The First Campaign of Sennacherib, King of Assyria, B.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

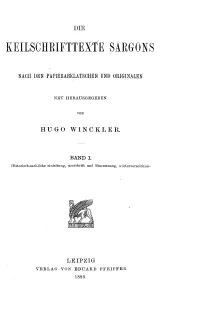

Keilschrifttexte Sargons

DIE KEILSCHRIFTTEXTE SARGONS NACH DEN PAPIERABKLATSCHEN UND ORIGINALEN NEU HERAUSGEGEBEN VON HUGO WINCKLER. BAND I. Historisch-sachliche einleitung, umschrift und ibersetzung, wörterverzeichnis. LEIPZIG VERLAG VON EDUARD PFEIFFER 1889. MEINEM VATER JULIUS WINCKLER GEWIDMET. Inhaltsverzeichnis. Seite Vorrede .... I-V Einleitung . .. VI-XLVI Die inschriften. Die Annalen . .. 1-79 Die Annalen des saales XIV ... .. 80-95 Die prunkinschrift . 96-135 Die inschriften auf dem fuszboden der türen (Pave des portes). I. 136- 138/139 II. 138/139- 142/143 III . .... ........... 142/143-146/147 IV . ............ 146/147-157 V. .. 158- 163 Die inschrift auf der rückseite der platten . .. 164-167 Nimrüd-inschrift . 168-173 Die inschrift der stele . 174-185 Der bericht über den zug gegen Asdod nach S . .. 186-189 Kleinere inschriften . .. 190-196 Wörterverzeichnis . .. 197-234 Verzeichnis der eigennamen . .. 235-242 Verbesserungen . .. .. 243/244 Vorrede. Die meisten der inschriften Sargons sind uns durch die von P. E. Botta in den jahren 1842-45 zu Khorsabad (jL+L^;. bei Jakut 2,422) nördlich von Mossul veranstalteten ausgrabungen zugänglich geworden. veranlasser und triebfeder des unter- nehmens war Julius Mohl gewesen, der durch die wenigen da- mals in London befindlichen keilinschriftlichen denkmäler und durch die bereits erfolgte entzifferung der altpersischen in- schriften angeregt, Botta ans herz gelegt hatte, die trümmer- hügel des nach den arabischen schriftstellern als stätte Ninives bekannten Mossul zu untersuchen. die nachgrabungen daselbst, bekanntlich später von Layard glücklicher fortgesetzt, wurden indessen von keinem erfolge belohnt, bis Botta auf die aussage eines bauern hin, dass in dem etwa acht stunden weiter nörd- lich gelegenen dorfe Khorsabad beschriebene steine in menge gefunden würden, dort zu graben anfing. -

2210 Bc 2200 Bc 2190 Bc 2180 Bc 2170 Bc 2160 Bc 2150 Bc 2140 Bc 2130 Bc 2120 Bc 2110 Bc 2100 Bc 2090 Bc

2210 BC 2200 BC 2190 BC 2180 BC 2170 BC 2160 BC 2150 BC 2140 BC 2130 BC 2120 BC 2110 BC 2100 BC 2090 BC Fertile Crescent Igigi (2) Ur-Nammu Shulgi 2192-2190BC Dudu (20) Shar-kali-sharri Shu-Turul (14) 3rd Kingdom of 2112-2095BC (17) 2094-2047BC (47) 2189-2169BC 2217-2193BC (24) 2168-2154BC Ur 2112-2004BC Kingdom Of Akkad 2234-2154BC ( ) (2) Nanijum, Imi, Elulu Imta (3) 2117-2115BC 2190-2189BC (1) Ibranum (1) 2180-2177BC Inimabakesh (5) Ibate (3) Kurum (1) 2127-2124BC 2113-2112BC Inkishu (6) Shulme (6) 2153-2148BC Iarlagab (15) 2121-2120BC Puzur-Sin (7) Iarlaganda ( )(7) Kingdom Of Gutium 2177-2171BC 2165-2159BC 2142-2127BC 2110-2103BC 2103-2096BC (7) 2096-2089BC 2180-2089BC Nikillagah (6) Elulumesh (5) Igeshaush (6) 2171-2165BC 2159-2153BC 2148-2142BC Iarlagash (3) Irarum (2) Hablum (2) 2124-2121BC 2115-2113BC 2112-2110BC ( ) (3) Cainan 2610-2150BC (460 years) 2120-2117BC Shelah 2480-2047BC (403 years) Eber 2450-2020BC (430 years) Peleg 2416-2177BC (209 years) Reu 2386-2147BC (207 years) Serug 2354-2124BC (200 years) Nahor 2324-2176BC (199 years) Terah 2295-2090BC (205 years) Abraham 2165-1990BC (175) Genesis (Moses) 1)Neferkare, 2)Neferkare Neby, Neferkamin Anu (2) 3)Djedkare Shemay, 4)Neferkare 2169-2167BC 1)Meryhathor, 2)Neferkare, 3)Wahkare Achthoes III, 4)Marykare, 5)............. (All Dates Unknown) Khendu, 5)Meryenhor, 6)Neferkamin, Kakare Ibi (4) 7)Nykare, 8)Neferkare Tereru, 2167-2163 9)Neferkahor Neferkare (2) 10TH Dynasty (90) 2130-2040BC Merenre Antyemsaf II (All Dates Unknown) 2163-2161BC 1)Meryibre Achthoes I, 2)............., 3)Neferkare, 2184-2183BC (1) 4)Meryibre Achthoes II, 5)Setut, 6)............., Menkare Nitocris Neferkauhor (1) Wadjkare Pepysonbe 7)Mery-........, 8)Shed-........, 9)............., 2183-2181BC (2) 2161-2160BC Inyotef II (-1) 2173-2169BC (4) 10)............., 11)............., 12)User...... -

