The Ordeal of Cpasstnore Williamson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Early Abolitionists of Lancaster County

The Early Abolitionists of Lancaster County, In giving a history of the Abolition movement in Lancaster county,or else- where, the question seems first to arise, what is specially meant by the term "Abolitionist." The indiscrimin- ate manner in which it was used sixty years ago against every person who in any manner sympathized with the anti- slavery movement leaves me some- what in doubt as to what phase of the subject I am supposed to treat, In fact, I am reminded very much of a speech I heard made by Thaddeus Ste- vens when yet a small boy. It was in the Congressional campaign of 1858, when Mr. Stevens was a candidate for Congress from this district. The per- oration of his speech was substantially as follows. I quote from memory: "But in answer to all this I hear one reply, namely, Stevens is an Abolition- ist. The indiscriminate manner with which the term is used, I am frank to confess, leaves me somewhat in doubt as to what is meant by it. But the venom and spleen with which it is hurled at some of us would indicate, at least, that it is a term of reproach and used only against monsters and outlaws of society. If it is meant by an Abolitionist that I am one of those terrible, heinous-looking animals with cloven hoofs and horns, such as is de- scribed in. legend and fiction, and in Milton's "Paradise Lost," I am not very handsome, to be sure, but I don't think I am one of those. -

WILLIAM STILL and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Author(S): Larry Gara Source: Pennsylvania History, Vol

WILLIAM STILL AND THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Author(s): Larry Gara Source: Pennsylvania History, Vol. 28, No. 1 (January, 1961), pp. 33-44 Published by: Penn State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27770004 . Accessed: 09/01/2015 08:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Pennsylvania History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 64.9.56.53 on Fri, 9 Jan 2015 08:30:11 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions WILLIAM STILL AND THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD By Larry Gar a* writer of a popular account of the underground railroad THE in Pennsylvania stated in his preface that "it required the a manhood of man and the unflinching fortitude of a woman, ... to be an abolitionist in those days, and especially an Under was ground Railroad agent/'1 He referring to the noble minority who stood firm when the abolitionists were being "reviled and in persecuted" both the North and the South. Other underground railroad books?some of them written by elderly abolitionists? on put similar emphasis the heroic conductors of the mysterious organization. -

Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr

Copyright © 2013 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation i Table of Contents Letter from Erin Carlson Mast, Executive Director, President Lincoln’s Cottage Letter from Martin R. Castro, Chairman of The United States Commission on Civil Rights About President Lincoln’s Cottage, The National Trust for Historic Preservation, and The United States Commission on Civil Rights Author Biographies Acknowledgements 1. A Good Sleep or a Bad Nightmare: Tossing and Turning Over the Memory of Emancipation Dr. David Blight……….…………………………………………………………….….1 2. Abraham Lincoln: Reluctant Emancipator? Dr. Michael Burlingame……………………………………………………………….…9 3. The Lessons of Emancipation in the Fight Against Modern Slavery Ambassador Luis CdeBaca………………………………….…………………………...15 4. Views of Emancipation through the Eyes of the Enslaved Dr. Spencer Crew…………………………………………….………………………..19 5. Lincoln’s “Paramount Object” Dr. Joseph R. Fornieri……………………….…………………..……………………..25 6. Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr. Allen Carl Guelzo……………..……………………………….…………………..31 7. Emancipation and its Complex Legacy as the Work of Many Hands Dr. Chandra Manning…………………………………………………..……………...41 8. The Emancipation Proclamation at 150 Dr. Edna Greene Medford………………………………….……….…….……………48 9. Lincoln, Emancipation, and the New Birth of Freedom: On Remaining a Constitutional People Dr. Lucas E. Morel…………………………….…………………….……….………..53 10. Emancipation Moments Dr. Matthew Pinsker………………….……………………………….………….……59 11. “Knock[ing] the Bottom Out of Slavery” and Desegregation: -

