Hindu Music in Bangkok: the Om Uma Devi Shiva Band

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

Case Study Vikas Marg, New Delhi Laxmi Nagar Chungi to Karkari Mor

Equitable Road Space : Case study Vikas Marg, New Delhi Laxmi Nagar Chungi to Karkari Mor PWD, Govt. of NCT of Delhi Methodology Adopted STAGE 1 : Understand Equitable Road Space and Design STAGE 2 : Study of different Guidelines. STAGE 3 : Identification of Case Study Location and Data Collection STAGE 4 : Data Analysis STAGE 5 : Design Considerations Need for Equitable Road Space Benefits of Equitable Design Increase in comfort of pedestrians Comfortable last mile connectivity from MRTS Stations – therefore increased ridership of Buses and Metro. Reduced dependency on the car, if shorter trips can be made comfortably by foot. Prioritization of public transport and non- motorized private modes in street design. Reduced car use leading to reduced congestion and pollution. More equity in the provision of comfortable public spaces and amenities to all sections Source: Street Design Guidelines © UTTIPEC, DDA 2009 of society. Guidelines of UTTIPEC for Equitable Road Space GOALS FOR “INTEGRATED” STREETS FOR DELHI: GOAL 1: • MOBILITY AND ACCCESSIBILITY – Maximum number of people should be able to move fast, safely and conveniently through the city. GOAL 2: • SAFETY AND COMFORT – Make streets safe clean and walkable, create climate sensitive design. GOAL 3: • ECOLOGY – Reduce impact on the natural environment; and Reduce pressure on built infrastructure. Mobility Goals: To ensure preferable public transport use: 1. To Retrofit Streets for equal or higher priority for Public Transit and Pedestrians. 2. Provide transit-oriented mixed land use patterns and redensify city within 10 minutes walk of MRTS stops. 3. Provide dedicated lanes for HOVs (high occupancy vehicles) and carpool during peak hours. Safety, Comfort Goals: 4. -

Ophthalmology

conferenceseries.com Announcement 3rd International Conference on Ophthalmology Theme: “Enhancing the Quality and Credibility of Ophthalmology” July 10-11, 2018 Bangkok Thailand Conference Secretariat One Commerce Center-1201, Orange St. #600 Wilmington, Zip 19899, Delaware, USA Tel: +1-888-843-8169, Fax: +1-650-618-1417 email: [email protected] [email protected] http://worldophthalmology.conferenceseries.com/ Invitation World Ophthalmology 2018 Dear Colleagues, Conference Series LLC is delighted to welcome you to Bangkok, Thailand for the prestigious 3rd International Conference on Ophthalmology. World Ophthalmology 2018 will focus on the theme “Enhancing the Quality and Credibility of Ophthalmology”. We are confident that you will enjoy the Scientific Program of this upcoming Conference. We look forward to see you at Bangkok, Thailand. With Regards, World Ophthalmology 2018 Operating Committee Conference Series Conferences Editorial Board Members of Supporting Journals: Richard B Rosen Chi-Chao Chan New York Medical College, USA National Institutes of Health, USA Stephen G Schwartz Kota V Ramana Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, USA The University of Texas Medical Raul Martin Branch, USA University of Valladolid, Spain Sudhakar Akul Yakkanti Sayon Roy Stanford Research Institute Boston University, USA International, USA Yoko Miura University of Luebeck, Germany World Ophthalmology 2018 Program Announcement Accommodation A large number of rooms have been reserved. Discounted room rates for World Ophthalmology 2018 participants are proposed. Only reservations made through the Conference will benefit these rates. The Congress Center can be easily reached by Public transportation. Exhibition and Sponsorship An Exhibition will be held concurrently with the Conference. The coffee break and lunch areas will be located adjacent to the booths. -

