UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siddheshwari Devi Final Edit Rev 1

Siddheshwari Devi – The Queen of Thumri1 by Aditi Desai Kashi, Benares or Varanasi; the ancient spiritual centre of Hindustan, famous for its Ganga, its temples and ghats, pandits and pandas, had another more sensual side in its graceful yet throbbing sub-culture of music and dance. There was a time when for every devotee going to a temple to propitiate the gods there was another who, chewing his delicately flavoured paan, 1 Edited, updated and rewritten version based on: Original article written by Aditi Desai for The India Magazine, Aug. 1981, No. 9 would be strolling towards some singer’s or dancer’s house. In the Benares sunset, the sound of temple bells intermingled with the soul stirring sounds of a bhajan, a thumri, a kajri, a chaiti, a hori. And accompanying these were the melodious sounds of the sarangi or flute and the ghunghroos on the beat of the tabla that quickened the heartbeat. So great was the city’s preoccupation with music, that a distinctive style of classical music, rooted in the local folk culture, emerged and was embodied in the Benaras Gharana ( school or a distinctive style of music originating in a family tradition or lineage that can be traced to an instructor or region). A few miles from Benares, there is a village called Torvan, which appears to be like any other Thakur Brahmin village of that region. But there is a difference. This village had a few families belonging to the Gandharva Jati, a group whose traditional occupation was music and its allied arts. Amongst Gandharvas, it was the men who went out to perform while the women stayed behind. -

The Guru: by Various Authors

Divya Darshan Contributors; Publisher Pt Narayan Bhatt Guru Purnima: Hindu Heritage Society ABN 60486249887 Smt Lalita Singh Sanskriti Divas Medley Avenue Liverpool NSW 2170 Issue Pt Jagdish Maharaj Na tu mam shakyase drashtumanenaiv svachakshusha I Divyam dadami te chakshu pashay me yogameshwaram Your external eyes will not be able to comprehend my Divine form. I grant you the Divine Eye to enable you to This issue includes; behold Me in my Divine Yoga. Gita Chapter 11. Guru Mahima Guru Purnima or Sanskriti Diwas Krishnam Vande Jagad Gurum The Guru: by various Authors Message of the Guru Teaching of Raman Maharshi Guru and Disciple Hindu Sects Non Hindu Sects The Greatness of the Guru Prayer of Guru Next Issue Sri Krishna – The Guru of All Gurus VASUDEV SUTAM DEVAM KANSA CHANUR MARDAMAN DEVKI PARAMAANANDAM KRISHANAM VANDE JAGADGURUM I do vandana (glorification) of Lord Krishna, the resplendent son of Vasudev, who killed the great tormentors like Kamsa and Chanoora, who is a source of greatest joy to Devaki, and who is indeed a Jagad Guru (world teacher). 1 | P a g e Guru Mahima Sab Dharti Kagaz Karu, Lekhan Ban Raye Sath Samundra Ki Mas Karu Guru Gun Likha Na Jaye ~ Kabir This beautiful doha (couplet) is by the great saint Kabir. The meaning of this doha is “Even if the whole earth is transformed into paper with all the big trees made into pens and if the entire water in the seven oceans are transformed into writing ink, even then the glories of the Guru cannot be written. So much is the greatness of the Guru.” Guru means a teacher, master, mentor etc. -

Contemporary Art in Indian Context

Artistic Narration, Vol. IX, 2018, No. 2: ISSN (P) : 0976-7444 (e) : 2395-7247Impact Factor 6.133 (SJIF) Contemporary Art in Indian Context Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai Richa Singh Asso. Prof., Research Scholar Deptt. of Drawing & Painting M.F.A. M.M.H. College B.Ed. Ghaziabad, U.P. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Abstract: This article has a focus on Contemporary Art in Indian context. Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai Through this article emphasizesupon understanding the changes in Richa Singh, Contemporary Art over a period of time in India right from its evolution to the economic liberalization period than in 1990’s and finally in the Contemporary Art in current 21st century. The article also gives an insight into the various Indian Context, techniques and methods adopted by Indian Contemporary Artists over a period of time and how the different generations of artists adopted different techniques in different genres. Finally the article also gives an insight Artistic Narration 2018, into the current scenario of Indian Contemporary Art and the Vol. IX, No.2, pp.35-39 Contemporary Artists reach to the world economy over a period of time. key words: Contemporary Art, Contemporary Artists, Indian Art, 21st http://anubooks.com/ Century Art, Modern Day Art ?page_id=485 35 Contemporary Art in Indian Context Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai, Richa Singh Contemporary Art Contemporary Art refers to art – namely, painting, sculpture, photography, installation, performance and video art- produced today. Though seemingly simple, the details surrounding this definition are often a bit fuzzy, as different individuals’ interpretations of “today” may widely vary. -

