Hannah Crafts and the Bondwoman's Narrative: Rhetoric, Religion, Textual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MANY Hearts One COMMUNITY Donor Report SPRING 2021 Contents

MANY Hands MANY Hearts One COMMUNITY Donor Report SPRING 2021 Contents 04 ReEnvisioning Critical Care Campaign 06 A Tradition of Generosity 08 Order of the Good Samaritan 18 Good Samaritan of the Year 20 Corporate Honor Roll 24 1902 Club 34 ACE Club 40 Angel Fund 44 Lasting Legacy 48 Gifts of Tribute 50 Special Purpose Funds 54 ReEnvisioning Critical Care Campaign Donors 100% of contributions are used exclusively for hospital projects, programs, or areas of greatest need to better serve the changing healthcare needs of our community. Frederick Health Hospital is a 501(c)(3) not-for-proft organization and all gifts are tax deductible as allowed by law. Message from the President Dear Friends, For over 119 years, members of our community have relied on the staff at Frederick Health to provide care and comfort during their time of need. This has never been more evident than in the past year, as the people of Frederick trusted us to lead the way through the COVID-19 crisis. Driven by our mission to positively impact the well-being of every individual in our community, we have done just that, and I could not be more proud of our healthcare team. Over the past year, all of us at Frederick Health have been challenged in ways we never have been before, but we continue to serve the sick and injured as we always have—24 hours a day, 7 days a week, every day of the year. Even beyond our normal scope of caring for patients, our teams also have undertaken other major responsibilities, including large scale COVID-19 testing and vaccination distribution. -

Scottsdale Arabian Horse Show – February 13‐23, 2020

** Missing Class Numbers ‐ There were NO ENTRIES for these Class Numbers! Scottsdale Arabian Horse Show – February 13‐23, 2020 Results by Class: As of 2/26/2020 Result Back# Horse Name / Breeder Owner Handler Class#1G Arabian Hunter Pleasure JTR 15‐18 10/8/01‐7/31/02 16 Shown Homer‐Brown Rattner Elm 1 793 C SIR TYSON ++/ BARBARA ANN CONNOLLY KARLYN CONNOLLY SIR FAMES HBV X C FELICITY MT VERNON IA 52314 MT VERNON IA 52314 SUSAN MACDONALD 2 517 SOMBRA DO PAI PEGASUS ARABIANS TRISTEN WIKEL BUCHAREST V X ALLIONNES BERLIN HEIGHTS OH 44814 SCOTTSDALE AZ 85260 WIKEL ARABIANS 3 1645 FANFARE WF +/ JOLIE MCGINNIS JOLIE MCGINNIS DESERT HEAT VF +/ X WF FANTAZZI RIO RANCHO NM 87124 RIO RANCHO NM 87124 MARK M AND DEBRA K HELMICK 4 1427 MJM AFIRE CRACKER MUSKAN SANDHU MUSKAN SANDHU BASKE AFIRE X BOGATYNIA NORCO CA 92860 NORCO CA 92860 MIKE OR JOYCE MICALLEF 5 986 LLC PARKER REESE HIGGINS REESE HIGGINS PYRO THYME SA X TC KHARIETA LAMAR MO 64759 LAMAR MO 64759 CLAIRE AND MARGARET LARSON 6 1565 PPINOT NOIR WR LARA MITCHELL LARA MITCHELL PPROVIDENCE X PSYCHES ENVY INVER GROVE HEIGHT MN 5 INVER GROVE HEIGHT MN 55077 MARK OR VALERIE SYLLA 7 1835 MIRAKET Z CORINNA HARRIS CORINNA HARRIS MIRAGE V ++++// X SELKET SINCER PHOENIX AZ 85085 PHOENIX AZ 85085 MICHELE ZINN 8 773 BEATTITUDE BF KYLIE BLAKESLY KYLIE BLAKESLY NOBILISTIC BF X ALADA ATTITUDE CAVE CREEK AZ 85331 CAVE CREEK AZ 85331 BOISVERT FARMS LLC 9 997 MJM DANIELS FIRE MARY CATHERINE BUCHANA MARY CATHERINE BUCHANAN BLACK DANIELS X ETERNAL FIRE PF REDONDO BEACH CA 90277 REDONDO BEACH CA 90277 MIKE OR JOYCE -

