Representations of Rebellion in the Assyrian Royal Inscriptions by Benjamin Neil Dewar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Babylonia

K- A -AHI BLACK STONE CONTRACT TABLET O F MARU DU N DIN , 6 page 9 . ANCIENT HISTORY FROM THE MONUMENTS. THE F BABYL I HISTORY O ONA, BY TH E LATE I GEO RGE S M TH, ES Q. , F T E EPA TM EN EN N I U IT ES B T S M E M O H T O F O I T T I I I H US U . D R R AL A Q , R ED ITED BY R EV. A . H . SAY CE, SSIST O E OR F C MP T VE P Y O O D NT P R F S S O O I HI O OG XF R . A A ARA L L , PU BLISHED U NDER THE DIRECTION O F THE COMM ITTEE O F GENERAL LITERATURE AND ED UCATION APPOINTED BY THE SOCIETY FO R PROMOTING CH ISTI N K NOW E G R A L D E. LO NDON S O IETY F R P ROMOTING C H RI TI N NO C O S A K WLEDGE . SOLD A T THE DEPOSITORIES ’ G E T U EEN ST EET LINCO LN s-INN ExE 77, R A Q R , LDs ; OY EXCH N G E 8 PICC I Y 4, R AL A ; 4 , AD LL ; A ND B OO KSE E S ALL LL R . k t New Y or : P o t, Y oung, Co. LONDON WY M N A ND S ONS rm NTERs G E T UEEN ST EET A , , R A Q R , ' LrNCOLN s - xNN FIE DS w L . -

Considering a Future in Syria and the Protection of the Right to Culture

THE JOHN MARSHALL REVIEW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW BEYOND THE DESTRUCTION OF SYRIA: CONSIDERING A FUTURE IN SYRIA AND THE PROTECTION OF THE RIGHT TO CULTURE SARAH DÁVILA-RUHAAK ABSTRACT Although the right to culture has been widely recognized under international human rights, its reach and practical application has been limited in cultural preservation efforts. Individuals and communities that attempt to be part of the decision-making process in preservation efforts often face barriers to access in that process. The need to re-conceptualize the right to culture is vital for its protection and preservation. This article proposes that the right to self-determination must be utilized as a core fundamental principle that enables a disenfranchised individual or community to have ownership in preservation efforts and decide how to shape their identity. It further illustrates how incorporating the “ownership” element of the right to self- determination will strengthen the application of the right to culture in preservation efforts. The article utilizes the destruction of Syrian cultural heritage to discuss the need for further protections under international human rights law. Because Syrian cultural heritage is in peril, it is imperative that the right to culture of Syrians is strengthened for the survival of their culture and identity. Syrian cultural heritage must be preserved by the Syrians and for the Syrians, thus allowing them to directly shape who they are as a people. Copyright © 2016 The John Marshall Law School Cite as Sarah Dávila-Ruhaak, Beyond the Destruction of Syria: Considering a Future in Syria and the Protection of the Right to Culture, 15 J. -

Questions for History of Ancient Mesopotamia by Alexis Castor

www.YoYoBrain.com - Accelerators for Memory and Learning Questions for History of Ancient Mesopotamia by Alexis Castor Category: Rise of Civilization - Part 1 - (26 questions) Indentify Uruk Vase - oldest known depiction of gods and humans. 3000 B.C. What 2 mountain ranges frame Mesopotamia Zagros Mountains to the east Taurus Mountains to the north When was writing developed in ancient late 4th millenium B.C. Mesopotamia Identify creature: lamassu - Assyrian mythical creature During the 3rd and 2nd millenium B.C. what north - Akkad were the 2 major regions of north and south south - Sumer Mesopotamia called? When did Hammurabi the law giver reign? 1792 - 1750 B.C. What work of fiction did Ctesias, 4th century account of fictional ruler called B.C. Greek, invent about Mesopotamia Sardanapalus, whose empire collapsed due to self-indulgence What does painting refer to: Death of Sardanapalus by Eugene Delacroix in 1827 refers to mythical ruler of Mesopotamia that 4th Century Greek Ctesias invented to show moral rot of rulers from there Who was: Semiramis written about by Diodorus of Greece in 1st century B.C. queen of Assyria and built Bablyon different lover every night that she killed next day mythical Identify ruins: Nineveh of Assyria Identify: 5th century B.C. inscription of Darius I carved in mountainside at Behistun in Iran Identify: Ishtar Gate from Babylon now located in Berlin Identify the ruin: city of Ur in southern Mesopotamia Define: surface survey where archeologist map physical presence of settlements over an area Define: stratigraphy study of different layers of soil in archeology Define: tell (in archaeology) a mound that build up over a period of human settlement Type of pottery: Halaf - salmon colored clay, painted in red and black, geometric and animal designs When was wine first available to upper around 3100 B.C. -

