Death and Madness in the Bondwoman's Narrative Natalie L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can She Trust You Is a Live, Interactive

Recommended Grades: 3-8 Recommended Length: 40-50 minutes Presentation Overview: Can She Trust You is a live, interactive, distance learning program through which students will interact with the residents of the 1860 Ohio Village to help Rowena, a runaway slave who is searching for assistance along her way to freedom. Students will learn about each village resident, ask questions, and listen for clues. Their objective is to discover which resident is the Underground Railroad conductor and who Rowena can trust. Presentation Outcomes: After participating in this program, students will have a better understanding of the Underground Railroad, various viewpoints on the issue of slavery, and what life was like in the mid-1800s. Standards Connections: National Standards NCTE – ELA K-12.4 Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes. NCTE – ELA K-12.12 Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information). NCSS - SS.2 Time, Continuity, and Change NCSS - SS.5 Individuals, Groups, and Institutions NCSS - SS.6 Power, Authority, and Governance NCSS - SS.8 Science, Technology, and Society Ohio Revised Standards – Social Studies Grade Four Theme: Ohio in the United States Topic: Heritage Content Statement 7: Sectional issues divided the United States after the War of 1812. Ohio played a key role in these issues, particularly with the anti-slavery movement and the Underground Railroad. 1 Topic: Human Systems Content Statement 13: The population of the United States has changed over time, becoming more diverse (e.g., racial, ethnic, linguistic, religious). -

Northern Terminus: the African Canadian History Journal

orthern Terminus: N The African Canadian History Journal Mary “Granny” Taylor Born in the USA in about 1808, Taylor was a well-known Owen Sound vendor and pioneer supporter of the B.M.E. church. Vol. 17/ 2020 Northern Terminus: The African Canadian History Journal Vol. 17/ 2020 Northern Terminus 2020 This publication was enabled by volunteers. Special thanks to the authors for their time and effort. Brought to you by the Grey County Archives, as directed by the Northern Terminus Editorial Committee. This journal is a platform for the voices of the authors and the opinions expressed are their own. The goal of this annual journal is to provide readers with information about the historic Black community of Grey County. The focus is on historical events and people, and the wider national and international contexts that shaped Black history and presence in Grey County. Through essays, interviews and reviews, the journal highlights the work of area organizations, historians and published authors. © 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microreproduction, recording or otherwise – without prior written permission. For copies of the journal please contact the Archives at: Grey Roots: Museum & Archives 102599 Grey Road 18 RR#4 Owen Sound, ON N4K 5N6 [email protected] (519) 376-3690 x6113 or 1-877-473-9766 ISSN 1914-1297, Grey Roots Museum and Archives Editorial Committee: Karin Noble and Naomi Norquay Cover Image: “Owen Sound B. M. E. Church Monument to Pioneers’ Faith: Altar of Present Coloured Folk History of Congregation Goes Back Almost to Beginning of Little Village on the Sydenham When the Negros Met for Worship in Log Edifice, “Little Zion” – Anniversary Services Open on Sunday and Continue All Next Week.” Owen Sound Daily Sun Times, February 21, 1942. -

The Annotated Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Hollis Robbins A Choose to Read Ohio Toolkit About the Book Declared worthless and dehumanizing by the novelist and critic James Baldwin in 1955, Uncle Tom's Cabin has lacked literary credibility for over fifty years. In this refutation of Baldwin, co-editors Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Hollis Robbins affirm the literary transcendence of Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 masterpiece. As Gates and Robbins underscore, there has never been a single work of fiction that has had a greater effect on American history than Uncle Tom's Cabin . Along with a variety of historical images and an expanded introductory essay, Gates and Robbins have richly edited the original text with hundreds of annotations which illuminate life in the South during nineteenth-century slavery, the abolitionist movement and the influential role played by devout Christians. They also offer details on the life of Harriet Beecher Stowe, the Underground Railroad, Stowe's literary motives, her writing methods, and the novel's wide-ranging impact on the American public. About the Author and Editors Harriet Beecher Stowe is best known for her first book, Uncle Tom's Cabin ( 1852). Begun as a serial for the Washington anti-slavery weekly, the National Era , it focused public interest on the issue of slavery, and was deeply controversial. In writing the book, Stowe drew on personal experience. She was familiar with slavery, the antislavery movement, and the Underground Railroad. Kentucky, across the Ohio River from Cincinnati, Ohio, where Stowe had lived, was a slave state. -