The Annotated Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Hollis Robbins A Choose to Read Ohio Toolkit About the Book Declared worthless and dehumanizing by the novelist and critic James Baldwin in 1955, Uncle Tom's Cabin has lacked literary credibility for over fifty years. In this refutation of Baldwin, co-editors Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Hollis Robbins affirm the literary transcendence of Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 masterpiece. As Gates and Robbins underscore, there has never been a single work of fiction that has had a greater effect on American history than Uncle Tom's Cabin . Along with a variety of historical images and an expanded introductory essay, Gates and Robbins have richly edited the original text with hundreds of annotations which illuminate life in the South during nineteenth-century slavery, the abolitionist movement and the influential role played by devout Christians. They also offer details on the life of Harriet Beecher Stowe, the Underground Railroad, Stowe's literary motives, her writing methods, and the novel's wide-ranging impact on the American public. About the Author and Editors Harriet Beecher Stowe is best known for her first book, Uncle Tom's Cabin ( 1852). Begun as a serial for the Washington anti-slavery weekly, the National Era , it focused public interest on the issue of slavery, and was deeply controversial. In writing the book, Stowe drew on personal experience. She was familiar with slavery, the antislavery movement, and the Underground Railroad. Kentucky, across the Ohio River from Cincinnati, Ohio, where Stowe had lived, was a slave state. -

Who Maketh the Clouds His Chariot: the Comparative Method and The

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF RELIGION WHO MAKETH THE CLOUDS HIS CHARIOT: THE COMPARATIVE METHOD AND THE MYTHOPOETICAL MOTIF OF CLOUD-RIDING IN PSALM 104 AND THE EPIC OF BAAL A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF LIBERTY UNIVERSITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES BY JORDAN W. JONES LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA APRIL 2010 “The views expressed in this thesis do not necessarily represent the views of the institution and/or of the thesis readers.” Copyright © 2009 by Jordan W. Jones All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Dr. Don Fowler, who introduced me to the Hebrew Bible and the ancient Near East and who instilled in me an intellectual humility when studying the Scriptures. To Dr. Harvey Hartman, who introduced me to the Old Testament, demanded excellence in the classroom, and encouraged me to study in Jerusalem, from which I benefited greatly. To Dr. Paul Fink, who gave me the opportunity to do graduate studies and has blessed my friends and I with wisdom and a commitment to the word of God. To James and Jeanette Jones (mom and dad), who demonstrated their great love for me by rearing me in the instruction and admonition of the Lord and who thought it worthwhile to put me through college. <WqT* <yx!u&oy br)b=W dos /ya@B= tobv*j&m^ rp@h* Prov 15:22 To my patient and sympathetic wife, who endured my frequent absences during this project and supported me along the way. Hn`ovl=-lu^ ds#j#-tr~otw+ hm*k=j*b= hj*t=P* h*yP! Prov 31:26 To the King, the LORD of all the earth, whom I love and fear. -

Something Akin to Freedom

ሃሁሂ INTRODUCTION I can see that my choices were never truly mine alone—and that that is how it should be, that to assert otherwise is to chase after a sorry sort of freedom. —Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance n an early passage in Toni Morrison’s second novel, Sula (1973), Nel Iand Sula, two young black girls, are accosted by four Irish boys. This confrontation follows weeks in which the girls alter their route home in order to avoid the threatening boys. Although the boys once caught Nel and “pushed her from hand to hand,” they eventually “grew tired of her helpless face” (54) and let her go. Nel’s release only amplifies the boys’ power as she becomes a victim awaiting future attack. Nel and Sula must be ever vigilant as they change their routines to avoid a confrontation. For the boys, Nel and Sula are playthings, but for the girls, the threat posed by a chance encounter restructures their lives. All power is held by the white boys; all fear lies with the vulnerable girls. But one day Sula declares that they should “go on home the short- est way,” and the boys, “[s]potting their prey,” move in to attack. The boys are twice their number, stronger, faster, and white. They smile as they approach; this will not be a fi ght, but a rout—that is, until Sula changes everything: Sula squatted down in the dirt road and put everything down on the ground: her lunch pail, her reader, her mittens, and her slate. -

WILLIAM STILL and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Author(S): Larry Gara Source: Pennsylvania History, Vol

WILLIAM STILL AND THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Author(s): Larry Gara Source: Pennsylvania History, Vol. 28, No. 1 (January, 1961), pp. 33-44 Published by: Penn State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27770004 . Accessed: 09/01/2015 08:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Pennsylvania History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 64.9.56.53 on Fri, 9 Jan 2015 08:30:11 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions WILLIAM STILL AND THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD By Larry Gar a* writer of a popular account of the underground railroad THE in Pennsylvania stated in his preface that "it required the a manhood of man and the unflinching fortitude of a woman, ... to be an abolitionist in those days, and especially an Under was ground Railroad agent/'1 He referring to the noble minority who stood firm when the abolitionists were being "reviled and in persecuted" both the North and the South. Other underground railroad books?some of them written by elderly abolitionists? on put similar emphasis the heroic conductors of the mysterious organization. -

A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28 Annual Conference on American Literature May 25 – 28, 20

