Rescue of Jane Johnson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WILLIAM STILL and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Author(S): Larry Gara Source: Pennsylvania History, Vol

WILLIAM STILL AND THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Author(s): Larry Gara Source: Pennsylvania History, Vol. 28, No. 1 (January, 1961), pp. 33-44 Published by: Penn State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27770004 . Accessed: 09/01/2015 08:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Pennsylvania History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 64.9.56.53 on Fri, 9 Jan 2015 08:30:11 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions WILLIAM STILL AND THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD By Larry Gar a* writer of a popular account of the underground railroad THE in Pennsylvania stated in his preface that "it required the a manhood of man and the unflinching fortitude of a woman, ... to be an abolitionist in those days, and especially an Under was ground Railroad agent/'1 He referring to the noble minority who stood firm when the abolitionists were being "reviled and in persecuted" both the North and the South. Other underground railroad books?some of them written by elderly abolitionists? on put similar emphasis the heroic conductors of the mysterious organization. -

Bury Me Not in a Land of Slaves

Bury Me Not in a Land of Slaves T ough her cheek was pale and anxious, Yet, with look and brow sublime, By the pale and trembling Future Stood the Crisis of our time. And f om many a throbbing bosom Came the words in fear and gloom, A short history of Immediatist Tell us, Oh! thou coming Crisis, What shall be our country’s doom? Abolitionism in Philadelphia, Shall the wings of dark destruction Brood and hover o’er our land, 1830s-1860s Till we trace the steps of ruin By their blight, f om strand to strand? “Lines,” by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper fragments distro by Arturo Castillon tucson, az 2019 alism and Southern slavery, impossible to maintain. In this, the Civil War con- f rmed the basic lesson of every revolution, which stands the logic of gradualism on its head. Revolution doesn’t develop in a gradual, incremental way, with leg- islative preconditions, but instead with strategic, uncompromising actions that over time heighten the structural contradictions of the system. T e will for revolution can only be satisf ed in this way—with consistent, stra- tegic, revolutionary activity. Yet the masses of people can only acquire and strengthen the will for revolution in the course of the day-to-day struggle against the existing order—in other words, within the limits of the existing sys- Publishing this text at a time of intensifying struggle against prisons and border tem. T us, we run into a contradiction. On the one hand, we have the masses of enforcement feels appropriate. -

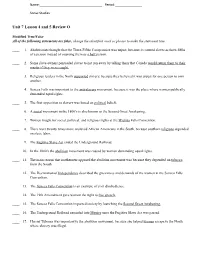

Unit 7 Lesson 4 and 5 Review O

Name:___________________________________ Period:_______________ Social Studies Unit 7 Lesson 4 and 5 Review O Modified True/False All of the following statements are false, change the identified word or phrase to make the statement true. ____ 1. Abolitionists thought that the Three-Fifths Compromise was unjust, because it counted slaves as three-fifths of a person instead of counting them as a half p erson. ____ 2. Some slave owners persuaded slaves to not run away by telling them that Canada w ould return them to their master if they were caught. ____ 3. Religious leaders in the North supported slavery, because they believed it was unjust for one person to own another. ____ 4. Seneca Falls was important to the a nti-slavery movement, because it was the place where women publically demanded equal rights. ____ 5. The first opposition to slavery was based on political beliefs. ____ 6. A social movement in the 1800’s is also known as the Second Great Awakening. ____ 7. Women fought for social, political, and religious rights at the Wichita Falls Convention. ____ 8. There were twenty times more enslaved African Americans in the South, because southern religions depended on slave labor. ____ 9. The Fugitive Slave Act ended the Underground Railroad. ____ 10. In the 1800’s the abolition movement was caused by women demanding equal rights. ____ 11. The main reason that northerners opposed the abolition movement was because they depended on t obacco from the South. ____ 12. The Declaration of I ndependence described the grievances and demands of the women at the Seneca Falls Convention. -

GAZETTE a Quarterly Newsletter to the Citizens of Westtown Township - Spring Issue #25

