Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 06:11:41PM Via Free Access 208 Appendix III

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thiele's Biblical Chronology As a Corrective for Extrabiblical Dates

Andm University Seminary Studies, Autumn 1996, Vol. 34, No. 2,295-317. Copyright 1996 by Andrews University Press.. THIELE'S BIBLICAL CHRONOLOGY AS A CORRECTIVE FOR EXTRABIBLICAL DATES KENNETH A. STRAND Andrews University The outstanding work of Edwin R. Thiele in producing a coherent and internally consistent chronology for the period of the Hebrew Divided Monarchy is well known. By ascertaining and applying the principles and procedures used by the Hebrew scribes in recording the lengths of reign and synchronisms given in the OT books of Kings and Chronicles for the kings of Israel and Judah, he was able to demonstrate the accuracy of these biblical data. What has generally not been given due notice is the effect that Thiele's clarification of the Hebrew chronology of this period of history has had in furnishing a corrective for various dates in ancient Assyrian and Babylonian history. It is the purpose of this essay to look at several such dates.' 1. i%e Basic Question In a recent article in AUSS, Leslie McFall, who along with many other scholars has shown favor for Thiele's chronology, notes five vital variable factors which Thiele recognized, and then he sets forth the following opinion: In view of the complex interaction of several of the independent factors, it is clear that such factors could never have been discovered (or uncovered) if it had not been for extrabiblical evidence which established certain key absolute dates for events in Israel and Judah, such as 853, 841, 723, 701, 605, 597, and 586 B.C. It was as a result of trial and error in fitting the biblical data around these absolute dates that previous chronologists (and more recently Thiele) brought to light the factors outlined above.= '~lthou~hmuch of the information provided in this article can be found in Thiele's own published works, the presentation given here gathers it, together with certain other data, into a context and with a perspective not hitherto considered, so far as I have been able to determine. -

The Limits of Middle Babylonian Archives1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenstarTs The Limits of Middle Babylonian Archives1 susanne paulus Middle Babylonian Archives Archives and archival records are one of the most important sources for the un- derstanding of the Babylonian culture.2 The definition of “archive” used for this article is the one proposed by Pedersén: «The term “archive” here, as in some other studies, refers to a collection of texts, each text documenting a message or a statement, for example, letters, legal, economic, and administrative documents. In an archive there is usually just one copy of each text, although occasionally a few copies may exist.»3 The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the archives of the Middle Babylonian Period (ca. 1500-1000 BC),4 which are often 1 All kudurrus are quoted according to Paulus 2012a. For a quick reference on the texts see the list of kudurrus in table 1. 2 For an introduction into Babylonian archives see Veenhof 1986b; for an overview of differ- ent archives of different periods see Veenhof 1986a and Brosius 2003a. 3 Pedersén 1998; problems connected to this definition are shown by Brosius 2003b, 4-13. 4 This includes the time of the Kassite dynasty (ca. 1499-1150) and the following Isin-II-pe- riod (ca. 1157-1026). All following dates are BC, the chronology follows – willingly ignoring all linked problems – Gasche et. al. 1998. the limits of middle babylonian archives 87 left out in general studies,5 highlighting changes in respect to the preceding Old Babylonian period and problems linked with the material. -

Ancient Near Eastern Studies

Ancient Near Eastern Studies Studies in Ancient Persia Receptions of the Ancient Near East and the Achaemenid Period in Popular Culture and Beyond edited by John Curtis edited by Lorenzo Verderame An important collection of eight essays on and Agnès Garcia-Ventura Ancient Persia (Iran) in the periods of the This book is an enthusiastic celebration Achaemenid Empire (539–330 BC), when of the ways in which popular culture has the Persians established control over the consumed aspects of the ancient Near East whole of the Ancient Near East, and later the to construct new realities. It reflects on how Sasanian Empire: stone relief carvings from objects, ideas, and interpretations of the Persepolis; the Achaemenid period in Baby- ancient Near East have been remembered, lon; neglected aspects of biblical archaeol- constructed, re-imagined, mythologized, or ogy and the books of Daniel and Isaiah; and the Sasanian period in Iran (AD indeed forgotten within our shared cultural memories. 250–650) when Zoroastrianism became the state religion. 332p, illus (Lockwood Press, March 2020) paperback, 9781948488242, $32.95. 232p (James Clarke & Co., January 2020) paperback, 9780227177068, $38.00. Special Offer $27.00; PDF e-book, 9781948488259, $27.00 Special Offer $31.00; hardcover, 9780227177051, $98.00. Special Offer $79.00 PDF e-book, 9780227907061, $31.00; EPUB e-book, 9780227907078, $30.99 Women at the Dawn of History The Synagogue in Ancient Palestine edited by Agnete W. Lassen Current Issues and Emerging Trends and Klaus Wagensonner edited by Rick Bonnie, Raimo Hakola and Ulla Tervahauta In the patriarchal world of ancient This book brings together leading experts in the field of ancient-synagogue Mesopotamia, women were often studies to discuss the current issues and emerging trends in the study of represented in their relation to men. -