A Model for the Management of Cultural Tourism at Temples in Bangkok, Thailand

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 6, No. 2; 2014 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education A Model for the Management of Cultural Tourism at Temples in Bangkok, Thailand Phra Thanuthat Nasing1, Chamnan Rodhetbhai1 & Ying Keeratiburana1 1 The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand Correspondence: Phra Thanuthat Nasing, The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province 44150, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 20, 2014 Accepted: June 12, 2014 Online Published: June 26, 2014 doi:10.5539/ach.v6n2p242 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v6n2p242 Abstract This qualitative investigation aims to identify problems with cultural tourism in nine Thai temples and develop a model for improved tourism management. Data was collected by document research, observation, interview and focus group discussion. Results show that temples suffer from a lack of maintenance, poor service, inadequate tourist facilities, minimal community participation and inefficient public relations. A management model to combat these problems was designed by parties from each temple at a workshop. The model provides an eight-part strategy to increase the tourism potential of temples in Bangkok: temple site, safety, conveniences, attractions, services, public relations, cultural tourism and management. Keywords: management, cultural tourism, temples, Thailand, development 1. Introduction When Chao Phraya Chakri deposed King Taksin of the Thonburi Kingdom in 1982, he relocated the Siamese capital city to Bangkok and revived society under the name of his new Rattanakosin Kingdom (Prathepweti, 1995). Although royal monasteries had been commissioned much earlier in Thai history, there was a particular interest in their restoration during the reign of the Rattanakosin monarchs. -

Jagdish Prasad Sunil Kumar

+91-9811192425 Jagdish Prasad Sunil Kumar https://www.indiamart.com/jpskmusicalstore/ Founded in 1965, Jagdish Prasad Sunil Kumar is the foremost manufacturer, wholesaler and supplier of Tabla Musical Instruments, Naal Drums and Shruti Box. About Us Founded in 1965, Jagdish Prasad Sunil Kumar is the foremost manufacturer, wholesaler and supplier of Tabla Musical Instruments, Harmonium Musical Instrument, Dhol Musical Instrument, Dholak Musical Instrument, Swarmandal Musical Instruments, Santur Musical Instruments, Tanpura Musical Instruments, Khanjari Musical Instruments, Electronic Banjos, Pakhawaj Drums, Djembe Drums, Khol Drums, Naal Drums and Shruti Box. Our products are extremely well-liked owing to their top features and nominal prices. These products are made by professional’s team employing the advanced techniques and best quality material, which is bought from trustworthy sellers of market. Professionals manufacture these products as per universal industry parameters. Being a customer’s centric organization, professionals also make these products according our client’s requirements and necessities. Due to huge distribution network, fair business polices and quality-centric approach, we have gained trust of our patrons. Apart from, we work under the leadership of our mentor Ashish Verma. Under his supervision our firm has attained heights of success. We also provide many facilities to the patrons to put their demands forward and get them solve timely and as per their requirements. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/jpskmusicalstore/profile.html -

Infrastructure

INFRASTRUCTURE Bangkok has been undergoing rapid urbanization and industrialization since 1960. The increasing population is due in part to the development of infrastructure, such as road networks, real estate developments, land value, and a growing economy that resulted in expansion into the surrounding areas and the migration of people to the city from all parts of the country. 7>ÌiÀÊ ÃÕ«ÌÊÊ >}Ê>`Ê6VÌÞÊÀi> Õ°° Discovering the City the Discovering City the Discovering xxÈ°Ó Èää x£È°Ó xän°£ {nÈ°Î {n°È {ÇÈ°Ç {ää Óää ££°Ç È°{ n°£ ä ÓääÓ ÓääÎ Óää{ , - / *1 Ê7/ ,Ê-1**9Ê Ê"/ ,- 1- --]Ê-// Ê / ,*,- ]Ê"6¿/Ê 9Ê Ê 1-/, Source: Metropolitan Waterworks Authority /Ì>Ê7>ÌiÀÊ*À`ÕVÌÊÉÊ Water Management ->iÃÊÊ >}Ê>`Ê6VÌÞÊÀi> At present, the Metropolitan Waterworks To develop an effl uent treatment system, To build walls to prevent and solve Authority (MWA) provides the public and establish a “Flood Control Center” fl ood problems caused by seasonal, water supply in the BMA, Nonthaburi with 55 network stations, using low-cost northern and marine overfl ows in the and Samut Prakarn provinces at an treatment techniques and building Bangkok area. Ê Õ°° average of 4.15 million cubic meters additional water treatment systems, while Ó]äää per day, over a 1,486.5 sq. km area. restoring the beauty and cleanliness To develop an information technology £]xÎn°Î £]xää £]xäx £]x£È°£ of canals and rivers. system to support drainage systems £]{n£°Ç £]{În°x £]äÇÈ The BMA continuously monitors the throughout Bangkok. £]äää È°{ £]ä£Î° Ó°x nnä°Î quality of the water supply and canals. -

