SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Circumambulation in Indian Pilgrimage: Meaning And

232 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & ENGINEERING RESEARCH, VOLUME 12, ISSUE 1, JANUARY-2021 ISSN 2229-5518 Circumambulation in Indian pilgrimage: Meaning and manifestation Santosh Kumar Abstract— Our ancient literature is full of examples where pilgrimage became an immensely popular way of achieving spiritual aims while walking. In India, many communities have attached spiritual importance to particular places or to the place where people feel a spiritual awakening. Circumambulation (pradakshina) around that sacred place becomes the key point of prayer and offering. All these circumambulation spaces are associated with the shrines or sacred places referring to auspicious symbolism. In Indian tradition, circumambulation has been practice in multiple scales ranging from a deity or tree to sacred hill, river, and city. The spatial character of the path, route, and street, shift from an inside dwelling to outside in nature or city, depending upon the central symbolism. The experience of the space while walking through sacred space remodel people's mental and physical character. As a result, not only the sacred space but their design and physical characteristics can be both meaningful and valuable to the public. This research has been done by exploring in two stage to finalize the conclusion, In which First stage will involve a literature exploration of Hindu and Buddhist scripture to understand the meaning and significance of circumambulation and in second, will investigate the architectural manifestation of various element in circumambulatory which help to attain its meaning and true purpose. Index Terms— Pilgrimage, Circumambulation, Spatial, Sacred, Path, Hinduism, Temple architecture —————————— —————————— 1 Introduction Circumambulation ‘Pradakshinā’, According to Rig Vedic single light source falling upon central symbolism plays a verses1, 'Pra’ used as a prefix to the verb and takes on the vital role. -

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

In the Hindu Temples of Kerala Gilles Tarabout

Spots of Wilderness. ’Nature’ in the Hindu Temples of Kerala Gilles Tarabout To cite this version: Gilles Tarabout. Spots of Wilderness. ’Nature’ in the Hindu Temples of Kerala. Rivista degli Studi Orientali, Fabrizio Serra editore, 2015, The Human Person and Nature in Classical and Modern India, eds. R. Torella & G. Milanetti, Supplemento n°2 alla Rivista Degli Studi Orientali, n.s., vol. LXXXVIII, pp.23-43. hal-01306640 HAL Id: hal-01306640 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01306640 Submitted on 25 Apr 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Published in Supplemento n°2 alla Rivista Degli Studi Orientali, n.s., vol. LXXXVIII, 2015 (‘The Human Person and Nature in Classical and Modern India’, R. Torella & G. Milanetti, eds.), pp.23-43; in the publication the photos are in B & W. /p. 23/ Spots of Wilderness. ‘Nature’ in the Hindu Temples of Kerala Gilles Tarabout CNRS, Laboratoire d’Ethnologie et de Sociologie Comparative Many Hindu temples in Kerala are called ‘groves’ (kāvu), and encapsulate an effective grove – a small spot where shrubs and trees are said to grow ‘wildly’. There live numerous divine entities, serpent gods and other ambivalent deities or ghosts, subordinated to the presiding god/goddess of the temple installed in the main shrine. -

The Science Behind Sandhya Vandanam

|| 1 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 Sri Vaidya Veeraraghavan – Nacchiyar Thirukkolam - Thiruevvul 2 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 �ी:|| ||�ीमते ल�मीनृिस륍हपर��णे नमः || Sri Nrisimha Priya ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ AN AU T H O R I S E D PU B L I C A T I O N OF SR I AH O B I L A M A T H A M H. H. 45th Jiyar of Sri Ahobila Matham H.H. 46th Jiyar of Sri Ahobila Matham Founder Sri Nrisimhapriya (E) H.H. Sri Lakshminrisimha H.H. Srivan Sathakopa Divya Paduka Sevaka Srivan Sathakopa Sri Ranganatha Yatindra Mahadesikan Sri Narayana Yatindra Mahadesikan Ahobile Garudasaila madhye The English edition of Sri Nrisimhapriya not only krpavasat kalpita sannidhanam / brings to its readers the wisdom of Vaishnavite Lakshmya samalingita vama bhagam tenets every month, but also serves as a link LakshmiNrsimham Saranam prapadye // between Sri Matham and its disciples. We confer Narayana yatindrasya krpaya'ngilaraginam / our benediction upon Sri Nrisimhapriya (English) Sukhabodhaya tattvanam patrikeyam prakasyate // for achieving a spectacular increase in readership SriNrsimhapriya hyesha pratigeham sada vaset / and for its readers to acquire spiritual wisdom Pathithranam ca lokanam karotu Nrharirhitam // and enlightenment. It would give us pleasure to see all devotees patronize this spiritual journal by The English Monthly Edition of Sri Nrisimhapriya is becoming subscribers. being published for the benefit of those who are better placed to understand the Vedantic truths through the medium of English. May this magazine have a glorious growth and shine in the homes of the countless devotees of Lord Sri Lakshmi Nrisimha! May the Lord shower His benign blessings on all those who read it! 3 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 4 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 ी:|| ||�ीमते ल�मीनृिस륍हपर��णे नमः || CONTENTS Sri Nrisimha Priya Owner: Panchanga Sangraham 6 H.H. -

