In the Kingdom of Nataraja, a Guide to the Temples, Beliefs and People of Tamil Nadu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guru: by Various Authors

Divya Darshan Contributors; Publisher Pt Narayan Bhatt Guru Purnima: Hindu Heritage Society ABN 60486249887 Smt Lalita Singh Sanskriti Divas Medley Avenue Liverpool NSW 2170 Issue Pt Jagdish Maharaj Na tu mam shakyase drashtumanenaiv svachakshusha I Divyam dadami te chakshu pashay me yogameshwaram Your external eyes will not be able to comprehend my Divine form. I grant you the Divine Eye to enable you to This issue includes; behold Me in my Divine Yoga. Gita Chapter 11. Guru Mahima Guru Purnima or Sanskriti Diwas Krishnam Vande Jagad Gurum The Guru: by various Authors Message of the Guru Teaching of Raman Maharshi Guru and Disciple Hindu Sects Non Hindu Sects The Greatness of the Guru Prayer of Guru Next Issue Sri Krishna – The Guru of All Gurus VASUDEV SUTAM DEVAM KANSA CHANUR MARDAMAN DEVKI PARAMAANANDAM KRISHANAM VANDE JAGADGURUM I do vandana (glorification) of Lord Krishna, the resplendent son of Vasudev, who killed the great tormentors like Kamsa and Chanoora, who is a source of greatest joy to Devaki, and who is indeed a Jagad Guru (world teacher). 1 | P a g e Guru Mahima Sab Dharti Kagaz Karu, Lekhan Ban Raye Sath Samundra Ki Mas Karu Guru Gun Likha Na Jaye ~ Kabir This beautiful doha (couplet) is by the great saint Kabir. The meaning of this doha is “Even if the whole earth is transformed into paper with all the big trees made into pens and if the entire water in the seven oceans are transformed into writing ink, even then the glories of the Guru cannot be written. So much is the greatness of the Guru.” Guru means a teacher, master, mentor etc. -

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

Circumambulation in Indian Pilgrimage: Meaning And

232 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & ENGINEERING RESEARCH, VOLUME 12, ISSUE 1, JANUARY-2021 ISSN 2229-5518 Circumambulation in Indian pilgrimage: Meaning and manifestation Santosh Kumar Abstract— Our ancient literature is full of examples where pilgrimage became an immensely popular way of achieving spiritual aims while walking. In India, many communities have attached spiritual importance to particular places or to the place where people feel a spiritual awakening. Circumambulation (pradakshina) around that sacred place becomes the key point of prayer and offering. All these circumambulation spaces are associated with the shrines or sacred places referring to auspicious symbolism. In Indian tradition, circumambulation has been practice in multiple scales ranging from a deity or tree to sacred hill, river, and city. The spatial character of the path, route, and street, shift from an inside dwelling to outside in nature or city, depending upon the central symbolism. The experience of the space while walking through sacred space remodel people's mental and physical character. As a result, not only the sacred space but their design and physical characteristics can be both meaningful and valuable to the public. This research has been done by exploring in two stage to finalize the conclusion, In which First stage will involve a literature exploration of Hindu and Buddhist scripture to understand the meaning and significance of circumambulation and in second, will investigate the architectural manifestation of various element in circumambulatory which help to attain its meaning and true purpose. Index Terms— Pilgrimage, Circumambulation, Spatial, Sacred, Path, Hinduism, Temple architecture —————————— —————————— 1 Introduction Circumambulation ‘Pradakshinā’, According to Rig Vedic single light source falling upon central symbolism plays a verses1, 'Pra’ used as a prefix to the verb and takes on the vital role. -

Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R

THE PALGRAVE MACMILLAN ANIMAL ETHICS SERIES Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series Series Editors Andrew Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK Priscilla N. Cohn Pennsylvania State University Villanova, PA, USA Associate Editor Clair Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the ethics of our treatment of animals. Philosophers have led the way, and now a range of other scholars have followed from historians to social scientists. From being a marginal issue, animals have become an emerging issue in ethics and in multidisciplinary inquiry. Tis series will explore the challenges that Animal Ethics poses, both conceptually and practically, to traditional understandings of human-animal relations. Specifcally, the Series will: • provide a range of key introductory and advanced texts that map out ethical positions on animals • publish pioneering work written by new, as well as accomplished, scholars; • produce texts from a variety of disciplines that are multidisciplinary in character or have multidisciplinary relevance. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14421 Kenneth R. Valpey Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies Oxford, UK Te Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series ISBN 978-3-030-28407-7 ISBN 978-3-030-28408-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28408-4 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2020. Tis book is an open access publication. Open Access Tis book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

