Legal Statement for Personal Use Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Rapport Baseline Rano Hp

DRAFT RAPPORT BASELINE RANO HP FEVRIER – MARS 2010 Table des matières Résumé exécutif ......................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction 16 Section 1 : Justification, objectifs et méthodologie de l’étude de base ................................... 18 1.1. Justification et objectifs de l’étude de base .................................................................... 18 1.2. Méthodologie de l’étude de base .................................................................................... 19 1.2.1 Type et méthodes d’enquête ...................................................................... 19 1.2.2 Echantillonnage ........................................................................................ 20 1.2.3 Sélection et formation des enquêteurs ....................................................... 25 1.2.4 Organisation de la collecte ....................................................................... 25 1.2.5 Exploitation et analyse des données.......................................................... 26 2.1 Cadre des résultats du Programme ................................................................................. 28 2.2 Cadre de performance du Programme............................................................................ 30 4.1 Cadre administratif du Programme ................................................................................ 34 3.1.1 Taille et composition des ménages ........................................................... -

Measles Outbreak

P a g e | 1 Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Madagascar: Measles Outbreak DREF n°: MDRMG014 / PMG033 Glide n°: Date of issue: 28 March 2019 Expected timeframe: 3 months Operation start date: 28 March 2019 Expected end date: 28 June 2019 Category allocated to the of the disaster or crisis: Yellow IFRC Focal Point: Youcef Ait CHELLOUCHE, Head of Indian National Society focal point: Andoniaina Ocean Islands & Djibouti (IOID) CCST will be project manager Ratsimamanga – Secretary General and overall responsible for planning, implementation, monitoring, reporting and compliance. DREF budget allocated: CHF 89,297 Total number of people affected: 98,415 cases recorded Number of people to be assisted: 1,946,656 people1 in the 10 targeted districts - Direct targets: 524,868 children for immunization - Indirect targets: 1,421,788 for sensitization Host National Society presence of volunteers: Malagasy red Cross Society (MRCS) with 12,000 volunteers across the country. Some 1,030 volunteers 206 NDRT/BDRTs, 10 full-time staff will be mobilized through the DREF in the 10 districts Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), German Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, Luxembourg Red Cross, French Red Cross through the Indian Ocean Regional Intervention Platform (PIROI). Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Ministry of Health, WHO, UNICEF. A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster Measles, a highly contagious viral disease, remains a leading cause of death amongst young children around the world, despite the availability of an effective vaccine. -

Small Hydro Resource Mapping in Madagascar

Public Disclosure Authorized Small Hydro Resource Mapping in Madagascar INCEPTION REPORT [ENGLISH VERSION] August 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized This report was prepared by SHER Ingénieurs-Conseils s.a. in association with Mhylab, under contract to The World Bank. It is one of several outputs from the small hydro Renewable Energy Resource Mapping and Geospatial Planning [Project ID: P145350]. This activity is funded and supported by the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP), a multi-donor trust fund administered by The World Bank, under a global initiative on Renewable Energy Resource Mapping. Further details on the initiative can be obtained from the ESMAP website. This document is an interim output from the above-mentioned project. Users are strongly advised to exercise caution when utilizing the information and data contained, as this has not been subject to full peer review. The final, validated, peer reviewed output from this project will be a Madagascar Small Hydro Atlas, which will be published once the project is completed. Copyright © 2014 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK Washington DC 20433 Telephone: +1-202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the consultants listed, and not of World Bank staff. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work and accept no responsibility for any consequence of their use. -

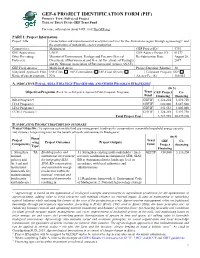

GEF-6 PROJECT IDENTIFICATION FORM (PIF) PROJECT TYPE: Full-Sized Project TYPE of TRUST FUND: GEF Trust Fund

