Crayfishes and Shrimps) of Arkansas with a Discussion of Their Ah Bitats Raymond W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Alien Crayfish Species in Central Europe

NEW ALIEN CRAYFISH SPECIES IN CENTRAL EUROPE Introduction pathways, life histories, and ecological impacts DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades Dr. rer. nat. der Fakultät für Naturwissenschaften der Universität Ulm vorgelegt von Christoph Chucholl aus Rosenheim Ulm 2012 NEW ALIEN CRAYFISH SPECIES IN CENTRAL EUROPE Introduction pathways, life histories, and ecological impacts DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades Dr. rer. nat. der Fakultät für Naturwissenschaften der Universität Ulm vorgelegt von Christoph Chucholl aus Rosenheim Ulm 2012 Amtierender Dekan: Prof. Dr. Axel Groß Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Manfred Ayasse Zweitgutachter: Prof. apl. Dr. Gerhard Maier Tag der Prüfung: 16.7.2012 Cover picture: Orconectes immunis male (blue color morph) (photo courtesy of Dr. H. Bellmann) Table of contents Part 1 – Summary Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 Invasive alien species – a global menace ....................................................................... 1 “Invasive” matters .......................................................................................................... 2 Crustaceans – successful invaders .................................................................................. 4 The case of alien crayfish in Europe .............................................................................. 5 New versus Old alien crayfish ....................................................................................... -

Decapod Crustacean Grooming: Functional Morphology, Adaptive Value, and Phylogenetic Significance

Decapod crustacean grooming: Functional morphology, adaptive value, and phylogenetic significance N RAYMOND T.BAUER Center for Crustacean Research, University of Southwestern Louisiana, USA ABSTRACT Grooming behavior is well developed in many decapod crustaceans. Antennular grooming by the third maxillipedes is found throughout the Decapoda. Gill cleaning mechanisms are qaite variable: chelipede brushes, setiferous epipods, epipod-setobranch systems. However, microstructure of gill cleaning setae, which are equipped with digitate scale setules, is quite conservative. General body grooming, performed by serrate setal brushes on chelipedes and/or posterior pereiopods, is best developed in decapods at a natant grade of body morphology. Brachyuran crabs exhibit less body grooming and virtually no specialized body grooming structures. It is hypothesized that the fouling pressures for body grooming are more severe in natant than in replant decapods. Epizoic fouling, particularly microbial fouling, and sediment fouling have been shown r I m ans of amputation experiments to produce severe effects on olfactory hairs, gills, and i.icubated embryos within short lime periods. Grooming has been strongly suggested as an important factor in the coevolution of a rhizocephalan parasite and its anomuran host. The behavioral organization of grooming is poorly studied; the nature of stimuli promoting grooming is not understood. Grooming characters may contribute to an understanding of certain aspects of decapod phylogeny. The occurrence of specialized antennal grooming brushes in the Stenopodidea, Caridea, and Dendrobranchiata is probably not due to convergence; alternative hypotheses are proposed to explain the distribution of this grooming character. Gill cleaning and general body grooming characters support a thalassinidean origin of the Anomura; the hypothesis of brachyuran monophyly is supported by the conservative and unique gill-cleaning method of the group. -

Palaemonetes Kadiakensis Rathbun: Post Embryonic Growth in the Laboratory (Decapoda, Palaemonidae)