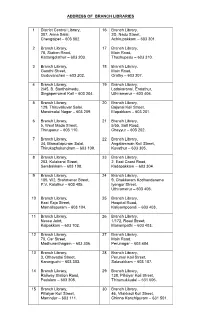

Branch Libraries List

ADDRESS OF BRANCH LIBRARIES 1 District Central Library, 16 Branch Library, 307, Anna Salai, 2D, Nadu Street, Chengalpet – 603 002. Achirupakkam – 603 301. 2 Branch Library, 17 Branch Library, 78, Station Road, Main Road, Kattangolathur – 603 203. Thozhupedu – 603 310. 3 Branch Library, 18 Branch Library, Gandhi Street, Main Road, Guduvancheri – 603 202. Orathy – 603 307. 4 Branch Library, 19 Branch Library, 2/45, B. Santhaimedu, Ladakaranai, Endathur, Singaperrumal Koil – 603 204. Uthiramerur – 603 406. 5 Branch Library, 20 Branch Library, 129, Thiruvalluvar Salai, Bajanai Koil Street, Maraimalai Nagar – 603 209. Elapakkam – 603 201. 6 Branch Library, 21 Branch Library, 5, West Mada Street, 5/55, Salt Road, Thiruporur – 603 110. Cheyyur – 603 202. 7 Branch Library, 22 Branch Library, 34, Mamallapuram Salai, Angalamman Koil Street, Thirukazhukundram – 603 109. Kuvathur – 603 305. 8 Branch Library, 23 Branch Library, 203, Kulakarai Street, 2, East Coast Road, Sembakkam – 603 108. Kadapakkam – 603 304. 9 Branch Library, 24 Branch Library, 105, W2, Brahmanar Street, 9, Chakkaram Kodhandarama P.V. Kalathur – 603 405. Iyengar Street, Uthiramerur – 603 406. 10 Branch Library, 25 Branch Library, East Raja Street, Hospital Road, Mamallapuram – 603 104. Kaliyampoondi – 603 403. 11 Branch Library, 26 Branch Library, Nesco Joint, 1/172, Road Street, Kalpakkam – 603 102. Manampathi – 603 403. 12 Branch Library, 27 Branch Library, 70, Car Street, Main Road, Madhuranthagam – 603 306. Perunagar – 603 404. 13 Branch Library, 28 Branch Library, 3, Othavadai Street, Perumal Koil Street, Karunguzhi – 603 303. Salavakkam – 603 107. 14 Branch Library, 29 Branch Library, Railway Station Road, 138, Pillaiyar Koil Street, Padalam – 603 308. -

In the Kingdom of Nataraja, a Guide to the Temples, Beliefs and People of Tamil Nadu

* In the Kingdom of Nataraja, a guide to the temples, beliefs and people of Tamil Nadu The South India Saiva Siddhantha Works Publishing Society, Tinnevelly, Ltd, Madras, 1993. I.S.B.N.: 0-9661496-2-9 Copyright © 1993 Chantal Boulanger. All rights reserved. This book is in shareware. You may read it or print it for your personal use if you pay the contribution. This document may not be included in any for-profit compilation or bundled with any other for-profit package, except with prior written consent from the author, Chantal Boulanger. This document may be distributed freely on on-line services and by users groups, except where noted above, provided it is distributed unmodified. Except for what is specified above, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system - except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper - without permission in writing from the author. It may not be sold for profit or included with other software, products, publications, or services which are sold for profit without the permission of the author. You expressly acknowledge and agree that use of this document is at your exclusive risk. It is provided “AS IS” and without any warranty of any kind, expressed or implied, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. If you wish to include this book on a CD-ROM as part of a freeware/shareware collection, Web browser or book, I ask that you send me a complimentary copy of the product to my address. -

