The Assyrian Infantry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kalhu/Nimrud: Cities and Eyes

Kalhu/Nimrud/CalahKalhu/Nimrud/Calah Cities and Eyes Noah Wiener Location Site Layout Patti-Hegalli Canal Chronology • Shalmaneser I 1274-1275 BCE • Assurnasirpal II 884-859 BCE • Shalmaneser III 859-824 BCE • Samsi-Adad V 824-811 BCE • Adad-nerari III (Shammuramat) 811-783 BCE • Tiglath-pileser III 745-727 BCE • Shalmaneser V 727-722 BCE • Sargon II 722-705 BCE • (Destruction of Nimrud 612 BCE) Assurnasirpal II • Moved capital to Kalhu, opening city with lavish feasts and celebration in 879 BCE. • Strongly militaristic, known for brutality. Captives built much of Kalhu. • Military campaigns through Syria made him the first Assyrian ruler in centuries to extend boundaries to the Mediterranean through the Levant Shalmaneser III •• CCoonnssttrruucctteedd NNiimmrruudd’’ss ZZiigggguurraatt aanndd FFoorrtt SShhaallmmaanneesseerr •• MMiilliittaarriissttiicc,, ‘‘ddeeffeeaatteedd’’ DDaammaassccuuss’’ aalllliiaannccee,, JJeehhuu ooff IIssrraaeell,, TTyyrree,, aanndd mmaannyy nneeiigghhbboorriinngg ssttaatteess •• RReeiiggnn eennddeedd iinn rreevvoolluuttiioonn • Samsi-Adad V– ended revolution, invaded Babylon • Adad-nerari III– Young King, siege in Damascus, during early years mother acted as regent. • (Period of decline) • Tiglath-Pileser III– Extremely successful conqueror, greatly extended Assyrian power. Built Central Palace, reformed Assyrian army and removed power of many officials. • Shalmaneser V– Heavy taxation leading to rebellion. • Sargon II– Successful ruler, moved capital from Kalhu. Archaeology • Austen Henry Layard 1817-1895 • Sir Max Edgar Lucien Mallowan 1904-1978 The Northwest Palace The Northwest Palace The Northwest Palace The Northwest Palace South West and Central Palaces Ziggurat Temples Fort Shalmaneser Fort Shalmaneser Residential Kalhu Two Types of Tomb Finds at Kalhu Finds at Kalhu Finds at Kalhu. -

"The Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah." Israel and Empire: a Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism

"The Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah." Israel and Empire: A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism. Perdue, Leo G., and Warren Carter.Baker, Coleman A., eds. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015. 37–68. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9780567669797.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 16:38 UTC. Copyright © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 The Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah I. Historical Introduction1 When the installation of a new monarch in the temple of Ashur occurs during the Akitu festival, the Sangu priest of the high god proclaims when the human ruler enters the temple: Ashur is King! Ashur is King! The ruler now is invested with the responsibilities of the sovereignty, power, and oversight of the Assyrian Empire. The Assyrian Empire has been described as a heterogeneous multi-national power directed by a superhuman, autocratic king, who was conceived of as the representative of God on earth.2 As early as Naram-Sin of Assyria (ca. 18721845 BCE), two important royal titulars continued and were part of the larger titulary of Assyrian rulers: King of the Four Quarters and King of All Things.3 Assyria began its military advances west to the Euphrates in the ninth century BCE. -

Nimrud) High School Activity Booklet

Palace Reliefs from Kalhu (Nimrud) High School Activity Booklet Created by Eliza Graumlich ’17 Student Education Assistant Bowdoin College Museum of Art Winged Spirit or Apkallu Anointing Ashurnasirpal II from Kalhu (Nimrud), Iraq, 875–860 BCE. Bowdoin College Museum of Art WHAT A RELIEF On November 8, 1845, a young English diplomat named Austen Henry Layard boarded a small raft in Mosul, Iraq and set off down the Tigris River, carrying with him “a variety of guns, spears, and other formidable weapons” as Layard described in his account Discoveries at Nineveh (1854). He told his companions that he was off to hunt wild boars in a nearby village but, actually, he was hoping to hunt down the remains of an ancient city. Layard previously noticed large mounds of earth near the village of Nimrud, Iraq and hoped that excavation would reveal ruins. He arrived at his destination that evening under the cover of darkness. 2 The next morning, Layard began digging with the help of seven hired locals and various tools that he had gathered in secret. He feared that Turkish officials would not grant him permission for the excavation. Within a few hours, dirt and sand gave way to stone; Layard had discovered the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Kalhu. Layard continued his excavation over the next six years, ultimately discovering “three more palaces, an arsenal, two temples, and the walls of both citadel and city” as Barbara Nevling Porter described in Trees, Kings, and Politics: Studies in Assyrian Iconography (2003) At the end of the excavation, Dr. -

