Cities of the Future Anna Greenspan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shanghai Tower Construction & Development Co., Ltd

Autodesk Customer Success Story Shanghai Tower Construction & Development Co., Ltd. COMPANY Shanghai Tower Rising to new heights with BIM. Construction & Development Co., Ltd. Shanghai Tower owner champions BIM PROJECT TEAM for design and construction of one of the Gensler Thornton Tomasetti Cosentini Associates world’s tallest (and greenest) buildings. Architectural Design and Research Institute of Tongji University Shanghai Xiandai Engineering Consultants Co., Ltd. Shanghai Construction Group Shanghai Installation Engineering Engineering Co., Ltd. Autodesk Consulting SOFTWARE Autodesk® Revit® Autodesk® Navisworks® Manage Autodesk® Ecotect® Analysis AutoCAD® Autodesk BIM solutions enable the different design disciplines to work together in a seamless fashion on a single information platform—improving efficiency, reducing Image courtesy of Shanghai Tower Construction and Development Co., Ltd. Rendering by Gensler. errors, and improving Project summary featuring a public sky garden, together with cafes, both project and building restaurants, and retail space. The double-skinned A striking new addition to the Shanghai skyline is performance. facade creates a thermal buffer zone to minimize currently rising in the heart of the city’s financial heat gain, and the spiraling nature of the outer district. The super high-rise Shanghai Tower will — Jianping Gu facade maximizes daylighting and views while Director and General Manager soon stand as the world’s second tallest building, reducing wind loads and conserving construction Shanghai Tower Construction and adjacent to two other iconic structures, the materials. To save energy, the facility includes & Development Co., Ltd. Jin Mao Tower and the Shanghai World Financial its own wind farm and geothermal system. In Center. The 121-story transparent glass tower will addition, rainwater recovery and gray water twist and taper as it rises, conveying a unique recycling systems reduce water usage. -

CTBUH Journal

About the Council The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, based at the Illinois Institute of Technology in CTBUH Journal Chicago and with a China offi ce at Tongji International Journal on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat University in Shanghai, is an international not-for-profi t organization supported by architecture, engineering, planning, development, and construction professionals. Founded in 1969, the Council’s mission is to disseminate multi- Tall buildings: design, construction, and operation | 2014 Issue IV disciplinary information on tall buildings and sustainable urban environments, to maximize the international interaction of professionals involved Case Study: One Central Park, Sydney in creating the built environment, and to make the latest knowledge available to professionals in High-Rise Housing: The Singapore Experience a useful form. The Emergence of Asian Supertalls The CTBUH disseminates its fi ndings, and facilitates business exchange, through: the Achieving Six Stars in Sydney publication of books, monographs, proceedings, and reports; the organization of world congresses, Ethical Implications of international, regional, and specialty conferences The Skyscraper Race and workshops; the maintaining of an extensive website and tall building databases of built, under Tall Buildings in Numbers: construction, and proposed buildings; the Unfi nished Projects distribution of a monthly international tall building e-newsletter; the maintaining of an Talking Tall: Ben van Berkel international resource center; the bestowing of annual awards for design and construction excellence and individual lifetime achievement; the management of special task forces/working groups; the hosting of technical forums; and the publication of the CTBUH Journal, a professional journal containing refereed papers written by researchers, scholars, and practicing professionals. -