Something Akin to Freedom

ሃሁሂ INTRODUCTION I can see that my choices were never truly mine alone—and that that is how it should be, that to assert otherwise is to chase after a sorry sort of freedom. —Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance n an early passage in Toni Morrison’s second novel, Sula (1973), Nel Iand Sula, two young black girls, are accosted by four Irish boys. This confrontation follows weeks in which the girls alter their route home in order to avoid the threatening boys. Although the boys once caught Nel and “pushed her from hand to hand,” they eventually “grew tired of her helpless face” (54) and let her go. Nel’s release only amplifies the boys’ power as she becomes a victim awaiting future attack. Nel and Sula must be ever vigilant as they change their routines to avoid a confrontation. For the boys, Nel and Sula are playthings, but for the girls, the threat posed by a chance encounter restructures their lives. All power is held by the white boys; all fear lies with the vulnerable girls. But one day Sula declares that they should “go on home the short- est way,” and the boys, “[s]potting their prey,” move in to attack. The boys are twice their number, stronger, faster, and white. They smile as they approach; this will not be a fi ght, but a rout—that is, until Sula changes everything: Sula squatted down in the dirt road and put everything down on the ground: her lunch pail, her reader, her mittens, and her slate. -

WILLIAM STILL and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Author(S): Larry Gara Source: Pennsylvania History, Vol

WILLIAM STILL AND THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Author(s): Larry Gara Source: Pennsylvania History, Vol. 28, No. 1 (January, 1961), pp. 33-44 Published by: Penn State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27770004 . Accessed: 09/01/2015 08:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Pennsylvania History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 64.9.56.53 on Fri, 9 Jan 2015 08:30:11 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions WILLIAM STILL AND THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD By Larry Gar a* writer of a popular account of the underground railroad THE in Pennsylvania stated in his preface that "it required the a manhood of man and the unflinching fortitude of a woman, ... to be an abolitionist in those days, and especially an Under was ground Railroad agent/'1 He referring to the noble minority who stood firm when the abolitionists were being "reviled and in persecuted" both the North and the South. Other underground railroad books?some of them written by elderly abolitionists? on put similar emphasis the heroic conductors of the mysterious organization. -

A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28 Annual Conference on American Literature May 25 – 28, 20

American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28th Annual Conference on American Literature May 25 – 28, 2017 The Westin Copley Place 10 Huntington Avenue Boston, MA 02116 Conference Director: Olivia Carr Edenfield Georgia Southern University American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28th Annual Conference on American Literature May 25 – 28, 2017 Acknowledgements: The Conference Director, along with the Executive Board of the ALA, wishes to thank all of the society representatives and panelists for their contributions to the conference. Special appreciation to those good sports who good-heartedly agreed to chair sessions. The American Literature Association expresses its gratitude to Georgia Southern University and its Department of Literature and Philosophy for its consistent support. We are grateful to Rebecca Malott, Administrative Assistant for the Department of Literature and Philosophy at Georgia Southern University, for her patient assistance throughout the year. Particular thanks go once again to Georgia Southern University alumna Megan Flanery for her assistance with the program. We are indebted to Molly J. Donehoo, ALA Executive Assistant, for her wise council and careful oversight of countless details. The Association remains grateful for our webmaster, Rene H. Treviño, California State University, Long Beach, and thank him for his timely service. I speak for all attendees when I express my sincerest appreciation to Alfred Bendixen, Princeton University, Founder and Executive Director of the American Literature Association, for his 28 years of devoted service. We offer thanks as well to ALA Executive Coordinators James Nagel, University of Georgia, and Gloria Cronin, Brigham Young University. -

