South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanoreceptors in Early Developmental Stages of the Pycnogonida

UACE2019 - Conference Proceedings Mechanoreceptors in Early Developmental Stages of the Pycnogonida John A. Fornshell * a a U.S. National Museum of Natural History Department of Invertebrate Zoology Smithsonian Institution Washington, D.C. USA *Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel. (571) 426-2398 ABSTRACT Members of the phylum Arthropoda detect fluid flow and sound/particle vibrations using sensory organs called sensilla. These sensilla detect sound/particle vibrations in the boundary layer. In the present study, archived specimens from the United States National Museum of Natural History were examined in an effort to extend our knowledge of the presence of sensilla on the early post hatching developmental stages, first and second instars, of pycnogonids. In the work presented here we look at three families, four genera and ten species of early post hatching developmental stages of sea spiders. They are Family Ammotheidae, Achelia cuneatis Child, 1999, Ammothea allopodes Fry and Hedgpeth, 1969, Ammothea carolinensis Leach 1814, Ammothea clausi Pfeffer, 1889, Ammothea striata (Möbius, 1902), Family Nymphonidae, Nymphon grossipes (Fabricius, 1780), N. australe Hodgson, 1902, N. charcoti Bouvier, 1911, N. Tenellum (Sars, 1888) and Pycnogonidae, Pentapycnon charcoti Bouvier, 1910. Electron micrograph images of these species were used to identify and describe the sensilla present. Most body organs such as mouthparts, the eye tubercle, appendages and spines are proportionally much smaller in the early post hatching developmental stages compared to their size in the adults, while the sensilla are comparable in size and shape to those found on the adults. In the first instar of Pentapycnon charcoti sensilla are present, but not in the adult. -

Unali'yi Lodge

Unali’Yi Lodge 236 Table of Contents Letter for Our Lodge Chief ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Letter from the Editor ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Local Parks and Camping ...................................................................................................................................... 9 James Island County Park ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Palmetto Island County Park ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Wannamaker County Park ............................................................................................................................................. 13 South Carolina State Parks ................................................................................................................................. 14 Aiken State Park ................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Andrew Jackson State Park ........................................................................................................................................... -

Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean Volume

ISBN 0-9689167-4-x Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean (Davis Strait, Southern Greenland and Flemish Cap to Cape Hatteras) Volume One Acipenseriformes through Syngnathiformes Michael P. Fahay ii Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean iii Dedication This monograph is dedicated to those highly skilled larval fish illustrators whose talents and efforts have greatly facilitated the study of fish ontogeny. The works of many of those fine illustrators grace these pages. iv Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean v Preface The contents of this monograph are a revision and update of an earlier atlas describing the eggs and larvae of western Atlantic marine fishes occurring between the Scotian Shelf and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina (Fahay, 1983). The three-fold increase in the total num- ber of species covered in the current compilation is the result of both a larger study area and a recent increase in published ontogenetic studies of fishes by many authors and students of the morphology of early stages of marine fishes. It is a tribute to the efforts of those authors that the ontogeny of greater than 70% of species known from the western North Atlantic Ocean is now well described. Michael Fahay 241 Sabino Road West Bath, Maine 04530 U.S.A. vi Acknowledgements I greatly appreciate the help provided by a number of very knowledgeable friends and colleagues dur- ing the preparation of this monograph. Jon Hare undertook a painstakingly critical review of the entire monograph, corrected omissions, inconsistencies, and errors of fact, and made suggestions which markedly improved its organization and presentation. -

Diversity of Norwegian Sea Slugs (Nudibranchia): New Species to Norwegian Coastal Waters and New Data on Distribution of Rare Species

Fauna norvegica 2013 Vol. 32: 45-52. ISSN: 1502-4873 Diversity of Norwegian sea slugs (Nudibranchia): new species to Norwegian coastal waters and new data on distribution of rare species Jussi Evertsen1 and Torkild Bakken1 Evertsen J, Bakken T. 2013. Diversity of Norwegian sea slugs (Nudibranchia): new species to Norwegian coastal waters and new data on distribution of rare species. Fauna norvegica 32: 45-52. A total of 5 nudibranch species are reported from the Norwegian coast for the first time (Doridoxa ingolfiana, Goniodoris castanea, Onchidoris sparsa, Eubranchus rupium and Proctonotus mucro- niferus). In addition 10 species that can be considered rare in Norwegian waters are presented with new information (Lophodoris danielsseni, Onchidoris depressa, Palio nothus, Tritonia griegi, Tritonia lineata, Hero formosa, Janolus cristatus, Cumanotus beaumonti, Berghia norvegica and Calma glau- coides), in some cases with considerable changes to their distribution. These new results present an update to our previous extensive investigation of the nudibranch fauna of the Norwegian coast from 2005, which now totals 87 species. An increase in several new species to the Norwegian fauna and new records of rare species, some with considerable updates, in relatively few years results mainly from sampling effort and contributions by specialists on samples from poorly sampled areas. doi: 10.5324/fn.v31i0.1576. Received: 2012-12-02. Accepted: 2012-12-20. Published on paper and online: 2013-02-13. Keywords: Nudibranchia, Gastropoda, taxonomy, biogeography 1. Museum of Natural History and Archaeology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway Corresponding author: Jussi Evertsen E-mail: [email protected] IntRODUCTION the main aims. -

