Northern Terminus: the African Canadian History Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grey Highlands.Indd

photo: Telfer Wegg GREY HIGHLANDS ONTARIO > BLUEWATER REGION • www.greyhighlands.ca • Includes the communities/villages of Eugenia, Feversham, Flesherton, Kimberley, Markdale and Vandeleur • Population: 9,520 Approx. 30 km southeast of Owen Sound; 150 km photo: Telfer Wegg • northwest of Toronto Notable features: • Geographically, the municipality is a mix of villages, hamlets, rural and Small Community heritage communities, and offers a variety of landscapes from agricultural flat lands, to rolling hills and wetlands. • The Niagara Escarpment World Bio Reserve’s runs through the area. • Agriculture forms the basis of the region’s economy. Farms range from small family-owned to large and highly automated HEART OF THE • Mennonite families from Waterloo Region have migrated to Grey Highlands and contribute to the prosperity of the area’s agricultural lifestyle • Businesses also include art galleries—the area has become home to many BEAVER VALLEY artists and musicians The Municipality of Grey Highlands is situated in one of the • Residents have a deep connection to the roots of the municipality with most beautiful parts of Grey County. Made up of the former many local residents descended from the original settlers to the area Townships of Artemesia, Euphrasia, Osprey and the Villages • Agnes Macphail was an early champion of equal rights for women, and of Markdale and Flesherton, the township proudly boast the Canada’s first female MP. She is a local legend, having lived in the Grey natural beauty of waterfalls, the Bruce Trail, the Osprey Bluffs Highlands Municipality and the Saugeen and Beaver Rivers and encompass the “heart • Notable alumni also includes Chris Neil, NHL player (Ottawa Senators) of the Beaver Valley” truly making Grey Highlands the place for all seasons. -

Memphis Jug Baimi

94, Puller Road, B L U E S Barnet, Herts., EN5 4HD, ~ L I N K U.K. Subscriptions £1.50 for six ( 54 sea mail, 58 air mail). Overseas International Money Orders only please or if by personal cheque please add an extra 50p to cover bank clearance charges. Editorial staff: Mike Black, John Stiff. Frank Sidebottom and Alan Balfour. Issue 2 — October/November 1973. Particular thanks to Valerie Wilmer (photos) and Dave Godby (special artwork). National Giro— 32 733 4002 Cover Photo> Memphis Minnie ( ^ ) Blues-Link 1973 editorial In this short editorial all I have space to mention is that we now have a Giro account and overseas readers may find it easier and cheaper to subscribe this way. Apologies to Kees van Wijngaarden whose name we left off “ The Dutch Blues Scene” in No. 1—red faces all round! Those of you who are still waiting for replies to letters — bear with us as yours truly (Mike) has had a spell in hospital and it’s taking time to get the backlog down. Next issue will be a bumper one for Christmas. CONTENTS PAGE Memphis Shakedown — Chris Smith 4 Leicester Blues Em pire — John Stretton & Bob Fisher 20 Obscure LP’ s— Frank Sidebottom 41 Kokomo Arnold — Leon Terjanian 27 Ragtime In The British Museum — Roger Millington 33 Memphis Minnie Dies in Memphis — Steve LaVere 31 Talkabout — Bob Groom 19 Sidetrackin’ — Frank Sidebottom 26 Book Review 40 Record Reviews 39 Contact Ads 42 £ Memphis Shakedown- The Memphis Jug Band On Record by Chris Smith Much has been written about the members of the Memphis Jug Band, notably by Bengt Olsson in Memphis Blues (Studio Vista 1970); surprisingly little, however has got into print about the music that the band played, beyond general outline. -