Sea-L 3 Jeverling Materials Vol1.Pdf

SPECIMINA ELECTRONICA ANTIQUITATIS – LIBRI 3. 2013 ₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪ ISBN 978-963-642-508-1 Materials for the Study of First Millennium B.C. Babylonian Texts Volume 1. Chronological List of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia János Everling Pécs 2000 Matrials for the Study of the First Millennium B.C. Babylonian Texts vol. 1. Chronological List 1. Introduction Since the publication of the Chronological List of the Ur III texts 1 the attention of several scholars were drawn to the lack of information in the same field concerning the First Millennium B.C. The first attempt to complete our knowledge concerning this period were realized by M. Dandamayev2. Next year R. Zadok published a comprehensive study on the geographical repartition of the material3. Several studies were elaborated for the reconstruction of the first millennium B.C. Babylonian chronology4. The first volume of the “Materials for the Study of the First Millennium B.C. Babylonian Texts” is intended to present the material in chronological order. It was completed in September 2000. The “Materials for the Study of the First Millennium B.C. Babylonian Texts” is a series of volumes whose logical structure can be described as follows: 1. Chronological List of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia, 2. Geographical List of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia, 3. Personal Names of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia, 4. Thematic Selections from the Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia, 5. Publication of Text Editions of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. -

1. the Biblical Data Regarding Darius the Mede

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Autumn 1982, Vol. 20, No. 3, 229-217. Copyright 0 1982 by Andrews University Press. DARIUS THE MEDE: AN UPDATE WILLIAM H. SHEA Andrews University The two main historical problems which confront us in the sixth chapter of Daniel have to do with the two main historical figures in it, Darius the Mede, who was made king of Babylon, and Daniel, whom he appointed as principal governor there. The problem with Darius is that no ruler of Babylon is known from our historical sources by this name prior to the time of Darius I of Persia (522-486 B.c.). The problem with Daniel is that no governor of Babylon is known by that name, or by his Babylonian name, early in the Persian period. Daniel's position mentioned here, which has received little attention, will be discussed in a sub- sequent study. In the present article I shall treat the question of the identification of Darius the Mede, a matter which has received considerable attention, with a number of proposals having been advanced as to his identity. I shall endeavor to bring some clarity to the picture through a review of the cuneiform evidence and a comparison of that evidence with the biblical data. As a back- ground, it will be useful also to have a brief overview of the various theories that have already been advanced. 1. The Biblical Data Regarding Darius the Mede Before we consider the theories regarding the identification of Darius the Mede, however, note should be taken of the information about him that is available from the book of Daniel. -

The Assyrian Infantry

Section 8: The Neo-Assyrians The Assyrian Infantry M8-01 The Assyrians of the first millennium BCE are called the Neo-Assyrians to distinguish them from their second-millennium forbears, the Old Assyrians who ran trading colonies in Asia Minor and the Middle Assyrians who lived during the collapse of civilization at the end of the Bronze Age. There is little evidence to suggest that any significant change of population took place in Assyria during these dark centuries. To the contrary, all historical and linguistic data point to the continuity of the Assyrian royal line and population. That is, as far as we can tell, the Neo-Assyrians were the descendants of the same folk who lived in northeast Mesopotamia in Sargon’s day, only now they were newer and scarier. They will create the largest empire and most effective army yet seen in this part of the world, their military might and aggression unmatched until the rise of the Romans. Indeed, the number of similarities between Rome and Assyria — their dependence on infantry, their ferocity in a siege, their system of dating years by the name of officials, their use of brutality to instill terror — suggests there was some sort of indirect connection between these nations, but by what avenue is impossible to say. All the same, if Rome is the father of the modern world, Assyria is its grandfather, something we should acknowledge but probably not boast about. 1 That tough spirit undoubtedly kept the Assyrians united and strong through the worst of the turmoil that roiled the Near East at the end of the second millennium BCE (1077-900 BCE). -

