopal K M Abhimukhangal/ Kuttippuzha Krishan Pillai Vicharaviplavathinte 6 M 894.812 092 JOS/K Joseph Panakkal Deepasikha/ Keraleeya Navothanavum Vagbhatanandagurudeva 7 M 294.561 ABO/K Aboobakkar Kathiyalam num/ Poykayil Appachan Keezhalarute 8 M 303.484 092 LEN/P Lenin K M Vimochakan/ Delhousi square muthal 9 M301 VIJ/D Vijayan P N aandippatti vare/ Achuthanunni Bharatheeya sahitya 10 M 801.95 ACH/B Chathanath darsanam/ 11 M3 MAT/T Mathew K P Theekkattiloote/ Chitrasalabhagalude 12 M301 THO/C Thomas Joseph kappal/ 13 M301 (ITr.) RAB/T Rabindranath Tagore Tagore kathakal/ 14 M301 RAV/K Ravivarma p Kimakurvatha Sanjayana/ 15 M 791.437 MAD/N Madhu Ervavankara Nishadam/ 16 M2 SAY/A Sayed Ponkunnam Aathmanivedanam/ 17 M2 VAS/U Vasudevan Pillai Utampady/ Ere Dweshavum Alpam 18 M2 GNC/E G.N. Cheruvadu Snehavum/ 19 M2 SAN/A G.N. Cheruvadu Abhayarthikal/ 20 M2 JOH/K John Fernandaz Kollakolli/ Gurudeth Cinemayum 21 M 791.430 92 SEN/G Senan N C Jeevithavum/ 22 M301 KAS/O Kasthuri Joseph Autograph/ Aswathamavinte 23 M301 RAM/A Ramesh Babu theeram/ 24 M301 SAJ/O Sajiv Kumar S Outsider/ 25 M301 VEN/A Venugopalan T P Anunasikam/ Jayasankaran Kunjikrishnanmesiri 26 M301 JAY/K Puthuppalli vivahithanayi/ 27 M3 -

Chapter Iv Traces of Historical Facts From

CHAPTER IV TRACES OF HISTORICAL FACTS FROM SANDESAKAVYAS & SHORT POEMS Sandesakavyas occupy an eminent place among the lyrics in Sanskrit literature. Though Valmiki paved the way in the initial stage it was Kalidasa who developed it into a perfect form of poetic literature. Meghasandesa, the unique work of Kalidasa, was re- ceived with such enthusiasam that attempts were made to emulate it all over India. As result there arose a significant branch of lyric literature in Sanskrit. Kerala it perhaps the only region which produced numerous works of real merit in this field. The literature of Kerala is full of poems of the Sandesa type. Literature can be made use of to yield information about the social history of a land and is often one of the main sources for reconstructing the ancient social customs and manners of the respective periods. History as a separate study has not been seriously treated in Sanskrit literature. Apart form literary merits, the Sanskrit literature of Kerala contains several historical accounts of the country with the exception of a few historical Kavyas, it is the Sandesakavyas that give us some historical details. Among the Sanskrit works, the Sandesa Kavya branch stands in a better position in this field (matter)Since it contains a good deal of historical materials through the description of the routes to be followed by the messengers in the Sandesakavyas. The Sandesakavyas play an impor- tant role in depicting the social history of their ages. The keralate Sandesakavyas are noteworthy because of the geographical, historical, social and cultural information they supply about the land. -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Thiruporur Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 01/11/2020 01/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 01/11/2020 AMUTHA PRABAKARAN (H) DOOR NO 2/70, INDIRA GANDHI STREET, KARANAI- VILLAGE,CHENNAI, , 2 01/11/2020 Kishore Kumar Thakur Indra Kant Thakur (F) Flat No. D02 303, Provident Cosmo City 41 Dr Abdul Kalam Road, Pudupakkam, , 3 01/11/2020 VIMALRAJ E ELUMALAI (F) 3/327, CSI SCHOOL STREET, KAYAR, , 4 01/11/2020 JAYARAMAN V VENKATESAN 113, bigstreet, NATHAM VENKATESAN M VENKATESAN (F) ,NATHAM KARIYACHERI, , £ In case of Union territories having no Legislative Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir Date of exhibition at @ For this revision for this designated location designated location under Date of exhibition at Electoral * Place, time and date of hearings as fixed by electoral registration officer rule 15(b) Registration Officer¶s Office under $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each designated rule 16(b) location # Give relationship as F-Father, M=Mother, and H=Husband within brackets i.e. (F), (M), (H) 17/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Thiruporur Revision identity applications have been received) 1. -