Ficus Religiosa: a Wholesome Medicinal Tree

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2018; 7(4): 32-37 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 JPP 2018; 7(4): 32-37 Ficus religiosa: A wholesome medicinal tree Received: 21-05-2018 Accepted: 25-06-2018 Sandeep, Ashwani Kumar, Dimple, Vidisha Tomer, Yogesh Gat and Sandeep Vikas Kumar Dept. of Food Science and Nutrition, School of Agriculture, Lovely Professional University, Abstract Phagwara, Punjab, India Medicinal plants play a vital role in improving health of people. Hundreds of medicinal plants have been used to cure various diseases since ancient times. Ficus religiosa (Peepal) has an important place among Ashwani Kumar herbal plants. Almost every part of this tree i.e. leaves, bark, seeds and fruits are used in the preparation Dept. of Food Science and of herbal medicines. Therapeutic properties of this tree in curing a wide range of diseases can be Nutrition, School of Agriculture, attributed to its richness in bioactive compounds namely flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, saponins, phenols Lovely Professional University, etc. Its antimicrobial, anti-diabetic, anticonvulsant, wound healing, anti-inflammatory and analgesic Phagwara, Punjab, India properties have made it a popular herbal tree and its parts are placed as important ingredient in modern pharmacological industry. The documentation of traditional and modern usage of F. religiosa under one Dimple Dept. of Food Science and heading can help researchers to design and develop new functional foods from F. religiosa. Nutrition, School of Agriculture, Lovely Professional University, Keywords: Ficus religiosa, bioactive compounds, nutritional composition, medicinal properties Phagwara, Punjab, India Introduction Vidisha Tomer Genus Ficus has 750 species of woody plants, from which Ficus religiosa is one of the Dept. -

Scientific Insights in the Preparation and Characterisation of a Lead-Based Naga Bhasma

Research Paper Scientific Insights in the Preparation and Characterisation of a Lead-based Naga Bhasma S. NAGARAJAN1,2, S. KRISHNASWAMY2, BRINDHA PEMIAH2,3, K. S. RAJAN1,2, UMAMAHESWARI KRISHNAN1,2, AND S. SETHURAMAN1,2* 1Centre for Nanotechnology and Advanced Biomaterials, 2School of Chemical and Biotechnology, 3Centre for Advanced Research in Indian System of Medicine, Sastra University, Thanjavur‑613 401, India Nagarajan, et al.: Science of Preparation of Naga Bhasma Naga bhasma is one of the herbo-metallic preparations used in Ayurveda, a traditional Indian System of Medicine. The preparation of Naga bhasma involves thermal treatment of ‘Naga’ (metallic lead) in a series of quenching liquids, followed by reaction with realgar and herbal constituents, before calcination to prepare a fine product. We have analysed the intermediates obtained during different stages of preparation to understand the relevance and importance of different steps involved in the preparation. Our results show that ‘Sodhana’ (purification process) removes heavy metals other than lead, apart from making it soft and amenable for trituration. The use of powders of tamarind bark and peepal bark maintains the oxidation state of lead in Jarita Naga (lead oxide) as Pb2+. The repeated calcination steps result in the formation of nano-crystalline lead sulphide, the main chemical species present in Naga bhasma. Key words: Sodhana (purification),naga bhasma, lead, lead oxide, lead sulphide, calcination Ayurveda, an ancient system of medicine, has been at 6 mg/kg body weight was found to be nontoxic practiced in India since time immemorial. Plants, in animal model[7]. Naga bhasma has specific minerals, molecules from animal sources are used regenerative potential on germinal epithelium of [8] for the preparation of Ayurvedic drugs. -

