Arbovirus-Related Encephalitis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taxonomy of the Order Bunyavirales: Update 2019

Archives of Virology (2019) 164:1949–1965 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-019-04253-6 VIROLOGY DIVISION NEWS Taxonomy of the order Bunyavirales: update 2019 Abulikemu Abudurexiti1 · Scott Adkins2 · Daniela Alioto3 · Sergey V. Alkhovsky4 · Tatjana Avšič‑Županc5 · Matthew J. Ballinger6 · Dennis A. Bente7 · Martin Beer8 · Éric Bergeron9 · Carol D. Blair10 · Thomas Briese11 · Michael J. Buchmeier12 · Felicity J. Burt13 · Charles H. Calisher10 · Chénchén Cháng14 · Rémi N. Charrel15 · Il Ryong Choi16 · J. Christopher S. Clegg17 · Juan Carlos de la Torre18 · Xavier de Lamballerie15 · Fēi Dèng19 · Francesco Di Serio20 · Michele Digiaro21 · Michael A. Drebot22 · Xiaˇoméi Duàn14 · Hideki Ebihara23 · Toufc Elbeaino21 · Koray Ergünay24 · Charles F. Fulhorst7 · Aura R. Garrison25 · George Fú Gāo26 · Jean‑Paul J. Gonzalez27 · Martin H. Groschup28 · Stephan Günther29 · Anne‑Lise Haenni30 · Roy A. Hall31 · Jussi Hepojoki32,33 · Roger Hewson34 · Zhìhóng Hú19 · Holly R. Hughes35 · Miranda Gilda Jonson36 · Sandra Junglen37,38 · Boris Klempa39 · Jonas Klingström40 · Chūn Kòu14 · Lies Laenen41,42 · Amy J. Lambert35 · Stanley A. Langevin43 · Dan Liu44 · Igor S. Lukashevich45 · Tāo Luò1 · Chuánwèi Lüˇ 19 · Piet Maes41 · William Marciel de Souza46 · Marco Marklewitz37,38 · Giovanni P. Martelli47 · Keita Matsuno48,49 · Nicole Mielke‑Ehret50 · Maria Minutolo3 · Ali Mirazimi51 · Abulimiti Moming14 · Hans‑Peter Mühlbach50 · Rayapati Naidu52 · Beatriz Navarro20 · Márcio Roberto Teixeira Nunes53 · Gustavo Palacios25 · Anna Papa54 · Alex Pauvolid‑Corrêa55 · Janusz T. Pawęska56,57 · Jié Qiáo19 · Sheli R. Radoshitzky25 · Renato O. Resende58 · Víctor Romanowski59 · Amadou Alpha Sall60 · Maria S. Salvato61 · Takahide Sasaya62 · Shū Shěn19 · Xiǎohóng Shí63 · Yukio Shirako64 · Peter Simmonds65 · Manuela Sironi66 · Jin‑Won Song67 · Jessica R. Spengler9 · Mark D. Stenglein68 · Zhèngyuán Sū19 · Sùróng Sūn14 · Shuāng Táng19 · Massimo Turina69 · Bó Wáng19 · Chéng Wáng1 · Huálín Wáng19 · Jūn Wáng19 · Tàiyún Wèi70 · Anna E. -

Notification Requirements

Protocol for Public Health Agencies to Notify CDC about the Occurrence of Nationally Notifiable Conditions, 2021 Categorized by Notification Timeliness IMMEDIATELY NOTIFIABLE, EXTREMELY URGENT: Call the CDC ROUTINELY NOTIFIABLE: Submit electronic case notification Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770.488.7100 within 4 hours of within the next reporting cycle. a case meeting the notification criteria, followed by submission of an electronic case notification to CDC by the next business day. IMMEDIATELY NOTIFIABLE, URGENT: Call the CDC EOC at 770.488.7100 Approved by CSTE: June 2019 within 24 hours of a case meeting the notification criteria, followed by Interim Update Approved by CSTE: April 5, 2020 submission of an electronic case notification in next regularly scheduled Implemented: January 1, 2020 electronic transmission. Updated: May 28, 2020 Condition Notification Timeliness Cases Requiring Notification Anthrax Immediately notifiable, Confirmed and probable cases - Source of infection not recognized extremely urgent - Recognized BT exposure/potential mass exposure - Serious illness of naturally-occurring anthrax Botulism Immediately notifiable, All cases prior to classification - Foodborne (except endemic to Alaska) extremely urgent - Intentional or suspected intentional release - Infant botulism (clusters or outbreaks) - Cases of unknown etiology/not meeting standard notification criteria Page 1 of 5 Plague Immediately notifiable, All cases prior to classification - Suspected intentional release extremely urgent Paralytic poliomyelitis -