An Introduction to The-History of Music Amongst

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE-HISTORY OF MUSIC AMONGST INDIAN SOUTH AFRICANS IN NATAL 1860-1948: 10WARDS MEL VEEN BETH J ACf::::'GN DURBAN JANUARY 1988 Of ~he hi stoczf ffiCISi C and mic and so; -political status Natal, 186<)- 1948. The study conce ns itself e:-:pr- essi on of musi c and the meanings associated with it. Music for-ms, music per-sonalities, and music functions ar-e tr-aced. Some expl anations of the rel a tionships between cl ass str-uctur-es, r- eligious expr-ession, political affiliation, and music ar-e suggested. The first chapter establishes the topic, par-ameters, motivation, pur-pose, theor-etical framewor-k, r esear-ch method and cons traints of the study. The main findings ar-e divided between two chronological sections, 1860-1920 and 1920-1948. The second chapter- describes early political and social structures, the South African phase of Gandhi's satyagraha, Muslim/Hindu festivals, early Christian activity, e arly organisation of a South Indian Hindu music group, the beginnings of the Lawrence family, and the sparking of interest in classical Indian music. The third chapter indicates the changing nature of occupation and life-style f rom a rural to an how music styles changed to suit t he new, Assimilation, assimilation music:: Ind :i. dn Ei s_ fo~ s.. Hindu an·I Muslim.. are identified. including both imported recorcl recor· / and the growth of the cl assi -al music movement ar-e traced, and the role of the "Indian II or-chestr·a is anal yst~d . Chapter· four presents the main conclusions, regarding the cultural, political, and social disposition of Indi a n South Africans, educational implications, and s ome areas requiring further research. -

MA Syllbus 2014 Revised 17 8 14

SYLLABUS FOR M.A. PROGRAMME IN SANSKRIT SAHITYA (2014 June onwards) The syllabus of M.A. programme in Sanskrit Sahitya (Course Credit and Semester System) is being restructured in order to satisfy the contemporary requirements on the basis of the recent developments in the academic field. To provide an interdisciplinary nature to the courses, some areas of studies are developed, changed and/or redefined. M.A. programme is consisted of four semesters. Total number of courses is 20. Each course is having 4 credits. Thus the student has to acquire a minimum total of 80 credits for completing the programme. Among the 20 courses of the PG programme, 7 are electives/optionals out of which 5 should be from the parent department(Internal Electives) and the remaining two must be, from any other departments(multidisciplinary electives). There will be five courses in each semester and five hours are distributred for each course. There will be 3 core courses and two elective/optional course in each semester. In the first and fourth semesters, elective/optional courses are to be taken from within the parent department from the internal electives given in the list and in the second and third, it has to be from other departments. Students of other departments can opt the multidisciplinary elective courses offerd by the Department of Sanskrit Sahitya in the second and third semesters and the students may write answers either in Sanskrit, or in English or in Malayalam The Course 20, ie, ProjectCourse No:1 (Dissertation) will be in the form of the presentation of seminar and a project work done by each and every student. -