PALAEMONETES KADIAKENSIS RATHBUN: POST EMBRYONIC GROWTH IN THE LABORATORY (DECAPODA, PALAEMONIDAE) BY JERRY H. HUBSCHMAN and JO ANN ROSE Department of Biology, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio 45431, U.S.A. and Franz Theodore Stone Laboratory, Put In Bay, Ohio, U.S.A. INTRODUCTION The study of larval development in decapod Crustacea has become continually refined during the past decade. Historically, the descriptive phases of larval development of marine decapods has been based upon the study of series collected in the plankton. In time, a wide range of species representing a number of decapod orders have been reared from egg to metamorphosis in the laboratory. As a result of this work, much of the variation in size and form observed in the plankton material has also been demonstrable in the laboratory. Five species of Eastern U.S. Palaemonete.r have been reared successfully through metamorphosis in the laboratory. These represent three marine forms: Palaemonete.r vulgaris (Say) and P. pugio Holthuis by Broad (1957a, b) and P. intermedius Holthuis by Broad & Hubschman (1962); and two freshwater species: Palaemonete.r k.adiaken.ri.r Rath- bun by Broad & Hubschman (1960, 1963) and P. paludo.ru.r (Gibbes) by Dobkin (1963). Broad ( 1957b) has demonstrated variation in molting frequency and duration of larval life as a function of diet. It is apparent that the sequence of morpholo- gical and physiological changes leading to metamorphosis bears no direct relation- ship to molting history. Indeed, the control mechanisms involved in both larval processes are not known. In adult shrimp, the initiation of molting is mediated by eyestalk hormones. -

Estimating the Threat Posed by the Crayfish Plague Agent

Estimating the threat posed by the crayfish plague agent Aphanomyces astaci to crayfish species of Europe and North America — Introduction pathways, distribution and genetic diversity by Jörn Panteleit from Aachen, Germany Accepted Dissertation thesis for the partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctor of Natural Sciences Fachbereich 7: Natur- und Umweltwissenschaften Universität Koblenz-Landau Thesis examiners: Prof. Dr. Ralf Schulz, University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany Dr. Japo Jussila, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Suomi-Finland Date of oral examination: January 17th, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. LIST OF PUBLICATIONS ........................................................................................................................ 3 2. ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Zusammenfassung ......................................................................................................................... 5 3. ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................................. 6 4. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 7 4.1 Invasive species ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.2 Freshwater crayfish in Europe ...................................................................................................... -

Decapoda: Cambaridae) of Arkansas Henry W

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 71 Article 9 2017 An Annotated Checklist of the Crayfishes (Decapoda: Cambaridae) of Arkansas Henry W. Robison Retired, [email protected] Keith A. Crandall George Washington University, [email protected] Chris T. McAllister Eastern Oklahoma State College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Biology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Robison, Henry W.; Crandall, Keith A.; and McAllister, Chris T. (2017) "An Annotated Checklist of the Crayfishes (Decapoda: Cambaridae) of Arkansas," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 71 , Article 9. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol71/iss1/9 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. An Annotated Checklist of the Crayfishes (Decapoda: Cambaridae) of Arkansas Cover Page Footnote Our deepest thanks go to HWR’s numerous former SAU students who traveled with him in search of crayfishes on many fieldtrips throughout Arkansas from 1971 to 2008. Personnel especially integral to this study were C. -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Checklist of the Crayfish and Freshwater Shrimp (Decapoda) of Indiana

2001. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 110:104-110 CHECKLIST OF THE CRAYFISH AND FRESHWATER SHRIMP (DECAPODA) OF INDIANA Thomas P. Simon: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 620 South Walker Street, Bloomington, Indiana 47401 ABSTRACT. Crayfish and freshwater shrimp are members of the order Decapoda. All crayfish in In- diana are members of the family Cambaridae, while the freshwater shrimp belong to Palaemonidae. Two genera of freshwater shrimps, each represented by a single species, occur in Indiana. Palaemonetes ka- diakensis and Macrobrachium ohione are lowland forms. Macrobrachium ohione occurs in the Ohio River drainage, while P. kadiakensis occurs statewide in wetlands and lowland areas including inland lakes. Currently, 21 crayfish taxa, including an undescribed form of Cambarus diogenes, are found in Indiana. Another two species are considered hypothetical in occurrence. Conservation status is recommended for the Ohio shrimp Macrobrachium ohione, Indiana crayfish Orconectes indianensis, and both forms of the cave crayfish Orconectes biennis inennis and O. i. testii. Keywords: Cambaridae, Palaemonidae, conservation, ecology The crayfish and freshwater shrimp belong- fish is based on collections between 1990 and ing to the order Decapoda are among the larg- 2000. Collections were made at over 3000 lo- est of Indiana's aquatic invertebrates. Crayfish calities statewide, made in every county of the possess five pair of periopods, the first is mod- state, but most heavily concentrated in south- ified into a large chela and dactyl (Pennak ern Indiana, where the greatest diversity of 1978; Hobbs 1989). The North American species occurs. families, crayfish belong to two Astacidae and The current list of species is intended to Cambaridae with all members east of the Mis- provide a record of the extant and those ex- sissippi River belong to the family Cambari- tirpated from the fauna of Indiana over the last dae (Hobbs 1974a). -