WESTTOWN GAZETTE A Quarterly Newsletter to the Citizens of Westtown Township - Spring Issue #25 In like a lion... ...out like a lamb. GREETINGS WESTTOWN FRIENDS & NEIGHBORS, AND HAPPY SPRING! Soon after the spring daffodils and The most significant deficiency with My final words are about spring crocuses bloom, the township will the existing garage is size. It has three cleaning. Westtown is a wonderful break ground on a new Public Works vehicle bays, but they are not wide community where residents take great facility at the intersection of E. Pleasant or deep enough to accommodate a pride in keeping their property and Grove Road and Wilmington Pike. The loaded 40’ X 11’ truck with snowplow. neighborhoods clean. Nevertheless, Public Works Department consists During a snow storm, repairs must every spring we receive comments of six highly skilled employees who be made outside in extremely harsh and complaints about trash that has are responsible for operating and conditions. The new garage will have accumulated over the winter along maintaining Westtown’s sewage four 70‘ X 14‘ bays, so trucks can the sides of township and state roads. treatment facilities, roads, bridges, be brought inside a heated space Please accept this as a respectful plea stormwater management facilities, to thaw and be worked on quickly to pick up roadside trash, particularly municipal buildings, parks and open and safely, and also stored securely. on properties that front major roads space. The department is managed Offices, locker rooms, break room, (Street Road, S. Chester Road, Wilmington Pike, West Chester Pike, by director, Mark Gross, who has and a separate wash bay for steam Oakbourne Road, Westtown Road, and worked for the township since 2000. -

Underground Railroad Sites

HISTORICAL MARKERS LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES & TOURS Although time has taken its toll on many 18 Historical Society of Pennsylvania Underground Railroad landmarks, these historical 1300 Locust Street, hsp.org Tuesday, 12:30–5:30 p.m.; Wednesday, 12:30–8:30 p.m.; markers recount the people, places and events that Thursday, 12:30–5:30 p.m.; Friday, 10 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. paved the way to freedom for those who dared and, Hundreds of documents relating to the abolitionist movement are part of ultimately, helped end the practice of slavery. this repository of 600,000 printed items and more than 21 million manuscripts and graphic items. Visitors can view Underground Railroad agent William Still’s journal that documents the experiences of enslaved people who passed through Philadelphia. 6 Pennsylvania Hall 14 Robert Mara Adger 19 Library Company of Philadelphia 6th Street near Race Street 823 South Street 1314 Locust Street, librarycompany.org First U.S. building specifically African American businessman and Weekdays, 9 a.m. – 4:45 p.m. constructed as an abolitionist meeting co-founder and president of the Among this Benjamin Franklin–established organization’s holdings is the space (1838); ransacked and burned American Negro Historical Society. 13,000-piece Afro-American Collection, which includes documents and four days after opening. books about slavery and abolitionism, Frederick Douglass’ narratives, 15 William Whipper JOHNSON HOUSE portraits of African American leaders and other artifacts. 7 Philadelphia Female 919 Lombard Street Anti-Slavery Society African American businessman * Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple University 5th & Arch streets who was active in the Underground (3 miles from Historic District) Circa 1833 group of indomitable Railroad and co-founder of the Sullivan Hall, 1330 W. -

Bondwoman' S Narrative Pdf

Bondwoman' s narrative pdf Continue The Bondwoman's Narrative First editionEditorHenry Louis Gates, Jr. AuthorHannah CraftsCover artist Giorgetta B. McReeCountryUnited StatesLanguageGelstaalPublisherWarner BooksPublication date2002Media typePrint (Paperback and Hardback)Pages365ISBN0-446-69029 -5 (Paper isbn 0-446-53008-5 (Hardback)OCLC520828664 The Bondwoman's Narrative is a novel by Hannah Crafts, a self-proclaimed slave who escaped from North Carolina. She probably wrote the novel in the mid-19th century. However, the manuscript was only verified and correctly published in 2002. Some scholars believe that the novel, written by an African-American woman and former slave, was written between 1853 and 1861. It is one of the few books of a fugitive slave, others are the novel Our Nig by Harriet Wilson, published in 1859, and the autobiography Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs, published in 1861. [1] The 2002 publication includes a foreword by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., professor of African-American literature and history at Harvard University, describing his buying of the manuscript, verifying it, and research to identify the author. [1] Crafts was believed to be a pseudonym of an enslaved woman who had escaped from the John Hill Wheeler plantation. In September 2013, Gregg Hecimovich, an English professor at Winthrop University, documented the writer as Hannah Bond, an African-American slave who escaped from Wheeler's plantation in Murfreesboro, North Carolina, around 1857. She reached the North and settled in New Jersey. [2] Plot summary Title page of manuscript of The Bondwoman's Narrative. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, gift from Henry Louis Gates Jr. -

