Postgate 1992.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2210 Bc 2200 Bc 2190 Bc 2180 Bc 2170 Bc 2160 Bc 2150 Bc 2140 Bc 2130 Bc 2120 Bc 2110 Bc 2100 Bc 2090 Bc

2210 BC 2200 BC 2190 BC 2180 BC 2170 BC 2160 BC 2150 BC 2140 BC 2130 BC 2120 BC 2110 BC 2100 BC 2090 BC Fertile Crescent Igigi (2) Ur-Nammu Shulgi 2192-2190BC Dudu (20) Shar-kali-sharri Shu-Turul (14) 3rd Kingdom of 2112-2095BC (17) 2094-2047BC (47) 2189-2169BC 2217-2193BC (24) 2168-2154BC Ur 2112-2004BC Kingdom Of Akkad 2234-2154BC ( ) (2) Nanijum, Imi, Elulu Imta (3) 2117-2115BC 2190-2189BC (1) Ibranum (1) 2180-2177BC Inimabakesh (5) Ibate (3) Kurum (1) 2127-2124BC 2113-2112BC Inkishu (6) Shulme (6) 2153-2148BC Iarlagab (15) 2121-2120BC Puzur-Sin (7) Iarlaganda ( )(7) Kingdom Of Gutium 2177-2171BC 2165-2159BC 2142-2127BC 2110-2103BC 2103-2096BC (7) 2096-2089BC 2180-2089BC Nikillagah (6) Elulumesh (5) Igeshaush (6) 2171-2165BC 2159-2153BC 2148-2142BC Iarlagash (3) Irarum (2) Hablum (2) 2124-2121BC 2115-2113BC 2112-2110BC ( ) (3) Cainan 2610-2150BC (460 years) 2120-2117BC Shelah 2480-2047BC (403 years) Eber 2450-2020BC (430 years) Peleg 2416-2177BC (209 years) Reu 2386-2147BC (207 years) Serug 2354-2124BC (200 years) Nahor 2324-2176BC (199 years) Terah 2295-2090BC (205 years) Abraham 2165-1990BC (175) Genesis (Moses) 1)Neferkare, 2)Neferkare Neby, Neferkamin Anu (2) 3)Djedkare Shemay, 4)Neferkare 2169-2167BC 1)Meryhathor, 2)Neferkare, 3)Wahkare Achthoes III, 4)Marykare, 5)............. (All Dates Unknown) Khendu, 5)Meryenhor, 6)Neferkamin, Kakare Ibi (4) 7)Nykare, 8)Neferkare Tereru, 2167-2163 9)Neferkahor Neferkare (2) 10TH Dynasty (90) 2130-2040BC Merenre Antyemsaf II (All Dates Unknown) 2163-2161BC 1)Meryibre Achthoes I, 2)............., 3)Neferkare, 2184-2183BC (1) 4)Meryibre Achthoes II, 5)Setut, 6)............., Menkare Nitocris Neferkauhor (1) Wadjkare Pepysonbe 7)Mery-........, 8)Shed-........, 9)............., 2183-2181BC (2) 2161-2160BC Inyotef II (-1) 2173-2169BC (4) 10)............., 11)............., 12)User...... -

The Assyrian Infantry

Section 8: The Neo-Assyrians The Assyrian Infantry M8-01 The Assyrians of the first millennium BCE are called the Neo-Assyrians to distinguish them from their second-millennium forbears, the Old Assyrians who ran trading colonies in Asia Minor and the Middle Assyrians who lived during the collapse of civilization at the end of the Bronze Age. There is little evidence to suggest that any significant change of population took place in Assyria during these dark centuries. To the contrary, all historical and linguistic data point to the continuity of the Assyrian royal line and population. That is, as far as we can tell, the Neo-Assyrians were the descendants of the same folk who lived in northeast Mesopotamia in Sargon’s day, only now they were newer and scarier. They will create the largest empire and most effective army yet seen in this part of the world, their military might and aggression unmatched until the rise of the Romans. Indeed, the number of similarities between Rome and Assyria — their dependence on infantry, their ferocity in a siege, their system of dating years by the name of officials, their use of brutality to instill terror — suggests there was some sort of indirect connection between these nations, but by what avenue is impossible to say. All the same, if Rome is the father of the modern world, Assyria is its grandfather, something we should acknowledge but probably not boast about. 1 That tough spirit undoubtedly kept the Assyrians united and strong through the worst of the turmoil that roiled the Near East at the end of the second millennium BCE (1077-900 BCE). -