2018 DSHS Arbovirus Activity

Health and Human Texas Department of State Services Health Services Arbovirus Activity in Texas 2018 Surveillance Report August 2019 Texas Department of State Health Services Zoonosis Control Branch Overview Viruses transmitted by mosquitoes are referred to as arthropod-borne viruses or arboviruses. Arboviruses reported in Texas may include California (CAL) serogroup viruses, chikungunya virus (CHIKV), dengue virus (DENV), eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV), Saint Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV), western equine encephalitis virus (WEEV), West Nile virus (WNV), and Zika virus (ZIKV), many of which are endemic or enzootic in the state. In 2018, reported human arboviral disease cases were attributed to WNV (82%), DENV (11%), CHIKV (4%), ZIKV (2%), and CAL (1%) (Table 1). In addition, there were two cases reported as arbovirus disease cases which could not be diagnostically or epidemiologically differentiated between DENV and ZIKV. Animal infections or disease caused by WNV and SLEV were also reported during 2018. Local transmission of DENV, SLEV, and WNV was documented during 2018 (Figure 1). No reports of EEEV or WEEV were received during 2018. Table 1. Year-End Arbovirus Activity Summary, Texas, 2018 Positive Human* Arbovirus Mosquito Avian Equine TOTAL TOTAL Fever Neuroinvasive Severe Deaths PVD‡ Pools (Human) CAL 1 1 1 CHIK 7 7 7 DEN 20 20 20 SLE 2 0 2 WN 1,021 6 19 38 108 146 11 24 1,192 Zika** 4 4 TOTAL 1,023 6 19 65 109 0 178 11 24 1,226 CAL - California serogroup includes California encephalitis, Jamestown Canyon, Keystone, La Crosse, Snowshoe hare and Trivittatus viruses CHIK - Chikungunya DEN - Dengue SLE - Saint Louis encephalitis WN - West Nile ‡PVD - Presumptive viremic blood donors are people who had no symptoms at the time of donating blood through a blood collection agency, but whose blood tested positive when screened for the presence of West Nile virus or Zika virus. -

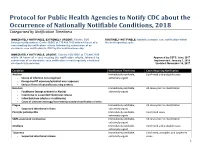

Protocol for Public Health Agencies to Notify CDC About the Occurrence of Nationally Notifiable Conditions, 2018 Categorized by Notification Timeliness

Protocol for Public Health Agencies to Notify CDC about the Occurrence of Nationally Notifiable Conditions, 2018 Categorized by Notification Timeliness IMMEDIATELY NOTIFIABLE, EXTREMELY URGENT: Call the CDC ROUTINELY NOTIFIABLE: Submit electronic case notification within Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770.488.7100 within 4 hours of a the next reporting cycle. case meeting the notification criteria, followed by submission of an electronic case notification to CDC by the next business day. IMMEDIATELY NOTIFIABLE, URGENT: Call the CDC EOC at 770.488.7100 within 24 hours of a case meeting the notification criteria, followed by Approved by CSTE: June 2017 submission of an electronic case notification in next regularly scheduled Implemented: January 1, 2018 electronic transmission. Updated: November 16, 2017 Condition Notification Timeliness Cases Requiring Notification Anthrax Immediately notifiable, Confirmed and probable cases - Source of infection not recognized extremely urgent - Recognized BT exposure/potential mass exposure - Serious illness of naturally-occurring anthrax Botulism Immediately notifiable, All cases prior to classification - Foodborne (except endemic to Alaska) extremely urgent - Intentional or suspected intentional release - Infant botulism (clusters or outbreaks) - Cases of unknown etiology/not meeting standard notification criteria Plague Immediately notifiable, All cases prior to classification - Suspected intentional release extremely urgent Paralytic poliomyelitis Immediately notifiable, Confirmed cases extremely -