C 61200 (Pages : 2)� Name � Reg

C 61200 (Pages : 2) Name Reg. No FOURTH SEMESTER B.A./B.Sc. DEGREE EXAMINATION APRIL 2019 (CUCBCSS—UG) Sanskrit SKT 4A 10—HISTORY OF SANSKRIT LITERATURE, KERALA CULTURE AND TRANSLATION Time ; Three Hours Maximum : 80 Marks Answers may be written either in Sanskrit or in English or in Malayalam. In writing Sanskrit, Devanagari script should be used. I. Answer any ten in one or two words : 1 Who is known as Adikavi ? 2 What does the term "Panivada" indicate ? 3 Who is the author of Raghunathanbhyudaya ? 4 Which temple art form is enacted only by women ? Fill in the blanks with suitable words : 5 is the longest poem ever known in literary history. 6 There are kandas in Ramayana. 7 Narayanabhatta represented school of Mimamsa. 8 Kutiyattam is performed at specially built Temple theatres known as Answer in one word : 9 Which text is composed by Manaveda for Krishnanattam ? .10 Who is the author of Darsanamala ? 11 Name the historical poem written by A.R. Rajaraja Varma ? 12 Mention the art form in which humour is of much importance ? (10 x 1 = 10 marks) II. Write short notes on any five of the following : 13 Valmiki. 14 Rajatarangini. 15 Bharatachampu. 16 Sree Narayana Guru. 17 Yasastilaka Champu. 18 Punnasseri Nambi. 19 Chakyarkuttu. (5 x 4 = 20 marks) Turn over 2 C 61200 III. Write short essays on any six of the following : 20 Date of Ramayana. 21 Content of Narayaneeya. 22 18 Parvas of Mahabharata. 23 Peculiarities of Champukavyas. 24 Musical instruments in Kutiyattam. 25 Works of Sankaracharya. 26 Difference between Chakyarkuttu and Nangiarkuttu. -

Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts Notice Inviting

Quotation No. 05 / 2016-17 IGNCA / SRC / 16.2 / 2016 (Vol. II) INDIRA GANDHI NATIONAL CENTRE FOR THE ARTS SOUTHERN REGIONAL CENTRE BENGALURU – 560 056, Phone: 080-23212320 Quotation No. 05 / 2016-17 Bengaluru, the 27th October, 2016 NOTICE INVITING QUOTATION FOR SUPPLY OF BOOKS TO IGNCA SRC Sealed quotations are invited from licensed book vendors/suppliers/publishers as per the details given below. 1. Annexure – (A) – General Undertaking 2. Annexure – (B) – Terms and Conditions 3. Annexure – (C) – List of Books Sl. No. Details Date & Time 1. Last date for submission of Quotation 15.11.2016 till3:00 PM 2. Date of opening of Quotations 16.11.2016 at 3:00 PM Page 1 of 4 Quotation No. 05 / 2016-17 Annexure-A GENERAL UNDERTAKING Bengaluru, the 27th October, 2016 QUOTATION FOR SUPPLY OF BOOKS TO IGNCA SRC Sl. No. Particular Details 1. Name of the Firm with full Address 2. PAN No. (Copy of the PAN should be attached) 3. Telephone / Mobile No. 4. E-mail ID The terms & conditions of the quotation (Annexure-B) are acceptable to me/us Authorized Signatory (With full name, designation and Seal) Page 2 of 4 Quotation No. 05 / 2016-17 IGNCA / SRC / 16.2 / 2016 (Vol. II) INDIRA GANDHI NATIONAL CENTRE FOR THE ARTS SOUTHERN REGIONAL CENTRE BENGALURU – 560 056, Phone: 080-23212320 Annexure-B Terms & Conditions for Book Supply to IGNCA SRC: 1. The supplier should have a valid Trade License (Copy should be enclosed with CST, PAN, etc.). 2. Books should be supplied at a discount rate of Minimum 20%. -