Assyrian Historiography and Liguistics

ASSYRIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY A SOURCE STUDY THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI STUDIES SOCIAL SCIENCE SERIES VOLUME III NUMBER 1 ASSYRIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY A Source Study By ALBERT TEN EYCK OLMSTEAD Associate Professor of Ancient History Assyrian International News Agency Books Online www.aina.org CONTENTS CHAPTER I Assyrian Historians and their Histories CHAPTER II The Beginnings of True History (Tiglath Pileser I) CHAPTER III The Development of Historical Writing (Ashur nasir apal and Shalmaneser III) CHAPTER IV Shamshi Adad and the Synchronistic History CHAPTER V Sargon and the Modern Historical Criticism CHAPTER VI Annals and Display Inscriptions (Sennacherib and Esarhaddon) CHAPTER VII Ashur bani apal and Assyrian Editing CHAPTER VIII The Babylonian Chronicle and Berossus CHAPTER I ASSYRIAN HISTORIANS AND THEIR HISTORIES To the serious student of Assyrian history, it is obvious that we cannot write that history until we have adequately discussed the sources. We must learn what these are, in other words, we must begin with a bibliography of the various documents. Then we must divide them into their various classes, for different classes of inscriptions are of varying degrees of accuracy. Finally, we must study in detail for each reign the sources, discover which of the various documents or groups of documents are the most nearly contemporaneous with the events they narrate, and on these, and on these alone, base our history of the period. To the less narrowly technical reader, the development of the historical sense in one of the earlier culture peoples has an interest all its own. The historical writings of the Assyrians form one of the most important branches of their literature. -

H 02-UP-011 Assyria Io02

he Hebrew Bible records the history of ancient Israel reign. In three different inscriptions, Shalmaneser III and Judah, relating that the two kingdoms were recounts that he received tribute from Tyre, Sidon, and united under Saul (ca. 1000 B.C.) Jehu, son of Omri, in his 18th year, tand became politically separate fol- usually figured as 841 B.C. Thus, Jehu, lowing Solomon’s death (ca. 935 B.C.). the next Israelite king to whom the The division continued until the Assyrians refer, appears in the same Assyrians, whose empire was expand- order as described in the Bible. But he ing during that period, exiled Israel is identified as ruling a place with a in the late eighth century B.C. different geographic name, Bit Omri But the goal of the Bible was not to (the house of Omri). record history, and the text does not One of Shalmaneser III’s final edi- shy away from theological explana- tions of annals, the Black Obelisk, tions for events. Given this problem- contains another reference to Jehu. In atic relationship between sacred the second row of figures from the interpretation and historical accura- top, Jehu is depicted with the caption, cy, historians welcomed the discovery “Tribute of Iaua (Jehu), son of Omri. of ancient Assyrian cuneiform docu- Silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden ments that refer to people and places beaker, golden goblets, pitchers of mentioned in the Bible. Discovered gold, lead, staves for the hand of the in the 19th century, these historical king, javelins, I received from him.”As records are now being used by schol- scholar Michele Marcus points out, ars to corroborate and augment the Jehu’s placement on this monument biblical text, especially the Bible’s indicates that his importance for the COPYRIGHT THE BRITISH MUSEUM “historical books” of Kings. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

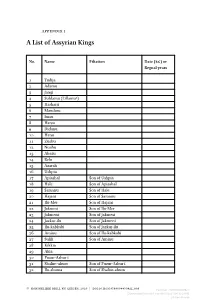

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years -

Assyrian Period (Ca. 1000•fi609 Bce)