Development of Tolerance Values for Kentucky Crayfishes

Development of Tolerance Values for Kentucky Crayfishes Kentucky Environmental and Public Protection Cabinet Department for Environmental Protection Division of Water Water Quality Branch Watershed Management Branch 2004 Cover photograph description: Cambarus dubius, Morgan County, Kentucky Suggested Citation: Peake, D.R., G.J. Pond, and S.E. McMurray. 2004. Development of tolerance values for Kentucky crayfishes. Kentucky Environmental and Public Protection Cabinet, Department for Environmental Protection, Division of Water, Frankfort. The Environmental and Public Protection Cabinet (EPPC) does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, religion, or disability. The EPPC will provide, on request, reasonable accommodations including auxiliary aids and services necessary to afford an individual with a disability an equal opportunity to participate in all services, programs and activities. To request materials in an alternative format, contact the Kentucky Division of Water, 14 Reilly Road, Frankfort, KY, 40601 or call (502) 564-3410. Hearing and speech-impaired persons can contact the agency by using the Kentucky Relay Service, a toll-free telecommunications device for the deaf (TDD). For voice to TDD, call 800-648- 6057. For TDD to voice, call 800-648-6056. Funding for this project was provided in part by a grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) to the Kentucky Division of Water, Nonpoint Source Section, as authorized by the Clean Water Act Amendments of 1987, §319(h) Nonpoint Source Implementation Grant # C9994861-01. Mention of trade names or commercial products, if any, does not constitute endorsement. This document was printed on recycled paper. Development of Tolerance Values for Kentucky Crayfishes By Daniel R. -

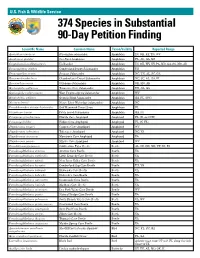

374 Species in Substantial 90-Day Petition Finding

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 374 Species in Substantial 90-Day Petition Finding Scientific Name Common Name Taxon/Validity Reported Range Ambystoma barbouri Streamside salamander Amphibian IN, OH, KY, TN, WV Amphiuma pholeter One-Toed Amphiuma Amphibian FL, AL, GA, MS Cryptobranchus alleganiensis Hellbender Amphibian IN, OH, WV, NY, PA, MD, GA, SC, MO, AR Desmognathus abditus Cumberland Dusky Salamander Amphibian TN Desmognathus aeneus Seepage Salamander Amphibian NC, TN, AL, SC, GA Eurycea chamberlaini Chamberlain's Dwarf Salamander Amphibian NC, SC, AL, GA, FL Eurycea tynerensis Oklahoma Salamander Amphibian OK, MO, AR Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander Amphibian TN, AL, GA Gyrinophilus subterraneus West Virginia Spring Salamander Amphibian WV Haideotriton wallacei Georgia Blind Salamander Amphibian GA, FL (NW) Necturus lewisi Neuse River Waterdog (salamander) Amphibian NC Pseudobranchus striatus lustricolus Gulf Hammock Dwarf Siren Amphibian FL Urspelerpes brucei Patch-nosed Salamander Amphibian GA, SC Crangonyx grandimanus Florida Cave Amphipod Amphipod FL (N. and NW) Crangonyx hobbsi Hobb's Cave Amphipod Amphipod FL (N. FL) Stygobromus cooperi Cooper's Cave Amphipod Amphipod WV Stygobromus indentatus Tidewater Amphipod Amphipod NC, VA Stygobromus morrisoni Morrison's Cave Amphipod Amphipod VA Stygobromus parvus Minute Cave Amphipod Amphipod WV Cicindela marginipennis Cobblestone Tiger Beetle Beetle AL, IN, OH, NH, VT, NJ, PA Pseudanophthalmus avernus Avernus Cave Beetle Beetle VA Pseudanophthalmus cordicollis Little -