Indian Classical Dance Is a Relatively New Umbrella Term for Various Codified Art Forms Rooted in Natya, the Sacred Hindu Musica

CLASSICAL AND FOLK DANCES IN INDIAN CULTURE Palkalai Chemmal Dr ANANDA BALAYOGI BHAVANANI Chairman: Yoganjali Natyalayam, Pondicherry. INTRODUCTION: Dance in India comprises the varied styles of dances and as with other aspects of Indian culture, different forms of dances originated in different parts of India, developed according to the local traditions and also imbibed elements from other parts of the country. These dance forms emerged from Indian traditions, epics and mythology. Sangeet Natak Akademi, the national academy for performing arts, recognizes eight distinctive traditional dances as Indian classical dances, which might have origin in religious activities of distant past. These are: Bharatanatyam- Tamil Nadu Kathak- Uttar Pradesh Kathakali- Kerala Kuchipudi- Andhra Pradesh Manipuri-Manipur Mohiniyattam-Kerala Odissi-Odisha Sattriya-Assam Folk dances are numerous in number and style, and vary according to the local tradition of the respective state, ethnic or geographic regions. Contemporary dances include refined and experimental fusions of classical, folk and Western forms. Dancing traditions of India have influence not only over the dances in the whole of South Asia, but on the dancing forms of South East Asia as well. In modern times, the presentation of Indian dance styles in films (Bollywood dancing) has exposed the range of dance in India to a global audience. In ancient India, dance was usually a functional activity dedicated to worship, entertainment or leisure. Dancers usually performed in temples, on festive occasions and seasonal harvests. Dance was performed on a regular basis before deities as a form of worship. Even in modern India, deities are invoked through religious folk dance forms from ancient times. -

Mid Wales Llanidloes

This document is a snapshot of content from a discontinued BBC website, originally published between 2002-2011. It has been made available for archival & research purposes only. Please see the foot of this document for Archive Terms of Use. 4 May 2012 Accessibility help Text only BBC Homepage Wales Home Archer's Actor - Jamila Massey more from this section Last updated: 03 August 2006 Llanidloes The actor Jamila Massey is Archer's Actor - Jamila Massey Chartist Revolt famous for her role as Auntie Claims to Fame Satya in Radio 4 's daily Clywedog Dam Clywedog Sailing Club BBC Local agricultural sopa opera the Archers. She has lived in Going Solar Mid Wales Great Outdoors Festival 2007 Llanidloes for nearly twenty Things to do Info Centres years. Read on to find out Llani Car Club People & Places more about her life and work. Llanidloes Museum Nature & Outdoors My Town History Outside Looking In Phototour Religion & Ethics How did you get into acting? Rotary Across Wales Walk Arts & Culture Sport Centre Fun Day Music I came to the UK with my parents in 1946. After the war, my Timber-Framed Buildings TV & Radio father didn't want to be in the army anymore and he applied to the BBC and got a producer's job at 200 Oxford Street. Local BBC Sites The studios were later moved to Bush House. He was that News rare commodity - a born broadcaster - and, I suspect, some Sport of that rubbed off on to me. Weather Travel At that time, there were few Asians in this country and Neighbouring Sites certainly very few Asian children. -