The Selected Synchronistic Kings of Assyria and Babylonia in the Lacunae of A.117

Appendix III The Selected Synchronistic Kings of Assyria and Babylonia in the Lacunae of A.117 1 Shamshi-Adad I / Ishme-Dagan I vs. Hammurabi The synchronization of Hammurabi and the ruling family of Shamshi-Adad I’s kingdom can be proven by the correspondence between them, including the letters of Yasmah-Addu, the ruler of Mari and younger son of Shamshi-Adad I, to Hammurabi as well as an official named Hulalum in Babylon1 and those of Ishme-Dagan I to Hammurabi.2 Landsberger proposed that Shamshi-Adad I might still have been alive during the first ten years of Hammurabi’s reign and that the first year of Ishme- Dagan I would have been the 11th year of Hammurabi’s reign.3 However, it was also suggested that Shamshi-Adad I would have died in the 12th / 13th4 or 17th / 18th5 year of Hammurabi’s reign and Ishme-Dagan I in the 28th or 31st year.6 If so, the reign length of Ishme-Dagan I recorded in the AKL might be unreliable and he would have ruled as the successor of Shamshi-Adad I only for about 11 years.7 1 van Koppen, MARI 8 (1997), 418–421; Durand, DÉPM, No. 916. 2 Charpin, ARM 26/2 (1988), No. 384. 3 Landsberger, JCS 8/1 (1954), 39, n. 44. 4 Whiting, OBOSA 6, 210, n. 205. 5 Veenhof, AP, 35; van de Mieroop, KHB, 9; Eder, AoF 31 (2004), 213; Gasche et al., MHEM 4, 52; Gasche et al., Akkadica 108 (1998), 1–2; Charpin and Durand, MARI 4 (1985), 293–343. -

H 02-UP-011 Assyria Io02

he Hebrew Bible records the history of ancient Israel reign. In three different inscriptions, Shalmaneser III and Judah, relating that the two kingdoms were recounts that he received tribute from Tyre, Sidon, and united under Saul (ca. 1000 B.C.) Jehu, son of Omri, in his 18th year, tand became politically separate fol- usually figured as 841 B.C. Thus, Jehu, lowing Solomon’s death (ca. 935 B.C.). the next Israelite king to whom the The division continued until the Assyrians refer, appears in the same Assyrians, whose empire was expand- order as described in the Bible. But he ing during that period, exiled Israel is identified as ruling a place with a in the late eighth century B.C. different geographic name, Bit Omri But the goal of the Bible was not to (the house of Omri). record history, and the text does not One of Shalmaneser III’s final edi- shy away from theological explana- tions of annals, the Black Obelisk, tions for events. Given this problem- contains another reference to Jehu. In atic relationship between sacred the second row of figures from the interpretation and historical accura- top, Jehu is depicted with the caption, cy, historians welcomed the discovery “Tribute of Iaua (Jehu), son of Omri. of ancient Assyrian cuneiform docu- Silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden ments that refer to people and places beaker, golden goblets, pitchers of mentioned in the Bible. Discovered gold, lead, staves for the hand of the in the 19th century, these historical king, javelins, I received from him.”As records are now being used by schol- scholar Michele Marcus points out, ars to corroborate and augment the Jehu’s placement on this monument biblical text, especially the Bible’s indicates that his importance for the COPYRIGHT THE BRITISH MUSEUM “historical books” of Kings. -

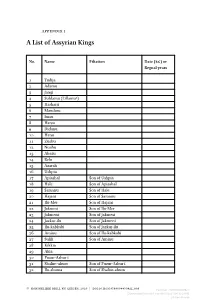

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years -

Assyrian Period (Ca. 1000•fi609 Bce)