CHAPTER 8 The Neo‐Assyrian Period (ca. 1000–609 BCE) Eckart Frahm Introduction This chapter provides a historical sketch of the Neo‐Assyrian period, the era that saw the slow rise of the Assyrian empire as well as its much faster eventual fall.1 When the curtain lifts, at the close of the “Dark Age” that lasted until the middle of the tenth century BCE, the Assyrian state still finds itself in the grip of the massive crisis in the course of which it suffered significant territorial losses. Step by step, however, a number of assertive and ruthless Assyrian kings of the late tenth and ninth centuries manage to reconquer the lost lands and reestablish Assyrian power, especially in the Khabur region. From the late ninth to the mid‐eighth century, Assyria experiences an era of internal fragmentation, with Assyrian kings and high officials, the so‐called “magnates,” competing for power. The accession of Tiglath‐pileser III in 745 BCE marks the end of this period and the beginning of Assyria’s imperial phase. The magnates lose much of their influence, and, during the empire’s heyday, Assyrian monarchs conquer and rule a territory of unprecedented size, including Babylonia, the Levant, and Egypt. The downfall comes within a few years: between 615 and 609 BCE, the allied forces of the Babylonians and Medes defeat and destroy all the major Assyrian cities, bringing Assyria’s political power, and the “Neo‐Assyrian period,” to an end. What follows is a long and shadowy coda to Assyrian history. There is no longer an Assyrian state, but in the ancient Assyrian heartland, especially in the city of Ashur, some of Assyria’s cultural and religious traditions survive for another 800 years. -

Gestures Toward Babylonia in the Imgur-Enlil Inscription of Shalmaneser III of Assyria

ORIENT Volume 49, 2014 Religion, Politics, and War: Gestures toward Babylonia in the Imgur-Enlil Inscription of Shalmaneser III of Assyria Amitai Baruchi-Unna The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan (NIPPON ORIENTO GAKKAI) Religion, Politics, and War: Gestures toward Babylonia in the Imgur- Enlil Inscription of Shalmaneser III of Assyria** Amitai Baruchi-Unna* During the first third of Shalmaneser III’s reign (859-824 BCE), the great Assyrian monarch was mostly preoccupied by the expanding western frontier of his kingdom and to a lesser degree by the northern frontier. While throughout these years he campaigned in either direction or both, in two sequential years, 851-850 BCE, he led his army southward, to Babylonia. Within this ʻquarter of the land’ he peacefully visited Babylonia proper and campaigned to its adjacent eastern neighbors: the Diyāla region in the north, and the land of the Chaldeans in the south. In this article I propose seeing Shalmaneser’s inscription preserved on the bronze edging of the doors of the gate of Imgur-Enlil (Tell Balawat) as the ideological and propagandistic part of the king’s endeavor to keep the south peaceful, so as to free himself to complete his western adventure. Composed in order to convey a special message, this unique inscription was built up of a variety of literary materials carefully organized to meet the expectations of a complex audience. First, I analyze the components of the text, emphasizing their linkage to other texts within and outside the corpus of royal inscriptions, an analysis that suggests that the text appealed to various tastes. -

The First Campaign of Sennacherib, King of Assyria, B.C

DEDICATED TO MY PARENTS. THE FIRST CAMPAIGN OF SENNACHERIB, KING OF ASSYRIA. (B.C. 703-2.) INTRODUCTION. Cylinder 113203. TnHE text has been copied fromn a hollow barrel cylinder of the usual type, now in thle British Museum. The cylinder is about 9½inches long, the bases being 3- inches in diameter, the diameter of the thickest portion of the barrel about 4½inches, and the perforations of the bases about I inch in diameter. The clay is reddish in colour, and very soft in parts, and owing to this softness the text appears to have suffered damage when the cylinder was discovered. The scribe has not drawn lines across the cylinder, and in conse- quence many of the lines bend considerably. The writing is very neat and clear, and of the same style as other historical inscriptions of the reign. The first 14 lines are written in half lines, that is with a distinct break, as though forming part of a hymn, but from that point to the end the lines are continuous. The first half of thle first 16 lines is badly broken, the fine clay of the surface having been completely removed, perhaps by a blow from a pick. The first 9 lines can be partly restored from Ki. 1902-5-10, 1, a fragment of a barrel cylinder of different shape from No. 113203, which gives beginnings of the first 9 and last 16 lines of a duplicate text. A 2 THE FIRST CAMPAIGN OF SENNACHERIB. Provenance. No information is available as to the site where the cylinder was discovered. -