GEF-6 PROJECT IDENTIFICATION FORM (PIF) PROJECT TYPE: Full-sized Project TYPE OF TRUST FUND: GEF Trust Fund For more information about GEF, visit TheGEF.org PART I: Project Information Project Title: Conservation and improvement of ecosystem services for the Atsinanana region through agroecology1 and the promotion of sustainable energy production Country(ies): Madagascar GEF Project ID:2 9793 GEF Agency(ies): UNEP GEF Agency Project ID: 01573 Other Executing Ministry of Environment, Ecology and Forestry (General Re-Submission Date: August 28, Partner(s): Directorate of Environment and General Directorate of Ecology) 2017 and the National Association of Environmental Action (ANAE) GEF Focal Area(s): Multi-focal Areas Project Duration (Months) 48 Integrated Approach Pilot IAP-Cities IAP-Commodities IAP-Food Security Corporate Program: SGP Name of parent program: N/A Agency Fee ($) 360,045 A. INDICATIVE FOCAL AREA STRATEGY FRAMEWORK AND OTHER PROGRAM STRATEGIES3 (in $) Objectives/Programs (Focal Areas, Integrated Approach Pilot, Corporate Programs) Trust GEF Project Co- Fund Financing financing BD-4 Program 9 GEFTF 1,324,201 5,193,750 LD-1 Program 1 GEFTF 800,000 5,687,500 LD-2 Program 3 GEFTF 341,553 4,000,000 CCM-1 Program 1 GEFTF 1,324,201 5,193,750 Total Project Cost 3,789,955 20,075,000 B. INDICATIVE PROJECT DESCRIPTION SUMMARY Project Objective: To optimise sustainable land use management, biodiversity conservation, renewable household energy security and climate change mitigation for the benefit of local communities in Madagascar (in $) Finan Project Trust -cing Project Outcomes Project Outputs GEF Co- Components Fund Type4 Project financing Financing 1. -

RAHARISOLONJANAHARY Rindraniaina Sylvie PROJET D

UNIVERSITE D’ANTANANARIVO DOMAINE SCIENCES ET TECHNOLOGIE MENTION SCIENCES DE LA TERRE ET DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT PARCOURS RESSOURCES MINERALES ET ENVIRONNEMENT Mémoire De fin d’étude pour l’obtention du Diplôme de Master 2 Parcours : Ressources Minérales et Environnement PROJET D’EXPLOITATION D’OR PAR DRAGUE SUCEUSE DANS LE LIT DE LA RIVIERE LOHARIANDAVA : CARACTERISATION DES PARAMETRES MINIERS, ENVIRONNEMENTAUX ET SOCIAUX Présentée par RAHARISOLONJANAHARY Rindraniaina Sylvie Soutenu le 5 Aout 2016 Devant les membres de jury Président du jury : Professeur RAKOTONDRAZAFY Raymond Rapporteur : Docteur RANDRIAMALALA René Paul Examinateurs : -Docteur RASOAMIARAMANANA Armand -Docteur RAMBOLAMANANA Voahangy UNIVERSITE D’ANTANANARIVO DOMAINE SCIENCES ET TECHNOLOGIE MENTION SCIENCES DE LA TERRE ET DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT PARCOURS RESSOURCES MINERALES ET ENVIRONNEMENT Mémoire De fin d’étude pour l’obtention du Diplôme de Master 2 Parcours : Ressources Minérales et Environnement PROJET D’EXPLOITATION D’OR PAR DRAGUE SUCEUSE DANS LE LIT DE LA RIVIERE LOHARIANDAVA : CARACTERISATION DES PARAMETRES MINIERS, ENVIRONNEMENTAUX ET SOCIAUX Présentée par RAHARISOLONJANAHARY Rindraniaina Sylvie Soutenu 5 Aout 2016 Devant les membres de jury Président du jury : Professeur RAKOTONDRAZAFY Raymond Rapporteur : Docteur RANDRIAMALALA René Paul Examinateurs : -Docteur RASOAMIARAMANANA Armand -Docteur RAMBOLAMANANA Voahangy DEDICACE A ma mère RAHARINELINA Nirinarisoa Jeannette. A la mémoire de mon père RAKOTONDRAZANANY, qui voudrait bien y assister, mais fut parti avant l’heure. Ceci marque que j’ai pu réaliser son rêve. A mes sœurs : Patricia, Hanitra et Hortense. A mes frères : José Alain et Setra. A mes beaux-frères : Roméo et Ndriana A mes neveux et nièces : Jordie, Tommy, Steven, Fanaiky, Miangaly, Mioty et Mirindra. A ma grand-mère : RAVAOARINELINA. -

MADAGASCAR (! ANALANJIROFO Anove Manompana! !