NDMC Ward No. 001 S

NDMC Ward No. 001 S. No. Ward Name of Name of Name of Enumeratio Extent of the Population Enumeration Total SC % of SC Name & town/Census District & Tahsil & n Block No. Block Population Population Population Code Town/ Village Code Code 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0021(1) Devi Prasad Sadan 1-64, NDMC Flats 4 Place 001 Type-6, Asha Deep Apartment 9 Hailey 1 Road 44 Flats 656 487 74.24 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0029 Sangli Mess Cluster (Slum) 2 Place 001 351 174 49.57 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0031(2) Feroz Shah Road, Canning Lane Kerala 3 Place 001 School 593 212 35.75 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0032(1) Princess Park Residential Area Copper 4 Place 001 Nicus Marg to Tilak Marg, 100 Houses 276 154 55.8 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0032(2) Princess Park Residential Area Copper 5 Place 001 Nicus Marg to Tilak Marg, 105 Houses 312 142 45.51 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0036(1) NSCI Club Cluster-171 Houses 6 Place 001 521 226 43.38 NDMC Ward No. 002 Ward Name of Name of Name of Enumeratio Extent of the Population Enumeration Total SC % of SC Name & town/Census District & Tahsil & n Block No. Block Population Population Population S. No. Code Town/ Village Code Code Parliament A1 to H18 CN 1 to 10 Palika Dham Bhai Vir 0002 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 0005-1 933 826 88.53 1 Street 003 Singh Marg Block 5 Jain Mandir Marg ,Vidhya Bhawan Parliament 0002 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 0009 ,Union Acadmy Colony 70 A -81 H Arya 585 208 35.56 Street 003 2 School Lane Parliament 1-126 Mandir Marg R.K. -

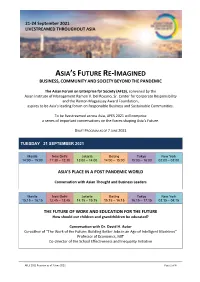

AFES 2021 Program As of 7 June 2021 Page 1 of 4

21-24 September 2021 LIVESTREAMED THROUGHOUT ASIA ASIA’S FUTURE RE-IMAGINED BUSINESS, COMMUNITY AND SOCIETY BEYOND THE PANDEMIC The Asian Forum on Enterprise for Society (AFES), convened by the Asian Institute of Management Ramon V. Del Rosario, Sr. Center for Corporate Responsibility and the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation, aspires to be Asia’s leading forum on Responsible Business and Sustainable Communities. To be livestreamed across Asia, AFES 2021 will comprise a series of important conversations on the forces shaping Asia’s Future. DRAFT PROGRAM AS OF 7 JUNE 2021 TUESDAY 21 SEPTEMBER 2021 Manila New Delhi Jakarta Beijing Tokyo New York 14:00 – 15:00 11:30 – 12:30 13:00 – 14:00 14:00 – 15:00 15:00 – 16:00 02:00 – 03:00 ASIA’S PLACE IN A POST PANDEMIC WORLD Conversation with Asian Thought and Business Leaders Manila New Delhi Jakarta Beijing Tokyo New York 15:15 – 16:15 12:45 – 13:45 14:15 – 15:15 15:15 – 16:15 16:15 – 17:15 03:15 – 04:15 THE FUTURE OF WORK AND EDUCATION FOR THE FUTURE How should our children and grandchildren be educated? Conversation with Dr. David H. Autor Co-author of “The Work of the Future: Building Better Jobs in an Age of Intelligent Machines” Professor of Economics, MIT Co-director of the School Effectiveness and Inequality Initiative AFES 2021 Program as of 7 June 2021 Page 1 of 4 21-24 September 2021 LIVESTREAMED THROUGHOUT ASIA TUESDAY 21 SEPTEMBER 2021 Manila New Delhi Jakarta Beijing Tokyo New York 16:30 – 17:45 14:00 – 15:15 15:30 – 16:45 16:30 – 17:45 17:30 – 18:45 04:30 – 05:45 TECHNOLOGY, INNOVATION AND COMMUNITY The Acceleration of Digitalization and AI will bring extraordinary efficiency gains but also much greater inequality. -