Read Book Skyscrapers: a History of the Worlds Most Extraordinary

SKYSCRAPERS: A HISTORY OF THE WORLDS MOST EXTRAORDINARY BUILDINGS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Judith Dupre, Adrian Smith | 176 pages | 05 Nov 2013 | Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers Inc | 9781579129422 | English | New York, United States Skyscrapers: A History of the Worlds Most Extraordinary Buildings PDF Book By crossing the boundaries of strict geometry and modern technologies in architecture, he came up with a masterpiece that has more than a twist in its tail. Item added to your basket. Sophia McCutchen rated it it was amazing Nov 27, The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Standing meters high and weighing half a million tons, Burj Khalifa towers above its city like a giant redwood in a field of daisies. The observation deck on the 43rd floor offers stunning views of Central, one of Hong Kong's busiest districts. It was the tallest of all buildings in the European Union until London's The Shard bumped it to second in The Shard did it, slicing up the skyline and the record books with its meter height overtaking the Commerzbank Headquarters in Frankfurt by nine meters, to become the highest building in the European Union. That it came about due to auto mogul Walter P. Marina Bay Sands , 10 Bayfront Ave. Heather Tribe rated it it was amazing Dec 01, Standing 1, feet tall, the building was one of the first to use new advanced structural engineering that could withstand typhoon winds as well as earthquakes ranging up to a seven on the Richter scale. Construction — mainly using concrete and stone — began around 72AD and finished in 80AD. -

1°-2° GIORNO: GENOVA / MILANO / PECHINO Volo Aereo Torino/Pechino Capital Della Durata Di Circa 11H

Cina 1°-2° GIORNO: GENOVA / MILANO / PECHINO Volo aereo Torino/Pechino Capital della durata di circa 11h. 30 min. e 1 scalo di 1h. ad Amsterdam (KLM-China Southern) con partenza alle 11.45 ed arrivo a Pechino alle 06.15 del giorno dopo (+ 6h. di fuso orario). Pechino o Beijing, letteralmente "Capitale del nord" è una delle 7 antiche Capitali della Cina (le altre furono Nanchino, Luoyang, Xi'an, Kaifeng, Hangzhou, Anyang), 3° città della Cina, 3° città al mondo (21.7 milioni di abitanti) e 8° area metropolitana del pianeta (24.9 milioni di abitanti). Mattina Trasferimento della durata di circa 40-50 min. dall’Aeroporto al Centro città distretto Dong Cheng al Novotel Beijing Peace (transfert organizzato) nella zona di Dong Cheng. Spazi pubblici Dopo un po' di relax, breve passeggiata nei dintorni dell’albergo (isolato attorno a Dongsi South Street, Dengshikou Street, Wangfujing Street e Jinyu Hutong) e nella zona dello Shijia Hutong. (EVENTUALE VISITA) Musei • Beijing Shijia Hutong Museum, nato dalla collaborazione tra la Municipalità e la Fondazione del Principe Carlo, il museo racconta la storia e lo sviluppo dell’Hutong Shijia dall’epoca Qing (1644- 1911) fino agli anni ’80. Sono esposti oggetti di artigianato, modelli, fotografie e due stanze con arredi degli anni ’50-‘60 e ’70- ’80. (10 min. a piedi dall’hotel) orari: 9:30-12:00 / 14:00-16.30 da martedì a domenica, ingresso gratuito info: https://www.chinahighlights.com/beijing/attraction/shijia-hutong-museum.htm Pomeriggio Spazi pubblici Trasferimento della durata di circa 20/25 min. verso la zona ovest del centro di Pechino per passeggiata nel parco Beihai e giro degli Hutong - vicoli o viuzze formate da linee di Siheyuan, complesso di case organizzate attorno ad un cortile)- Nanguafang, Skewed Tobacco Pouch Street, Mao’er, Nanluoguxiang e Gulou (percorso a piedi 5 min., metro linea 5 salita Dengshikou uscita C, cambio Dongsi, metro linea 6 discesa Beihai North uscita D). -