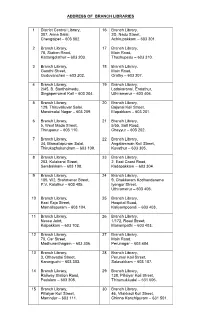

Branch Libraries List

ADDRESS OF BRANCH LIBRARIES 1 District Central Library, 16 Branch Library, 307, Anna Salai, 2D, Nadu Street, Chengalpet – 603 002. Achirupakkam – 603 301. 2 Branch Library, 17 Branch Library, 78, Station Road, Main Road, Kattangolathur – 603 203. Thozhupedu – 603 310. 3 Branch Library, 18 Branch Library, Gandhi Street, Main Road, Guduvancheri – 603 202. Orathy – 603 307. 4 Branch Library, 19 Branch Library, 2/45, B. Santhaimedu, Ladakaranai, Endathur, Singaperrumal Koil – 603 204. Uthiramerur – 603 406. 5 Branch Library, 20 Branch Library, 129, Thiruvalluvar Salai, Bajanai Koil Street, Maraimalai Nagar – 603 209. Elapakkam – 603 201. 6 Branch Library, 21 Branch Library, 5, West Mada Street, 5/55, Salt Road, Thiruporur – 603 110. Cheyyur – 603 202. 7 Branch Library, 22 Branch Library, 34, Mamallapuram Salai, Angalamman Koil Street, Thirukazhukundram – 603 109. Kuvathur – 603 305. 8 Branch Library, 23 Branch Library, 203, Kulakarai Street, 2, East Coast Road, Sembakkam – 603 108. Kadapakkam – 603 304. 9 Branch Library, 24 Branch Library, 105, W2, Brahmanar Street, 9, Chakkaram Kodhandarama P.V. Kalathur – 603 405. Iyengar Street, Uthiramerur – 603 406. 10 Branch Library, 25 Branch Library, East Raja Street, Hospital Road, Mamallapuram – 603 104. Kaliyampoondi – 603 403. 11 Branch Library, 26 Branch Library, Nesco Joint, 1/172, Road Street, Kalpakkam – 603 102. Manampathi – 603 403. 12 Branch Library, 27 Branch Library, 70, Car Street, Main Road, Madhuranthagam – 603 306. Perunagar – 603 404. 13 Branch Library, 28 Branch Library, 3, Othavadai Street, Perumal Koil Street, Karunguzhi – 603 303. Salavakkam – 603 107. 14 Branch Library, 29 Branch Library, Railway Station Road, 138, Pillaiyar Koil Street, Padalam – 603 308. -

Ficus Religiosa: a Wholesome Medicinal Tree

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2018; 7(4): 32-37 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 JPP 2018; 7(4): 32-37 Ficus religiosa: A wholesome medicinal tree Received: 21-05-2018 Accepted: 25-06-2018 Sandeep, Ashwani Kumar, Dimple, Vidisha Tomer, Yogesh Gat and Sandeep Vikas Kumar Dept. of Food Science and Nutrition, School of Agriculture, Lovely Professional University, Abstract Phagwara, Punjab, India Medicinal plants play a vital role in improving health of people. Hundreds of medicinal plants have been used to cure various diseases since ancient times. Ficus religiosa (Peepal) has an important place among Ashwani Kumar herbal plants. Almost every part of this tree i.e. leaves, bark, seeds and fruits are used in the preparation Dept. of Food Science and of herbal medicines. Therapeutic properties of this tree in curing a wide range of diseases can be Nutrition, School of Agriculture, attributed to its richness in bioactive compounds namely flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, saponins, phenols Lovely Professional University, etc. Its antimicrobial, anti-diabetic, anticonvulsant, wound healing, anti-inflammatory and analgesic Phagwara, Punjab, India properties have made it a popular herbal tree and its parts are placed as important ingredient in modern pharmacological industry. The documentation of traditional and modern usage of F. religiosa under one Dimple Dept. of Food Science and heading can help researchers to design and develop new functional foods from F. religiosa. Nutrition, School of Agriculture, Lovely Professional University, Keywords: Ficus religiosa, bioactive compounds, nutritional composition, medicinal properties Phagwara, Punjab, India Introduction Vidisha Tomer Genus Ficus has 750 species of woody plants, from which Ficus religiosa is one of the Dept. -