25 Handbook of Bibliography on Diaspora and Transnationalism.Pdf

BIBLIOGRAPH Y A Hand-book on Diaspora and Transnationalism FIRST EDITION April 2013 Compiled By Monika Bisht Rakesh Ranjan Sadananda Sahoo Draft Copy for Reader’s Comments Global Research Forum on Diaspora and Transnationalism www.grfdt.org Bibleography Preface Large scale international mobility of the people since colonial times has been one of the most important historical phenomenon in the human history. This has impacted upon the social, cultural, political and economic landscape of the entire globe. Though academic interest goes back little early, the phenomenon got the world wide attention as late as 1990s. We have witnessed more proactive engagement of various organizations at national and international level such as UN bodies. There was also growing research interest in the areas. Large number of institutions got engaged in research on diaspora-international migration-refugee-transnationalism. Wide range of research and publications in these areas gave a new thrust to the entire issue and hence advancing further research. The recent emphasis on diaspora’s development role further accentuated the attention of policy makers towards diaspora. The most underemphasized perhaps, the role of diaspora and transnational actors in the overall development process through capacity building, resource mobilization, knowledge sharing etc. are growing areas of development debate in national as well as international forums. There have been policy initiatives at both national and international level to engage diaspora more meaningfully since last one decade. There is a need for more wholistic understanding of the enrite phenomena to facilitate researchers and stakeholders engaged in the various issues related to diaspora and transnationalism. Similarly, we find the areas such as social, political and cultural vis a vis diaspora also attracting more interest in recent times as forces of globalization intensified in multi direction. -

TOT for Urban Climate Change Adaptation in Southeast Asia

Building Capacity for Urban Climate Change Adaptation in Southeast Asia Project Reference: CBA2016-01CMY-Boonjawat Project Leader Dr. Jariya Boonjawat Southeast Asia START Regional Center, Chulalongkorn University Bangkok, Thailand [email protected] Project Collaborators: Cambodia: Prof. Dr. Veasna Kum, Pannasastra University of Cambodia [email protected] Indonesia: Dr. Erna Sri Adiningsih, Remote Sensing Application Center, Indonesian National Institute of Aeronautics and Space (LAPAN), Indonesia [email protected]; [email protected] Lao PDR: Dr. Virasack Chundara, Natural Resources and Environment Institute, Ministry of Naturel Resource and Environment, Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR [email protected] Malaysia: Prof. Dr. Er Ah Choy, University of Kebangsaan, Malaysia [email protected] Philippines: Prof. Dr. Mario Delos Reyes , University of the Philippines [email protected] Thailand: Dr. Penjai Sompongchaikul, Director SEA START RC, Chulalongkorn University [email protected] USA: Dr. Robert John Dobias, USAID-ADAPT Asia and Advisor, NRCT [email protected] Vietnam: Dr. Ngo Kim Chi, INPE, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Hanoi, Vietnam [email protected]; [email protected] Countries involved: Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, USA, Vietnam Project Duration: 2 yrs (CBA2015-03NMY-Adiningsih; CBA2016-01CMY-Boonjawat) APN Fund USD: 40,000 (Year 2) Year of Completion: 2018 Project Output: Participants Guide Book for the 2nd Training of Trainers (TOT2) for Urban Climate Change Adaptation -