Structural Design Challenges of Shanghai Tower

Structural Design Challenges of Shanghai Tower Author: Yi Zhu Affiliation: American Society of Social Engineers Street Address: 398 Han Kou Road, Hang Sheng Building City: Shanghai State/County: Zip/Postal Code: 200001 Country: People’s Republic of China Email Address: [email protected] Fax: 1.917.661.7801 Telephone: 011.86.21.6057.0902 Website: http://www.thorntontomasetti.com Author: Dennis Poon Affiliation: Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat Street Address: 51 Madison Avenue City: New York State/County: NY Zip/Postal Code: 10010 Country: United States of America Email Address: [email protected] Fax: 1.917.661.7801 Telephone: 1.917.661.7800 Website: http://www.thorntontomasetti.com Author: Emmanuel E. Velivasakis Affiliation: American Society of Civil Engineers Street Address: 51 Madison Avenue City: New York State/County: NY Zip/Postal Code: 10010 Country: Unites States of America Email Address: [email protected] Fax: +1.917.661.7801 Telephone: +1.917.661.8072 Website: http://www.thorntontomasetti.com Author: Steve Zuo Affiliation: American Institute of Steel Construction; Structural Engineers Association of New York; American Society of Civil Engineers Street Address: 51 Madison Avenue City: New York State/County: NY Zip/Postal Code: 10010 Country: United States of America Email Address: [email protected] Fax: 1.917.661.7801 Telephone: 1.917.661.7800 Website: http://www.thorntontomasetti.com/ Author: Paul Fu Affiliation: Street Address: 51 Madison Avenue City: New York State/County: NY Zip/Postal Code: 10010 Country: United States of America Email Address: [email protected] Fax: 1.917.661.7801 Telephone: 1.917.661.7800 Website: http://www.thorntontomasetti.com/ Author Bios Yi Zhu, Senior Principal of Thornton Tomasetti, has extensive experience internationally in the structural analysis, design and review of a variety of building types, including high-rise buildings and mixed-use complexes, in both steel and concrete. -

An All-Time Record 97 Buildings of 200 Meters Or Higher Completed In

CTBUH Year in Review: Tall Trends All building data, images and drawings can be found at end of 2014, and Forecasts for 2015 Click on building names to be taken to the Skyscraper Center An All-Time Record 97 Buildings of 200 Meters or Higher Completed in 2014 Report by Daniel Safarik and Antony Wood, CTBUH Research by Marty Carver and Marshall Gerometta, CTBUH 2014 showed further shifts towards Asia, and also surprising developments in building 60 58 14,000 13,549 2014 Completions: 200m+ Buildings by Country functions and structural materials. Note: One tall building 200m+ in height was also completed during 13,000 2014 in these countries: Chile, Kuwait, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, 50 Taiwan, United Kingdom, Vietnam 60 58 2014 Completions: 200m+ Buildings by Countr5,00y 0 14,000 60 13,54958 14,000 13,549 2014 Completions: 200m+ Buildings by Country Executive Summary 40 Note: One tall building 200m+ in height was also completed during ) Note: One tall building 200m+ in height was also completed during 13,000 60 58 13,0014,000 2014 in these countries: Chile, Kuwait, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, (m 13,549 2014 in these Completions: countries: Chile, Kuwait, 200m+ Malaysia, BuildingsSingapore, South byKorea, C ountry 50 Total Number (Total = 97) 4,000 s 50 Taiwan,Taiwan, United United Kingdom, Kingdom, Vietnam Vietnam Note: One tall building 200m+ in height was also completed during ht er 13,000 Sum of He2014 igin theseht scountries: (Tot alChile, = Kuwait, 23,333 Malaysia, m) Singapore, South Korea, 5,000 mb 30 50 5,000 The Council -