2210 Bc 2200 Bc 2190 Bc 2180 Bc 2170 Bc 2160 Bc 2150 Bc 2140 Bc 2130 Bc 2120 Bc 2110 Bc 2100 Bc 2090 Bc

2210 BC 2200 BC 2190 BC 2180 BC 2170 BC 2160 BC 2150 BC 2140 BC 2130 BC 2120 BC 2110 BC 2100 BC 2090 BC Fertile Crescent Igigi (2) Ur-Nammu Shulgi 2192-2190BC Dudu (20) Shar-kali-sharri Shu-Turul (14) 3rd Kingdom of 2112-2095BC (17) 2094-2047BC (47) 2189-2169BC 2217-2193BC (24) 2168-2154BC Ur 2112-2004BC Kingdom Of Akkad 2234-2154BC ( ) (2) Nanijum, Imi, Elulu Imta (3) 2117-2115BC 2190-2189BC (1) Ibranum (1) 2180-2177BC Inimabakesh (5) Ibate (3) Kurum (1) 2127-2124BC 2113-2112BC Inkishu (6) Shulme (6) 2153-2148BC Iarlagab (15) 2121-2120BC Puzur-Sin (7) Iarlaganda ( )(7) Kingdom Of Gutium 2177-2171BC 2165-2159BC 2142-2127BC 2110-2103BC 2103-2096BC (7) 2096-2089BC 2180-2089BC Nikillagah (6) Elulumesh (5) Igeshaush (6) 2171-2165BC 2159-2153BC 2148-2142BC Iarlagash (3) Irarum (2) Hablum (2) 2124-2121BC 2115-2113BC 2112-2110BC ( ) (3) Cainan 2610-2150BC (460 years) 2120-2117BC Shelah 2480-2047BC (403 years) Eber 2450-2020BC (430 years) Peleg 2416-2177BC (209 years) Reu 2386-2147BC (207 years) Serug 2354-2124BC (200 years) Nahor 2324-2176BC (199 years) Terah 2295-2090BC (205 years) Abraham 2165-1990BC (175) Genesis (Moses) 1)Neferkare, 2)Neferkare Neby, Neferkamin Anu (2) 3)Djedkare Shemay, 4)Neferkare 2169-2167BC 1)Meryhathor, 2)Neferkare, 3)Wahkare Achthoes III, 4)Marykare, 5)............. (All Dates Unknown) Khendu, 5)Meryenhor, 6)Neferkamin, Kakare Ibi (4) 7)Nykare, 8)Neferkare Tereru, 2167-2163 9)Neferkahor Neferkare (2) 10TH Dynasty (90) 2130-2040BC Merenre Antyemsaf II (All Dates Unknown) 2163-2161BC 1)Meryibre Achthoes I, 2)............., 3)Neferkare, 2184-2183BC (1) 4)Meryibre Achthoes II, 5)Setut, 6)............., Menkare Nitocris Neferkauhor (1) Wadjkare Pepysonbe 7)Mery-........, 8)Shed-........, 9)............., 2183-2181BC (2) 2161-2160BC Inyotef II (-1) 2173-2169BC (4) 10)............., 11)............., 12)User...... -

Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eoN - Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa University of Copenhagen Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Gaspa, Salvatore, "Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eN o-Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 3. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The Neo- Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa, University of Copenhagen In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. -

DESENVOLVIMENTO DO ESQUEMA DECORATIVO DAS SALAS DO TRONO DO PERÍODO NEO-ASSÍRIO (934-609 A.C.): IMAGEM TEXTO E ESPAÇO COMO VE

