Mechanoreceptors in Early Developmental Stages of the Pycnogonida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenomic Resolution of Sea Spider Diversification Through Integration Of

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929612; this version posted February 2, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Phylogenomic resolution of sea spider diversification through integration of multiple data classes 1Jesús A. Ballesteros†, 1Emily V.W. Setton†, 1Carlos E. Santibáñez López†, 2Claudia P. Arango, 3Georg Brenneis, 4Saskia Brix, 5Esperanza Cano-Sánchez, 6Merai Dandouch, 6Geoffrey F. Dilly, 7Marc P. Eleaume, 1Guilherme Gainett, 8Cyril Gallut, 6Sean McAtee, 6Lauren McIntyre, 9Amy L. Moran, 6Randy Moran, 5Pablo J. López-González, 10Gerhard Scholtz, 6Clay Williamson, 11H. Arthur Woods, 12Ward C. Wheeler, 1Prashant P. Sharma* 1 Department of Integrative Biology, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI, USA 2 Queensland Museum, Biodiversity Program, Brisbane, Australia 3 Zoologisches Institut und Museum, Cytologie und Evolutionsbiologie, Universität Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany 4 Senckenberg am Meer, German Centre for Marine Biodiversity Research (DZMB), c/o Biocenter Grindel (CeNak), Martin-Luther-King-Platz 3, Hamburg, Germany 5 Biodiversidad y Ecología Acuática, Departamento de Zoología, Facultad de Biología, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain 6 Department of Biology, California State University-Channel Islands, Camarillo, CA, USA 7 Départment Milieux et Peuplements Aquatiques, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France 8 Institut de Systématique, Emvolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), Sorbonne Université, CNRS, Concarneau, France 9 Department of Biology, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, USA Page 1 of 31 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929612; this version posted February 2, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. -

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

FOREWORD Abundant fish and wildlife, unbroken coastal vistas, miles of scenic rivers, swamps and mountains open to exploration, and well-tended forests and fields…these resources enhance the quality of life that makes South Carolina a place people want to call home. We know our state’s natural resources are a primary reason that individuals and businesses choose to locate here. They are drawn to the high quality natural resources that South Carolinians love and appreciate. The quality of our state’s natural resources is no accident. It is the result of hard work and sound stewardship on the part of many citizens and agencies. The 20th century brought many changes to South Carolina; some of these changes had devastating results to the land. However, people rose to the challenge of restoring our resources. Over the past several decades, deer, wood duck and wild turkey populations have been restored, striped bass populations have recovered, the bald eagle has returned and more than half a million acres of wildlife habitat has been conserved. We in South Carolina are particularly proud of our accomplishments as we prepare to celebrate, in 2006, the 100th anniversary of game and fish law enforcement and management by the state of South Carolina. Since its inception, the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) has undergone several reorganizations and name changes; however, more has changed in this state than the department’s name. According to the US Census Bureau, the South Carolina’s population has almost doubled since 1950 and the majority of our citizens now live in urban areas. -

Arthropoda: Pycnogonida)

European Journal of Taxonomy 286: 1–33 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.286 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Sabroux R. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. DNA Library of Life, research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:8B9DADD0-415E-4120-A10E-8A3411C1C1A4 Biodiversity and phylogeny of Ammotheidae (Arthropoda: Pycnogonida) Romain SABROUX 1, Laure CORBARI 2, Franz KRAPP 3, Céline BONILLO 4, Stépahnie LE PRIEUR 5 & Alexandre HASSANIN 6,* 1,2,6 UMR 7205, Institut de Systématique, Evolution et Biodiversité, Département Systématique et Evolution, Sorbonne Universités, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, 55 rue Buffon, CP 51, 75005 Paris, France. 3 Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. 4,5 UMS CNRS 2700, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, CP 26, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 Email: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 4 Email: [email protected] 5 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F48B4ABE-06BD-41B1-B856-A12BE97F9653 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:9E5EBA7B-C2F2-4F30-9FD5-1A0E49924F13 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:331AD231-A810-42F9-AF8A-DDC319AA351A 4 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:7333D242-0714-41D7-B2DB-6804F8064B13 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:5C9F4E71-9D73-459F-BABA-7495853B1981 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:0DCC3E08-B2BA-4A2C-ADA5-1A256F24DAA1 Abstract. The family Ammotheidae is the most diversified group of the class Pycnogonida, with 297 species described in 20 genera. -