Bury Me Not in a Land of Slaves

Bury Me Not in a Land of Slaves T ough her cheek was pale and anxious, Yet, with look and brow sublime, By the pale and trembling Future Stood the Crisis of our time. And f om many a throbbing bosom Came the words in fear and gloom, A short history of Immediatist Tell us, Oh! thou coming Crisis, What shall be our country’s doom? Abolitionism in Philadelphia, Shall the wings of dark destruction Brood and hover o’er our land, 1830s-1860s Till we trace the steps of ruin By their blight, f om strand to strand? “Lines,” by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper fragments distro by Arturo Castillon tucson, az 2019 alism and Southern slavery, impossible to maintain. In this, the Civil War con- f rmed the basic lesson of every revolution, which stands the logic of gradualism on its head. Revolution doesn’t develop in a gradual, incremental way, with leg- islative preconditions, but instead with strategic, uncompromising actions that over time heighten the structural contradictions of the system. T e will for revolution can only be satisf ed in this way—with consistent, stra- tegic, revolutionary activity. Yet the masses of people can only acquire and strengthen the will for revolution in the course of the day-to-day struggle against the existing order—in other words, within the limits of the existing sys- Publishing this text at a time of intensifying struggle against prisons and border tem. T us, we run into a contradiction. On the one hand, we have the masses of enforcement feels appropriate. -

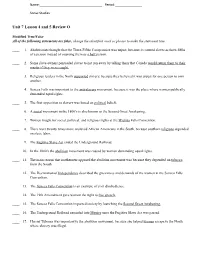

Unit 7 Lesson 4 and 5 Review O

Name:___________________________________ Period:_______________ Social Studies Unit 7 Lesson 4 and 5 Review O Modified True/False All of the following statements are false, change the identified word or phrase to make the statement true. ____ 1. Abolitionists thought that the Three-Fifths Compromise was unjust, because it counted slaves as three-fifths of a person instead of counting them as a half p erson. ____ 2. Some slave owners persuaded slaves to not run away by telling them that Canada w ould return them to their master if they were caught. ____ 3. Religious leaders in the North supported slavery, because they believed it was unjust for one person to own another. ____ 4. Seneca Falls was important to the a nti-slavery movement, because it was the place where women publically demanded equal rights. ____ 5. The first opposition to slavery was based on political beliefs. ____ 6. A social movement in the 1800’s is also known as the Second Great Awakening. ____ 7. Women fought for social, political, and religious rights at the Wichita Falls Convention. ____ 8. There were twenty times more enslaved African Americans in the South, because southern religions depended on slave labor. ____ 9. The Fugitive Slave Act ended the Underground Railroad. ____ 10. In the 1800’s the abolition movement was caused by women demanding equal rights. ____ 11. The main reason that northerners opposed the abolition movement was because they depended on t obacco from the South. ____ 12. The Declaration of I ndependence described the grievances and demands of the women at the Seneca Falls Convention. -

GAZETTE a Quarterly Newsletter to the Citizens of Westtown Township - Spring Issue #25

WESTTOWN GAZETTE A Quarterly Newsletter to the Citizens of Westtown Township - Spring Issue #25 In like a lion... ...out like a lamb. GREETINGS WESTTOWN FRIENDS & NEIGHBORS, AND HAPPY SPRING! Soon after the spring daffodils and The most significant deficiency with My final words are about spring crocuses bloom, the township will the existing garage is size. It has three cleaning. Westtown is a wonderful break ground on a new Public Works vehicle bays, but they are not wide community where residents take great facility at the intersection of E. Pleasant or deep enough to accommodate a pride in keeping their property and Grove Road and Wilmington Pike. The loaded 40’ X 11’ truck with snowplow. neighborhoods clean. Nevertheless, Public Works Department consists During a snow storm, repairs must every spring we receive comments of six highly skilled employees who be made outside in extremely harsh and complaints about trash that has are responsible for operating and conditions. The new garage will have accumulated over the winter along maintaining Westtown’s sewage four 70‘ X 14‘ bays, so trucks can the sides of township and state roads. treatment facilities, roads, bridges, be brought inside a heated space Please accept this as a respectful plea stormwater management facilities, to thaw and be worked on quickly to pick up roadside trash, particularly municipal buildings, parks and open and safely, and also stored securely. on properties that front major roads space. The department is managed Offices, locker rooms, break room, (Street Road, S. Chester Road, Wilmington Pike, West Chester Pike, by director, Mark Gross, who has and a separate wash bay for steam Oakbourne Road, Westtown Road, and worked for the township since 2000. -