Death and Madness in the Bondwoman's Narrative Natalie L

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2008 A sentimental tale: death and madness in The Bondwoman's Narrative Natalie L. Meyer Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Natalie L., "A sentimental tale: death and madness in The Bondwoman's Narrative" (2008). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15302. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15302 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A sentimental tale: death and madness in The Bondwoman’s Narrative by Natalie L. Meyer A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Program of Study Committee: Constance J. Post, Major Professor Jane Davis Amy Slagell Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2008 UMI Number: 1453118 UMI Microform 1453118 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. HENRY LOUIS GATES JR.’S THE DISCOVERY OF HANNAH CRAFTS 3 III. -

The Ordeal of Cpasstnore Williamson

^Antislavery ^hCartyrdom: The Ordeal of cPasstnore Williamson N JULY 18, 1855, John H. Wheeler, United States Minister to Nicaragua, was traveling through Philadelphia en route O to New York City, where he would embark on a voyage to resume his duties in that Central American country. Accompanying Wheeler were three Virginia slaves whom he had purchased two years earlier, Jane Johnson and her sons, Daniel and Isaiah. Well aware of the antislavery sentiment existing in Philadelphia, Wheeler maintained close surveillance of his slaves, twice warning Jane that she was to talk to no one. After visiting a relative in the city, Wheeler and his party proceeded to Bloodgood's Hotel, near the Walnut Street wharf on the Delaware River. During the two-and-a-half hour wait at the hotel, Jane, disregarding her owner's orders, twice informed passing Negroes that she was a slave and desirous of her freedom. She accomplished these acts while Wheeler was eating dinner. Immediately after completing his meal, Wheeler rejoined his slaves and they then boarded the Washington, a boat upon which they were scheduled to sail at 5 :oo P.M.1 Despite Wheeler's probable expectation that once aboard his wait for departure would be a short and uneventful one, events of quite a different nature transpired. After learning of the Wheeler slaves' situation, Passmore Williamson and other Philadelphians hurried to the Washington and liberated Jane Johnson and her two sons. Williamson, a Philadelphia Quaker, catapulted to national prominence shortly thereafter when he was imprisoned in connec- tion with this rescue. His actions and the corresponding legal pro- 1 Narrative 0} Facts in the Case of Passmore Williamson (Philadelphia, 1855), 3; Case of Passmore Williamson. -

UNITED STATES SECTION ... the BLACK EXPERIENCE in AMERICA SINCE the 17Th CENTURY VOLUME II

Atlanta University-Bell & Howell BLACK CULTURE COLLECTION CATALOG UNITED STATES SECTION ... THE BLACK EXPERIENCE IN AMERICA SINCE THE 17th CENTURY VOLUME II Titles Pro uesf Start here. --- This volume is a finding aid to a ProQuest Research Collection in Microform. To learn more visit: www.proquest.com or call (800) 521-0600 About ProQuest: ProQuest connects people with vetted, reliable information. Key to serious research, the company has forged a 70-year reputation as a gateway to the world's knowledge-from dissertations to governmental and cultural archives to news, in all its forms. Its role is essential to libraries and other organizations whose missions depend on the delivery of complete, trustworthy information. 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway • P.O Box 1346 • Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 • USA •Tel: 734.461.4700 • Toll-free 800-521-0600 • www.proquest.com Copyright 1974 BY BELL & HOWELL FIRST PRINTING, IN THREE VOLUMESo VOL . I AUTHORS January, 1974 VOL. II TITLES February, 1974 VOL. III SUBJECTS (projected-March, 1974 This catalog was printed on 60 lb. PERMALIFE® paper. produced by the Standard Paper Manufacturing Company of Richmond, Virginia. PERMALIFE® was selected for use in this collection because it is an acid-free, chemical-wood, permanent paper with a minimum life expectancy of 300 years. PRINTf.ll IN U.S.A. BY MICRO PHOTO DIV. Bf.I.I. & HOWF.1.1. 01.ll MANSFIEl.I> RD. WOOSTER. OHIO 44691 INIROOUCilON Black Studies is an important subject for mankind, and yet only recently has it been given the attention it so richly deserves. Now, Bell & Howell's Micro Photo Division, with the cooperation of Dr. -