Segmentation and Tagmosis in Chelicerata

Arthropod Structure & Development 46 (2017) 395e418 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Arthropod Structure & Development journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/asd Segmentation and tagmosis in Chelicerata * Jason A. Dunlop a, , James C. Lamsdell b a Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science, Invalidenstrasse 43, D-10115 Berlin, Germany b American Museum of Natural History, Division of Paleontology, Central Park West at 79th St, New York, NY 10024, USA article info abstract Article history: Patterns of segmentation and tagmosis are reviewed for Chelicerata. Depending on the outgroup, che- Received 4 April 2016 licerate origins are either among taxa with an anterior tagma of six somites, or taxa in which the ap- Accepted 18 May 2016 pendages of somite I became increasingly raptorial. All Chelicerata have appendage I as a chelate or Available online 21 June 2016 clasp-knife chelicera. The basic trend has obviously been to consolidate food-gathering and walking limbs as a prosoma and respiratory appendages on the opisthosoma. However, the boundary of the Keywords: prosoma is debatable in that some taxa have functionally incorporated somite VII and/or its appendages Arthropoda into the prosoma. Euchelicerata can be defined on having plate-like opisthosomal appendages, further Chelicerata fi Tagmosis modi ed within Arachnida. Total somite counts for Chelicerata range from a maximum of nineteen in Prosoma groups like Scorpiones and the extinct Eurypterida down to seven in modern Pycnogonida. Mites may Opisthosoma also show reduced somite counts, but reconstructing segmentation in these animals remains chal- lenging. Several innovations relating to tagmosis or the appendages borne on particular somites are summarised here as putative apomorphies of individual higher taxa. -

Geological History and Phylogeny of Chelicerata

Arthropod Structure & Development 39 (2010) 124–142 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Arthropod Structure & Development journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/asd Review Article Geological history and phylogeny of Chelicerata Jason A. Dunlop* Museum fu¨r Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Research on Evolution and Biodiversity at the Humboldt University Berlin, Invalidenstraße 43, D-10115 Berlin, Germany article info abstract Article history: Chelicerata probably appeared during the Cambrian period. Their precise origins remain unclear, but may Received 1 December 2009 lie among the so-called great appendage arthropods. By the late Cambrian there is evidence for both Accepted 13 January 2010 Pycnogonida and Euchelicerata. Relationships between the principal euchelicerate lineages are unre- solved, but Xiphosura, Eurypterida and Chasmataspidida (the last two extinct), are all known as body Keywords: fossils from the Ordovician. The fourth group, Arachnida, was found monophyletic in most recent studies. Arachnida Arachnids are known unequivocally from the Silurian (a putative Ordovician mite remains controversial), Fossil record and the balance of evidence favours a common, terrestrial ancestor. Recent work recognises four prin- Phylogeny Evolutionary tree cipal arachnid clades: Stethostomata, Haplocnemata, Acaromorpha and Pantetrapulmonata, of which the pantetrapulmonates (spiders and their relatives) are probably the most robust grouping. Stethostomata includes Scorpiones (Silurian–Recent) and Opiliones (Devonian–Recent), while -

ZOOLOGICKÉ DNY České Budějovice 2016

ZOOLOGICKÉ DNY České Budějovice 2016 Sborník abstraktů z konference 11.-12. února 2016 Editoři: BRYJA Josef, SEDLÁČEK František & FUCHS Roman 1 Pořadatelé konference: Katedra zoologie, Přírodovědecká fakulta JU, České Budějovice Ústav biologie obratlovců AV ČR, v.v.i., Brno Česká zoologická společnost Biologické centrum AV ČR, v.v.i., České Budějovice Místo konání: Přírodovědecká fakulta JU a Biologické centrum AV ČR, v.v.i., České Budějovice Datum konání: 11.-12. února 2016 Řídící výbor konference: Bryja J. (Brno) Pekár S. (Brno) Drozd P. (Ostrava) Pižl V. (České Budějovice) Horsák M. (Brno) Řehák Z. (Brno) Kaňuch P. (Zvolen) Sedláček F. (České Budějovice) Krištín A. (Zvolen) Stanko M. (Košice) Macholán M. (Brno) Tkadlec E. (Olomouc) Munclinger P. (Praha) Zukal J. (Brno) BRYJA J., SEDLÁČEK F. & FUCHS R. (Eds.): Zoologické dny České Budějovice 2016. Sborník abstraktů z konference 11.-12. února 2016. Vydal: Ústav biologie obratlovců AV ČR, v.v.i., Květná 8, 603 65 Brno Grafická úprava: BRYJA J. VRBOVÁ KOMÁRKOVÁ J. 1. vydání, 2016 Náklad 450 výtisků. Doporučená cena 150 Kč. Vydáno jako neperiodická účelová publikace. Za jazykovou úpravu a obsah příspěvků jsou odpovědni jejich autoři. ISBN 978-80-87189-20-7 2 Zoologické dny České Budějovice 2016, Sborník abstraktů z konference 11.-12. února 2016 PROGRAM KONFERENCE Kongresová hala BC AV ČR Posluchárna B2 (budova "B") Posluchárna C2 (budova "C") Posluchárna C1 (budova "C") Čtvrtek 11.2.2016 09.00-09.15 Oficiální zahájení (Kongresová hala BC AV ČR) 09.15-10.00 Plenární přednáška (Kongresová -