2014 OHS Annual Report

the Ontario Historical Society ANNUAL REPORT 2 0 1 4 14 the 34 Parkview Avenue Willowdale, Ontario M2N 3Y2 Ontario TEL: 416-226-9011 Historical FAX: 416-226-2740 TOLL-FREE: 1-866-955-2755 Society WEBSITE: www.ontariohistoricalsociety.ca ANNUAL REPORT 2 0 1 4 E-MAIL: [email protected] Ontario Historical Society Annual Meeting, Ottawa, June 2, 1914 15 the Ontario Historical Society ANNUAL REPORT 2 0 1 4 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Joe Stafford, PRESIDENT Chair, Youth Initiatives Committee TABLE OF CONTENTS Caroline Di Cocco, FIRST VICE PRESIDENT Chair, Government Relations Committee Pam Cain, SECOND VICE PRESIDENT 2 PRESIDENT’S REPORT 3 TREASURER’S REPORT B.E.S. (Brad) Rudachyk, PAST PRESIDENT Chair, Nominations Committee 3 - 8 PUBLIC OUTREACH, SERVICES, PROGRAMMES 9 ONTARIO HISTORY Robert (Bob) Leech, TREASURER Chair, Audit & Finance Committee, Investment Committee 10 AFFILIATED SOCIETIES 11 HONOURS AND AWARDS Carolyn King, SECRETARY 12 NEW MEMBERS, SUBSCRIBERS AND DONORS Chair, Preservation Committee Michel Beaulieu, DIRECTOR Chair, Ontario History Committee The Ontario Historical Society, established in 1888, is a non-profit educational corporation, registered charity, and David dos Reis, DIRECTOR Chair, Legal Affairs Committee publisher; a non-government group bringing together people of all ages, all walks of life, and all cultural backgrounds, interested in preserving some aspect of Ontario’s history. Ross Fair, DIRECTOR James Fortin, DIRECTOR Chair, Museums Committee /ONTARIOHISTORICALSOCIETY Allan Macdonell, DIRECTOR Chair, Affiliated Societies Committee @ONTARIOHISTORY Alison Norman, DIRECTOR Chair, Human Resources Committee ONTARIOHISTORICALSOCIETY.CA Ian Radforth, DIRECTOR Chair, Honours & Awards Committee 1 As President, I have been very impressed by the efforts of our affiliated organizations. -

Can She Trust You Is a Live, Interactive

Recommended Grades: 3-8 Recommended Length: 40-50 minutes Presentation Overview: Can She Trust You is a live, interactive, distance learning program through which students will interact with the residents of the 1860 Ohio Village to help Rowena, a runaway slave who is searching for assistance along her way to freedom. Students will learn about each village resident, ask questions, and listen for clues. Their objective is to discover which resident is the Underground Railroad conductor and who Rowena can trust. Presentation Outcomes: After participating in this program, students will have a better understanding of the Underground Railroad, various viewpoints on the issue of slavery, and what life was like in the mid-1800s. Standards Connections: National Standards NCTE – ELA K-12.4 Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes. NCTE – ELA K-12.12 Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information). NCSS - SS.2 Time, Continuity, and Change NCSS - SS.5 Individuals, Groups, and Institutions NCSS - SS.6 Power, Authority, and Governance NCSS - SS.8 Science, Technology, and Society Ohio Revised Standards – Social Studies Grade Four Theme: Ohio in the United States Topic: Heritage Content Statement 7: Sectional issues divided the United States after the War of 1812. Ohio played a key role in these issues, particularly with the anti-slavery movement and the Underground Railroad. 1 Topic: Human Systems Content Statement 13: The population of the United States has changed over time, becoming more diverse (e.g., racial, ethnic, linguistic, religious). -