CHAPTER 8 The Neo‐Assyrian Period (ca. 1000–609 BCE) Eckart Frahm Introduction This chapter provides a historical sketch of the Neo‐Assyrian period, the era that saw the slow rise of the Assyrian empire as well as its much faster eventual fall.1 When the curtain lifts, at the close of the “Dark Age” that lasted until the middle of the tenth century BCE, the Assyrian state still finds itself in the grip of the massive crisis in the course of which it suffered significant territorial losses. Step by step, however, a number of assertive and ruthless Assyrian kings of the late tenth and ninth centuries manage to reconquer the lost lands and reestablish Assyrian power, especially in the Khabur region. From the late ninth to the mid‐eighth century, Assyria experiences an era of internal fragmentation, with Assyrian kings and high officials, the so‐called “magnates,” competing for power. The accession of Tiglath‐pileser III in 745 BCE marks the end of this period and the beginning of Assyria’s imperial phase. The magnates lose much of their influence, and, during the empire’s heyday, Assyrian monarchs conquer and rule a territory of unprecedented size, including Babylonia, the Levant, and Egypt. The downfall comes within a few years: between 615 and 609 BCE, the allied forces of the Babylonians and Medes defeat and destroy all the major Assyrian cities, bringing Assyria’s political power, and the “Neo‐Assyrian period,” to an end. What follows is a long and shadowy coda to Assyrian history. There is no longer an Assyrian state, but in the ancient Assyrian heartland, especially in the city of Ashur, some of Assyria’s cultural and religious traditions survive for another 800 years. -

Karduniaš. Babylonia Under the Kassites

Karduniaš. Babylonia Under the Kassites The Proceedings of the Symposium Held in Munich 30 June to 2 July 2011 Tagungsbericht des Münchner Symposiums 30. Juni bis 2. Juli 2011 edited by Alexa Bartelmus and Katja Sternitzke Volume 1 Philological and Historical Studies Bereitgestellt von | Universitaetsbibliothek der LMU München Angemeldet | [email protected] Heruntergeladen am | 16.08.17 09:30 ISBN 978-1-5015-1163-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-5015-0356-6 e-ISBN (ePub) 978-1-5015-0348-1 ISSN 0502-7012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Typesetting: fidus Publikations-Service GmbH, Nördlingen Printing and binding: Druckerei Hubert & Co. GmbH und Co. KG ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Bereitgestellt von | Universitaetsbibliothek der LMU München Angemeldet | [email protected] Heruntergeladen am | 16.08.17 09:30 Jared L. Miller 3 Political Interactions between Kassite Babylonia and Assyria, Egypt and Ḫatti during the Amarna Age Introduction This paper aims first to provide a concise overview of the political interactions between Kassite Babylonia and the other Great Powers of the Amarna Age, i.e. Egypt, Ḫatti, Mittani and Assyria, a subject which could naturally fill a sizable monograph, or rather, a series of monographs. In an attempt to justify yet another general introduction to the era,1 this paper will also discuss two items to which some minor novel contribution can be made. -

ISSN 0989-5671 N°3 (Septembre) NOTES BRÈVES

ISSN 0989-5671 2016 N°3 (septembre) NOTES BRÈVES 55) Ergänzungen zu CUSAS 17, Nr. 104 — Auf dem „ancient kudurru“ CUSAS 17, Nr. 104 hat der Autor in NABU 2014 Nr. 38 den Namen PI.PI.EN als en-be6-be6 gelesen. Einer plausiblen Vermutung von Piotr Steinkeller (CUSAS 17, 217-18) zufolge handelt es sich bei dem Namensträger um einen König von Umma. Er wäre damit wahrscheinlich der erste Herrscher in Mesopotamien, der durch eine Inschrift aus seiner Regierungszeit belegt ist. Mit diesem Namen lässt sich auch nin-be6-be6 Banca Adab 13 Vs. i 3 (ED IIIb) vergleichen. Der Wechsel en : nin stützt die sumerische Interpretation des Namens und die Lesung be6 gegen die nur in semitischem Kontext gebrauchte Lesung wu. Gegen eine semitische Interpretation spricht auch be6-be6 UET II 171 B; 296, da die Wahrscheinlichkeit für einen semitischen Namen in diesen Texten unter einem Prozent liegt1) und der Name auch bei etwas anderer Lesung kein Merkmal hat, das ihn als typisch semitisch ausweisen würde. Eventuell zu vergleichen ist auch be6-be6-mud SF 63 iv 6 (P010654). Wenn so richtig gedeutet, handelt es sich um einen alten sumerischen Namen.²) Es gibt allerdings später einen ähnlichen semitischen oder semitisierten Namen bí-bí-um, z. B. IAS 531 ii 6. ki ki Der älteste Beleg für wu ist wohl à-wu-ur4 IAS 104 (Mitte) = Ebla à-wu-ur , cf. CUSAS 12, S. 197, 215. Diese Schreibung aus einer geographischen Liste in Tell Abū Ṣalābīḫ belegt die Lesung natürlich nicht für das Sumerische oder auch nur für den Süden, wo auch in semitischen Namen wa und wu nicht belegt sind, was im ersteren Fall nicht als Zufall gewertet werden kann (cf.