M A D A G A S C A R - N o r t h e r n A r e a fh General Logistics Planning Map International Primary Road \! National Capital International (!o Airport Boundary Secondary Road !! Major Town Domestic Airport Region Boundary o Antsisikala ! o Tertiary Road ! Intermediate Airstrip Town District Boundary Track/Trail h h ! ! ! Port Small Town Water Body Antsahampano ! ! ( River crossing Antsiranana ( ! ANTSIRANANA I ĥ Main bridge (ferry) Village River o Date Created: 07 March 2017 Prepared by: OSEP GIS Data Sources: UNGIWG, GeoNames, GAUL, LC, © OpenStreetMap Contributors Contact: [email protected] Map Reference: The boundaries and names and the designations used on this map do not ANTSIRANANA II Website: www.logcluster.org MDG_GLPM_North_A2P imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Anivorano Avaratra! ! Ambovonaomby ĥ Antsohimbondrona ! !h ! Antanambao ! Isesy Ampanakana ! o Ambilobe ! ! ĥ NOSY-BE Sangaloka Fasenina-Ampasy ĥ ! Beramanja ! Iharana o o (! ! ĥ !h !h! Hell-Ville Ampampamena o! ! VOHEMAR ĥ! Ambaliha AMBILOBE Fanambana ! Madirofolo ! Ambanja DIANA AMBANJA ! Masomamangy o Amboahangibe ! ! Bemanevika ! Ankasetra ĥ SAMBAVA ! Nosivolo h Sambava SAVA !o! o ! Doany ! Farahalana ! Marojala ( ( ĥ ! o Bealanana Analalava ! ! Ambatosia ! BEALANANA o Andapa ANDAPA ! Antsohihy ĥ ! Antsahanoro ! Manandriana ĥAntalaha !h ! o ! Andilambe !h Antsirabato ! Anjajavy o Matsoandakana ! ! Antsakabary ! ! o Anahidrano ! ! Marofinaritra Ambararata ANTSOHIHY BEFANDRIANA o NORD (Ambohitralanana ! ANALALAVA ! Befandriana ANTALAHA -

[ Manuel De Verification'i

~POBLIKAN'I MADAGASIKARA Tanindrazana - Fahafahanâ - Fahamarinana YIN1ST~RB DE L' ECONOMIE, DU PLAN ET DU REDRBSSBMENT SOCIAL DIRBCTION' GBNERALE DE LA BANQUE DES DON NEES DE L'BTAT COMMISSION N'ATIONALE DIRECTION DV RECENSEMBNT GENERAL- DU iECBNSENENT ~ENERAL DE LA POPULATION ET DE L'HABITAT DB LA 1'OPULATION ST J)E L'HABITAT ,. DEUXIEME RECENSEMENT GENERAL DE LA POPULATION ET DE L'HABITAT 1993 --- 1 / [ MANUEL DE VERIFICATION ' I Version 2.s . fO\<l.ocrsph\lIIanveT2.8 Janvier 94 REPOBLlKAN'I MADAGASlKARA 'farundrazalla - Fahafahana - Fahamarinana UINISTERE DE L'ECONOMIE, DU PLAN ET DU REDRESSEMENT SOCIAL DIRECTIO:-: GENERALE DE LA BANQUE DES DONNEES DE L'ETAT COMMISSION NATIONALE DIREC1ION Dl! RECENSEMENT GENERAL DU RECENSEMENT GENERAL DE LA POP U LATIO:i ET DE l' HABITAT DE LA POPULATION ET DE L'HABITAT DEUXIEME RECENSEMEl\rrr GEN]~RAL DE LA POPULATION Err DE L ~HA,BI'TAT 1993 MANUEL DE VERIFICATION 1 Il Version 2.s fb\docrBPh\manver2.s Janvier 94 SOI\.iMA1RE INTRODUCTIO~~ . 2 l - GENERALITES SUR LA VERIFICATION 1.1 - LA SECTION V"ERIFICATION ..•.........' , . ,........... 2 1.2 - LE TR~ VAIL DU \lt:RlFICATEUR ..................... 2 1.3 - L'IDEN1IFICATION DES QUESTIONNAIRES .. ,.... ~, ...... 3 1.4- LES QUESTIOl'.~.AIRES-SUITE ...................... 5 ,2 '- METIIODE DE'VERIFICATION o - MILIEU ..............................••........ 5 l - 'FARITA.N1" 2 - F IVONDRONA1\fPOK0l'41 Al"\""l , 3 - FIRAISM1POKONTMry· ..............•...•..........• 5 4 -. N°DE LA ZONE 5 - N e DU S EGME?\l . ~ . .. .... 6 6 "- FOKONTAl~l'· 7 - LOCALITE .... ' .....•..............•..... la ••' • • • • • • 8 8 - N ~ 'DU B.ATIMEr1T .•..-. _ .....•.. ~ ..••.•' .•••.•..•• · • 8 . 9 - TI'1>E' D'UTILISATION . '........................ · . 8 , <> DU ,..,.-c.... TAGE .. 9 ,~ 10. ~ _N Ir}...!::..l'" .• • . -