2019 Civic Directory

Municipality of Grey Highlands 2019 Civic Directory Municipal Office Planning & Building Office Phone: 519-986-2811 206 Toronto Street South 50 Lorne Street Email: [email protected] Unit #1, P.O. Box 409 Markdale, ON Website: www.greyhighlands.ca Markdale, ON N0C 1H0 N0C 1H0 5 t h C o n N o t r h G e r y 2 n R d o a C d o 1 n Grey 8 Road 18 S o u t h Ge rald Short t Pkwy 10 Sideroad 1 2 d y S t S t T h ELMHEDGE Side o L ro w i ad V 6 e i n n n n l BO e i 4 e c h GN n t O R a e h n SEE m Scotch C t INSE - G o T 8 Sideroad Mountain Rd n e r 1 7 Sideroad 7 Sideroad c 1 y 1 e t G h s s 7 Srd R 7 e r t i s t L 3 d h Si C Tucker Street d r i e o ro y a n d d 3 2 L o n e R 9 i n L n o i e T o S MINNIEHILL n a G e M h G e re d e y r R e u d 2 29 M Si 7 t n d a y l ero B h ad e d 3 f o 4 Sideraoad R 4 Sideroad Hurlburt Crt u u E C d f r G o e C R o F o H a e r o i p o r l o l M d lan F a T d n d STRATHNAIRN d - D t s Sy e h g e r o d T en y h 1 a r a v S 1 m i o e w e T n u eow O Duncan 0 n Arthur Taylor Lane n R l l 2 d i w r c n o r r e M s n i s t n s GRIERSV c d ILL h u E S o m n t h a l a e e St W i Field a crest Court R t i n a a l m t h l 2 i H - t ag s i e L n t m S e R n 9 C e r i e L s Lake Shore Road o n a o ne L o a - e l n S n l d a Eu Eastwind Lane c phrasia St Vincent Townl t n ine Ba e W ptist AL d 30th Sideroad Lakewood Drive i s Lane s TER'S Clark St d a o FA V M Collens Crt ASS Hamill LLS Euphrasia- S t Vincent Townl o n R ine e IE t d R T u E t S r Indian Circle 9 h e l Wards Rd e ive Deviation Road Woodland Park Rd e e -

What's Important in Getting on the Destination Wish List

Ontario RTO7 Image Study Final Report February, 2011 Table of Contents Background and Purpose 3 Research Objectives 4 Method 5 Executive Summary 7 Conclusions & Implications 52 Detailed Findings 66 Destination Awareness and Visitation 67 Awareness, Past Visitation and Interest in Local Attractions 159 Awareness/Experience with Grey County Places/Attractions 160 Awareness/Experience with Bruce County Places/Attractions 178 Awareness/Experience with Simcoe County Places/Attractions 199 Interest in Types of Activities/Attractions/Events 220 Image Hot Buttons 243 RTO7’s Image vs. Competitors 246 Image Strengths & Weaknesses vs. Individual Competitors 280 Image Strengths & Weaknesses vs. Individual Competitors — Ontario Residents 320 RTO7’s Competitive Image in Each Region 355 RTO7’s Image by Region of Residence and Demographics 361 RTO7’s Product Delivery 382 Appendix: Questionnaire 389 2 Background & Purpose The Government of Ontario has recently realigned the province’s tourism regions. The new RTO7 region consists of Grey, Bruce and Simcoe Counties. The Region 7 RTO recognizes the importance of tourism to the welfare of the area and has expressed interest in development of a comprehensive strategic plan. As part of this process, Longwoods was engaged to carry out consumer research designed to provide Region 7 with market insights to inform brand strategy development aimed at increasing demand for the region among leisure visitors: Measuring familiarity and experience with the region/its attractions Measuring the region’s image and -

War of 1812 Booklist Be Informed • Be Entertained 2013

War of 1812 Booklist Be Informed • Be Entertained 2013 The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and Great Britain from June 18, 1812 through February 18, 1815, in Virginia, Maryland, along the Canadian border, the western frontier, the Gulf Coast, and through naval engagements in the Great Lakes and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. In the United States frustrations mounted over British maritime policies, the impressments of Americans into British naval service, the failure of the British to withdraw from American territory along the Great Lakes, their backing of Indians on the frontiers, and their unwillingness to sign commercial agreements favorable to the United States. Thus the United States declared war with Great Britain on June 18, 1812. It ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814, although word of the treaty did not reach America until after the January 8, 1815 Battle of New Orleans. An estimated 70,000 Virginians served during the war. There were some 73 armed encounters with the British that took place in Virginia during the war, and Virginians actively fought in Maryland, Virginia, and Ohio and in naval engagements. The nation’s capitol, strategically located off the Chesapeake Bay, was a prime target for the British, and the coast of Virginia figured prominently in the Atlantic theatre of operations. The War of 1812 helped forge a national identity among the American states and laid the groundwork for a national system of homeland defense and a professional military. For Canadians it also forged a national identity, but as proud British subjects defending their homes against southern invaders. -