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO MUSEU DE ARQUEOLOGIA E ETNOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARQUEOLOGIA DESENVOLVIMENTO DO ESQUEMA DECORATIVO DAS SALAS DO TRONO DO PERÍODO NEO-ASSÍRIO (934-609 a.C.): IMAGEM TEXTO E ESPAÇO COMO VEÍCULOS DA RETÓRICA REAL VOLUME I PHILIPPE RACY TAKLA Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arqueologia do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Mestre em Arqueologia. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. ELAINE FARIAS VELOSO HIRATA Linha de Pesquisa: REPRESENTAÇÕES SIMBÓLICAS EM ARQUEOLOGIA São Paulo 2008 RESUMO Este trabalho busca a elaboração de um quadro interpretativo que possibilite analisar o desenvolvimento do esquema decorativo presente nas salas do trono dos palácios construídos pelos reis assírios durante o período que veio a ser conhecido como neo- assírio (934 – 609 a.C.). Entendemos como esquema decorativo a presença de imagens e textos inseridos em um contexto arquitetural. Temos por objetivo demonstrar que a evolução do esquema decorativo, dada sua importância como veículo da retórica real, reflete a transformação da política e da ideologia imperial, bem como das fronteiras do império, ao longo do período neo-assírio. Palavras-chave: Assíria, Palácio, Iconografia, Arqueologia, Ideologia. 2 ABSTRACT The aim of this work is the elaboration of a interpretative framework that allow us to analyze the development of the decorative scheme of the throne rooms located at the palaces built by the Assyrians kings during the period that become known as Neo- Assyrian (934 – 609 BC). We consider decorative scheme as being the presence of texts and images in an architectural setting. -

Assyrian Historiography and Liguistics

ASSYRIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY A SOURCE STUDY THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI STUDIES SOCIAL SCIENCE SERIES VOLUME III NUMBER 1 ASSYRIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY A Source Study By ALBERT TEN EYCK OLMSTEAD Associate Professor of Ancient History Assyrian International News Agency Books Online www.aina.org CONTENTS CHAPTER I Assyrian Historians and their Histories CHAPTER II The Beginnings of True History (Tiglath Pileser I) CHAPTER III The Development of Historical Writing (Ashur nasir apal and Shalmaneser III) CHAPTER IV Shamshi Adad and the Synchronistic History CHAPTER V Sargon and the Modern Historical Criticism CHAPTER VI Annals and Display Inscriptions (Sennacherib and Esarhaddon) CHAPTER VII Ashur bani apal and Assyrian Editing CHAPTER VIII The Babylonian Chronicle and Berossus CHAPTER I ASSYRIAN HISTORIANS AND THEIR HISTORIES To the serious student of Assyrian history, it is obvious that we cannot write that history until we have adequately discussed the sources. We must learn what these are, in other words, we must begin with a bibliography of the various documents. Then we must divide them into their various classes, for different classes of inscriptions are of varying degrees of accuracy. Finally, we must study in detail for each reign the sources, discover which of the various documents or groups of documents are the most nearly contemporaneous with the events they narrate, and on these, and on these alone, base our history of the period. To the less narrowly technical reader, the development of the historical sense in one of the earlier culture peoples has an interest all its own. The historical writings of the Assyrians form one of the most important branches of their literature. -

Women and Their Agency in the Neo-Assyrian Empire

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto WOMEN AND THEIR AGENCY IN THE NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE Assyriologia Pro gradu Saana Teppo 1.2.2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements................................................................................................................5 1. INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................6 1.1 Aim of the study...........................................................................................................6 1.2 Background ..................................................................................................................8 1.3 Problems with sources and material.............................................................................9 1.3.1 Prosopography of the Neo-Assyrian Empire ......................................................10 1.3.2 Corpus of Neo-Assyrian texts .............................................................................11 2. THEORETICAL APPROACH – EMPOWERING MESOPOTAMIAN WOMEN.......13 2.1 Power, agency and spheres of action .........................................................................13 2.2 Women studies and women’s history ........................................................................17 2.3 Feminist scholarship and ancient Near East studies ..................................................20 2.4 Problems relating to women studies of ancient Near East.........................................24 -

Arameans in the Neo-Assyrian Empire

Arameans in the Neo-Assyrian Empire: Approaching Ethnicity and Groupness with Social Network Analysis Repekka Uotila MA thesis Assyriology Instructors: Saana Svärd and Tero Alstola Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki May 2021 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Humanistinen tiedekunta Tekijä – Författare – Author Uotila Aino Selma Repekka Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Arameans in the Neo-Assyrian Empire: Approaching Ethnicity and Groupness with Social Network Analysis Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Assyriologia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages pro gradu -tutkielma year 80 liitteineen, 60 ilman liitteitä toukokuu 2021 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Uusassyrialaisen historian aikana assyrialaiset viittasivat kymmeniin eri ryhmiin ”aramealaisina”. Akkadinkielisen termin semanttinen merkitys muuttuu vuosisatojen aikana, kunnes 600-luvun assyrialaisissa lähteissä sitä ei enää juuri käytetä etnonyyminä. Tutkin työssäni, miten perusteltua on olettaa aramealaisten edustavan yhtenäistä etnistä ryhmää 600-luvulla eaa. Tutkimus olettaa, että sekä ryhmän ulkopuoliset, että siihen kuuluvat tunnistavat, kuka on ryhmän jäsen. Mikäli aramealaiset Assyrialaisessa imperiumissa kokivat edustavansa etnistä vähemmistöä ja ”assyrialaisiin” kuulumatonta väestöä, myös heidän sosiaaliset ryhmänsä todennäköisesti sisältäisivät lähinnä muita aramealaisia. Toteutan tutkimuksen sosiaalisen verkostoanalyysin (social network analysis) avulla. Käytän materiaalina Ancient Near Eastern -