Hidden Messages in Spirituals Intermediate (Grades 6-8) 1-2 Class Periods

Lesson Plan 1 Hidden Messages in Spirituals Intermediate (grades 6-8) 1-2 class periods Program Segments Coded Lyrics Worksheet Freedom’s Land Coded Lyrics Worksheet - Teacher Notes Student Spiritual Lyrics (teacher should pre-cut and put in box for NYS Core Curriculum - Literacy in History/Social Studies, students to draw from) Science and Technical Subjects, 6-12 “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” Song video (optional) Reading http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Thz1zDAytzU • Craft and Structure (meaning of words) Writing Procedures • Test Types and Purposes (organize ideas, develop topic with 1. Watch the Underground Railroad: The William Still Story segment facts) on spirituals. • Production and Distribution of Writing (develop, organize 2. Explain how spirituals are different from hymns and psalms appropriate to task) because they were a way of sharing the hard condition of being a • Research to Build and Present Knowledge (short research slave. Be sure to discuss the significant dual meanings found in project, using term effectively) the lyrics and their purpose for fugitive slaves (codes, faith). 3. Play the song using an Internet site, mp3 file, or CD. (stopping NCSS Themes periodically to explain parts of the song) I. Culture and Cultural Diversity 4. Have students fill out the Coded Lyrics Worksheet while discussing II. Time, Continuity and Change the meanings as a class. III. People, Places, and Environments 5. Play the song again, uninterrupted. IV. Individual Development and Identity 6. Ask each student to choose a unique line from a box of pre-cut V. Individuals, Groups and Institutions VIII. Science, Technology, and Society Student Spiritual Lyrics. -

Slavery in New Jersey Lesson Plan

Elementary School | Grades 3–5 SLAVERY IN NEW JERSEY ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS What was the Underground Railroad and how did it help enslaved people gain their right of freedom? What role did the people of New Jersey play in the Underground Railroad and the struggle against slavery? OBJECTIVES Students will: → Describe the Underground Railroad and its significance in the abolition of chattel slavery. → Investigate Harriet Tubman’s role as a leader in the Underground Railroad. → Explore New Jersey’s role in the Underground Railroad and map key stops along the route. LEARNING STANDARDS See the standards alignment chart to learn how this lesson supports New Jersey State Standards. TIME NEEDED 45 minutes MATERIALS → AV equipment to show a video → On Track or Off the Rails? handout (one per student or one copy to read aloud) → On Track or Off the Rails Cards handout (copied and cut apart so each student gets one of each card) → Underground Railroad Routes in New Jersey handout (one per student or pair) → New Jersey Stops on the Underground Railroad handout (one per student) VOCABULARY abolitionist enslaver Quaker enslaved plantation Underground Railroad 72 Procedures 2 NOTE ABOUT LANGUAGE When discussing slavery with students, it is suggested the term “enslaved person” be used instead of “slave” to emphasize their humanity; that “enslaver” be used instead of “master” or “owner” to show that slavery was forced upon human beings; and that “freedom seeker” be used instead of “runaway” or “fugitive” to emphasize justice and avoid the connotation of lawbreaking. Write “Underground Railroad” on the board. Ask students if 1 they have ever heard this term and what they know about it. -

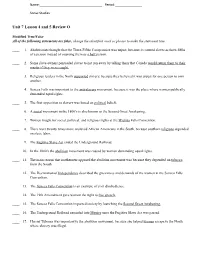

Unit 7 Lesson 4 and 5 Review O

Name:___________________________________ Period:_______________ Social Studies Unit 7 Lesson 4 and 5 Review O Modified True/False All of the following statements are false, change the identified word or phrase to make the statement true. ____ 1. Abolitionists thought that the Three-Fifths Compromise was unjust, because it counted slaves as three-fifths of a person instead of counting them as a half p erson. ____ 2. Some slave owners persuaded slaves to not run away by telling them that Canada w ould return them to their master if they were caught. ____ 3. Religious leaders in the North supported slavery, because they believed it was unjust for one person to own another. ____ 4. Seneca Falls was important to the a nti-slavery movement, because it was the place where women publically demanded equal rights. ____ 5. The first opposition to slavery was based on political beliefs. ____ 6. A social movement in the 1800’s is also known as the Second Great Awakening. ____ 7. Women fought for social, political, and religious rights at the Wichita Falls Convention. ____ 8. There were twenty times more enslaved African Americans in the South, because southern religions depended on slave labor. ____ 9. The Fugitive Slave Act ended the Underground Railroad. ____ 10. In the 1800’s the abolition movement was caused by women demanding equal rights. ____ 11. The main reason that northerners opposed the abolition movement was because they depended on t obacco from the South. ____ 12. The Declaration of I ndependence described the grievances and demands of the women at the Seneca Falls Convention. -

