An Introduction to The-History of Music Amongst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mid Wales Llanidloes

This document is a snapshot of content from a discontinued BBC website, originally published between 2002-2011. It has been made available for archival & research purposes only. Please see the foot of this document for Archive Terms of Use. 4 May 2012 Accessibility help Text only BBC Homepage Wales Home Archer's Actor - Jamila Massey more from this section Last updated: 03 August 2006 Llanidloes The actor Jamila Massey is Archer's Actor - Jamila Massey Chartist Revolt famous for her role as Auntie Claims to Fame Satya in Radio 4 's daily Clywedog Dam Clywedog Sailing Club BBC Local agricultural sopa opera the Archers. She has lived in Going Solar Mid Wales Great Outdoors Festival 2007 Llanidloes for nearly twenty Things to do Info Centres years. Read on to find out Llani Car Club People & Places more about her life and work. Llanidloes Museum Nature & Outdoors My Town History Outside Looking In Phototour Religion & Ethics How did you get into acting? Rotary Across Wales Walk Arts & Culture Sport Centre Fun Day Music I came to the UK with my parents in 1946. After the war, my Timber-Framed Buildings TV & Radio father didn't want to be in the army anymore and he applied to the BBC and got a producer's job at 200 Oxford Street. Local BBC Sites The studios were later moved to Bush House. He was that News rare commodity - a born broadcaster - and, I suspect, some Sport of that rubbed off on to me. Weather Travel At that time, there were few Asians in this country and Neighbouring Sites certainly very few Asian children. -

Academic Catalog 2020

Academic Catalog 03/01/2020 – 12/31/2020 University of Silicon Andhra Dr. Hanimireddy Lakireddy Bhavan 1521 California Circle, Milpitas, CA 95035 1-844-872-8680 www.universityofsiliconandhra.org University of Silicon Andhra, Academic Catalog- 2020 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION: ............................................................................................ 5 Mission Statement ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Vision Statement ..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Institutional Learning Outcomes ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Notice to Current and Prospective Students ......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Academic Freedom Statement .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Notice to Prospective Degree Program Students -

Hindu Music from Various Authors, Pom.Pil.Ed and J^Ublished

' ' : '.."-","' i / i : .: \ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY MUSIC e VerSl,y Ubrary ML 338.fl2 i882 3 1924 022 411 650 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 92402241 1 650 " HINDU MUSIC FROM VARIOUS AUTHORS, POM.PIL.ED AND J^UBLISHED RAJAH COMM. SOURINDRO MOHUN TAGORE, MUS. DOC.J F.R.S.L., M.U.A.S., Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire ; KNIGHT COMMANDER OF THE FIRST CLASS OF THE ORDER OF ALBERT, SAXONY ; OF THE ORDER OF LEOPOLD, BELGIUM ; FRANCIS OF THE MOST EXALTED ORDEE OF JOSEPH, AUSTRIA ; OF THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE CROWN OF ITALY ; OF THE MOST DISTINGUISHED ORDER OF DANNEBROG, DENMARK ; AND OF THE ROYAL ORDER OF MELTJSINE OF PRINCESS MARY OF LUSIGNAN ; FRANC CHEVALIER OF THE ORDER OF THE KNIGHTS OF THE MONT-REAL, JERUSALEM, RHODES HOLY SAVIOUR OF AND MALTA ; COMMANDEUR DE ORDRE RELIGIEOX ET MILITAIRE DE SAINT-SAUVEUR DE MONT-REAL, DE SAINT-JEAN DE JERUSALEM, TEMPLE, SAINT SEPULCRE, DE RHODES ET MALTE DU DU REFORME ; KNIGHT OF THE FIRST CLASS OF THE IMPERIAL ORDER OF THE " PAOU SING," OR PRECIOUS STAR, CHINA ; OF THE SECOND CLASS OF THE HIGH IMPERIAL ORDER OF THE LION AND SUN, PERSIA; OF THE SECOND CLASS OF THE IMPERIAL ORDER OF MEDJIDIE, TURKEY ; OF THE ROYAL MILITARY ORDER OF CHRIST, AND PORTUGAL ; KNIGHT THE OF BASABAMALA, OF ORDER SIAM ; AND OF THE GURKHA STAR, NEPAL ; " NAWAB SHAHZADA FROM THE SHAH OF PERSIA, &C, &C, &C. -