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars -****- by Tamarapu Sampath Kumaran About the Author: Mr T Sampath Kumaran is a freelance writer. He regularly contributes articles on Management, Business, Ancient Temples and Temple Architecture to many leading Dailies and Magazines. His articles for the young is very popular in “The Young World section” of THE HINDU. He was associated in the production of two Documentary films on Nava Tirupathi Temples, and Tirukkurungudi Temple in Tamilnadu. His book on “The Path of Ramanuja”, and “The Guide to 108 Divya Desams” in book form on the CD, has been well received in the religious circle. Preface: Tirth Yatras or pilgrimages have been an integral part of Hinduism. Pilgrimages are considered quite important by the ritualistic followers of Sanathana dharma. There are a few centers of sacredness, which are held at high esteem by the ardent devotees who dream to travel and worship God in these holy places. All these holy sites have some mythological significance attached to them. When people go to a temple, they say they go for Darsan – of the image of the presiding deity. The pinnacle act of Hindu worship is to stand in the presence of the deity and to look upon the image so as to see and be seen by the deity and to gain the blessings. There are thousands of Siva sthalams- pilgrimage sites - renowned for their divine images. And it is for the Darsan of these divine images as well the pilgrimage places themselves - which are believed to be the natural places where Gods have dwelled - the pilgrimage is made. -

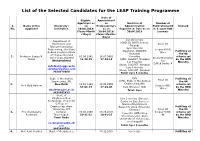

List of the Selected Candidates for the LEAP Training Programme

List of the Selected Candidates for the LEAP Training Programme Date of Eligible Appointment Age/58yrs as as Duration of Number of S. Name of the University / on Professor/8yrs Administrative Publications/30 Remark No. Applicant Institution 30.04.2019/ as on Experience/ 3yrs as on in Scopus-UGC (Years-Month 30.04.2019/ 30.04.2019 Journals s-Days) (Years-Months- Days) 1yr 10 months Department of (HOD, Dr. BATU, Lonere, Electronics and Total: 76 Raigad) Telecommunication 2yrs 8months Engineering, Shri Guru Scopus+UGC: (Registrar, SGGSIET, Fulfilling all Gobind Singhji Institute 30++ Nanded) the 04 of Engineering and 1. Professor Sanjay N. 01.06.1962 16.07.2001 8 months criteria set Technology, Nanded Books/Monograp Talbar 56-10-29 17-09-14 (HOD, SGGSIET, Nanded) by the HRD (Maharashtra) hs/ 1yr 7months Ministry Edited Books: 8 (Dean, SGGSIET, Nanded) [email protected] 1yrs 8 months [email protected] (Dean, SGGSIET, Nanded) 9850978050 Total: 8yrs 5 months Dept. of Mechanical 3yrs Fulfilling all Total: 95 Engineering, JMI, (HOD, Dept. of Mechanical the 04 2. New Delhi 11.02.1962 25.01.2002 Engineering, JMI) criteria set Prof. Abid Haleem Scopus-UGC: 57-02-19 17-03-05 5yrs (Director, IQA) by the HRD 30++ [email protected] Total: 8yrs Ministry 9818501633 Dept. of Pharmaceutical 5yrs 3 months (Director, Technology, University Centre for Excellence in College of NanobioTranslational Engineering, Anna Research, Anna University, Fulfilling all University, BIT Chennai) Total: 96 the 04 3. Prof. Kandasamy Campus, 08.05.1968 05.03.2005 Scopus+UGC: criteria set 5 months (Officiating Ruckmani Tiruchirapalli, 50-11-22 14-01-25 96 by the HRD Vice-Chancellor, Anna Tamil Nadu Ministry University of Technology, Tiruchirapalli) [email protected] u.in Total: 5yrs 8 months 9842484568 4. -