Next Stop: Liberty

The Wall Street Journal January 17-18, 2015 Book Review “Gateway to Freedom” by Eric Foner, Norton, $26.95, 301 pages. Next Stop: Liberty New York City’s abolitionist operatives showed cunning and courage as they worked to help fugitive slaves. by David S. Reynolds In March 1849, Henry Brown, an enslaved tobacco worker in Richmond, Va., escaped to the North in dramatic fashion. Aided by a white friend, he was put inside a small crate that was shipped to Philadelphia. During the 24-hour journey, he twice almost died when he was turned upside-down. He was received in Philadelphia by the abolitionist James Miller McKim, who tapped on the container and asked, “All right?” Brown answered, “All right, sir.” When the crate was finally opened, Brown emerged, beaming, and launched into a “hymn of praise.” He was sent to New York City and then New Bedford, Mass. Soon famous as Henry “Box” Brown, he went to England, where he became a fixture on the abolitionist lecture circuit. Brown’s escape is one of many gripping tales told in Eric Foner ’s excellent “Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden Story of the Underground Railroad.” Mr. Foner’s book joins a number of previous studies—from William Still’s “The Underground Railroad” (1872) through Larry Gara ’s “The Liberty Line” (1961) to Fergus M. Bordewich ’s “Bound for Canaan” (2005)—that have taken on the challenge of resurrecting the Americans who assisted runaway slaves in their journeys to freedom. The challenge is daunting. The Underground Railroad, as its metaphorical name suggests, was a clandestine, illegal network. -

Underground Railroad Sites

HISTORICAL MARKERS LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES & TOURS Although time has taken its toll on many 18 Historical Society of Pennsylvania Underground Railroad landmarks, these historical 1300 Locust Street, hsp.org Tuesday, 12:30–5:30 p.m.; Wednesday, 12:30–8:30 p.m.; markers recount the people, places and events that Thursday, 12:30–5:30 p.m.; Friday, 10 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. paved the way to freedom for those who dared and, Hundreds of documents relating to the abolitionist movement are part of ultimately, helped end the practice of slavery. this repository of 600,000 printed items and more than 21 million manuscripts and graphic items. Visitors can view Underground Railroad agent William Still’s journal that documents the experiences of enslaved people who passed through Philadelphia. 6 Pennsylvania Hall 14 Robert Mara Adger 19 Library Company of Philadelphia 6th Street near Race Street 823 South Street 1314 Locust Street, librarycompany.org First U.S. building specifically African American businessman and Weekdays, 9 a.m. – 4:45 p.m. constructed as an abolitionist meeting co-founder and president of the Among this Benjamin Franklin–established organization’s holdings is the space (1838); ransacked and burned American Negro Historical Society. 13,000-piece Afro-American Collection, which includes documents and four days after opening. books about slavery and abolitionism, Frederick Douglass’ narratives, 15 William Whipper JOHNSON HOUSE portraits of African American leaders and other artifacts. 7 Philadelphia Female 919 Lombard Street Anti-Slavery Society African American businessman * Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple University 5th & Arch streets who was active in the Underground (3 miles from Historic District) Circa 1833 group of indomitable Railroad and co-founder of the Sullivan Hall, 1330 W. -

THE POLITICS of SLAVERY and FREEDOM in PHILADELPHIA, 1820-1847 a Dissertation Submitted To

NEITHER NORTHERN NOR SOUTHERN: THE POLITICS OF SLAVERY AND FREEDOM IN PHILADELPHIA, 1820-1847 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Elliott Drago May, 2017 Examining Committee Members: Andrew Isenberg, Chair, Temple University, History Harvey Neptune, Temple University, History Jessica Roney, Temple University, History Jonathan Wells, University of Michigan, History Judith Giesberg, Villanova University, History Randall Miller, External Member, Saint Joseph’s University, History © Copyright 2017 by Elliott Drago All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the conflict over slavery and freedom in Philadelphia from 1820 to 1847. As the northernmost southern city in a state that bordered three slave states, Philadelphia maintained a long tradition of abolitionism and fugitive slave activity. Conflicts that arose over fugitive slaves and the kidnapping of free African-Americans forced Philadelphians to confront the politics of slavery. This dissertation argues that until 1847, Pennsylvania was in effect a slave state. The work of proslavery groups, namely slave masters, their agents, white and black kidnappers, and local, state, and national political supporters, undermined the ostensible successes of state laws designed to protect the freedom of African-Americans in Pennsylvania. Commonly referred to as “liberty laws,” this legislation exposed the inherent difficulty in determining the free or enslaved status of not only fugitive slaves but also African-American kidnapping victims. By studying the specific fugitive or kidnapping cases that inspired these liberty laws, one finds that time and again African-Americans and their allies forced white politicians to grapple with the reality that Pennsylvania was not a safe-haven for African-Americans, regardless of their condition of bondage or freedom. -