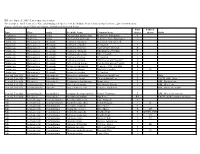

Threatened and Endangered Species List

Effective April 15, 2009 - List is subject to revision For a complete list of Tennessee's Rare and Endangered Species, visit the Natural Areas website at http://tennessee.gov/environment/na/ Aquatic and Semi-aquatic Plants and Aquatic Animals with Protected Status State Federal Type Class Order Scientific Name Common Name Status Status Habit Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus gulolineatus Berry Cave Salamander T Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus bouchardi Big South Fork Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus cymatilis A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus deweesae Valley Flame Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus extraneus Chickamauga Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus obeyensis Obey Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus pristinus A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus williami "Brawley's Fork Crayfish" E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Fallicambarus hortoni Hatchie Burrowing Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes incomptus Tennessee Cave Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes shoupi Nashville Crayfish E LE Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes wrighti A Crayfish E Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris carthusiana Spinulose Shield Fern T Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris cristata Crested Shield-Fern T FACW, OBL, Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Trichomanes boschianum -

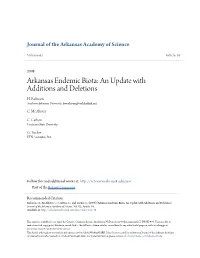

Arkansas Endemic Biota: an Update with Additions and Deletions H

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 62 Article 14 2008 Arkansas Endemic Biota: An Update with Additions and Deletions H. Robison Southern Arkansas University, [email protected] C. McAllister C. Carlton Louisiana State University G. Tucker FTN Associates, Ltd. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Robison, H.; McAllister, C.; Carlton, C.; and Tucker, G. (2008) "Arkansas Endemic Biota: An Update with Additions and Deletions," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 62 , Article 14. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol62/iss1/14 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 62 [2008], Art. 14 The Arkansas Endemic Biota: An Update with Additions and Deletions H. Robison1, C. McAllister2, C. Carlton3, and G. Tucker4 1Department of Biological Sciences, Southern Arkansas University, Magnolia, AR 71754-9354 2RapidWrite, 102 Brown Street, Hot Springs National Park, AR 71913 3Department of Entomology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803-1710 4FTN Associates, Ltd., 3 Innwood Circle, Suite 220, Little Rock, AR 72211 1Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Pringle and Witsell (2005) described this new species of rose-gentian from Saline County glades. -

At-Risk Species Assessment on Southern National Forests, Refuges, and Other Protected Areas

David Moynahan | St. Marks NWR At-Risk Species Assessment on Southern National Forests, Refuges, and Other Protected Areas National Wildlife Refuge Association Mark Sowers, Editor October 2017 1001 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 905, Washington, DC 20036 • 202-417-3803 • www.refugeassociation.org At-Risk Species Assessment on Southern National Forests, Refuges, and Other Protected Areas Table of Contents Introduction and Methods ................................................................................................3 Results and Discussion ......................................................................................................9 Suites of Species: Occurrences and Habitat Management ...........................................12 Progress and Next Steps .................................................................................................13 Appendix I: Suites of Species ..........................................................................................17 Florida Panhandle ............................................................................................................................18 Peninsular Florida .............................................................................................................................28 Southern Blue Ridge and Southern Ridge and Valley ...............................................................................................................................39 Interior Low Plateau and Cumberland Plateau, Central Ridge and Valley ...............................................................................................46