A Comparison of Two Female Slave Narratives Miya Hunter-Willis

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 1-1-2008 Writing the Wrongs : A Comparison of Two Female Slave Narratives Miya Hunter-Willis Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hunter-Willis, Miya, "Writing the Wrongs : A Comparison of Two Female Slave Narratives" (2008). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 658. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Writing the Wrongs: A Comparison of Two Female Slave Narratives Thesis submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History By Miya Hunter-Willis Dr. Robert Sawrey, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Dr. Daniel Holbrook, Ph.D. Dr. Jerome Handler, Ph.D. Marshall University October 2008 ABSTRACT This thesis compares slave narratives written by Mattie J. Jackson and Kate Drumgoold. Both narrators recalled incidents that showed how slavery and the environment during the Reconstruction period created physical and psychological obstacles for women. Each narrator challenged the Cult of True Womanhood by showing that despite the stereotypes created to keep them subordinate there were African American women who successfully used their knowledge of white society to circumvent a system that tried to keep their race enslaved. Despite the 30 years that separate the publication of these two narratives, the legacy of education attainment emerges as a key part of survival and binds the narrators together under a common goal. -

SYMBOLISM in AFRO-AMERICAN SLAVE SONGS THESIS Presented

3 4 I SYMBOLISM IN AFRO-AMERICAN SLAVE SONGS IN THE PRE-CIVIL WAR SOUTH THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Jeannie Chaney Sebastian, B. S. Denton, Texas December, 1976 Sebastian, Jeannie C., Symbolism in Afro-American Slave Songs in the Pre-Civil War South. Master of Science (Speech Communication and Drama), December, 1976. This thesis examines the symbolism of thirty-five slave songs that existed in the pre-Civil War South in the United States in order to gain a more profound insight into the values of the slaves. The songs chosen were representative of the 300 songs reviewed. The methodology used in the analysis was adapted from Ralph K. White's Value Analysis: The Nature and Use of the Method. The slave songs provided the slaves with an opportunity to express their feelings on matters they deemed important, often by using Biblical symbols to "mask" the true meanings of their songs from whites. The major values of the slaves as found in their songs were independence, justice, determination, religion, hope, family love, and group unity. 1976 LINDA JEAN CHANEY SEBASTIAN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES . iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 0 . 1 II. THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF SLAVERY AND SLAVE SONGS . .. 26 III. VALUE ANALYSIS OF THE SLAVE SONGS . 64 IV. THE CONCLUSION . 0 . 91 APPENDIX . 0 0 0 . 98 BIBLIOGRAPHY . S. 0 0 0 .114 iii LIST OF TABLES Table Page I. Frequency Charts . -

Slave Narratives and African American Women’S Literature

UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA Facultad de Filología Departamento de Filología Inglesa HARRIET JACOBS: FORERUNNER OF GENDER STUDIES IN SLAVE NARRATIVES AND AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN’S LITERATURE Sonia Sedano Vivanco 2009 UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA Facultad de Filología Departamento de Filología Inglesa HARRIET JACOBS: FORERUNNER OF GENDER STUDIES IN SLAVE NARRATIVES AND AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN’S LITERATURE Vº Bº Tesis doctoral que presenta SONIA LA DIRECTORA, SEDANO VIVANCO, dirigida por la Dra. OLGA BARRIOS HERRERO Salamanca 2009 UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA Facultad de Filología Departamento de Filología Inglesa HARRIET JACOBS: FORERUNNER OF GENDER STUDIES IN SLAVE NARRATIVES AND AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN’S LITERATURE Sonia Sedano Vivanco 2009 a Manu por el presente a Jimena, Valeria y Mencía por el futuro People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel. (Maya Angelou) Keep in mind always the present you are constructing. It should be the future you want. (Alice Walker) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS When I decided to undertake this project, enthusiasm and passion filled my heart. I did not know then that this would be such a demanding, complex—but at the same time enjoyable and gratifying—enterprise. It has been a long journey in which I have found the support, encouragement and help of several people whom I must now show my gratitude. First of all, I would like to thank Dr. Olga Barrios for all her support, zealousness, and stimulus. The thorough revisions, sharp comments, endless interest, and continuous assistance of this indefatigable professor have been of invaluable help. Thank you also to well-known scholar of African American literature Frances Smith Foster, whose advice in the genesis of this dissertation served to establish a valid work hypothesis.