Assyrian Historiography and Liguistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2210 Bc 2200 Bc 2190 Bc 2180 Bc 2170 Bc 2160 Bc 2150 Bc 2140 Bc 2130 Bc 2120 Bc 2110 Bc 2100 Bc 2090 Bc

2210 BC 2200 BC 2190 BC 2180 BC 2170 BC 2160 BC 2150 BC 2140 BC 2130 BC 2120 BC 2110 BC 2100 BC 2090 BC Fertile Crescent Igigi (2) Ur-Nammu Shulgi 2192-2190BC Dudu (20) Shar-kali-sharri Shu-Turul (14) 3rd Kingdom of 2112-2095BC (17) 2094-2047BC (47) 2189-2169BC 2217-2193BC (24) 2168-2154BC Ur 2112-2004BC Kingdom Of Akkad 2234-2154BC ( ) (2) Nanijum, Imi, Elulu Imta (3) 2117-2115BC 2190-2189BC (1) Ibranum (1) 2180-2177BC Inimabakesh (5) Ibate (3) Kurum (1) 2127-2124BC 2113-2112BC Inkishu (6) Shulme (6) 2153-2148BC Iarlagab (15) 2121-2120BC Puzur-Sin (7) Iarlaganda ( )(7) Kingdom Of Gutium 2177-2171BC 2165-2159BC 2142-2127BC 2110-2103BC 2103-2096BC (7) 2096-2089BC 2180-2089BC Nikillagah (6) Elulumesh (5) Igeshaush (6) 2171-2165BC 2159-2153BC 2148-2142BC Iarlagash (3) Irarum (2) Hablum (2) 2124-2121BC 2115-2113BC 2112-2110BC ( ) (3) Cainan 2610-2150BC (460 years) 2120-2117BC Shelah 2480-2047BC (403 years) Eber 2450-2020BC (430 years) Peleg 2416-2177BC (209 years) Reu 2386-2147BC (207 years) Serug 2354-2124BC (200 years) Nahor 2324-2176BC (199 years) Terah 2295-2090BC (205 years) Abraham 2165-1990BC (175) Genesis (Moses) 1)Neferkare, 2)Neferkare Neby, Neferkamin Anu (2) 3)Djedkare Shemay, 4)Neferkare 2169-2167BC 1)Meryhathor, 2)Neferkare, 3)Wahkare Achthoes III, 4)Marykare, 5)............. (All Dates Unknown) Khendu, 5)Meryenhor, 6)Neferkamin, Kakare Ibi (4) 7)Nykare, 8)Neferkare Tereru, 2167-2163 9)Neferkahor Neferkare (2) 10TH Dynasty (90) 2130-2040BC Merenre Antyemsaf II (All Dates Unknown) 2163-2161BC 1)Meryibre Achthoes I, 2)............., 3)Neferkare, 2184-2183BC (1) 4)Meryibre Achthoes II, 5)Setut, 6)............., Menkare Nitocris Neferkauhor (1) Wadjkare Pepysonbe 7)Mery-........, 8)Shed-........, 9)............., 2183-2181BC (2) 2161-2160BC Inyotef II (-1) 2173-2169BC (4) 10)............., 11)............., 12)User...... -

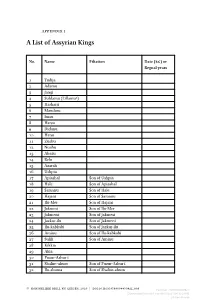

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years -

Assyrian Period (Ca. 1000•fi609 Bce)

CHAPTER 8 The Neo‐Assyrian Period (ca. 1000–609 BCE) Eckart Frahm Introduction This chapter provides a historical sketch of the Neo‐Assyrian period, the era that saw the slow rise of the Assyrian empire as well as its much faster eventual fall.1 When the curtain lifts, at the close of the “Dark Age” that lasted until the middle of the tenth century BCE, the Assyrian state still finds itself in the grip of the massive crisis in the course of which it suffered significant territorial losses. Step by step, however, a number of assertive and ruthless Assyrian kings of the late tenth and ninth centuries manage to reconquer the lost lands and reestablish Assyrian power, especially in the Khabur region. From the late ninth to the mid‐eighth century, Assyria experiences an era of internal fragmentation, with Assyrian kings and high officials, the so‐called “magnates,” competing for power. The accession of Tiglath‐pileser III in 745 BCE marks the end of this period and the beginning of Assyria’s imperial phase. The magnates lose much of their influence, and, during the empire’s heyday, Assyrian monarchs conquer and rule a territory of unprecedented size, including Babylonia, the Levant, and Egypt. The downfall comes within a few years: between 615 and 609 BCE, the allied forces of the Babylonians and Medes defeat and destroy all the major Assyrian cities, bringing Assyria’s political power, and the “Neo‐Assyrian period,” to an end. What follows is a long and shadowy coda to Assyrian history. There is no longer an Assyrian state, but in the ancient Assyrian heartland, especially in the city of Ashur, some of Assyria’s cultural and religious traditions survive for another 800 years. -