China Megastructures: Learning by Experience

AC 2009-131: CHINA MEGASTRUCTURES: LEARNING BY EXPERIENCE Richard Balling, Brigham Young University Page 14.320.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2009 CHINA MEGA-STRUCTURES: LEARNING BY EXPERIENCE Abstract A study abroad program for senior and graduate civil engineering students is described. The program provides an opportunity for students to learn by experience. The program includes a two-week trip to China to study mega-structures such as skyscrapers, bridges, and complexes (stadiums, airports, etc). The program objectives and the methods for achieving those objectives are described. The relationships between the program objectives and the college educational emphases and the ABET outcomes are also presented. Student comments are included from the first offering of the program in 2008. Introduction This paper summarizes the development of a study abroad program to China where civil engineering students learn by experience. Consider some of the benefits of learning by experience. Experiential learning increases retention, creates passion, and develops perspective. Some things can only be learned by experience. Once, while the author was lecturing his teenage son for a foolish misdeed, his son interrupted him with a surprisingly profound statement, "Dad, leave me alone....sometimes you just got to be young and stupid before you can be old and wise". As parents, it's difficult to patiently let our children learn by experience. The author traveled to China for the first time in 2007. He was blindsided by the rapid pace of change in that country, and by the remarkable new mega-structures. More than half of the world's tallest skyscrapers, longest bridges, and biggest complexes (stadiums, airports, etc) are in China, and most of these have been constructed in the past decade. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 282 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/privacy. OUR READERS Dai Min Many thanks to the travellers who used the Massive thanks to Dai Lu, Li Jianjun and Cheng Yuan last edition and wrote to us with helpful hints, for all their help and support while in Shanghai, your useful advice and interesting anecdotes: Thomas assistance was invaluable. Gratitude also to Wang Chabrieres, Diana Cioffi, Matti Laitinen, Stine Schou Ying and Ju Weihong for helping out big time and a Lassen, Cristina Marsico, Rachel Roth, Tom Wagener huge thank you to my husband for everything. -

The Global Tall Building Picture: Impact of 2018

Tall Buildings in Numbers The Global Tall Building Picture: Impact of 2018 In 2018, 143 buildings of 200 meters’ height or greater were completed. This is a slight decrease from 2017’s record-breaking total of 147, and it brings the total number of 200-meter-plus buildings in the world to 1,478, marking an increase of 141 percent from 2010, and 464 percent from 2000, when only 262 existed. Asia continued to be the most dominant region in terms of skyscraper construction, and China within it, as in several years previously. For more analysis of 2018 completions, see “CTBUH Year in Review: Tall Trends of 2018,” pages 40-47. World’s Tallest Building Completed Each Year Starting with the year 2003, these are the tallest buildings that have been completed globally each year. 800 m Guangzhou CTF Finance Centre Burj Khalifa 530 m/1,739 ft 828 m/2,717 ft Dubai Guangzhou 700 m Shanghai World Financial Center Shanghai Tower Makkah Royal Clock Tower 492 m/1,614 ft 632 m/2,073 ft Two International Finance Centre 601 m/1,972 ft Ping An Finance Center Shanghai Shanghai 412 m/1,352 ft Mecca 599 m/1,965 ft Hong Kong Shenzhen 600 m One World Trade Center Trump International Hotel & Tower China Zun TAIPEI 101 541 m/1,776 ft 423 m/1,389 ft KK100 528 m/1,731 ft 508 m/1,667 ft New York City Chicago 442 m/1,449 ft Beijing Taipei Shenzhen 500 m JW Marriott Marquis Hotel Dubai Tower 2 Shimao International Plaza 355 m/1,166 ft 333 m/1,094 ft Dubai Shanghai Rose Rayhaan 400 m by Rotana Q1 Tower 333 m/1,093 ft 323 m/1,058 ft Dubai Gold Coast 300 m 200 m 100 m 2011 -