Architecture of Light of the Orthodox Temple

DOI: 10.4467/25438700ŚM.17.058.7679 MYROSLAV YATSIV* Architecture of Light of the Orthodox Temple Abstract Main tendencies, appropriateness and features of the embodiment of the architectural and theological essence of the light are defined in architecturally spatial organization of the Orthodox Church; the value of the natural and artificial light is set in forming of symbolic structure of sacral space and architectonics of the church building. Keywords: the Orthodox Church, sacral space, the light, architectonics, functions of the light, a system of illumination, principles of illumination 1. Introduction. The problem raising in such aspect it’s necessary to examine es- As the experience of new-built churches testifies, a process sence and value of the light in space of the of re-conceiving of national traditions and searches of com- Orthodox Church. bination of modern constructions and building technologies In religion and spiritual life of believing peo- last with the traditional architectonic forms of the church bu- ple the light is an important and meaningful ilding in modern church architecture of Ukraine. Some archi- symbol of combination in their imagination tects go by borrowing forms of the Old Russian church archi- of the celestial and earthly worlds. Through tecture, other consider it’s better to inherit the best traditions this it occupies a central place among reli- of wooden and stone churches of the Ukrainian baroque or gious characters which are used in the Saint- realize the ideas of church architecture of the beginning of ed Letter. From the first book of Old Testa- XX. In the east areas the volume-spatial composition of the ment, where the fact of creation of the light Russian “synod-empire” of the church style is renovated as by God is specified: “And God said: “Let it be the “national sign of church architecture” and interpreted as light!”(Genesis 1.3-4), to the last New Testa- the new “Ukrainian Renaissance” [1]. -

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020 (3 credits; MW 10:05-11:25; Oegema; Zoom & Recorded) Instructor: Prof. Dr. Gerbern S. Oegema Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University 3520 University Street Office hours: by appointment Tel. 398-4126 Fax 398-6665 Email: [email protected] Prerequisite: This course presupposes some basic knowledge typically but not exclusively acquired in any of the introductory courses in Hebrew Bible (The Religion of Ancient Israel; Literature of Ancient Israel 1 or 2; The Bible and Western Culture), New Testament (Jesus of Nazareth, New Testament Studies 1 or 2) or Rabbinic Judaism. Contents: The course is meant for undergraduates, who want to learn more about the history of Ancient Judaism, which roughly dates from 300 BCE to 200 CE. In this period, which is characterized by a growing Greek and Roman influence on the Jewish culture in Palestine and in the Diaspora, the canon of the Hebrew Bible came to a close, the Biblical books were translated into Greek, the Jewish people lost their national independence, and, most important, two new religions came into being: Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism. In the course, which is divided into three modules of each four weeks, we will learn more about the main historical events and the political parties (Hasmonaeans, Sadducees, Pharisees, Essenes, etc.), the religious and philosophical concepts of the period (Torah, Ethics, Freedom, Political Ideals, Messianic Kingdom, Afterlife, etc.), and the various Torah interpretations of the time. A basic knowledge of this period is therefore essential for a deeper understanding of the formation of the two new religions, Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism, and for a better understanding of the growing importance, history and Biblical interpretation have had for Ancient Judaism. -

SAJB-16290-296.Pdf

Scholars Academic Journal of Biosciences (SAJB) ISSN 2321-6883 Sch. Acad. J. Biosci., 2013; 1(6):290-296 ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publisher (An International Publisher for Academic and Scientific Resources) www.saspublisher.com Research Article A study on two important environmental services of urban trees to disseminate the economic importance of trees to student community P. Pachaiyappan, D. Ushalaya Raj Institute of Advanced Study in Education, Saidapet, Chennai – 600 015, Tamil Nadu, India *Corresponding author P. Pachaiyappan Email: Abstract: Trees provide innumerable ecosystem services in human-dominated urban environment. Forest disturbances as well as biomass enrichments are tightly linked with atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration. All trees ≥5 cm diameter at breast height (dbh) were inventoried from a one hectare area of the Cooum river bank (CRB), Chennai Metropolitan city (CMC), India. Both above and below ground biomass were estimated by widely accepted regression equations with DBH and wood density as inputs. A total of 710 trees belonged to 22 families, 41 genera and 47 species were recorded. Trees accumulated 86.02 Mg dry biomass and 43.01 Mg C in a hectare. Members of Mimosaceae dominated the CRB with 231 individuals. Tamarindus indica contributed more (11.744 Mg; 13.7%) to biomass. As to the families Ceasalpiniaceae, Mimosaceae and Papilionaceae altogether contributed 55.61 Mg (64.64%) to total biomass. Tree diameter class 31-45 cm contributed more (35.15 Mg; 40.86%) to total biomass. On average each tree achieved 0.47 ± 0.1 cm dbh growth yr-1. In a year one hectare urban forest sequestered 3999.91 kg biomass and 1999.95 kg C.