The First Campaign of Sennacherib, King of Assyria, B.C

DEDICATED TO MY PARENTS. THE FIRST CAMPAIGN OF SENNACHERIB, KING OF ASSYRIA. (B.C. 703-2.) INTRODUCTION. Cylinder 113203. TnHE text has been copied fromn a hollow barrel cylinder of the usual type, now in thle British Museum. The cylinder is about 9½inches long, the bases being 3- inches in diameter, the diameter of the thickest portion of the barrel about 4½inches, and the perforations of the bases about I inch in diameter. The clay is reddish in colour, and very soft in parts, and owing to this softness the text appears to have suffered damage when the cylinder was discovered. The scribe has not drawn lines across the cylinder, and in conse- quence many of the lines bend considerably. The writing is very neat and clear, and of the same style as other historical inscriptions of the reign. The first 14 lines are written in half lines, that is with a distinct break, as though forming part of a hymn, but from that point to the end the lines are continuous. The first half of thle first 16 lines is badly broken, the fine clay of the surface having been completely removed, perhaps by a blow from a pick. The first 9 lines can be partly restored from Ki. 1902-5-10, 1, a fragment of a barrel cylinder of different shape from No. 113203, which gives beginnings of the first 9 and last 16 lines of a duplicate text. A 2 THE FIRST CAMPAIGN OF SENNACHERIB. Provenance. No information is available as to the site where the cylinder was discovered. -

Asurluların Kanunları Sümer Ve Hammurabi Kanunlarına Göre Çok Daha Sert Hükümler Içeriyordu

YUNAN ANADOLU İRAN MISIR HİNT Sümerler (M.Ö.4000-2350): –İlk defa yazıyı kullandılar (M.Ö.3200). –İlk siyasal örgütlenme Site şehir devletleri oluşturuldu. (Ur, Uruk, Kiş, Lagaş) –İlk yazılı kanunları yapmışlardır. (Lagaş kralı Urgakina) (İlk hukuk devletidir.) GENEL ÖZELLİKLERİ: Genellikle iklim ve yer şekillerinin uygun olduğu su kenarlarında kurulmuşlardır. • Daha çok tarıma dayalı üretim vardır. • Genellikle site (kent) devleti biçiminde oluşmuşlardır.(Polis, Nom, Site) •Çok tanrılı din yaygındır.(ilk tek tanrılı din İbranilerdedir) Yönetim anlayışları tanrısal (teokratik) –Bütünüyle tanrısal: Mısır (tanrı kral) –Yarı tanrısal: Mezopotamya (rahip kral) Sümerler –Bir yılı 354 gün olarak hesaplamışlar ve ay yılı takviminin temelini atmışlardır. –Ziggurat adında tapınaklar yapmışlar. Son katı gözlemevi olmuş ve astronomi gelişmiştir. –En önemli mülkiyet, su kanalları ve topraktır. –Patesi denilen Rahip Kralları vardır. – Sümer kanunları fidye, Hammurabi kanunları kısasa dayalıdır. – Sümer kanunları şehir veya küçük bir bölgeyi idare etmek, Babil ve Asur kanunları ise büyük bir ülke veya devleti idare etmek için yapılmıştır(Merkeziyetçi olmak için). KISAS: Suç için verilen cezanın da aynı oranda ağır olması sistemidir. Kanunların sert olması suç oranını azaltıp, devletin daha uzun süre yaşamasını sağlamak içindir. ZİGGURAT TAPINAKLAR • Anu veya An: Gök tanrısı, önceleri baş tanrıyken sonra yerini hava tanrısı Enlil almıştır. • Enlil: Hava tanrısı, tanrıların babası, tapınağı Ekur Nippur kentindeydi. • Enki: Bilgelik tanrısı • Nimmah (Ninhursag): -

A Contribution to Ancient Near Eastern Chronology (C. 1600 – 900 BC)