H 02-UP-011 Assyria Io02

he Hebrew Bible records the history of ancient Israel reign. In three different inscriptions, Shalmaneser III and Judah, relating that the two kingdoms were recounts that he received tribute from Tyre, Sidon, and united under Saul (ca. 1000 B.C.) Jehu, son of Omri, in his 18th year, tand became politically separate fol- usually figured as 841 B.C. Thus, Jehu, lowing Solomon’s death (ca. 935 B.C.). the next Israelite king to whom the The division continued until the Assyrians refer, appears in the same Assyrians, whose empire was expand- order as described in the Bible. But he ing during that period, exiled Israel is identified as ruling a place with a in the late eighth century B.C. different geographic name, Bit Omri But the goal of the Bible was not to (the house of Omri). record history, and the text does not One of Shalmaneser III’s final edi- shy away from theological explana- tions of annals, the Black Obelisk, tions for events. Given this problem- contains another reference to Jehu. In atic relationship between sacred the second row of figures from the interpretation and historical accura- top, Jehu is depicted with the caption, cy, historians welcomed the discovery “Tribute of Iaua (Jehu), son of Omri. of ancient Assyrian cuneiform docu- Silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden ments that refer to people and places beaker, golden goblets, pitchers of mentioned in the Bible. Discovered gold, lead, staves for the hand of the in the 19th century, these historical king, javelins, I received from him.”As records are now being used by schol- scholar Michele Marcus points out, ars to corroborate and augment the Jehu’s placement on this monument biblical text, especially the Bible’s indicates that his importance for the COPYRIGHT THE BRITISH MUSEUM “historical books” of Kings. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transit Corridors And

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transit Corridors and Assyrian Strategy: Case Studies from the 8th-7th Century BCE Southern Levant A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philisophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures by Heidi Michelle Fessler 2016 © Copyright by Heidi Michelle Fessler 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transit Corridors and Assyrian Strategy: Case Studies from the 8th-7th Century BCE Southern Levant by Heidi Michelle Fessler Doctor of Philisophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Aaron Alexander Burke, Chair Several modern studies and the Assyrians themselves have claimed not only the extreme military measures but also substantial geo-political impact of Assyrian conquest in the southern Levant; however, examples of Assyrian violence and control are actually underrepresented in the archaeological record. The few scholars that have pointed out this dearth of corroborative data have attributed it to an apathetic attitude adopted by Assyria toward the region during both conquest and political control. I argue in this dissertation that the archaeological record reflects Assyrian military strategy rather than indifference. Data from three case studies, Megiddo, Ashdod, and the Western Negev, suggest that the small number of sites with evidence of destruction and even fewer sites with evidence of Assyrian imperial control are a product of a strategy that allowed Assyria to annex the region with less investment than their annals claim. ii Furthermore, Assyria’s network of imperial outposts monitored international highways in a manner that allowed a small local and foreign population to participate in trade and defense opportunities that ultimately benefited the Assyrian core. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

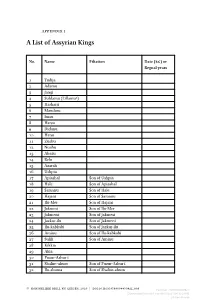

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years -

Assyrian Period (Ca. 1000•fi609 Bce)