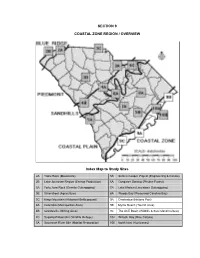

Coastal Zone Region / Overview

SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & Canals) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy Production) 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite Outcropping) 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical Battleground) 9A Charleston (Historic Port) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island Culture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat Restoration) 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW - Index Map to Coastal Zone Overview Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 9 - Power Thinking Activity - "Turtle Trot" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 9-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Coastal Zone p. 9-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 9-3 . - Carolina Grand Strand p. 9-3 . - Santee Delta p. 9-4 . - Sea Islands - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 9-5 . - Coastal Zone Attracts Settlers p. 9-5 . - Native American Coastal Cultures p. 9-5 . - Early Spanish Settlements p. 9-5 . - Establishment of Santa Elena p. 9-6 . - Charles Towne: First British Settlement p. 9-6 . - Eliza Lucas Pinckney Introduces Indigo p. 9-7 . - figure 9-1 - "Map of Colonial Agriculture" p. 9-8 . - Pirates: A Coastal Zone Legacy p. 9-9 . - Charleston Under Siege During the Civil War p. 9-9 . - The Battle of Port Royal Sound p. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Phylogenomic Resolution of Sea Spider Diversification Through Integration Of

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929612; this version posted February 2, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Phylogenomic resolution of sea spider diversification through integration of multiple data classes 1Jesús A. Ballesteros†, 1Emily V.W. Setton†, 1Carlos E. Santibáñez López†, 2Claudia P. Arango, 3Georg Brenneis, 4Saskia Brix, 5Esperanza Cano-Sánchez, 6Merai Dandouch, 6Geoffrey F. Dilly, 7Marc P. Eleaume, 1Guilherme Gainett, 8Cyril Gallut, 6Sean McAtee, 6Lauren McIntyre, 9Amy L. Moran, 6Randy Moran, 5Pablo J. López-González, 10Gerhard Scholtz, 6Clay Williamson, 11H. Arthur Woods, 12Ward C. Wheeler, 1Prashant P. Sharma* 1 Department of Integrative Biology, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI, USA 2 Queensland Museum, Biodiversity Program, Brisbane, Australia 3 Zoologisches Institut und Museum, Cytologie und Evolutionsbiologie, Universität Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany 4 Senckenberg am Meer, German Centre for Marine Biodiversity Research (DZMB), c/o Biocenter Grindel (CeNak), Martin-Luther-King-Platz 3, Hamburg, Germany 5 Biodiversidad y Ecología Acuática, Departamento de Zoología, Facultad de Biología, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain 6 Department of Biology, California State University-Channel Islands, Camarillo, CA, USA 7 Départment Milieux et Peuplements Aquatiques, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France 8 Institut de Systématique, Emvolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), Sorbonne Université, CNRS, Concarneau, France 9 Department of Biology, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, USA Page 1 of 31 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929612; this version posted February 2, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. -

Evolution of Pycnogonid Life History Traits Eric Carl Lovely University of New Hampshire, Durham

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1999 Evolution of pycnogonid life history traits Eric Carl Lovely University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Lovely, Eric Carl, "Evolution of pycnogonid life history traits" (1999). Doctoral Dissertations. 1975. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1975 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Checklist of Marine Demersal Fishes Captured by the Pair Trawl Fisheries in Southern (RJ-SC) Brazil