Assyrian Historiography and Liguistics

ASSYRIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY A SOURCE STUDY THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI STUDIES SOCIAL SCIENCE SERIES VOLUME III NUMBER 1 ASSYRIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY A Source Study By ALBERT TEN EYCK OLMSTEAD Associate Professor of Ancient History Assyrian International News Agency Books Online www.aina.org CONTENTS CHAPTER I Assyrian Historians and their Histories CHAPTER II The Beginnings of True History (Tiglath Pileser I) CHAPTER III The Development of Historical Writing (Ashur nasir apal and Shalmaneser III) CHAPTER IV Shamshi Adad and the Synchronistic History CHAPTER V Sargon and the Modern Historical Criticism CHAPTER VI Annals and Display Inscriptions (Sennacherib and Esarhaddon) CHAPTER VII Ashur bani apal and Assyrian Editing CHAPTER VIII The Babylonian Chronicle and Berossus CHAPTER I ASSYRIAN HISTORIANS AND THEIR HISTORIES To the serious student of Assyrian history, it is obvious that we cannot write that history until we have adequately discussed the sources. We must learn what these are, in other words, we must begin with a bibliography of the various documents. Then we must divide them into their various classes, for different classes of inscriptions are of varying degrees of accuracy. Finally, we must study in detail for each reign the sources, discover which of the various documents or groups of documents are the most nearly contemporaneous with the events they narrate, and on these, and on these alone, base our history of the period. To the less narrowly technical reader, the development of the historical sense in one of the earlier culture peoples has an interest all its own. The historical writings of the Assyrians form one of the most important branches of their literature. -

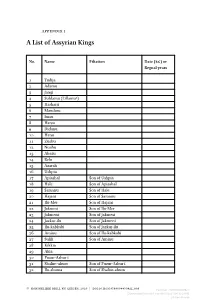

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years -

Assyrian Period (Ca. 1000•fi609 Bce)

CHAPTER 8 The Neo‐Assyrian Period (ca. 1000–609 BCE) Eckart Frahm Introduction This chapter provides a historical sketch of the Neo‐Assyrian period, the era that saw the slow rise of the Assyrian empire as well as its much faster eventual fall.1 When the curtain lifts, at the close of the “Dark Age” that lasted until the middle of the tenth century BCE, the Assyrian state still finds itself in the grip of the massive crisis in the course of which it suffered significant territorial losses. Step by step, however, a number of assertive and ruthless Assyrian kings of the late tenth and ninth centuries manage to reconquer the lost lands and reestablish Assyrian power, especially in the Khabur region. From the late ninth to the mid‐eighth century, Assyria experiences an era of internal fragmentation, with Assyrian kings and high officials, the so‐called “magnates,” competing for power. The accession of Tiglath‐pileser III in 745 BCE marks the end of this period and the beginning of Assyria’s imperial phase. The magnates lose much of their influence, and, during the empire’s heyday, Assyrian monarchs conquer and rule a territory of unprecedented size, including Babylonia, the Levant, and Egypt. The downfall comes within a few years: between 615 and 609 BCE, the allied forces of the Babylonians and Medes defeat and destroy all the major Assyrian cities, bringing Assyria’s political power, and the “Neo‐Assyrian period,” to an end. What follows is a long and shadowy coda to Assyrian history. There is no longer an Assyrian state, but in the ancient Assyrian heartland, especially in the city of Ashur, some of Assyria’s cultural and religious traditions survive for another 800 years. -