Ym Mis Mai 2010 Dathlwyd Pedwaredd Flwyddyn

o bobl wedi cyfranogi, neu wedi mynychu digwyddiadau Gwanwyn, a drefnwyd gan 92 o grwpiau cymunedol a mudiadau. Mae hyn yn cynrychioli cynnydd o 10% mewn cyfranogiad ers 2009, wedi’i fynegi o ran y mudiadau a gyfranogodd, a chynnydd o 14% amcangyfrifol wedi’i fynegi o ran cyfranogwyr • crëwyd cyfleoedd ar gyfer grwpiau a mudiadau sy’n ymwneud â cherddoriaeth, dawns, celf, ysgrifennu a disgyblaethau artistig arall, i arddangos neu i berfformio eu gwaith a chymell 2010 aelodau newydd i gyfranogi • codwyd proffil Gŵyl Gwanwyn ymhellach ar Cyflwyniad draws Cymru. Derbyniodd gŵyl Gwanwyn sylw ffafriol yn ‘Ychwanegu Bywyd at Flynyddoedd Ym mis Mai 2010 dathlwyd – Ymagweddau Cymreig at Bolisi Heneiddio’ a pedwaredd flwyddyn Gŵyl Gwanwyn: gyhoeddwyd gan y Sefydliad Materion Cymreig. Gŵyl y Celfyddydau a Chreadigrwydd Hefyd, dyfynnwyd bod yr ŵyl yn enghraifft batrymol yn adroddiad ‘Ageing Artfully’ a ar gyfer Pobl Hŷn a gyd-drefnir gan gyhoeddwyd gan Sefydliad Baring Age Cymru. • mae cydberthnasau’n datblygu gyda nifer o fudiadau a lleoliadau’r celfyddydau, yn Wedi i fwy o nawdd i gael ei neilltuo ar ei chyfer genedlaethol ac yn rhanbarthol, sy’n awyddus oddi wrth Lywodraeth Cynulliad Cymru (LlCC) a i fod yn rhan o’r ŵyl yn 2011 a thu hwnt. Chyngor Celfyddydau Cymru (CCC), bu’n bosib Datblygwyd perthynas dda yn arbennig gyda i’r ŵyl i ddilyn ei nod o hyrwyddo manteision Gŵyl Lenyddiaeth y Gelli, o ganlyniad i lansio’r iechyd a lles i bobl hŷn, trwy gyfranogi mewn detholiad ‘Aged to Perfection’, ac mae perthynas gweithgareddau artistig a chreadigol i: waith debyg yn cael ei meithrin gyda Gŵyl • hyrwyddo digwyddiadau lleol ar draws Cymru i Gerdd Gregynog yng Nghanolbarth Cymru. -

Hindu Music in Bangkok: the Om Uma Devi Shiva Band

Volume 22, 2021 – Journal of Urban Culture Research Hindu Music In Bangkok: The Om Uma Devi Shiva Band Kumkom Pornprasit+ (Thailand) Abstract This research focuses on the Om Uma Devi Shiva, a Hindu band in Bangkok, which was founded by a group of acquainted Hindu Indian musicians living in Thailand. The band of seven musicians earns a living by performing ritual music in Bangkok and other provinces. Ram Kumar acts as the band’s manager, instructor and song composer. The instruments utilized in the band are the dholak drum, tabla drum, harmonium and cymbals. The members of Om Uma Devi Shiva band learned their musical knowledge from their ancestors along with music gurus in India. In order to pass on this knowledge to future generations they have set up music courses for both Indian and Thai youths. The Om Uma Devi Shiva band is an example of how to maintain and present one’s original cultural identity in a new social context. Keywords: Hindu Music, Om Uma Devi Shiva Band, Hindu Indian, Bangkok Music + Kumkom Pornprasit, Professor, Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. email: [email protected]. Received 6/3/21 – Revised 6/5/21 – Accepted 6/6/21 Volume 22, 2021 – Journal of Urban Culture Research Hindu Music In Bangkok… | 218 Introduction Bangkok is a metropolitan area in which people of different ethnic groups live together, weaving together their diverse ways of life. Hindu Indians, considered an important ethnic minority in Bangkok, came to settle in Bangkok during the late 18 century A.D. to early 19 century A.D. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