The Third Eye and Pineal Gland Connection

D.U.Quark Volume 5 Issue 1 Fall 2020 Article 2 12-27-2020 Rolling My Third Eye: The Third Eye and Pineal Gland Connection Shannon B. Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/duquark Recommended Citation Jackson, S. B. (2020). Rolling My Third Eye: The Third Eye and Pineal Gland Connection. D.U.Quark, 5 (1). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/duquark/vol5/iss1/2 This Staff Piece is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in D.U.Quark by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. Rolling My Third Eye: The Third Eye and Pineal Gland Connection By Shannon Bow Jackson D.U.Quark 2020. Volume 5 (Issue 1) pgs. 6-13 Published December 27, 2020 Staff Article Chances are the optometrist only checks that two of your eyes are functioning. But what about your third eye; who checks on that? A neurologist? Spiritual Healer? Yoga Instructor? Yourself? The answer might vary, given that this third eye is believed to reside within the pineal gland inside of the brain. The name “third eye” comes from the pineal gland’s primary function of ‘letting in light and darkness’, just as our two eyes do. This gland is the melatonin-secreting neuroendocrine organ containing light-sensitive cells that control the circadian rhythm (1). The diagram shows that nerve cells in the retinas of our eyes allow for light to be sensed. When there is light, the nerve cells in the retina then signal to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus. -

Redalyc.Visiting a Hindu Temple: a Description of a Subjective

Ciencia Ergo Sum ISSN: 1405-0269 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México México Gil-García, J. Ramón; Vasavada, Triparna S. Visiting a Hindu Temple: A Description of a Subjective Experience and Some Preliminary Interpretations Ciencia Ergo Sum, vol. 13, núm. 1, marzo-junio, 2006, pp. 81-89 Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México Toluca, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=10413110 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Visiting a Hindu Temple: A Description of a Subjective Experience and Some Preliminary Interpretations J. Ramón Gil-García* y Triparna S. Vasavada** Recepción: 14 de julio de 2005 Aceptación: 8 de septiembre de 2005 * Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy, Visitando un Templo Hindú: una descripción de la experiencia subjetiva y algunas University at Albany, Universidad Estatal de interpretaciones preliminares Nueva York. Resumen. Académicos de diferentes disciplinas coinciden en que la cultura es un fenómeno Correo electrónico: [email protected] ** Estudiante del Doctorado en Administración complejo y su comprensión requiere de un análisis detallado. La complejidad inherente al y Políticas Públicas en el Rockefeller College of estudio de patrones culturales y otras estructuras sociales no se deriva de su rareza en la Public Affairs and Policy, University at Albany, sociedad. De hecho, están contenidas y representadas en eventos y artefactos de la vida cotidiana. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Sri Chakra the Source of the Cosmos

Sri Chakra The Source of the Cosmos The Journal of the Sri Rajarajeswari Peetam, Rush, NY Blossom 23 Petal 4 December 2018 Blossom 23, Petal 4 I Temple Bulletin 3 N Past Temple Events 4 T Upcoming Temple H Events 6 I 2019 Pocket NEW! S Calender 7 Steps Towards Our I Granite Temple 8 S S Aiya’s Vision 9 U What does Japam do? 11 E The Vedic Grove 13 The Science of the Breath 16 Ganaamritam 18 Gurus, Saints & Sages 22 Naivēdyam Nivēdayāmi 27 Kids Korner! 30 2 Sri Rajarajeswari Peetam • 6980 East River Road • Rush, NY 14543 • Phone: (585) 533 - 1970 Sri Chakra ● December 2018 TEMPLETEMPLETEMPLE BULLETINBULLETINBULLETIN Rajagopuram Project Temple Links Private Homa/Puja Booking: As many of you know, Aiya has been speaking about the need for a more permanent srividya.org/puja sacred home for Devi for a number of years. Over the past 40 years, the Temple has evolved into an important center for the worship of the Divine Mother Rajagopuram Project (Granite Rajarajeswari, attracting thousands of visitors each year from around the world. Temple): It is now time to take the next step in fulfilling Aiya’s vision of constructingan srividya.org/rajagopuram Agamic temple in granite complete with a traditional Rajagopuram. With the grace of the Guru lineage and the loving blessings of our Divine Mother, now is Email Subscriptions: the right time to actively participate and contribute to make this vision a reality. srividya.org/email The new Temple will be larger and will be built according to the Kashyapa Temple Timings: Shilpa Shastra.