Madagascar Cyclone Enawo Sit

Madagascar: Cyclone Enawo Situation Report No. 4 28 March 2017 This report is issued by the Bureau National de Gestion des Risques et des Catastrophes (BNGRC) and the Humanitarian Country Team in Madagascar. It covers the period from 17 to 24 March. The next report will be issued early in April 2017, and will be published every two weeks thereafter. Highlights • On 23 March 2017, humanitarian partners in Madagascar and the Government jointly launched a Flash Appeal for $20 million to provide support to 250,000 vulnerable people affected by Cyclone Enawo. • Response activities are rapidly being scaled up, with supplies, additional humanitarian organizations and staff arriving in the most-affected areas of north- eastern Madagascar. • Since the start of the response, more than 76,400 people have received food assistance, and more than 55,700 people have received WASH support. In addition, 60,000 people have received support to access health care, while 8,050 households have benefited from emergency shelter assistance. The Education Cluster has also provided emergency educational needs of 45,100 children. • An elevated rate of malaria cases has been reported from Antalaha and Brickaville in comparison to March 2016; however, no increase in cases of diarrhoea has been reported to date. • UNDAC mission has concluded on 24 March and the work has been handed over to national and in- The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do country counterparts. not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. 434,000 5,300 40,520 3,900 >1,300 105 Affected people Currently displaced Houses destroyed Classrooms Polluted water Damaged health damaged* points centres Situation Overview On 23 March 2017, the United Nations, together with other humanitarian partners and the Government of Madagascar launched the Madagascar Cyclone Enawo Flash Appeal, requesting just over US$ 20 million to assist 250,000 most vulnerable people affected by the cyclone for the next three months (until 23 June). -

Madagascar: the Farmer's Perspective

FEBRUARY 1993 WORKING PAPER 34 Constraints on Rice Production in Madagascar: The Farmer's Perspective Ren6 Bernier and Paul A. Dorosh CR CORNELL FOOD AND NUTRITION POLICY PROGRAM. CONSTRAINTS ON RICE PRODUCTION IN MADAGASCAR: THE FARMER'S PERSPECTIVE Ren6 Bernier and Paul Dorosh The Cornell Food and Nutrition Policy Program (CFNPP) was created in 1988 within the Division of Nutritional Sciences, College of Human Ecology, Cornell University, to undertake research, training, and technical assistance infood and nutrition policy with emphasis on developing countries. CFNPP is served by an advisory committee of faculty from the Division of Nutritional Sciences, College of Human Ecology; the Departments of Agricultural Economics, Nutrition, City and Regional Planning, Rural Sociology; and from the Cornell Institute for International Foud, Agriculture and Development. Graduate students and faculty from these units sometimes collaborate with CFNPP on specific projects. The CFNPP professional staff includes nutritionists, economists, and anthropologists. CFNPP is funded by several donors including the Agency for International DEvelopment, the World Bank, UNICEF, the Pew Memorial Trust, the Rockefeller and For-d Foundations, The Carnegie Corperation, The Thrasher Research Fund, and individual country governments. Preparation of this document was financed by the U.S. Agency for International Development under USAID Cooperative Agreement AFR-000-A-0-804F-O0. © 1993 Cornell Food and Nutrition Polic,'. Program ISBN 1-56401-134-8 This Working Paper series provides a vehicle for rapid and informal reporting of results from CFNPP research. Some of the findings may be prelimirnary and subject to further analysis. This document was word processed by Mary Beth Getsey. The manuscript was edited by Elizabeth Mercado. -

World Bank Document

Ministry of Transportation and Meteorology World Bank Ministry of Public Works E524 Volume 1 Public Disclosure Authorized Rural Transportation Project Environmental and Social Public Disclosure Authorized Impact Assessment Public Disclosure Authorized December 2001 Prepared by Transport Sector Project (TSP) NGO Lalana Basler & Hofmann Based on the preliminary designs of the following consulting firms: Public Disclosure Authorized DINIKA (Tananarive) MICS - ECR - AEC - SECAM (Fianarantsoa) ESPACE - MAHERY (Taomasina) EC PLUS - JR SAINA (Mahajanga) 4 A OSIBP - SOMEAH (Toliary) F CO PY EIIRA - ANDRIAMBOLA - BIC (Antsiranana) Projet de Transport Rural, Madagascar - Evaluation des impacts environnementaux et sociaux Table of Contents 1 Summary of Environmental and Social Assessment .................................................. 1 1.1 Proposed Project ........................................ 1 1.2 Transport Sector Environmental Assessment ...................................... 1 1.3 Environmental Assessment for APL 2 ...................................... 1 1.4 Policy and Legislative Framework ....................................... 1 1.5 Methodology ...................................... 2 1.6 Participatory approach ...................................... 2 1.7 Rural transport rehabilitation component ....................................... 3 1.8 Potential environmental impacts ...................................... 3 1.9 Resettlement and cultural heritage ....................................... 4 1.10 Rail and port infrastructure rehabilitation -