Biota Neotropica 19(1): e20170432, 2019 www.scielo.br/bn ISSN 1676-0611 (online edition) Inventory Checklist of marine demersal fishes captured by the pair trawl fisheries in Southern (RJ-SC) Brazil Matheus Marcos Rotundo1,2,3,4 , Evandro Severino-Rodrigues2, Walter Barrella4,5, Miguel Petrere Jun- ior3 & Milena Ramires4,5 1Universidade Santa Cecilia, Acervo Zoológico, R. Oswaldo Cruz, 266, CEP11045-907, Santos, SP, Brasil 2Instituto de Pesca, Programa de Pós-graduação em Aquicultura e Pesca, Santos, SP, Brasil 3Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Planejamento e Uso de Recursos Renováveis, Rodovia João Leme dos Santos, Km 110, CEP 18052-780, Sorocaba, SP, Brasil 4Universidade Santa Cecília, Programa de Pós-Graduação de Auditoria Ambiental, R. Oswaldo Cruz, 266, CEP11045-907, Santos, SP, Brasil 5Universidade Santa Cecília, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sustentabilidade de Ecossistemas Costeiros e Marinhos, R. Oswaldo Cruz, 266, CEP11045-907, Santos, SP, Brasil *Corresponding author: Matheus Marcos Rotundo: [email protected] ROTUNDO, M.M., SEVERINO-RODRIGUES, E., BARRELLA, W., PETRERE JUNIOR, M., RAMIRES, M. Checklist of marine demersal fishes captured by the pair trawl fisheries in Southern (RJ-SC) Brazil. Biota Neotropica. 19(1): e20170432. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1676-0611-BN-2017-0432 Abstract: Demersal fishery resources are abundant on continental shelves, on the tropical and subtropical coasts, making up a significant part of the marine environment. Marine demersal fishery resources are captured by various fishing methods, often unsustainably, which has led to the depletion of their stocks. In order to inventory the marine demersal ichthyofauna on the Southern Brazilian coast, as well as their conservation status and distribution, this study analyzed the composition and frequency of occurrence of fish captured by pair trawling in 117 fishery fleet landings based in the State of São Paulo between 2005 and 2012. -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Rice Fields for Wildlife History, Management Recommendations and Regulatory Guidelines for South Carolina’S Coastal Impoundments

Rice Fields for Wildlife History, Management Recommendations and Regulatory Guidelines for South Carolina’s Coastal Impoundments Editors Travis Folk • Ernie Wiggers • Dean Harrigal • Mark Purcell Funding for this publication provided by US Fish and Wildlife Service’s Coastal Program, Ducks Unlimited, ACE Basin Task Force, NOAA’s ACE Basin National Estuarine Research Reserve, Nemours Wildlife Foundation. The Atlantic Join Venture provided valuable funding for this publication. Citation: Folk , T. H., E.P. Wiggers, D.Harrigal, and M. Purcell (Editors). 2016. Rice fields for wildlife: history, management recom- mendations and regulatory guidelines for South Carolina’s managed tidal impoundments. Nemours Wildlife Founda- tion, Yemassee, South Carolina. Rice Fields for Wildlife History, Management Recommendations and Regulatory Guidelines for South Carolina’s Coastal Impoundments Table of Contents Chapter 1 South Carolina’s Rice Fields: how an agricultural empire created 1 a conservation legacy. Travis Hayes Folk, Ph.D. (Folk Land Management) Chapter 2 Understanding and Using the US Army Corps of Engineers 7 Managed Tidal Impoundment General Permit (MTI GP) (SAC 2017-00835) Travis Hayes Folk, Ph.D. Chapter 3 Management of South Atlantic Coastal Wetlands for Waterfowl 23 and Other Wildlife. R. K. “Kenny” Williams (Williams Land Management Company), Robert D. Perry (Palustrine Group), Michael B. Prevost (White Oak Forestry) Chapter 4 Managing Coastal Impoundments for Multiple Species of Water 39 Birds. Ernie P. Wiggers, Ph.D. (Nemours Wildlife Foundation), Christine Hand (South Carolina Department of Natural Resources), Felicia Sanders (South Carolina Department of Natural Resources) Appendices The ACE Basin Project Travis Hayes Folk, Ph.D. 47 Glossary of Rice Field Terminology 49 References of Supporting Literature 54 Sources for Technical Assistance and Cost Share Opportunities 57 Savannah River Rice Fields, 1936. -

Arthropoda: Pycnogonida)

European Journal of Taxonomy 286: 1–33 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.286 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Sabroux R. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. DNA Library of Life, research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:8B9DADD0-415E-4120-A10E-8A3411C1C1A4 Biodiversity and phylogeny of Ammotheidae (Arthropoda: Pycnogonida) Romain SABROUX 1, Laure CORBARI 2, Franz KRAPP 3, Céline BONILLO 4, Stépahnie LE PRIEUR 5 & Alexandre HASSANIN 6,* 1,2,6 UMR 7205, Institut de Systématique, Evolution et Biodiversité, Département Systématique et Evolution, Sorbonne Universités, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, 55 rue Buffon, CP 51, 75005 Paris, France. 3 Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. 4,5 UMS CNRS 2700, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, CP 26, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 Email: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 4 Email: [email protected] 5 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F48B4ABE-06BD-41B1-B856-A12BE97F9653 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:9E5EBA7B-C2F2-4F30-9FD5-1A0E49924F13 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:331AD231-A810-42F9-AF8A-DDC319AA351A 4 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:7333D242-0714-41D7-B2DB-6804F8064B13 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:5C9F4E71-9D73-459F-BABA-7495853B1981 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:0DCC3E08-B2BA-4A2C-ADA5-1A256F24DAA1 Abstract. The family Ammotheidae is the most diversified group of the class Pycnogonida, with 297 species described in 20 genera.