Godrej Consumer Products Limited

GODREJ CONSUMER PRODUCTS LIMITED List of shareholders in respect of whom dividend for the last seven consective years remains unpaid/unclaimed The Unclaimed Dividend amounts below for each shareholder is the sum of all Unclaimed Dividends for the period Nov 2009 to May 2016 of the respective shareholder. The equity shares held by each shareholder is as on Nov 11, 2016 Sr.No Folio Name of the Shareholder Address Number of Equity Total Dividend Amount shares due for remaining unclaimed (Rs.) transfer to IEPF 1 0024910 ROOP KISHORE SHAKERVA I R CONSTRUCTION CO LTD P O BOX # 3766 DAMMAM SAUDI ARABIA 180 6,120.00 2 0025470 JANAKIRAMA RAMAMURTHY KASSEMDARWISHFAKROO & SONS PO BOX 3898 DOHA QATAR 240 8,160.00 3 0025472 NARESH KUMAR MAHAJAN 176 HIGHLAND MEADOW CIRCLE COPPELL TEXAS U S A 240 8,160.00 4 0025645 KAPUR CHAND GUPTA C/O PT SOUTH PAC IFIC VISCOSE PB 11 PURWAKARTA WEST JAWA INDONESIA 360 12,240.00 5 0025925 JAGDISHCHANDRA SHUKLA C/O GEN ELECTRONICS & TDG CO PO BOX 4092 RUWI SULTANATE OF OMAN 240 8,160.00 6 0027324 HARISH KUMAR ARORA 24 STONEMOUNT TRAIL BRAMPTON ONTARIO CANADA L6R OR1 360 12,240.00 7 0028652 SANJAY VARNE SSB TOYOTA DIVI PO BOX 6168 RUWI AUDIT DEPT MUSCAT S OF OMAN 60 2,040.00 8 0028930 MOHAMMED HUSSAIN P A LEBANESE DAIRY COMPANY POST BOX NO 1079 AJMAN U A E 120 4,080.00 9 K006217 K C SAMUEL P O BOX 1956 AL JUBAIL 31951 KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA 180 6,120.00 10 0001965 NIRMAL KUMAR JAIN DEP OF REVENUE [INCOMETAX] OFFICE OF THE TAX RECOVERY OFFICER 4 15/295A VAIBHAV 120 4,080.00 BHAWAN CIVIL LINES KANPUR 11 0005572 PRAVEEN -

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

List of Candidates Who Have Not Submitted Their Neet Ug 2017 Roll Number

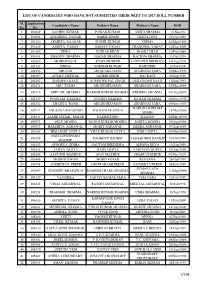

LIST OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE NOT SUBMITTED THEIR NEET UG 2017 ROLL NUMBER Sl. Application Candidate's Name Father's Name Mother's Name DOB No. No. 1 100249 SACHIN KUMAR PAWAN KUMAR ANITA SHARMA 15.Nov.93 2 100808 ANUSHEEL NAGAR OMBIR SINGH GEETA DEVI 07/Oct/1998 3 101222 AKSHITA DAAGAR SUSHIL KUMAR SEEMA 24/May/1999 4 101469 ANKITA YADAV SANJAY YADAV CHANCHAL YADAV 31/Dec/1999 5 101593 ZEWA NAWAB KHAN NOOR JAHAN 10/Feb/1999 6 101814 SHAGUN SHARMA GAGAN SHARMA RACHNA SHARMA 13/Oct/1998 7 102087 MOHD FAISAL SHAHABUDDIN JANNATUL FIRDOUS 14/Aug/1998 8 102121 SNEHA SOBODH KUMAR RAJENDRI 20/Jul/1998 9 102256 ABUZAR MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 25/Mar/1999 10 102397 ANJALI DESWAL JAGBIR SINGH RAJ RANI 05/Sep/1998 11 102402 RASMEET KAUR SURINDER PAL SINGH GURVINDER KAUR 11/Sep/1997 12 102474 ABU TALHA MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 25/Mar/1999 13 102515 SHIVANI SHARMA RAKESH KUMAR SHARMA KRISHNA SHARMA 01/Aug/2000 14 102529 POONAM SHARMA GOVIND SHARMA RAJESH SHARMA 04/Nov/1998 15 102532 SHAISTA BANO MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 09/Nov/1997 KARUNA KUMARI 16 102711 ANUSHKA RAJ SINGH RAJ KUMAR SINGH 12/Mar/2000 SINGH 17 102841 AAMIR SUHAIL MALIK NASIMUDDIN SHANNO 26/May/1996 18 102971 ABLE MOGHA MANOJ KUMAR MOGHA SARITA MOGHA 19/Aug/1998 19 103053 HARSHITA AGRAWAL MOHIT AGRAWAL MEERA AGRAWAL 07/Sep/1999 20 103245 HIMANSHI GUPTA VIJAY KUMAR GUPTA INDU GUPTA 09/May/2000 NGULLIENTHANG 21 103428 PAOKHUP HAOKIP VANKHOMOI HAOKIP 03/Oct/1998 HAOKIP 22 103433 APOORVA SINHA GAUTAM BIRENDRA ALPANA DEVA 12/Sep/1999 23 103518 TANYA GUPTA RAJIV GUPTA VANDANA GUPTA 29/Apr/1999 -