April 2019 Sl.No

New books added in April 2019 Sl.No. Call No. Author Title The validity of anumana (inference) in nyaya 1 R PSN 181.43 BAB/V Babu C D system/ 2 R PE 823.007 TAN/R Tania Mary Vivera Reading minds: Impact of smrti tadition 3 R PSS 294.592 6 SMI/I Smitha K on Kerala ethos/ 4 M301 SIV/T Sivaraman Cheriyanad Theranjedutha kathakal/ 5 M 080 VEN/A Venugopal K M Abhimukhangal/ Kuttippuzha Krishan Pillai Vicharaviplavathinte 6 M 894.812 092 JOS/K Joseph Panakkal Deepasikha/ Keraleeya Navothanavum Vagbhatanandagurudeva 7 M 294.561 ABO/K Aboobakkar Kathiyalam num/ Poykayil Appachan Keezhalarute 8 M 303.484 092 LEN/P Lenin K M Vimochakan/ Delhousi square muthal 9 M301 VIJ/D Vijayan P N aandippatti vare/ Achuthanunni Bharatheeya sahitya 10 M 801.95 ACH/B Chathanath darsanam/ 11 M3 MAT/T Mathew K P Theekkattiloote/ Chitrasalabhagalude 12 M301 THO/C Thomas Joseph kappal/ 13 M301 (ITr.) RAB/T Rabindranath Tagore Tagore kathakal/ 14 M301 RAV/K Ravivarma p Kimakurvatha Sanjayana/ 15 M 791.437 MAD/N Madhu Ervavankara Nishadam/ 16 M2 SAY/A Sayed Ponkunnam Aathmanivedanam/ 17 M2 VAS/U Vasudevan Pillai Utampady/ Ere Dweshavum Alpam 18 M2 GNC/E G.N. Cheruvadu Snehavum/ 19 M2 SAN/A G.N. Cheruvadu Abhayarthikal/ 20 M2 JOH/K John Fernandaz Kollakolli/ Gurudeth Cinemayum 21 M 791.430 92 SEN/G Senan N C Jeevithavum/ 22 M301 KAS/O Kasthuri Joseph Autograph/ Aswathamavinte 23 M301 RAM/A Ramesh Babu theeram/ 24 M301 SAJ/O Sajiv Kumar S Outsider/ 25 M301 VEN/A Venugopalan T P Anunasikam/ Jayasankaran Kunjikrishnanmesiri 26 M301 JAY/K Puthuppalli vivahithanayi/ 27 M3 -

Monstrous Aunties: the Rabelaisian Older Asian Woman in British Cinema and Television Comedy

Monstrous Aunties: The Rabelaisian older Asian woman in British cinema and television comedy Estella Tincknell, University of the West of England Introduction Representations of older women of South Asian heritage in British cinema and television are limited in number and frequently confined to non-prestigious genres such as soap opera. Too often, such depictions do little more than reiterate familiar stereotypes of the subordinate ‘Asian wife’ or stage the discursive tensions around female submission and male tyranny supposedly characteristic of subcontinent identities. Such marginalisation is compounded in the relative neglect of screen representations of Asian identities generally, and of female and older Asian experiences specifically, within the fields of Film and Media analysis. These representations have only recently begun to be explored in more nuanced ways that acknowledge the complexity of colonial and post-colonial discoursesi. The decoupling of the relationship between Asian and Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi heritage, together with the foregrounding of religious rather than national-colonial identities, has further rendered the topic more complex. Yet there is an exception to this tendency. In the 1990s, British comedy films and TV shows began to carve out a space in which transgressive representations of aging Asian women appeared. From the subversively mischievous Pushpa (Zohra Segal) in Gurinder Chadha’s debut feature, Bhaji on the Beach (1993), to the bickering ‘competitive mothers’ of the ground-breaking sketch show, Goodness, Gracious Me (BBC 1998 – 2001, 2015), together 1 with the sexually-fixated grandmother, Ummi (Meera Syal), in The Kumars at Number 42 (BBC, 2001-6; Sky, 2014), a range of comic older female figures have overturned conventional discourses. -