The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State D

Cambridge University Press 0521563585 - The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State D. T. Potts Index More information INDEX A’abba, 179 Aleppo, 169, 170 Apollophanos, 364, 369 Aahitek, 207, 208 Alexander, the Great, 348–50, apples, 137 Abadan, 14 355; I Balas, 373, 383, 387, 388 Arahir, 136 Aba-Enlilgim, 140 al-Hiba, 92, 95 Aramaic, 384, 399, 424 Abalgamash, 105, 106 Ali Kosh, see Tepe Ali Kosh Arashu, 285 Abbashaga, 135, 140 Allabria, 263 Arawa, 89; see also Urua Ab-i-Diz, see Diz Allahad, 168 Arbimazbi, 140 Ab-i-Marik, 22 almond, 155 Archalos, 349 Abiradu, 328 Altyn-depe, 118 archons, at Susa, 363 Abu Fanduweh, 55 Alumiddatum, 136, 138, 141 Ardashir, 410–16, Fig. 11.2 Abu Salabikh, 58, 88, 242 Amar-Sin, 135, 137, Areia, 323 Abulites, 348–50 ambassadors, 138–9 Argishti-henele, 301 Aburanum, 137 amber, 33 Ariaramnes, 287 accountancy, 59–60 Amedirra, 283 Arjan, 124, 303–6, 412 Achaemenes, 287 Amel-Marduk, 293 armour, 203, 277 Açina, 317–18 Ammiditana, 171 aromatics, see incense Acropole, see Susa, Acropole Ammisaduqa, 165, 189 Arrapha/Arraphe, 242 Acts, Book of (2.9), 3 Amorites, 167 arrowheads, copper/bronze, 95 Adab, 121 Ampe, 391 Arsaces, 376–7, 388, 391, 392 Adad, 347 Ampirish, 306 Arsames, 287 Adad-erish, 204 Amurru, 193 arsenic, 218 Adad-nirari III, 263 Amygdalus, 23 Artabanus I, 391; II, 391; III, 369; Adad-rabi, 177 An(?)turza, 347 IV, 401, 412 Adad-sharru-rabu, 191 Anahita, 383 Artaxerxes I, 335, 337, 318; II, 7, Adad-shuma-iddina, 231 Anarak, 33, 34 335, 337, 359; III, 339 Adad-shuma-usur, -

Asurluların Kanunları Sümer Ve Hammurabi Kanunlarına Göre Çok Daha Sert Hükümler Içeriyordu

YUNAN ANADOLU İRAN MISIR HİNT Sümerler (M.Ö.4000-2350): –İlk defa yazıyı kullandılar (M.Ö.3200). –İlk siyasal örgütlenme Site şehir devletleri oluşturuldu. (Ur, Uruk, Kiş, Lagaş) –İlk yazılı kanunları yapmışlardır. (Lagaş kralı Urgakina) (İlk hukuk devletidir.) GENEL ÖZELLİKLERİ: Genellikle iklim ve yer şekillerinin uygun olduğu su kenarlarında kurulmuşlardır. • Daha çok tarıma dayalı üretim vardır. • Genellikle site (kent) devleti biçiminde oluşmuşlardır.(Polis, Nom, Site) •Çok tanrılı din yaygındır.(ilk tek tanrılı din İbranilerdedir) Yönetim anlayışları tanrısal (teokratik) –Bütünüyle tanrısal: Mısır (tanrı kral) –Yarı tanrısal: Mezopotamya (rahip kral) Sümerler –Bir yılı 354 gün olarak hesaplamışlar ve ay yılı takviminin temelini atmışlardır. –Ziggurat adında tapınaklar yapmışlar. Son katı gözlemevi olmuş ve astronomi gelişmiştir. –En önemli mülkiyet, su kanalları ve topraktır. –Patesi denilen Rahip Kralları vardır. – Sümer kanunları fidye, Hammurabi kanunları kısasa dayalıdır. – Sümer kanunları şehir veya küçük bir bölgeyi idare etmek, Babil ve Asur kanunları ise büyük bir ülke veya devleti idare etmek için yapılmıştır(Merkeziyetçi olmak için). KISAS: Suç için verilen cezanın da aynı oranda ağır olması sistemidir. Kanunların sert olması suç oranını azaltıp, devletin daha uzun süre yaşamasını sağlamak içindir. ZİGGURAT TAPINAKLAR • Anu veya An: Gök tanrısı, önceleri baş tanrıyken sonra yerini hava tanrısı Enlil almıştır. • Enlil: Hava tanrısı, tanrıların babası, tapınağı Ekur Nippur kentindeydi. • Enki: Bilgelik tanrısı • Nimmah (Ninhursag): -