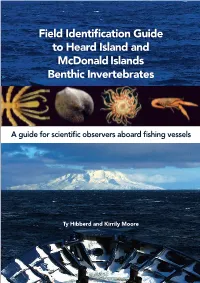

Benthic Field Guide 5.5.Indb

Field Identifi cation Guide to Heard Island and McDonald Islands Benthic Invertebrates Invertebrates Benthic Moore Islands Kirrily and McDonald and Hibberd Ty Island Heard to Guide cation Identifi Field Field Identifi cation Guide to Heard Island and McDonald Islands Benthic Invertebrates A guide for scientifi c observers aboard fi shing vessels Little is known about the deep sea benthic invertebrate diversity in the territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI). In an initiative to help further our understanding, invertebrate surveys over the past seven years have now revealed more than 500 species, many of which are endemic. This is an essential reference guide to these species. Illustrated with hundreds of representative photographs, it includes brief narratives on the biology and ecology of the major taxonomic groups and characteristic features of common species. It is primarily aimed at scientifi c observers, and is intended to be used as both a training tool prior to deployment at-sea, and for use in making accurate identifi cations of invertebrate by catch when operating in the HIMI region. Many of the featured organisms are also found throughout the Indian sector of the Southern Ocean, the guide therefore having national appeal. Ty Hibberd and Kirrily Moore Australian Antarctic Division Fisheries Research and Development Corporation covers2.indd 113 11/8/09 2:55:44 PM Author: Hibberd, Ty. Title: Field identification guide to Heard Island and McDonald Islands benthic invertebrates : a guide for scientific observers aboard fishing vessels / Ty Hibberd, Kirrily Moore. Edition: 1st ed. ISBN: 9781876934156 (pbk.) Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Benthic animals—Heard Island (Heard and McDonald Islands)--Identification. -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 106, NUMBER 18 ON THE EVOLUTIONARY SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PYCNOGONIDA (With One Plate) BY joi<:l w. hedgpeth Marine Biologist, Texas Game, Fish and Oyster Commission (PuiiLICATIUN 3866) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION MARCH 24, 1947 SA'IITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 106, NUMBER 18 ON THE EVOLUTIONARY SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PYCNOGONIDA (With One Plate) BY JOEL W. HEDGPETH Marine Biologist, Texas Game, Fish and Oyster Commission (Publication 3866) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION MARCH 24. 1947 BALTIMORE, MD., U. S. A. ON THE EVOLUTIONARY SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PYCNOGONIDA By JOEL W. HEDGPETH Marine Biologist, Texas Game, Fish and Oyster Commission (With One Plate) INTRODUCTORY NOTE The Pycnogonida, or sea spiders, are an anomalous class or sub- phylum of marine arthropods, unknown except by name to most zo- ologists. They are of no economic importance to man, and of little discernible significance in the natural order of things. Yet within the last lo years more than 50 papers dealing with these creatures have been published, and the complete bibliography now comprises several hundred titles. More than 500 species have been described, but there are relatively few parts of the world in which the pycnogonid fauna is adequately known, and the actual number of extant species may be considerably larger. Also known as Pantopoda, the Pycnogonida have often been con- sidered an "appendix" to the Arachnida in comprehensive treatises, but they have no real relationship to the arachnids, since at no stage in their development do they have a cephalothorax or prominent abdo- men. -

Fossil Calibrations for the Arthropod Tree of Life

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/044859; this version posted June 10, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. FOSSIL CALIBRATIONS FOR THE ARTHROPOD TREE OF LIFE AUTHORS Joanna M. Wolfe1*, Allison C. Daley2,3, David A. Legg3, Gregory D. Edgecombe4 1 Department of Earth, Atmospheric & Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 2 Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK 3 Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PZ, UK 4 Department of Earth Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Fossil age data and molecular sequences are increasingly combined to establish a timescale for the Tree of Life. Arthropods, as the most species-rich and morphologically disparate animal phylum, have received substantial attention, particularly with regard to questions such as the timing of habitat shifts (e.g. terrestrialisation), genome evolution (e.g. gene family duplication and functional evolution), origins of novel characters and behaviours (e.g. wings and flight, venom, silk), biogeography, rate of diversification (e.g. Cambrian explosion, insect coevolution with angiosperms, evolution of crab body plans), and the evolution of arthropod microbiomes. We present herein a series of rigorously vetted calibration fossils for arthropod evolutionary history, taking into account recently published guidelines for best practice in fossil calibration. -