CHAPTER 8 The Neo‐Assyrian Period (ca. 1000–609 BCE) Eckart Frahm Introduction This chapter provides a historical sketch of the Neo‐Assyrian period, the era that saw the slow rise of the Assyrian empire as well as its much faster eventual fall.1 When the curtain lifts, at the close of the “Dark Age” that lasted until the middle of the tenth century BCE, the Assyrian state still finds itself in the grip of the massive crisis in the course of which it suffered significant territorial losses. Step by step, however, a number of assertive and ruthless Assyrian kings of the late tenth and ninth centuries manage to reconquer the lost lands and reestablish Assyrian power, especially in the Khabur region. From the late ninth to the mid‐eighth century, Assyria experiences an era of internal fragmentation, with Assyrian kings and high officials, the so‐called “magnates,” competing for power. The accession of Tiglath‐pileser III in 745 BCE marks the end of this period and the beginning of Assyria’s imperial phase. The magnates lose much of their influence, and, during the empire’s heyday, Assyrian monarchs conquer and rule a territory of unprecedented size, including Babylonia, the Levant, and Egypt. The downfall comes within a few years: between 615 and 609 BCE, the allied forces of the Babylonians and Medes defeat and destroy all the major Assyrian cities, bringing Assyria’s political power, and the “Neo‐Assyrian period,” to an end. What follows is a long and shadowy coda to Assyrian history. There is no longer an Assyrian state, but in the ancient Assyrian heartland, especially in the city of Ashur, some of Assyria’s cultural and religious traditions survive for another 800 years. -

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III DESCRIPTION Akkadian Language: (Neo-Assyrian) Medium: black limestone 4 panels Size: 2.02 meters high Text length: 190 lines + 5 captions Approximate Date of Obelisk: 827 BCE Approximate Date of Jehu's Tribute: 841 BCE Dates of Shalmaneser III's reign: 858–824 BCE Date of Discovery: 1846 ancient Kalhu/Calah Place of Discovery: (modern Nimrud, Iraq) Excavator: Austen Henry Layard (1817-1894) Current Location: British Museum BM WAA 118885 Inventory Number: (BM = British Museum; WAA = Western Asiastic Antiquities) TRANSLATION (Adapted from Luckenbill 1926:200-211) (1-21) Assur, the great lord, king of all the great gods; Anu, king of the Igigi and Anunnaki, the lord of lands; Enlil, the exalted, father of the gods, the creator; Ea, king of the Deep, who determines destiny; Sin, king of the tiara, exalted in splendor; Adad, mighty, pre-eminent, lord of abundance; Shamash, judge of heaven and earth, director of all; Marduk, master of the gods, lord of law; Urta, valiant one of the Igigi and the Anunnaki, the almighty god; Nergal, the ready, king of battle; Nusku, bearer of the shining scepter, the god who renders decisions; Ninlil, spouse of Bêl, mother of the great gods; Ishtar, lady of conflict and battle, whose delight is warfare, great gods, who love my kingship, who have made great my rule, power, and sway, who have established for me an honored, an exalted name, far above that of all other lords! Shalmaneser, king of all peoples, lord, priest of Assur, mighty king, king of all the four regions, Sun of all peoples, despot of all lands; son of Assur-nâsir-pal, the high priest, whose priesthood was acceptable to the gods and who brought in submission at his feet the totality of the countries; glorious offspring of Tukulti-Urta, who slew all of his foes and overwhelmed them like a deluge. -

Gestures Toward Babylonia in the Imgur-Enlil Inscription of Shalmaneser III of Assyria

ORIENT Volume 49, 2014 Religion, Politics, and War: Gestures toward Babylonia in the Imgur-Enlil Inscription of Shalmaneser III of Assyria Amitai Baruchi-Unna The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan (NIPPON ORIENTO GAKKAI) Religion, Politics, and War: Gestures toward Babylonia in the Imgur- Enlil Inscription of Shalmaneser III of Assyria** Amitai Baruchi-Unna* During the first third of Shalmaneser III’s reign (859-824 BCE), the great Assyrian monarch was mostly preoccupied by the expanding western frontier of his kingdom and to a lesser degree by the northern frontier. While throughout these years he campaigned in either direction or both, in two sequential years, 851-850 BCE, he led his army southward, to Babylonia. Within this ʻquarter of the land’ he peacefully visited Babylonia proper and campaigned to its adjacent eastern neighbors: the Diyāla region in the north, and the land of the Chaldeans in the south. In this article I propose seeing Shalmaneser’s inscription preserved on the bronze edging of the doors of the gate of Imgur-Enlil (Tell Balawat) as the ideological and propagandistic part of the king’s endeavor to keep the south peaceful, so as to free himself to complete his western adventure. Composed in order to convey a special message, this unique inscription was built up of a variety of literary materials carefully organized to meet the expectations of a complex audience. First, I analyze the components of the text, emphasizing their linkage to other texts within and outside the corpus of royal inscriptions, an analysis that suggests that the text appealed to various tastes. -