Appendix Epsilon

Appendix Epsilon: The Pavia Intellectual Line Connecting brothers of Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity at Cornell University, tracing their fraternal Big Brother/Little Brother line to tri-Founder John Andrew Rea (1869) John Andrew Rea, tri-founder of Phi Kappa Psi at Cornell . . was advised by Andrew Dickson White, . Olybrius was nephew to Flavius President of Cornell . Maximus . who was lectured by, and referred Jack . Flavius Maximus was grandson to Sextus Rea to, Washington Irving . Probus . and then through the Halle line, Appendix . Sextus Probus was son-in-law and first Delta, to the University of Pavia . cousin to Quintus Olybrius . . Pavia was elevated by the Carolingian . Quintus Olybrius was the son of to Clodius Emperor Lothair . Celsinus Adelphus spouse to Faltonia Betitia Proba . whose grandfather deposed the last . all of the above were Neo-Platonists in the Lombardic king Desiderius . tradition of Plotinus . who ruled in succession to the founder of . Plotimus was a student of Ammonius, he of his dynasty, Alboin . Numenius, he of Pythagoras, he of Pherecydes . Alboin forcefully married Rosamund, . Pythagoras also studied under princess of the Gepids . Anaximenes, he under Anaximander, he under Thales . Rosamund was daugther to Cunimund, last . king of the Gepids. Thales studied in the school of Egyption priest Petiese, who was invested by king Psamtik . the story of Cunimund’s court was . who served under Assyria king preserved by Cassiodorus . Esarhaddon, successor to Sennencherib . . Cassiodorus succeeded Boethius as first . successor to the two Sargons . Minister to the Ostrogoths . Boethius was grandson of Emperor Olybrius . Below we present short biographies of the Pavia intellectual line of the Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity at Cornell University. -

A Contribution to Ancient Near Eastern Chronology (C. 1600 – 900 BC)

A Contribution to Ancient Near Eastern Chronology (c. 1600 – 900 BC) Methodology Core Hypotheses Major Historical Repercussions 1 Methodology: Theory of Paradigms T. Kuhn (1962), The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Paradigm definition: ‘universally recognized scientific achievements that for a time provide model problems and solutions to a community of practitioners’ (e.g. Ptolemaic astronomy vs. Copernican astronomy; Creation-evolution vs. Darwinian evolution; etc.). 2 Paradigm Change Requirements of successful new paradigms: Resolve anomalies that triggered crisis Preserve most of the puzzle-solving solutions of ‘old’ paradigm. Criteria of good (better) paradigm: Breadth of scope (e.g. chronological/geographic) Accuracy/precision – essential for relating theory to data Consistency Fruitfulness: Integrate currently isolated historical texts Reveal new historical relationships Make testable predictions Simplicity – minimum ‘core’ and ‘subsidiary’ hypotheses. 3 Assyrian Anomalies Shalmaneser II to Adad-nirari II – current anomalies: 1) Ashur-rabi II to Ashur-nirari IV – almost complete lack of contemporary texts (only one exception) 2) Name of Shalmaneser II omitted from the Nassouhi King-list (possibly composed by Ashur-dan II) 3) The entire Assyrian eponym canon contains only three reigns with ‘repetitive eponyms’, i.e., ‘One after PN’ Shalmaneser II (1/12), Ashur-nirari IV (6/6), Tiglath-pileser II (from 3rd eponym) 4) Tiglath-pileser II: Khorsabad King-list (32 years); KAV 22 (33 eponyms) 5) Ashur-dan II to Adad-nirari II; revolutionary change in position of king’s eponym, from 1st to 2nd position 6) Shalmaneser II to Ashur-resha-ishi II; 2 burial stele expected in Ashur (Ashur-nirari IV and Ashur-rabi II), only 1 found. -