Asurluların Kanunları Sümer Ve Hammurabi Kanunlarına Göre Çok Daha Sert Hükümler Içeriyordu

YUNAN ANADOLU İRAN MISIR HİNT Sümerler (M.Ö.4000-2350): –İlk defa yazıyı kullandılar (M.Ö.3200). –İlk siyasal örgütlenme Site şehir devletleri oluşturuldu. (Ur, Uruk, Kiş, Lagaş) –İlk yazılı kanunları yapmışlardır. (Lagaş kralı Urgakina) (İlk hukuk devletidir.) GENEL ÖZELLİKLERİ: Genellikle iklim ve yer şekillerinin uygun olduğu su kenarlarında kurulmuşlardır. • Daha çok tarıma dayalı üretim vardır. • Genellikle site (kent) devleti biçiminde oluşmuşlardır.(Polis, Nom, Site) •Çok tanrılı din yaygındır.(ilk tek tanrılı din İbranilerdedir) Yönetim anlayışları tanrısal (teokratik) –Bütünüyle tanrısal: Mısır (tanrı kral) –Yarı tanrısal: Mezopotamya (rahip kral) Sümerler –Bir yılı 354 gün olarak hesaplamışlar ve ay yılı takviminin temelini atmışlardır. –Ziggurat adında tapınaklar yapmışlar. Son katı gözlemevi olmuş ve astronomi gelişmiştir. –En önemli mülkiyet, su kanalları ve topraktır. –Patesi denilen Rahip Kralları vardır. – Sümer kanunları fidye, Hammurabi kanunları kısasa dayalıdır. – Sümer kanunları şehir veya küçük bir bölgeyi idare etmek, Babil ve Asur kanunları ise büyük bir ülke veya devleti idare etmek için yapılmıştır(Merkeziyetçi olmak için). KISAS: Suç için verilen cezanın da aynı oranda ağır olması sistemidir. Kanunların sert olması suç oranını azaltıp, devletin daha uzun süre yaşamasını sağlamak içindir. ZİGGURAT TAPINAKLAR • Anu veya An: Gök tanrısı, önceleri baş tanrıyken sonra yerini hava tanrısı Enlil almıştır. • Enlil: Hava tanrısı, tanrıların babası, tapınağı Ekur Nippur kentindeydi. • Enki: Bilgelik tanrısı • Nimmah (Ninhursag): -

Lots of Eponyms

167 LOTS OF EPONYMS By i. L. finkel and j. e. reade O Ashur, great lord! O Adad, great lord! The lot of Yahalu, the great masennu of Shalmaneser, King of Ashur; Governor of Kipshuni, Qumeni, Mehrani, Uqi, the cedar mountain; Minister of Trade. In his eponymate, his lot, may the crops of Assyria prosper and flourish! In front of Ashur and Adad may his lot fall! Millard (1994: frontispiece, pp. 8-9) has recently published new photographs and an annotated edition of YBC 7058, a terracotta cube with an inscription relating to the eponymate of Yahalu under Shalmaneser III. Much ink has already been spilled on account of this cube, most usefully by Hallo (1983), but certain points require emphasis or clarification. The object, p?ru, is a "lot", not a "die". Nonetheless the shape of the object inevitably suggests the idea of a true six-sided die, and perhaps implies that selections of this kind were originally made using numbered dice, with one number for each of six candidates. If so, it is possible that individual lots were introduced when more than six candidates began to be eligible for the post of limmu. The use of the word p?ru as a synonym for limmu in some texts, including this one, must indicate that eponyms were in some way regarded as having been chosen by lot. Lots can of course be drawn in a multitude of ways. Published suggestions favour the proposal that lots were placed in a narrow-necked bottle and shaken out one by one, an idea that seems to have originated with W. -