Hannah Crafts and the Bondwoman's Narrative: Rhetoric, Religion, Textual

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2005 Hannah Crafts and The Bondwoman's Narrative: rhetoric, religion, textual influences, and contemporary literary trends and tactics Benjamin Craig Parker Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Benjamin Craig, "Hannah Crafts nda The Bondwoman's Narrative: rhetoric, religion, textual influences, and contemporary literary trends and tactics" (2005). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16264. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16264 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hannah Crafts and The Bondwoman's Narrative: Rhetoric, religion, textual influences, and contemporary literary trends and tactics by Benjamin Craig Parker A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Program of Study Committee: Jane Davis, Major Professor Constance Post Mary Sawyer Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2005 Copyright © Benjamin Craig Parker, 2005. All rights reserved. ii Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Benjamin Craig Parker has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Major Professor For the Major Program 111 Table of Contents Preface ........................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ....... , ........................................................................................4 The Text of The Bondwoman's Narrative and its Rhetorical Tactics ........................... -

In the Shadow of the Civil War: Passmore Williamson and the Rescue of Jane Johnson

Civil War Book Review Winter 2008 Article 12 In the Shadow of the Civil War: Passmore Williamson and the Rescue of Jane Johnson Angela F. Murphy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Murphy, Angela F. (2008) "In the Shadow of the Civil War: Passmore Williamson and the Rescue of Jane Johnson," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol10/iss1/12 Murphy: In the Shadow of the Civil War: Passmore Williamson and the Rescu Review Murphy, Angela F. Winter 2008 Brandt, Nat and Brandt, Yanna Kroyt. In the Shadow of the Civil War: Passmore Williamson and the Rescue of Jane Johnson. University of South Carolina Press, $29.95 hardcover ISBN 9781570036873 A Slave Rescue In the Shadow of the Civil War is a narrative of a slave escape in antebellum Philadelphia and the resulting legal proceedings against an abolitionist who aided in the escape. In 1855 Jane Johnson and her children accompanied their owner, John Hill Wheeler of North Carolina, on a trip that took them through Philadelphia on the way to New York. From New York, Wheeler planned to travel with them to Central America, where Wheeler served as American minister to Nicaragua. Johnson, however, used this sojourn into free territory to liberate herself and her family from Wheeler. Through a network of free blacks in Philadelphia, she contacted the Pennsylvania Vigilance Committee, an arm of the Pennsylvania Antislavery Society, about her wishes. William Still, the famed Underground Railroad organizer who coordinated the committee's activities, engaged Passmore Williamson, a fellow member of the committee and lawyer who often worked on antislavery cases, to aid Johnson in her escape. -

1793 • U.S. Congress Enacts First Fugitive Slave Law Requiring the Return of Fugitives. • Hoping to Build Sympathy for Their

1793 U.S. Congress enacts first fugitive slave law requiring the return of fugitives. Hoping to build sympathy for their citizenship rights, Philadelphia free blacks rally to minister to the sick and maintain order during the yellow fever epidemic. Many blacks fall victim to the disease. 1794 Founding of the American Convention for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, a joining several state and regional antislavery societies into a national organization to promote abolition. Conference held in Philadelphia. The first independent black churches in America (St. Thomas African Episcopal Church and Bethel Church) established in Philadelphia by Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, respectively, as an act of self-determination and a protest against segregation. Congress enacts the federal Slave Trade Act of 1794 prohibiting American vessels to transport slaves to any foreign country from outfitting in American ports. 1797 In the first black initiated petition to Congress, Philadelphia free blacks protest North Carolina laws re-enslaving blacks freed during the Revolution. 1799 A Frenchman residing in Philadelphia is brought before the Mayor, Chief Justice of Federal Court and the Secretary of State for acquiring 130 French uniforms to send to Toussaint L'Overture. 1800 Absalom Jones and other Philadelphia blacks petition Congress against the slave trade and against the fugitive slave act of 1793. Gabriel, an enslaved Virginia black, attempts to organize a massive slave insurrection. Off the coast of Cuba, the U.S. naval vessel Ganges captures two American vessels, carrying 134 enslaved Africans, for violating the 1794 Slave Trade Act and brings them to Philadelphia for adjudication in federal court by Judge Richard Peters.