American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28th Annual Conference on American Literature May 25 – 28, 2017 The Westin Copley Place 10 Huntington Avenue Boston, MA 02116 Conference Director: Olivia Carr Edenfield Georgia Southern University American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28th Annual Conference on American Literature May 25 – 28, 2017 Acknowledgements: The Conference Director, along with the Executive Board of the ALA, wishes to thank all of the society representatives and panelists for their contributions to the conference. Special appreciation to those good sports who good-heartedly agreed to chair sessions. The American Literature Association expresses its gratitude to Georgia Southern University and its Department of Literature and Philosophy for its consistent support. We are grateful to Rebecca Malott, Administrative Assistant for the Department of Literature and Philosophy at Georgia Southern University, for her patient assistance throughout the year. Particular thanks go once again to Georgia Southern University alumna Megan Flanery for her assistance with the program. We are indebted to Molly J. Donehoo, ALA Executive Assistant, for her wise council and careful oversight of countless details. The Association remains grateful for our webmaster, Rene H. Treviño, California State University, Long Beach, and thank him for his timely service. I speak for all attendees when I express my sincerest appreciation to Alfred Bendixen, Princeton University, Founder and Executive Director of the American Literature Association, for his 28 years of devoted service. We offer thanks as well to ALA Executive Coordinators James Nagel, University of Georgia, and Gloria Cronin, Brigham Young University. -

2018 PA State 4-H Horse Show Results by Class

2018 PA State 4-H Horse Show Results by Class County Exhibitor Animal Class Placing Berks Fedak, Ava Classical Moonlight 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 1st Huntingdon Feagley, Hannah Secure Your Assets 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 2nd Westmoreland McCullough, Abby Harllee 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 3rd Erie Anderson, Madison One Smoking Maverick 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 4th Berks Senseny, Ava Zephyr Woods Treasured Bandit 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 5th Crawford Munsee, Alexa Dudes Mega Winnie 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 6th Fayette Geletko, Rhegynn Ivory 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 7th Columbia Bear, Cove I'm Downright Special 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 8th Dauphin Hack, Ashlee On The Same Page 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 9th Lancaster Grube, Aspen TRF A Trace Of Lace (Lacey) 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 10th Lycoming Moore, Cali Cowgirl Credit 02: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 12-14) 1st Somerset Brehm, Brook Envious Verison 02: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 12-14) 2nd Berks Mayberry, Grace Tiny Tina Turner 02: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 12-14) 3rd Warren Hangge, Alex Hershey 02: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 12-14) 4th Clinton Heverly, Emilee Lil Bonanza Leaguer 02: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 12-14) 5th Westmoreland Macosta, Malaina Just Rock On By 02: English -

Chestnut Filly Barn 3 Hip No

Consigned by Parrish Farms, Agent Barn Hip No. 3 Chestnut Filly 613 Storm Bird Storm Cat ......................... Terlingua Bluegrass Cat ................... A.P. Indy She's a Winner ................. Chestnut Filly Get Lucky February 4, 2008 Fappiano Unbridled.......................... Gana Facil Unbridled Lady ................. (1996) Assert (IRE) Assert Lady....................... Impressive Lady By BLUEGRASS CAT (2003). Black-type winner of $1,761,280, Haskell In- vitational S. [G1] (MTH, $600,000), Remsen S. [G2] (AQU, $120,000), Nashua S. [G3] (BEL, $67,980), Sam F. Davis S. [L] (TAM, $60,000), 2nd Kentucky Derby [G1] (CD, $400,000), Belmont S. [G1] (BEL, $200,000), Travers S. [G1] (SAR, $200,000), Tampa Bay Derby [G3] (TAM, $50,000). Brother to black-type winner Sonoma Cat, half-brother to black-type win- ner Lord of the Game. His first foals are 2-year-olds of 2010. 1st dam UNBRIDLED LADY, by Unbridled. 4 wins at 3 and 4, $196,400, Geisha H.-R (PIM, $60,000), 2nd Carousel S. [L] (LRL, $10,000), Geisha H.-R (PIM, $20,000), Moonlight Jig S.-R (PIM, $8,000), 3rd Maryland Racing Media H. [L] (LRL, $7,484), Squan Song S.-R (LRL, $5,500). Dam of 6 other registered foals, 5 of racing age, 5 to race, 2 winners-- Forestelle (f. by Forestry). 3 wins at 3 and 4, 2009, $63,654. Sun Pennies (f. by Speightstown). Winner in 2 starts at 3, 2010, $21,380. Mared (c. by Speightstown). Placed at 2 and 3, 2009 in Qatar; placed at 3, 2009 in England. 2nd dam ASSERT LADY, by Assert (IRE). -