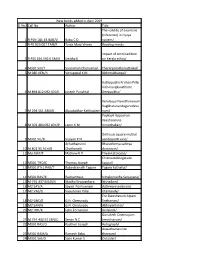

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Thiruporur Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 01/11/2020 01/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 01/11/2020 AMUTHA PRABAKARAN (H) DOOR NO 2/70, INDIRA GANDHI STREET, KARANAI- VILLAGE,CHENNAI, , 2 01/11/2020 Kishore Kumar Thakur Indra Kant Thakur (F) Flat No. D02 303, Provident Cosmo City 41 Dr Abdul Kalam Road, Pudupakkam, , 3 01/11/2020 VIMALRAJ E ELUMALAI (F) 3/327, CSI SCHOOL STREET, KAYAR, , 4 01/11/2020 JAYARAMAN V VENKATESAN 113, bigstreet, NATHAM VENKATESAN M VENKATESAN (F) ,NATHAM KARIYACHERI, , £ In case of Union territories having no Legislative Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir Date of exhibition at @ For this revision for this designated location designated location under Date of exhibition at Electoral * Place, time and date of hearings as fixed by electoral registration officer rule 15(b) Registration Officer¶s Office under $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each designated rule 16(b) location # Give relationship as F-Father, M=Mother, and H=Husband within brackets i.e. (F), (M), (H) 17/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Thiruporur Revision identity applications have been received) 1. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

The Sound of Belonging

The Sound of Belonging Music and Ethnic Identification among Marrons and Hindus in Paramaribo, Suriname Verena Brey Anne Goudzwaard Background picture: Hindu Dancer Small photograph: Marron Dance Group Both pictures were taken during a performance for festivities of the women's club “Soroptimist”, March 19th 2015. The Sound of Belonging Music and Ethnic Identification among Marrons and Hindus in Paramaribo, Suriname Verena Brey, 3920356 [email protected] Anne Goudzwaard 4028279 [email protected] Wordcount: 19192 Coordinator: Hans de Kruijf June 2015 Content 1.Introduction..............................................................................................................................9 2.Theoretical Frame..................................................................................................................13 2.1Ethnomusicology.............................................................................................................13 2.2The Role of Music in constructing Identity.....................................................................16 2.3Music and Ethnic Identity in the Context of Cultural Diversity and Creolization..........20 3.Introducing Suriname.............................................................................................................23 4.Marrons..................................................................................................................................24 4.1Introducing Marrons .......................................................................................................24 -

How to Live an Eco-Friendly Lifestyle

How to Live an Eco-Friendly Lifestyle How to Live an Eco-Friendly Lifestyle by Wendy Wisner How to Live an Eco-Friendly Lifestyle How to Live an Eco-Friendly Lifestyle by Wendy Wisner It is increasingly clear that climate change is the defining issue of our time. Although scientists don’t agree on exactly how long it will take1, there is a consensus that the environment and possibly our very lives are in danger. Moreover, according to NASA2, there is a 95% probability that human activity is to blame for the rise in global temperature we’ve seen over the past few decades. Certainly changes need to be made on a societal level, but the onus is on every one of us to make conscious choices toward more eco-friendly lifestyles. It can feel overwhelming to consider what this might entail. Many of us feel stretched thin as it is — how can we possibly find the bandwidth to make substantial lifestyle changes? Plus, so many environmentally hazardous aspects of modern living feel out of our control. It’s not as though we can ditch our gas-guzzling cars on a whim, or stop purchasing any and all products made with non-sustainable materials. Change is hard, but you don’t have to do this all at once. Every effort you make toward a more eco-friendly lifestyle counts, and even a few small changes can really add up. It’s best to take a transformation like this gradually, which is why we’ve prepared a step-by-step guide.