Bondwoman' S Narrative Pdf

Bondwoman' s narrative pdf Continue The Bondwoman's Narrative First editionEditorHenry Louis Gates, Jr. AuthorHannah CraftsCover artist Giorgetta B. McReeCountryUnited StatesLanguageGelstaalPublisherWarner BooksPublication date2002Media typePrint (Paperback and Hardback)Pages365ISBN0-446-69029 -5 (Paper isbn 0-446-53008-5 (Hardback)OCLC520828664 The Bondwoman's Narrative is a novel by Hannah Crafts, a self-proclaimed slave who escaped from North Carolina. She probably wrote the novel in the mid-19th century. However, the manuscript was only verified and correctly published in 2002. Some scholars believe that the novel, written by an African-American woman and former slave, was written between 1853 and 1861. It is one of the few books of a fugitive slave, others are the novel Our Nig by Harriet Wilson, published in 1859, and the autobiography Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs, published in 1861. [1] The 2002 publication includes a foreword by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., professor of African-American literature and history at Harvard University, describing his buying of the manuscript, verifying it, and research to identify the author. [1] Crafts was believed to be a pseudonym of an enslaved woman who had escaped from the John Hill Wheeler plantation. In September 2013, Gregg Hecimovich, an English professor at Winthrop University, documented the writer as Hannah Bond, an African-American slave who escaped from Wheeler's plantation in Murfreesboro, North Carolina, around 1857. She reached the North and settled in New Jersey. [2] Plot summary Title page of manuscript of The Bondwoman's Narrative. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, gift from Henry Louis Gates Jr. -

Death and Madness in the Bondwoman's Narrative Natalie L

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2008 A sentimental tale: death and madness in The Bondwoman's Narrative Natalie L. Meyer Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Natalie L., "A sentimental tale: death and madness in The Bondwoman's Narrative" (2008). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15302. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15302 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A sentimental tale: death and madness in The Bondwoman’s Narrative by Natalie L. Meyer A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Program of Study Committee: Constance J. Post, Major Professor Jane Davis Amy Slagell Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2008 UMI Number: 1453118 UMI Microform 1453118 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. HENRY LOUIS GATES JR.’S THE DISCOVERY OF HANNAH CRAFTS 3 III. -

The Deliverance of Henry “Box” Brown and Antebellum Postal Politics

Fugitive Mail 5 Fugitive Mail: The Deliverance of Henry “Box” Brown and Antebellum Postal Politics Hollis Robbins On March 29, 1849, in Richmond, Virginia, a thirty-four-year old, 200-pound slave named Henry Brown asked two friends to pack him in a wooden box and ship it by express mail to Philadelphia. They did and he arrived alive twenty- seven hours later with a new name and a marketable story. The Narrative of the Life of Henry “Box” Brown, published months later (with the help of ghostwriter Charles Stearns), made Brown quickly famous.1 Brown toured America and England describing his escape and jumping out of his famous box. In 1850, Brown and partner James C.A. Smith added to the show a moving panorama, “The Mirror of Slavery,” depicting the horrors of slavery and the slave trade. Audiences dwindled, however, and after a dispute over money in 1851, Brown parted ways with Smith and with most of his supporters. By 1855, Brown was largely forgotten. In the last dozen years, Henry “Box” Brown’s Narrative has re-emerged to enjoy a kind of academic second act in African American Studies. Recent books and articles by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Richard Newman, John Ernest, Jeffrey Ruggles, Daphne Brooks, Marcus Wood, and Cynthia Griffin Wolff celebrate the rich symbolism of deliverance in Brown’s story.2 As Gates writes in his forward to a recent edition of Brown’s Narrative, the appeal of the tale stems, in part, from the fact that Brown made literal much that was implicit in the symbolism of enslavement.