Appendix ‘C’ Stage 1 Archaeological Assessment TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM

Appendix ‘C’ Stage 1 Archaeological Assessment TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM DATE 23 April 2018 PROJECT No. 1671088-CL-R00 TO Michael S. Troop, P.Eng., M.Eng. J.L. Richards & Associates Ltd. CC Carla Parslow (Golder), Kendra Patton (Golder) FROM Casey O'Neill EMAIL [email protected] ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT - TOWN OF THE BLUE MOUNTAINS MASTER PLAN MUNICIPAL CLASS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR THE COMMUNITY OF CLARKSBURG 1.0 PROJECT CONTEXT 1.1 Development Context The Town of The Blue Mountains (TBM) is undertaking a municipality-wide development Master Planning Municipal Class Environmental Assessment (EA) for future water servicing upgrades. TBM is also undertaking a Master Planning EA for water and waste water infrastructure upgrades within the Clarksburg Service Area, herein the ‘Project Area’. Golder Associates Ltd. (Golder) has prepared this technical memorandum for J.L. Richards & Associates Ltd. (the Client) to summarize archaeological potential in the Village of Clarksburg, based on an archaeological predictive model developed for TBM (Golder 2018a). The Project Area measures approximately 380 ha and is situated within the historic Geographic Township of Collingwood, Grey County, now the Town of The Blue Mountains, Grey County, Ontario (Map 1). 1.1.1 Objectives The objective of this technical memorandum was to use existing information from the larger Stage 1 archaeological assessment and archaeological predictive model prepared for TBM to make statements about archaeological potential specific to the Clarksburg Project Area. The sections below also compile available information about known archaeological resources within the Project Area and provide recommendations for future field survey (i.e., a Stage 2 archaeological assessment), as well as the recommended Stage 2 strategy. -

Richard Pierpoint, Freed Black Loyalist; Served in the American Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 (1744-1837)

Richard Pierpoint, Freed Black Loyalist; Served in the American Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 (1744-1837) Richard Pierpont was born in 1744 in Bundu, in what is now Senegal. When he was approximately 16 years old he was captured and sold to a slave trader. He was sent by ship across the Atlantic Ocean, and having survived the difficult voyage, was sold to a British officer in New England named Pierpoint in 1760. Richard Pierpoint would have acted as the Officer’s personal servant. In his life he was also known as Black Dick and Captain Dick. It is important to note that his African name is unknown, because upon purchase it was discarded and he was given the Christian name Richard. In 1776 the American Revolution broke out, and many African American slaves were offered freedom on the condition that they fought as Loyalists with the British forces. Pierpoint became one of approximately a dozen former black slaves who fought for the British with the Butler’s Rangers, a loyalist battalion located in Fort Niagara, New York. When the British lost the American War of Independence Pierpoint evacuated across the Niagara River to Upper Canada along with scores of fellow loyalists. When he arrived in Canada, he became a free man for the first time since he was 16. Very little is known about Richard Pierpoint’s life. His real name is unknown, no drawings or paintings were made of him, so his appearance is unknown. He never married or had children, and it is unknown whether he could read or write. -