“Going Native: Šamaš-Šuma-Ukīn, Assyrian King of Babylon” Iraq

IRAQ (2019) Page 1 of 22 Doi:10.1017/irq.2019.1 1 GOING NATIVE: ŠAMAŠ-ŠUMA-UKĪN, ASSYRIAN KING OF BABYLON By SHANA ZAIA1 Šamaš-šuma-ukīn is a unique case in the Neo-Assyrian Empire: he was a member of the Assyrian royal family who was installed as king of Babylonia but never of Assyria. Previous Assyrian rulers who had control over Babylonia were recognized as kings of both polities, but Šamaš-šuma-ukīn’s father, Esarhaddon, had decided to split the empire between two of his sons, giving Ashurbanipal kingship over Assyria and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn the throne of Babylonia. As a result, Šamaš-šuma-ukīn is an intriguing case-study for how political, familial, and cultural identities were constructed in texts and interacted with each other as part of royal self- presentation. This paper shows that, despite Šamaš-šuma-ukīn’s familial and cultural identity as an Assyrian, he presents himself as a quintessentially Babylonian king to a greater extent than any of his predecessors. To do so successfully, Šamaš-šuma-ukīn uses Babylonian motifs and titles while ignoring the Assyrian tropes his brother Ashurbanipal retains even in his Babylonian royal inscriptions. Introduction Assyrian kings were recognized as rulers in Babylonia starting in the reign of Tiglath-pileser III (744– 727 BCE), who was named as such in several Babylonian sources including a king list, a chronicle, and in the Ptolemaic Canon.2 Assyrian control of the region was occasionally lost, such as from the beginning until the later years of Sargon II’s reign (721–705 BCE) and briefly towards the beginning of Sennacherib’s reign (704–681 BCE), but otherwise an Assyrian king occupying the Babylonian throne as well as the Assyrian one was no novelty by the time of Esarhaddon’s kingship (680–669 BCE). -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

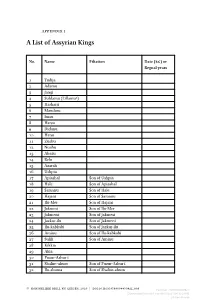

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years -

The Impact of the Arab Conquest on Late Roman Settlementin Egypt

Pýý.ý577 THE IMPACT OF THE ARAB CONQUEST ON LATE ROMAN SETTLEMENTIN EGYPT VOLUME I: TEXT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY CAMBRIDGE This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Cambridge, March 2002 ALISON GASCOIGNE DARWIN COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE For my parents with love and thanks Abstract The Impact of the Arab Conquest on Late Roman Settlement in Egypt Alison Gascoigne, Darwin College The Arab conquest of Egypt in 642 AD affected the development of Egyptian towns in various ways. The actual military struggle, the subsequent settling of Arab tribes and changes in administration are discussed in chapter 1, with reference to specific sites and using local archaeological sequences. Chapter 2 assesseswhether our understanding of the archaeological record of the seventh century is detailed enough to allow the accurate dating of settlement changes. The site of Zawyet al-Sultan in Middle Egypt was apparently abandoned and partly burned around the time of the Arab conquest. Analysis of surface remains at this site confirmed the difficulty of accurately dating this event on the basis of current information. Chapters3 and 4 analysethe effect of two mechanismsof Arab colonisation on Egyptian towns. First, an investigation of the occupationby soldiers of threatened frontier towns (ribats) is based on the site of Tinnis. Examination of the archaeological remains indicates a significant expansion of Tinnis in the eighth and ninth centuries, which is confirmed by references in the historical sources to building programmes funded by the central government. Second, the practice of murtaba ` al- jund, the seasonal exploitation of the town and its hinterland for the grazing of animals by specific tribal groups is examined with reference to Kharibta in the western Delta.