S40410-021-00136-Z.Pdf

Roche Cárcel City Territ Archit (2021) 8:7 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-021-00136-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The spatialization of time and history in the skyscrapers of the twenty-frst century in Shanghai Juan Antonio Roche Cárcel* Abstract This article aims to fnd out to what extent the skyscrapers erected in the late twentieth and early twenty-frst cen- turies, in Shanghai, follow the modern program promoted by the State and the city and how they play an essential role in the construction of the temporary discourse that this modernization entails. In this sense, it describes how the city seeks modernization and in what concrete way it designs a modern temporal discourse. The work fnds out what type of temporal narrative expresses the concentration of these skyscrapers on the two banks of the Huangpu, that of the Bund and that of the Pudong, and fnally, it analyzes the seven most representative and sig- nifcant skyscrapers built in the city in recent years, in order to reveal whether they opt for tradition or modernity, globalization or the local. The work concludes that the past, present and future of Shanghai have been minimized, that its history has been shortened, that it is a liminal site, as its most outstanding skyscrapers, built on the edge of the river and on the border between past and future. For this reason, the author defends that Shanghai, by defn- ing globalization, by being among the most active cities in the construction of skyscrapers, by building more than New York and by building increasingly technologically advanced tall towers, has the possibility to devise a peculiar Chinese modernity, or even deconstruct or give a substantial boost to the general concept of Western modernity. -

List of World's Tallest Buildings in the World

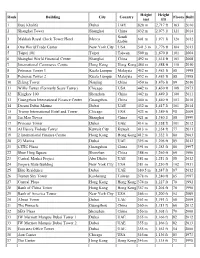

Height Height Rank Building City Country Floors Built (m) (ft) 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 2 Shanghai Tower Shanghai China 632 m 2,073 ft 121 2014 Saudi 3 Makkah Royal Clock Tower Hotel Mecca 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Arabia 4 One World Trade Center New York City USA 541.3 m 1,776 ft 104 2013 5 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m 1,670 ft 101 2004 6 Shanghai World Financial Center Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 7 International Commerce Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 8 Petronas Tower 1 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 8 Petronas Tower 2 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 10 Zifeng Tower Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 11 Willis Tower (Formerly Sears Tower) Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 12 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 100 2011 13 Guangzhou International Finance Center Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 14 Dream Dubai Marina Dubai UAE 432 m 1,417 ft 101 2014 15 Trump International Hotel and Tower Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 16 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 17 Princess Tower Dubai UAE 414 m 1,358 ft 101 2012 18 Al Hamra Firdous Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,354 ft 77 2011 19 2 International Finance Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 412 m 1,352 ft 88 2003 20 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012 21 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 22 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 23 Central Market Project Abu Dhabi UAE 381 m 1,251 ft 88 2012 24 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 -

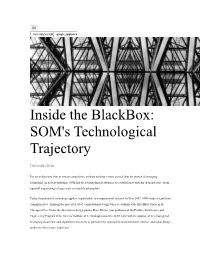

Inside the Blackbox: SOM's Technological Trajectory

GO form-RKZxvrsDm google_appliance Inside the BlackBox: SOM's Technological Trajectory Introduction For an architecture firm to remain competitive, perhaps nothing is more critical than the pursuit of emerging technology. In its best buildings, SOM has used technological advances to establish new systems of architecture, from supertall engineering to large-scale sustainable urban plans. Today the pursuit of technology applies, in particular, to computational systems. In May 2007, SOM made a significant commitment to exploring the nascent field of computational design when it established the BlackBox studio in the Chicago office. Under the direction of design partner Ross Wimer, four graduates of the Product Architecture and Engineering Program at the Stevens Institute of Technology joined the SOM team with the purpose of developing and leveraging parametric and algorithmic processes to generate new approaches to architectural, interior, and urban design within the firm’s own “black box”. BlackBox’s incubation within SOM marks a significant (re)turn to technical mediation in the service of rational form- making, recalling investigations of earlier SOM studios. Several of the firm’s most well-known architects and engineers—including Walter Netsch, Fazlur Khan, and Bruce Graham—foreshadowed similar methods of algorithmic design as early as the 1960s. Close-up of the U.S. Air Force Academy Cadet Chapel, composed of 100 tetrahedrons A History of Technological Innovation Using Field Theory, a system based on Greek geometry that relied heavily on recursive calculation, architect Walter Netsch developed manual drafts of buildings that prefigured the type of complex designs that now populate the contemporary architectural landscape. For instance, Netsch’s design for the U.S.