Projet D'elaboration Du Schéma Directeur Pour Le Développement

Ministère de l’Aménagement du Territoire, de l'Habitat et des Travaux Publics (MAHTP) Gouvernement de la République de Madagascar Projet d’Elaboration du Schéma Directeur pour le Développement de l’Axe Economique TaToM (Antananarivo-Toamasina, Madagasikara) Rapport Final Résumé Octobre 2019 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale (JICA) Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. CTI Engineering Co., Ltd. EI JR 19-103 Ministère de l’Aménagement du Territoire, de l'Habitat et des Travaux Publics (MAHTP) Gouvernement de la République de Madagascar Projet d’Elaboration du Schéma Directeur pour le Développement de l’Axe Economique TaToM (Antananarivo-Toamasina, Madagasikara) Rapport Final Résumé Octobre 2019 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale (JICA) Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. CTI Engineering Co., Ltd. Taux de change EUR 1.00 = JPY 127.145 EUR 1.00 = MGA 3,989.95 USD 1.00 = JPY 111.126 USD 1.00 = MGA 3,489.153 MGA 1.00 = JPY 0.0319 Moyennes pendant la période comprise entre Juin 2018 et Juin 2019 Divisions administratives de Madagascar Les divisions administratives décentralisées de Madagascar sont formées de 22 régions, qui sont subdivisées en 114 districts. Les districts se divisent en communes et chaque commune en fokontany. Outre les divisions administratives décentralisées, le pays est subdivisé en six provinces, divisées en 24 préfectures. Les préfectures sont divisées en 117 districts, qui sont subdivisés en arrondissements. La délimitation des régions et des préfectures est la même sauf pour deux préfectures, Nosy Be et Sainte Marie, qui font exception. La délimitation de ces deux préfectures suit celle du district. -

Madagascar Cyclone Enawo

Andilamena Soanierana Ivongo MA002_4 ! Vatomora I Antseranamatso Amboditolongo ! Ampasimbe ! ! Ambahoabe Ambodiampana Soanierana Andapafito Ivongo Ambatobe ! Befotaka ! Andapafito Fotsialanana Bevovo!nana ! Ambodinanto Andilamena ! Ampasimbola ! ! Sahafiana II ! Ambodirafia Antsiatsiaka ! S ° 7 Soanierana 1 Ivongo Ambodihazinina ! Andranomiditra ! Ambodimanga Antsiatsiaka ! ! Ambolozatsy Tananambao ! ! Manakambahiny Ambodirotra Vohimafaitra ! Manakantafana ! ! ! ! Ambatosondrona Andongozabe Ampasimbola ! Anjahama!rina ! ! Marovovonana AMPASIMBE Ambohitsara Antsara I ! ! ! Am!pasimbe Antsiradava !Ambanja ! Antenina Manantsa! trana ! Anjahambe Saranambana Ambatoharanana Tanetilava I Ambodiampaly ! III ! ! Marokiso Ambodibonara ! Miorimivalana Vohipeno ! Anamborano ! Ambodihara Ambinanisahonotra ! ! Marovato I ! Ampangamena Ambarimbalava Savontsira Vohipeno Andrebakely ! ! ! ! Ambinanindranomena ! ! Anjahamarina Nord Ampasimbola Fenerive ! Ambodihasina I ! Mahatera ! Est Marotrano Vohimena Andapabe ! Tanambao I Antsiradava ! ! ! Takobola !Ampasina ! Miorimivalana Ambatomitrozona ! A!MPASINA MANINGORY ! Maningory Ambilodozera ! Soberaka ! Anorombato ! Amboditononana Ambodinanto ! ! ! Ambodimanga II Ambodivohitra Rantolava ! Vohipenohely ! ! Saharina Tanambao II Beolaka Ambodihazinina ! Saranambana ! ! ! Tanambao Ankorabe ! Tampolo Vohilengo ! ! Andapa II Mangoandrano Ambatoha!ranana ! Andasibe Sakana Vohilengo ! ! Anarivo ! Marojomana ! Tanambiavy ! ! Mah!avanona Ambatoharanana ! Savontsira Ambatoharanana Antetezampafana ! Tsaratampona I !