The Cuneiform Inscriptions and the Old Testament

g-'A « ?r £*-j'<r.-.?gj:«5?^^x-?^i:^S:?:;**a«%5g'^^^^^ ^ THEOLOGICAL TRANSLATI ON FUNDjLIBRARY. A Series of Translations by which the best results of recent theological investigations on the Continent, conducted without reference to doctrinal con- siderations, and with the sole purpose of arriving at truth, are placed within reach of English readers. Three volumes 8vo. annually for a Guinea Subscription, or a Selection of six or more volumes at js per vol. JL, BAUR (P. C.) Chiu'cii History oi the First Three Cen- turies. Translated from the Third German Edition. Edited by the Rev. Allan Menzies. 2 vols. 8vo. 215. (J2S 2. BAUR (P. C.) Paul, the Apostle of Jesus Christ, his Life and Work, his Epistles and Doctrine. A Contribution to a Critical ^ History of Primitive Christianity. Second Edition. By the Rev. Allan Menzies. 2 vols. 21s. 3. BLEEK'S Lectures on the Apocalypse. Edited by the Rev. Dr. S. Davidson, ios 6d. 4. EWALD (H.) Commentary on the Prophets of the Old Testament. Translated by the Rev. J. Frederick Smith. 5 vols. 8vo. Each IOS 6d. 5. EWALD (H.) Commentary on the Psalms. Translated by the Rev. E. Johnson, m.a. 2 vols. 8vo. Each 105 6d. 6. EWALD (H.) Commentary on the Book of Job, with Trans- lation by Professor H. Ewald. Translated from the German by the Rev. J. Frederick Smith, i vol. Svo. los 6d. 7. HAUSRATH (Professor A.) History of the New Testa- ment Times. The Time of Jesus. By Dr. A. Hausrath, Professor of Theology, Heidelberg. Translated, with the Author's sanction, from the Second German Edition, by the Revs. -

Postgate 1992.Pdf

The Land of Assur and the Yoke of Assur Author(s): J. N. Postgate Source: World Archaeology, Vol. 23, No. 3, Archaeology of Empires (Feb., 1992), pp. 247- 263 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/124761 Accessed: 07-09-2016 19:40 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to World Archaeology This content downloaded from 86.18.92.122 on Wed, 07 Sep 2016 19:40:43 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Land of Assur and the yoke of Assur J. N. Postgate The Assyrian state had its origins early in the second millennium, as the small self-governing merchant city of Assur, became a territorial power in the fourteenth to thirteenth centuries BC, and survived until 605 BC, by which time it had created an empire which set the pattern for its successors: Babylon, Persia and Macedon. Both as a phenomenon in its own right, and as the originator of the Near Eastern style of empire, Assyria demands to be included in any study of empires. -

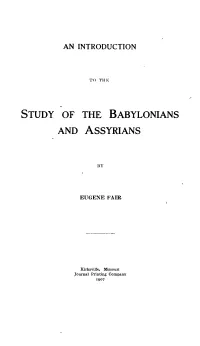

Study of the Babylonians and Assyrians

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF THE BABYLONIANS AND ASSYRIANS BY EUGENE FAIR Kirksville, Missouri Journal Printing Company 1907 PREFACE. The writing of this pamphlet has been brought about wholly by the needs of the ^Titer's classes in Oriental History. So far as he knows, there is no outline of this subject which is suitable to his purposes. The usual w^orks are either too extensive or out-of-date. There is no attempt made at originality. The facts have been di'awn largely from such works as Goodspeed's History of the Babylonians and Assyrians, Rogers' History of Babylonia and Assjrria, Maspero's Life in Ancient Egypt and 4ssyria, Dawn of Civilization, Struggle of the Nations and Pass ing of the Empires; Perrot and Chipiez's History of Art in Chaldea and Assyria; Saj'ce's Babylonians and Assyrians: Clay's Light on the Old Testament from Babel. Special thanks are due to President John R. Kirk, Professor E. M. Violette and Mrs. Fair for consultation and encouragement in many ways. In the body of the text G. stands for Goodspeed's History of the Babylonians and Assyrians. CHAPTER I, NATURAL EXVIRONJIENTS .^ND THK PEOPLE. The dominating physical characteristic of Babylonia and Assyria was the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The most distant sources of these streams are between 38 and 40 de.ijrees North latitude, in the lofty Armenian table-lands which are some 7000 feet above the sea level, while their mouths leading into the Per sian gulf have a North latitude of about 31 degrees. After break ing through the southern border of these table-lands, the one on the eastern, the other on the western edge, both rivers flow south east, generally speaking, through a country whose northern bor der is about 800 miles from the Persian gulf.