KARUS on the FRONTIERS of the NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE I Shigeo

KARUS ON THE FRONTIERS OF THE NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE I Shigeo YAMADA * The paper discusses the evidence for the harbors, trading posts, and/or administrative centers called karu in Neo-Assyrian documentary sources, especially those constructed on the frontiers of the Assyrian empire during the ninth to seventh centuries Be. New Assyrian cities on the frontiers were often given names that stress the glory and strength of Assyrian kings and gods. Kar-X, i.e., "Quay of X" (X = a royal/divine name), is one of the main types. Names of this sort, given to cities of administrative significance, were probably chosen to show that the Assyrians were ready to enhance the local economy. An exhaustive examination of the evidence relating to cities named Kar-X and those called karu or bit-kar; on the western frontiers illustrates the advance of Assyrian colonization and trade control, which eventually spread over the entire region of the eastern Mediterranean. The Assyrian kiirus on the frontiers served to secure local trading activities according to agreements between the Assyrian king and local rulers and traders, while representing first and foremost the interest of the former party. The official in charge of the kiiru(s), the rab-kari, appears to have worked as a royal deputy, directly responsible for the revenue of the royal house from two main sources: (1) taxes imposed on merchandise and merchants passing through the trade center(s) under his control, and (2) tribute exacted from countries of vassal status. He thus played a significant role in Assyrian exploitation of economic resources from areas beyond the jurisdiction of the Assyrian provincial government. -

Textual and Visual Discourse in Ashurbanipal's North Palace

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2016 Representations of Royal Power: Textual and Visual Discourse in Ashurbanipal’s North Palace Cojocaru, Gabriela Augustina Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-135476 Dissertation Originally published at: Cojocaru, Gabriela Augustina. Representations of Royal Power: Textual and Visual Discourse in Ashur- banipal’s North Palace. 2016, University of Zurich / University of Bucharest, Faculty of Theology. University of Bucharest, Faculty of History History Doctoral School PhD Thesis in Ancient History and Archaeology Gabriela Augustina Cojocaru Representations of Royal Power: Textual and Visual Discourse in Ashurbanipal’s North Palace Advisor: Prof. Dr. Gheorghe Vlad Nistor Referents: Prof. Dr. Christoph Uehlinger (University of Zurich) Prof. Dr. Miron Ciho (University of Bucharest) Prof. Dr. Lucretiu Birliba (Al. I. Cuza University of Iasi) President of the committee: Prof. Dr. Antal Lukacs (University of Bucharest) Bucharest 2015 Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................................. ii List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................ iii List of Plates ......................................................................................................................................... -

Lots of Eponyms

167 LOTS OF EPONYMS By i. L. finkel and j. e. reade O Ashur, great lord! O Adad, great lord! The lot of Yahalu, the great masennu of Shalmaneser, King of Ashur; Governor of Kipshuni, Qumeni, Mehrani, Uqi, the cedar mountain; Minister of Trade. In his eponymate, his lot, may the crops of Assyria prosper and flourish! In front of Ashur and Adad may his lot fall! Millard (1994: frontispiece, pp. 8-9) has recently published new photographs and an annotated edition of YBC 7058, a terracotta cube with an inscription relating to the eponymate of Yahalu under Shalmaneser III. Much ink has already been spilled on account of this cube, most usefully by Hallo (1983), but certain points require emphasis or clarification. The object, p?ru, is a "lot", not a "die". Nonetheless the shape of the object inevitably suggests the idea of a true six-sided die, and perhaps implies that selections of this kind were originally made using numbered dice, with one number for each of six candidates. If so, it is possible that individual lots were introduced when more than six candidates began to be eligible for the post of limmu. The use of the word p?ru as a synonym for limmu in some texts, including this one, must indicate that eponyms were in some way regarded as having been chosen by lot. Lots can of course be drawn in a multitude of ways. Published suggestions favour the proposal that lots were placed in a narrow-necked bottle and shaken out one by one, an idea that seems to have originated with W.