A Contribution to Ancient Near Eastern Chronology (c. 1600 – 900 BC) Methodology Core Hypotheses Major Historical Repercussions 1 Methodology: Theory of Paradigms T. Kuhn (1962), The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Paradigm definition: ‘universally recognized scientific achievements that for a time provide model problems and solutions to a community of practitioners’ (e.g. Ptolemaic astronomy vs. Copernican astronomy; Creation-evolution vs. Darwinian evolution; etc.). 2 Paradigm Change Requirements of successful new paradigms: Resolve anomalies that triggered crisis Preserve most of the puzzle-solving solutions of ‘old’ paradigm. Criteria of good (better) paradigm: Breadth of scope (e.g. chronological/geographic) Accuracy/precision – essential for relating theory to data Consistency Fruitfulness: Integrate currently isolated historical texts Reveal new historical relationships Make testable predictions Simplicity – minimum ‘core’ and ‘subsidiary’ hypotheses. 3 Assyrian Anomalies Shalmaneser II to Adad-nirari II – current anomalies: 1) Ashur-rabi II to Ashur-nirari IV – almost complete lack of contemporary texts (only one exception) 2) Name of Shalmaneser II omitted from the Nassouhi King-list (possibly composed by Ashur-dan II) 3) The entire Assyrian eponym canon contains only three reigns with ‘repetitive eponyms’, i.e., ‘One after PN’ Shalmaneser II (1/12), Ashur-nirari IV (6/6), Tiglath-pileser II (from 3rd eponym) 4) Tiglath-pileser II: Khorsabad King-list (32 years); KAV 22 (33 eponyms) 5) Ashur-dan II to Adad-nirari II; revolutionary change in position of king’s eponym, from 1st to 2nd position 6) Shalmaneser II to Ashur-resha-ishi II; 2 burial stele expected in Ashur (Ashur-nirari IV and Ashur-rabi II), only 1 found. -

Postgate 1992.Pdf

The Land of Assur and the Yoke of Assur Author(s): J. N. Postgate Source: World Archaeology, Vol. 23, No. 3, Archaeology of Empires (Feb., 1992), pp. 247- 263 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/124761 Accessed: 07-09-2016 19:40 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to World Archaeology This content downloaded from 86.18.92.122 on Wed, 07 Sep 2016 19:40:43 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Land of Assur and the yoke of Assur J. N. Postgate The Assyrian state had its origins early in the second millennium, as the small self-governing merchant city of Assur, became a territorial power in the fourteenth to thirteenth centuries BC, and survived until 605 BC, by which time it had created an empire which set the pattern for its successors: Babylon, Persia and Macedon. Both as a phenomenon in its own right, and as the originator of the Near Eastern style of empire, Assyria demands to be included in any study of empires. -

Study of the Babylonians and Assyrians

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF THE BABYLONIANS AND ASSYRIANS BY EUGENE FAIR Kirksville, Missouri Journal Printing Company 1907 PREFACE. The writing of this pamphlet has been brought about wholly by the needs of the ^Titer's classes in Oriental History. So far as he knows, there is no outline of this subject which is suitable to his purposes. The usual w^orks are either too extensive or out-of-date. There is no attempt made at originality. The facts have been di'awn largely from such works as Goodspeed's History of the Babylonians and Assyrians, Rogers' History of Babylonia and Assjrria, Maspero's Life in Ancient Egypt and 4ssyria, Dawn of Civilization, Struggle of the Nations and Pass ing of the Empires; Perrot and Chipiez's History of Art in Chaldea and Assyria; Saj'ce's Babylonians and Assyrians: Clay's Light on the Old Testament from Babel. Special thanks are due to President John R. Kirk, Professor E. M. Violette and Mrs. Fair for consultation and encouragement in many ways. In the body of the text G. stands for Goodspeed's History of the Babylonians and Assyrians. CHAPTER I, NATURAL EXVIRONJIENTS .^ND THK PEOPLE. The dominating physical characteristic of Babylonia and Assyria was the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The most distant sources of these streams are between 38 and 40 de.ijrees North latitude, in the lofty Armenian table-lands which are some 7000 feet above the sea level, while their mouths leading into the Per sian gulf have a North latitude of about 31 degrees. After break ing through the southern border of these table-lands, the one on the eastern, the other on the western edge, both rivers flow south east, generally speaking, through a country whose northern bor der is about 800 miles from the Persian gulf. -