A Contribution to Ancient Near Eastern Chronology (C. 1600 – 900 BC)

A Contribution to Ancient Near Eastern Chronology (c. 1600 – 900 BC) Methodology Core Hypotheses Major Historical Repercussions 1 Methodology: Theory of Paradigms T. Kuhn (1962), The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Paradigm definition: ‘universally recognized scientific achievements that for a time provide model problems and solutions to a community of practitioners’ (e.g. Ptolemaic astronomy vs. Copernican astronomy; Creation-evolution vs. Darwinian evolution; etc.). 2 Paradigm Change Requirements of successful new paradigms: Resolve anomalies that triggered crisis Preserve most of the puzzle-solving solutions of ‘old’ paradigm. Criteria of good (better) paradigm: Breadth of scope (e.g. chronological/geographic) Accuracy/precision – essential for relating theory to data Consistency Fruitfulness: Integrate currently isolated historical texts Reveal new historical relationships Make testable predictions Simplicity – minimum ‘core’ and ‘subsidiary’ hypotheses. 3 Assyrian Anomalies Shalmaneser II to Adad-nirari II – current anomalies: 1) Ashur-rabi II to Ashur-nirari IV – almost complete lack of contemporary texts (only one exception) 2) Name of Shalmaneser II omitted from the Nassouhi King-list (possibly composed by Ashur-dan II) 3) The entire Assyrian eponym canon contains only three reigns with ‘repetitive eponyms’, i.e., ‘One after PN’ Shalmaneser II (1/12), Ashur-nirari IV (6/6), Tiglath-pileser II (from 3rd eponym) 4) Tiglath-pileser II: Khorsabad King-list (32 years); KAV 22 (33 eponyms) 5) Ashur-dan II to Adad-nirari II; revolutionary change in position of king’s eponym, from 1st to 2nd position 6) Shalmaneser II to Ashur-resha-ishi II; 2 burial stele expected in Ashur (Ashur-nirari IV and Ashur-rabi II), only 1 found. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 06:11:41PM Via Free Access 208 Appendix III

Appendix III The Selected Synchronistic Kings of Assyria and Babylonia in the Lacunae of A.117 1 Shamshi-Adad I / Ishme-Dagan I vs. Hammurabi The synchronization of Hammurabi and the ruling family of Shamshi-Adad I’s kingdom can be proven by the correspondence between them, including the letters of Yasmah-Addu, the ruler of Mari and younger son of Shamshi-Adad I, to Hammurabi as well as an official named Hulalum in Babylon1 and those of Ishme-Dagan I to Hammurabi.2 Landsberger proposed that Shamshi-Adad I might still have been alive during the first ten years of Hammurabi’s reign and that the first year of Ishme- Dagan I would have been the 11th year of Hammurabi’s reign.3 However, it was also suggested that Shamshi-Adad I would have died in the 12th / 13th4 or 17th / 18th5 year of Hammurabi’s reign and Ishme-Dagan I in the 28th or 31st year.6 If so, the reign length of Ishme-Dagan I recorded in the AKL might be unreliable and he would have ruled as the successor of Shamshi-Adad I only for about 11 years.7 1 van Koppen, MARI 8 (1997), 418–421; Durand, DÉPM, No. 916. 2 Charpin, ARM 26/2 (1988), No. 384. 3 Landsberger, JCS 8/1 (1954), 39, n. 44. 4 Whiting, OBOSA 6, 210, n. 205. 5 Veenhof, AP, 35; van de Mieroop, KHB, 9; Eder, AoF 31 (2004), 213; Gasche et al., MHEM 4, 52; Gasche et al., Akkadica 108 (1998), 1–2; Charpin and Durand, MARI 4 (1985), 293–343.