Malayalam - Novel

NEW BOMBAY KERALEEYA SAMAJ , LIBRARY LIBRARY LIST MALAYALAM - NOVEL SR.NO: BOOK'S NAME AUTHOR TYPE 4000 ORU SEETHAKOODY A.A.AZIS NOVEL 4001 AADYARATHRI NASHTAPETTAVAR A.D. RAJAN NOVEL 4002 AJYA HUTHI A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4003 UPACHAPAM A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4004 ABHILASHANGELEE VIDA A.P.I. SADIQ NOVEL 4005 GREEN CARD ABRAHAM THECKEMURY NOVEL 4006 TARSANUM IRUMBU MANUSHYARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4007 TARSANUM KOLLAKKARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4008 PATHIMOONNU PRASNANGAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4009 ABC NARAHATHYAKAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4010 HARITHABHAKALKK APPURAM AKBAR KAKKATTIL NOVEL 4011 ENMAKAJE AMBIKA SUDAN MANGAD NOVEL 4012 EZHUTHATHA KADALAS AMRITA PRITAM NOVEL 4013 MARANA CERTIFICATE ANAND NOVEL 4014 AALKKOOTTAM ANAND NOVEL 4015 ABHAYARTHIKAL ANAND NOVEL 4016 MARUBHOOMIKAL UNDAKUNNATHU ANAND NOVEL 4017 MANGALAM RAHIM MUGATHALA NOVEL 4018 VARDHAKYAM ENDE DUKHAM ARAVINDAN PERAMANGALAM NOVEL 4019 CHORAKKALAM SIR ARTHAR KONAN DOYLE D.NOVEL 4020 THIRICHU VARAVU ASHTAMOORTHY NOVEL 4021 MALSARAM ASHWATHI NOVEL 4022 OTTAPETTAVARUDEY RATHRI BABU KILIROOR NOVEL 4023 THANAL BALAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4024 NINGAL ARIYUNNATHINE BALAKRISHNAN MANGAD NOVEL 4025 KADAMBARI BANABATTAN NOVEL 4026 ANANDAMADAM BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJI NOVEL 4027 MATHILUKAL VIKAM MOHAMMAD BASHEER NOVEL 4028 ATTACK BATTEN BOSE NOVEL 4029 DR.DEVIL BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4030 CHANAKYAPURI BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4031 RAKTHA RAKSHASSE BRAM STOCKER NOVEL 4032 NASHTAPETTAVARUDEY SANGAGANAM C.GOPINATH NOVEL 4033 PRAKRTHI NIYAMAM C.R.PARAMESHWARAN NOVEL 4034 CHUZHALI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4035 VERUKAL PADARUNNA VAZHIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4036 ATHIRUKAL KADAKKUNNAVAR C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4037 SAHADHARMINI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4038 KAANAL THULLIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4039 POOJYAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4040 KANGALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4041 THEVADISHI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4042 KANKALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4043 MRINALAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4044 KANNIMANGAKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4045 MALAKAMAAR CHIRAKU VEESHUMBOL C.V. -

The Music Academy, Madras 115-E, Mowbray’S Road

THE JOURNAL THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC VoLXXIX 1958 Parts I-1V silt si i m iiwfer m farmfo u “ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, nor in the Sun; where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada ! ” EDITED BY V. RAGHAVAN, m .a ., p h .d . 1959 PUBLISHED BY THE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD. MADRAS-14 Annual Subscription :—Inland Rs. 4 : Foreign 8 sh. Post paid. A11 correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editqr,Journal of the Music Academy. * Articles on musical Subjects,are accepted for publication; on the understandihg that they .are contributed solely to the Journal of the Music Academy. • n All’manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably typewrit ten (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and should be signed by the writer giving his address in full. ^ All .articles and communications intended for publication should reach the office at least one month before the date of publication (ordinarily the 15th of the* 1st month in each quarter). n The Editor of the. Journal is not responsible for the views expres sed by individual contributors. v All advertisements intended for publication should, reach the office not later than the 1st of the first month of each quarter. All books, moneys and cheques due to and intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editor. *• f ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES COV&R PA G ES: Full Page Half page A.• f Back (outside) Rs.