A Critical Analysis of Narrative Art on Baranagar Temple Facades

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Special Conference Issue (Vol. 12, No. 5, 2020. 1-18) from 1st Rupkatha International Open Conference on Recent Advances in Interdisciplinary Humanities (rioc.rupkatha.com) Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V12/n5/rioc1s16n2.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n5.rioc1s16n2 Unraveling the Social Position of Women in Late-Medieval Bengal: A Critical Analysis of Narrative Art on Baranagar Temple Facades Bikas Karmakar1 & Ila Gupta2 1Assistant Professor, Government College of Art & Craft Calcutta [email protected] 2Former Professor, Department of Architecture & Planning, IIT Roorkee [email protected] Abstract The genesis of the present study can be traced to an aspiration to work on the narratives of religious architecture. The Terracotta Temples of Baranagar in Murshidabad, West Bengal offer a very insightful vantage point in this regard. The elaborate works of terracotta on the facades of these temples patronized by Rani Bhabani during the mid-eighteenth century possess immense narrative potential to reconstruct the history of the area in the given time period. The portrayals on various facets of society, environment, culture, religion, mythology, and space and communication systems make these temples exemplary representatives for studying narrative art. While a significant portion of the temple facades depicts gods, goddesses, and mythological stories, the on-spot study also found a substantial number of plaques observed mainly on the base friezes representing the engagement of women in various mundane activities. This study explores the narrative intentions of such portrayals. The depictions incorporated are validated with various types of archival evidence facilitating cross-corroboration of the sources. -

Hindu Music from Various Authors, Pom.Pil.Ed and J^Ublished

' ' : '.."-","' i / i : .: \ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY MUSIC e VerSl,y Ubrary ML 338.fl2 i882 3 1924 022 411 650 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 92402241 1 650 " HINDU MUSIC FROM VARIOUS AUTHORS, POM.PIL.ED AND J^UBLISHED RAJAH COMM. SOURINDRO MOHUN TAGORE, MUS. DOC.J F.R.S.L., M.U.A.S., Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire ; KNIGHT COMMANDER OF THE FIRST CLASS OF THE ORDER OF ALBERT, SAXONY ; OF THE ORDER OF LEOPOLD, BELGIUM ; FRANCIS OF THE MOST EXALTED ORDEE OF JOSEPH, AUSTRIA ; OF THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE CROWN OF ITALY ; OF THE MOST DISTINGUISHED ORDER OF DANNEBROG, DENMARK ; AND OF THE ROYAL ORDER OF MELTJSINE OF PRINCESS MARY OF LUSIGNAN ; FRANC CHEVALIER OF THE ORDER OF THE KNIGHTS OF THE MONT-REAL, JERUSALEM, RHODES HOLY SAVIOUR OF AND MALTA ; COMMANDEUR DE ORDRE RELIGIEOX ET MILITAIRE DE SAINT-SAUVEUR DE MONT-REAL, DE SAINT-JEAN DE JERUSALEM, TEMPLE, SAINT SEPULCRE, DE RHODES ET MALTE DU DU REFORME ; KNIGHT OF THE FIRST CLASS OF THE IMPERIAL ORDER OF THE " PAOU SING," OR PRECIOUS STAR, CHINA ; OF THE SECOND CLASS OF THE HIGH IMPERIAL ORDER OF THE LION AND SUN, PERSIA; OF THE SECOND CLASS OF THE IMPERIAL ORDER OF MEDJIDIE, TURKEY ; OF THE ROYAL MILITARY ORDER OF CHRIST, AND PORTUGAL ; KNIGHT THE OF BASABAMALA, OF ORDER SIAM ; AND OF THE GURKHA STAR, NEPAL ; " NAWAB SHAHZADA FROM THE SHAH OF PERSIA, &C, &C, &C.