Head Heart Hands

Lesson 6 (Part 2) - Nahum Facilitator’s Note In this lesson we will explore the prophecy of Nahum. Called a vision, Nahum’s message is addressed solely to Nineveh, the capital city of the Assyrian Empire, which had expanded its reach throughout much of the known world through violent and cruel military conquests. Nahum’s message recounts the vision he received from God in which he witnessed Nineveh’s downfall via a swift and violent attack from her enemies. Approximately 150 years earlier (circa 780-750 B.C.), God had sent the prophet Jonah to preach to the Ninevites and warn them of their impending destruction unless they repented. Nineveh responded, and God forgave them. Not so in Nahum. The vision is fully devoted to the announcement of Nineveh’s doom, and comfort for Judah who will no longer be subject to Assyrian oppression. Nineveh’s idolatry, violence and cruelty have pushed her past the point of no return; God’s patience with her is at an end and His wrath will now be poured out on her until she is utterly destroyed, never to rise again. Through this lesson we hope to provide material that will provide knowledge (HEAD); then ask questions that will bring us understanding (HEART); and then motivate participants to go and live the Word in the world and demonstrate Godly wisdom (HANDS). HEAD ➨ HEART❤ ➨ HANDS We hope that by this study your class participants will not only hear, know, and understand the Word, but that they will also be driven to become the “Living Word” to the world around us. -

Assyria; Its Princes, Priests and People

MIONOLITIHIOF SHAILM\NLIESER It. (Fr.-m the ogiiw in the S, iliif,, i;B^atI of st~ilre noWclige. VII. ASSYRIA ITS PRINCES, PRIESTS, AND PEOPLE. BY A. H. SAYCE, M.A. DEPUTY PROFESSOR OF COMPARATIVE PHILOLOGY, OXFORD, HON. LL.D. DUBLIN, ETC AUTHOR OF 'FRESH LIGHT FROM THE ANCIENT MONUMENTS,' 'AN INTRODUCTION TO EZRA, NEHEMIAH, AND ESTHER,' ETC. LONDON: THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY, 56, PATERNOSTER Row, AND 65, ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD. 1895. FIRST EDITION, JULY, 1885. REPRINTED, OCTOBER, 1887; NOVEMBER, 1889; OCTOBER, 189I; TUNE, 1893; AUGUST, I895. CO NTENTS. CHAPTER I. PAGE The Country and People 0... .·..· 2 1 CHAPTER II. Assyrian History... ...· ... ... ... ... 27 CHAPTER II. Assyrian Religion ..· ·...· ... .....* 55 CHAPTER IV. Art, Literature, and Science ..... ... .. 86 CHAPTER V. -Manners and Customs; Trade and Government ·.. 122 ILLUSTRATIONS. PAGE Monolith of Shalmaneser II (from the original in the British Museum)-Frontispiece. Assurbani-pal and his Queen (from the original in the British Museum) ... ... ..... 49 Nergal (from the original in the British Museum) ... 65 Fragment now in the British Museum showing Primitive Hieroglyphics and Cuneiform Characters side by side 92 An Assyrian Book (from the original in the British Museum) .................. 98 Part of an Assyrian Cylinder containing Hezekiah's Name (from the original in the British Museum) ... 04 Assyrian King in his Chariot ... ... ... 25 Siege of a City ... .... ,,. .. ... i271.-- PR EFACE. AMONG the many wonderful achievements of the present century there is none more wonderful than the recovery and decipherment of the monuments of ancient-Nineveh. For generations the great oppressing city had slept buried beneath the fragments of its own ruins, its his- tory lost, its very site forgotten. -

![Assyrian Historiography [With Accents] 1 Assyrian Historiography [With Accents]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1753/assyrian-historiography-with-accents-1-assyrian-historiography-with-accents-6281753.webp)

Assyrian Historiography [With Accents] 1 Assyrian Historiography [With Accents]

Assyrian Historiography [with accents] 1 Assyrian Historiography [with accents] Project Gutenberg's Assyrian Historiography, by Albert Ten Eyck Olmstead Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Assyrian Historiography Author: Albert Ten Eyck Olmstead Release Date: September, 2004 [EBook #6559] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on December 28, 2002] Edition: 10 Language: English CHAPTER I 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ASSYRIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY *** Produced by Arno Peters, David Moynihan Charles Franks and the Online Distributed Proofing Team. ASSYRIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY A SOURCE STUDY THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI STUDIES SOCIAL -

Azariah of Judah and Tiglath-Pileser III Author(S): Howell M

Azariah of Judah and Tiglath-Pileser III Author(s): Howell M. Haydn Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 28, No. 2 (1909), pp. 182-199 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4617145 Accessed: 12/03/2010 15:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sbl. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org 182 JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE Azariah of Judah and Tiglath-pileser III HOWELL M.