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 9, Issue 12 December, 2015

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 9, Issue 12 December, 2015 HARI OM In Month of November, many activities were performed in temple and many devotees attended various programs. Sri Balaji Guru Vandana was celebrated grandly with 108 kalasha Ganapathi abhishekam, 108 kalasha Balaji abhishekam, Mahalakshmi abhishekam and Sathya Narayana Pooja. On Friday 20th November, 108 kalasha sthapana (presenting to God) for Balaji abhishekam was done. Families sat individually and invoked almighty lord doing sankalpa (resolution) and performed Ganapthi, Navagraha Poojas and Mahalakshmi abhishekam. Pitathipathi Sri Narayananada Swamiji initiated and led all the devotees in reciting mantras. Later, everyone was enchanted with the Mahalakshi abhishekam. Vittal Nithyananda Swami spoke about the meaning of Guru (Teacher). He talked about how the temple has grown today since the 2006 Charasthapatha of Balaji into a spacious place where devotees can come to feel one with God anytime and also how the Balaji Guru Vandana has become such a grand event every year. He Sri Balaji Guru Vandana, Swamiji talked of how Swamiji had a vision of Lord Balaji and how that vision has Praying to lord Sri Satyanarayana for devotes turned into a reality by which devotees are all able to come here to see and and world peace. pray to all the gods and goddesses. By performing Guru Vandana, devotees can feel closer to God and through performing the poojas, all their doshas (problems) are removed. Later, Mahaprasadam sponsored by Peacock sreyo hi jnanam abhyasaj jnanad dhyanam visisyate | Cupertino (Sri Ram Gopal) was served to everyone. dhyanat karma-phala-tyagas tyagac chantir anantaram || On Saturday 21st November, 108 kalasha abhisheka was performed to invoke Lord Balaji and Swamiji performed this abhisheka with help from other priest’s and devotees. -

The Modes of Representation of Faces in South Asian Painting

<Research Notes>Profiled Figures: The Modes of Title Representation of Faces in South Asian Painting Author(s) IKEDA, Atsushi イスラーム世界研究 : Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies Citation (2017), 10: 67-82 Issue Date 2017-03-20 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/225230 ©京都大学大学院アジア・アフリカ地域研究研究科附属 Right イスラーム地域研究センター 2017 Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University イスラーム世界研究 第 10 巻(2017 年 3 月)67‒82 頁 Profiled Figures Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies, 10 (March 2017), pp. 67–82 Profiled Figures: The Modes of Representation of Faces in South Asian Painting IKEDA Atsushi* Introduction This paper argues that South Asian people’s physical features such as eye and nose prompted Hindu painters to render figures in profile in the late medieval and early modern periods. In addition, I would like to explore the conceptual and theological meanings of each mode i.e. the three quarter face, the profile view, and the frontal view from both Islamic and Hindu perspectives in order to find out the reasons why Mughal painters adopted the profile as their artistic standard during the reign of Jahangīr (1605–27). Various facial modes characterized South Asian paintings at each period. Perhaps the most important example of paintings in South Asia dates from B.C. 1 to A.C. 5 century and is located in the Ajantā cave in India. It depicts Buddhist ascetics in frontal view, while other figures are depicted in three quarter face with their eyes contained within the line that forms the outer edge (Figure 1). Moving to the Ellora cave paintings executed between the 5th and 7th century, some figures show the eye in the far side pushed out of the facial line. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Indian Dance Drama Tradition

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-3, Issue-4, 2017 (Special Issue), ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in Proceedings of 5th International Conference on Recent Trends in Science Technology, Management and Society Indian Dance Drama Tradition Dr. Geetha B V Post-Doctoral research fellow, Women Studies Department, Kuvempu University, Shankarghatta, Shimoga. Abstract: In the cultures of the Indian subcontinent, for its large, elaborate make up and costumes. The drama and ritual have been integral parts of a elaborate costumes of Kathakalli become the most single whole from earliest recorded history. The recognized icon of Kerala. The themes of the first evidences of ritual dance drama performances Kathakali are religious in nature. The typically occur in the rock painting of Mirzapur, Bhimbetka, deal with the Mahabarat, the Ramayana and the and in other sites, which are various dated 20,000- ancient Scriptures known as the puranas. 5000 bce. The ancient remains of Mohenjo-Daro Kuchipudi dance drama traditions hails from and the Harappa (2500-2000 bce) are more Andhrapradesh. BhamaKalapam is the most definitive. Here archeological remains clearly popular Dance-Drama in Kuchipudi repertoire point to the prevalence of ritual performance ascribed to Siddhendra Yogi. The story revolves involving populace and patrons. The Mohenjo – round the quarrel between satyabhama and Daro seals, bronze fegurines, and images of priest Krishna. and broken torsos are all clear indications of dance In this paper I am dealing with Yakshagana dance as ritual. The aspects of vedic ritual tradition drama tradition. I would like to discuss this art closest to dance and drama was a rigorous system form’s present scenario.