Acrobat Bounces Back from Life-Threatening Illness to Target Coolmore Stud Stakes | 2 | Thursday, June 10, 2021

ARGENTIA - PAGE 17 Thursday, June 10, 2021 | Dedicated to the Australasian bloodstock industry - subscribe for free: Click here TBA FAST TRACK STUDENTS GRADUATE - PAGE 16 HONG KONG NEWS - PAGE 19 Acrobat bounces back from Read Tomorrow's Issue For life-threatening illness to Maiden of the Week target Coolmore Stud Stakes What's on Race meetings: Gosford (NSW), Ballarat Exciting Fastnet Rock colt on way to Melbourne to start spring (VIC), Pinjarra (AUS), Rockhampton (QLD), preparation with Maher and Eustace New Plymouth (NZ) International race meetings: Haydock (UK), Newbury (UK), Nottingham (UK), Yarmouth (UK), Leopardstown (IRE), ParisLongchamp (FR), International Sales: OBS June 2YOs and Horses of Racing Age (USA) SALES NEWS Member’s Joy sells for Acrobat SPORTPIX $800,000 to shine bright Inglis Millennium (RL, 1200m) raceday at on Inglis Digital BY TIM ROWE | @ANZ_NEWS Randwick, Acrobat suffered a cut to his left Segenhoe Stud are revelling in an inspired crobat (Fastnet Rock), a one- hock while on the walker at trainers Ciaron decision to have stakes-producing time Golden Slipper Stakes (Gr 1, Maher and David Eustace’s Warwick Farm broodmare Members Joy (Hussonet) act as 1200m) favourite and this season’s stables. the shining protagonist in the June (Early) forgotten juvenile, will be given Initially, the injury was not thought to Inglis Digital Sale, as the mare smashed the Athe chance to make up for lost time as a three- be serious and plans were still being made previous Inglis Digital record, and became year-old after winning a remarkable life-and- for the Inglis Nursery (RL, 1000m) winner to the most expensive mare in foal to sell online death battle with illness. -

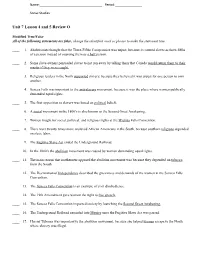

Unit 7 Lesson 4 and 5 Review O

Name:___________________________________ Period:_______________ Social Studies Unit 7 Lesson 4 and 5 Review O Modified True/False All of the following statements are false, change the identified word or phrase to make the statement true. ____ 1. Abolitionists thought that the Three-Fifths Compromise was unjust, because it counted slaves as three-fifths of a person instead of counting them as a half p erson. ____ 2. Some slave owners persuaded slaves to not run away by telling them that Canada w ould return them to their master if they were caught. ____ 3. Religious leaders in the North supported slavery, because they believed it was unjust for one person to own another. ____ 4. Seneca Falls was important to the a nti-slavery movement, because it was the place where women publically demanded equal rights. ____ 5. The first opposition to slavery was based on political beliefs. ____ 6. A social movement in the 1800’s is also known as the Second Great Awakening. ____ 7. Women fought for social, political, and religious rights at the Wichita Falls Convention. ____ 8. There were twenty times more enslaved African Americans in the South, because southern religions depended on slave labor. ____ 9. The Fugitive Slave Act ended the Underground Railroad. ____ 10. In the 1800’s the abolition movement was caused by women demanding equal rights. ____ 11. The main reason that northerners opposed the abolition movement was because they depended on t obacco from the South. ____ 12. The Declaration of I ndependence described the grievances and demands of the women at the Seneca Falls Convention. -

A Comparison of Two Female Slave Narratives Miya Hunter-Willis

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 1-1-2008 Writing the Wrongs : A Comparison of Two Female Slave Narratives Miya Hunter-Willis Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hunter-Willis, Miya, "Writing the Wrongs : A Comparison of Two Female Slave Narratives" (2008). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 658. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Writing the Wrongs: A Comparison of Two Female Slave Narratives Thesis submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History By Miya Hunter-Willis Dr. Robert Sawrey, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Dr. Daniel Holbrook, Ph.D. Dr. Jerome Handler, Ph.D. Marshall University October 2008 ABSTRACT This thesis compares slave narratives written by Mattie J. Jackson and Kate Drumgoold. Both narrators recalled incidents that showed how slavery and the environment during the Reconstruction period created physical and psychological obstacles for women. Each narrator challenged the Cult of True Womanhood by showing that despite the stereotypes created to keep them subordinate there were African American women who successfully used their knowledge of white society to circumvent a system that tried to keep their race enslaved. Despite the 30 years that separate the publication of these two narratives, the legacy of education attainment emerges as a key part of survival and binds the narrators together under a common goal.