HISTORY 1101A (Autumn 2009) the MAKING of CANADA MRT 218, Monday, 5.30-8.30 P.M

1 HISTORY 1101A (Autumn 2009) THE MAKING OF CANADA MRT 218, Monday, 5.30-8.30 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Jeff Keshen Office: Room 110, 155 Seraphin Marion Office Hours - Monday, 3-5 Phone: 562-5800, ext. 1287 (or by appointment) Fax - 562-5995 e-mail- [email protected] Teaching Assistants - TBA ** FOR A COURSE SYLLABUS WITH ALL LECTURE OUTLINES GO TO: http://www.sass.uottawa.ca/els-sae-shared/pdf/syllabus-history_1101-2009_revised.pdf This course will cover some of the major political, economic, social, and cultural themes in order to build a general understanding of Canadian history. As such, besides examining the lives of prime ministers and other elites, we will also analyse, for example, what things were like for ordinary people; besides focussing upon the French-English divide, we will also look at issues revolving around gender roles and Canada’s First Peoples; and besides noting cultural expressions such as "high art," we will also touch upon things such as various forms of popular entertainment. The general story will come from the lectures. However, your outline will refer to chapters from the Francis, Smith and Jones texts, Journeys. You should read these, especially if parts of the lecture remain unclear. The textbook will provide background; it will not replicate the lectures. Required readings will consist of a series of primary source documents. The lectures will refer to many of those documents, suggesting how they might be understood in relation to the general flow of events. Thus, on the mid-term test and final examination, you should be able to utilize the required readings and the lecture material in responding to questions. -

Chapter 10 Alan C

142 Psychobiographies of Artists Chapter 10 Alan C. Elms & Bruce Heller Twelve Ways to Say “Lonesome” Assessing Error and Control in the Music of Elvis Presley n the current edition of the Oxford English lyrics of “Are You Lonesome Tonight?” . IDictionary (2002), twenty-two usage citations [H]e sweats so much that his face seems to be include the name of Elvis Presley. The two earli- melting away. [T]he dissolving face . est citations, from 1956, show the terms “rock recalls De Palma’s pop-culture horror movie and roll” and “rockin’” in context. A more re- Phantom of the Paradise. (p. 201) cent citation, from a 1981 issue of the British magazine The Listener, demonstrates the usage As an example of biography, Albert Goldman of the word “docudrama”: “In the excellent (1981) concluded his scurrilous best-seller Elvis docudrama film, This Is Elvis, there is a painful with a description of the same scene: sequence . where Elvis . attempts to sing ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight?’” (The ellipses are He is smiling but sweating so profusely that the OED’s.) his face appears to be bathed in tears. Going This Is Elvis warrants the term “docudrama” up on a line in one of those talking bridges because it uses professional actors to re-enact he always had trouble negotiating, he comes scenes from Elvis’s childhood and prefame youth. down in a kooky, free-associative monologue But most of the film is straight documentary. The that summons up the image of the dope- “painful sequence” cited by The Listener and the crazed Lenny Bruce. -

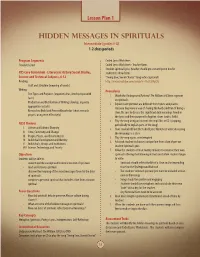

Hidden Messages in Spirituals Intermediate (Grades 6-8) 1-2 Class Periods

Lesson Plan 1 Hidden Messages in Spirituals Intermediate (grades 6-8) 1-2 class periods Program Segments Coded Lyrics Worksheet Freedom’s Land Coded Lyrics Worksheet - Teacher Notes Student Spiritual Lyrics (teacher should pre-cut and put in box for NYS Core Curriculum - Literacy in History/Social Studies, students to draw from) Science and Technical Subjects, 6-12 “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” Song video (optional) Reading http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Thz1zDAytzU • Craft and Structure (meaning of words) Writing Procedures • Test Types and Purposes (organize ideas, develop topic with 1. Watch the Underground Railroad: The William Still Story segment facts) on spirituals. • Production and Distribution of Writing (develop, organize 2. Explain how spirituals are different from hymns and psalms appropriate to task) because they were a way of sharing the hard condition of being a • Research to Build and Present Knowledge (short research slave. Be sure to discuss the significant dual meanings found in project, using term effectively) the lyrics and their purpose for fugitive slaves (codes, faith). 3. Play the song using an Internet site, mp3 file, or CD. (stopping NCSS Themes periodically to explain parts of the song) I. Culture and Cultural Diversity 4. Have students fill out the Coded Lyrics Worksheet while discussing II. Time, Continuity and Change the meanings as a class. III. People, Places, and Environments 5. Play the song again, uninterrupted. IV. Individual Development and Identity 6. Ask each student to choose a unique line from a box of pre-cut V. Individuals, Groups and Institutions VIII. Science, Technology, and Society Student Spiritual Lyrics.