PYCNOGONIDS Sea Spiders of California

PYCNOGONIDS Sea Spiders of California Sea spiders are neither spiders nor crustaceans. They are a separate class of the phylum Arthropoda (or a separate sub phylum according to some). They do, however, have considerable gross anatomical similarity to spiders. The following comments on the general anatomy and natural history of sea spiders are drawn in large part from a semi-popular synopsis by King (1974) augmented with observations by others (particularly Bouvier 1923). King's account is recommended to all interested in the ecology or taxonomy of California sea spiders. STRUCTURE most pycnogonids have four pairs of legs although species with five or six pairs are found elsewhere in the world (Fry and Hedgpeth 1969), and may be located in waters offshore California An anterior proboscis, a dorsal ocular tubercle, and a posterior abdomen are found along the midline of the body (Fig. 1). The ocular tubercle may either be absent (as m the aberrant interstitial Rhqnchothorax) or may range from a low nub to a long thin "turret" raised far above the dorsum. It may be followed by one or more anoculate tubercles along the dorsal midline. The abdomen may in some species protrude above the dorsum rather than posteriorly. Three other types of appendages occur: chelifores, palps, and ovigers. Chelifores are short, 1-4 segmented limbs above the proboscis, usually ending in chelae. Posterioventral from these a pair of palps are located in some species Chelifores and palps are not present in all species, and their structure varies with age in some families. The chelifores may be chelate in the young and achelate in the adult (eg. -

Larvae of the Pycnogonids Ammothea Gigantea Gordon, 1932 and Achelia Cuneatis Child, 1999 Described from Archived Specimens

Arthropods, 2012, 1(4):121-128 Article Larvae of the pycnogonids Ammothea gigantea Gordon, 1932 and Achelia cuneatis Child, 1999 described from archived specimens John A. Fornshell, Frank D. Ferrari National Museum of Natural History, Department of invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland, Maryland 20746, USA E-mail: [email protected] Received 30 July 2012; Accepted 2 September 2012; Published online 1 December 2012 IAEES Abstract The larvae of two species of Pycnogonida are described from archived collections. Achelia cuneatis Child, 1999 is an example of a typical protonymphon larva in having three pairs of three segmented appendages, cheliphores, palps and ovigerous appendages. Ammothea gigantea Gordon, 1932 is an example of a lecithotrophic protonymphon larva, having the three pair of appendages plus buds of the first walking legs. Ammothea gigantea is the third species known to have this larval type. The Achelia cuneatis protonymphon larvae is oval, 150 µm long and characterized by a relatively long spinneret spine arising at the distal end of the first segment of each cheliphore. Spines also arise from the distal end of the first segment of the second and third limbs. This typical protonymphon larva of Achelia cuneatis has few yolk granules. The lecithotrophic protonymphon of Ammothea gigantea lacks a spinneret spine on the cheliphore; the larva is oval in shape, but much larger than Achelia cuneatis with a length of 700 µm. Its second limb is much larger than the third limb on the first post-embryonic stage, and the third limb is further reduced to a spine-like structure on the second post-embryonic stage. -

Biodiversity and Phylogeny of Ammotheidae

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: European Journal of Taxonomy Jahr/Year: 2017 Band/Volume: 0286 Autor(en)/Author(s): Sabroux Romain, Corbari Laure, Krapp Franz, Bonillo Celine, Le Prieur Stephanie, Hassanin Alexandre Artikel/Article: Biodiversity and phylogeny of Ammotheidae (Arthropoda: Pycnogonida) 1-33 European Journal of Taxonomy 286: 1–33 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.286 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Sabroux R. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. DNA Library of Life, research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:8B9DADD0-415E-4120-A10E-8A3411C1C1A4 Biodiversity and phylogeny of Ammotheidae (Arthropoda: Pycnogonida) Romain SABROUX 1, Laure CORBARI 2, Franz KRAPP 3, Céline BONILLO 4, Stépahnie LE PRIEUR 5 & Alexandre HASSANIN 6,* 1,2,6 UMR 7205, Institut de Systématique, Evolution et Biodiversité, Département Systématique et Evolution, Sorbonne Universités, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, 55 rue Buffon, CP 51, 75005 Paris, France. 3 Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. 4,5 UMS CNRS 2700, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, CP 26, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 Email: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 4 Email: [email protected] 5 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F48B4ABE-06BD-41B1-B856-A12BE97F9653 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:9E5EBA7B-C2F2-4F30-9FD5-1A0E49924F13 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:331AD231-A810-42F9-AF8A-DDC319AA351A 4 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:7333D242-0714-41D7-B2DB-6804F8064B13 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:5C9F4E71-9D73-459F-BABA-7495853B1981 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:0DCC3E08-B2BA-4A2C-ADA5-1A256F24DAA1 Abstract.