Taxonomy of the Family Arenaviridae and the Order Bunyavirales: Update 2018

Archives of Virology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-018-3843-5 VIROLOGY DIVISION NEWS Taxonomy of the family Arenaviridae and the order Bunyavirales: update 2018 Piet Maes1 · Sergey V. Alkhovsky2 · Yīmíng Bào3 · Martin Beer4 · Monica Birkhead5 · Thomas Briese6 · Michael J. Buchmeier7 · Charles H. Calisher8 · Rémi N. Charrel9 · Il Ryong Choi10 · Christopher S. Clegg11 · Juan Carlos de la Torre12 · Eric Delwart13,14 · Joseph L. DeRisi15 · Patrick L. Di Bello16 · Francesco Di Serio17 · Michele Digiaro18 · Valerian V. Dolja19 · Christian Drosten20,21,22 · Tobiasz Z. Druciarek16 · Jiang Du23 · Hideki Ebihara24 · Toufc Elbeaino18 · Rose C. Gergerich16 · Amethyst N. Gillis25 · Jean‑Paul J. Gonzalez26 · Anne‑Lise Haenni27 · Jussi Hepojoki28,29 · Udo Hetzel29,30 · Thiện Hồ16 · Ní Hóng31 · Rakesh K. Jain32 · Petrus Jansen van Vuren5,33 · Qi Jin34,35 · Miranda Gilda Jonson36 · Sandra Junglen20,22 · Karen E. Keller37 · Alan Kemp5 · Anja Kipar29,30 · Nikola O. Kondov13 · Eugene V. Koonin38 · Richard Kormelink39 · Yegor Korzyukov28 · Mart Krupovic40 · Amy J. Lambert41 · Alma G. Laney42 · Matthew LeBreton43 · Igor S. Lukashevich44 · Marco Marklewitz20,22 · Wanda Markotter5,33 · Giovanni P. Martelli45 · Robert R. Martin37 · Nicole Mielke‑Ehret46 · Hans‑Peter Mühlbach46 · Beatriz Navarro17 · Terry Fei Fan Ng14 · Márcio Roberto Teixeira Nunes47,48 · Gustavo Palacios49 · Janusz T. Pawęska5,33 · Clarence J. Peters50 · Alexander Plyusnin28 · Sheli R. Radoshitzky49 · Víctor Romanowski51 · Pertteli Salmenperä28,52 · Maria S. Salvato53 · Hélène Sanfaçon54 · Takahide Sasaya55 · Connie Schmaljohn49 · Bradley S. Schneider25 · Yukio Shirako56 · Stuart Siddell57 · Tarja A. Sironen28 · Mark D. Stenglein58 · Nadia Storm5 · Harikishan Sudini59 · Robert B. Tesh48 · Ioannis E. Tzanetakis16 · Mangala Uppala59 · Olli Vapalahti28,30,60 · Nikos Vasilakis48 · Peter J. Walker61 · Guópíng Wáng31 · Lìpíng Wáng31 · Yànxiăng Wáng31 · Tàiyún Wèi62 · Michael R. -

DSHS Arbovirus Activity 061817

Arbovirus Activity in Texas 2017 Surveillance Report June 2018 Texas Department of State Health Services Infectious Disease Control Unit Zoonosis Control Branch Overview Viruses transmitted by mosquitoes are referred to as arthropod-borne viruses or arboviruses. Arboviruses reported in Texas may include California serogroup viruses (CAL), chikungunya virus (CHIKV), dengue virus (DENV), eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV), Saint Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV), western equine encephalitis virus (WEEV), West Nile virus (WNV), and Zika virus (ZIKV), many of which are endemic or enzootic in the state. In 2017, reported human arboviral disease cases were attributed to WNV (54%), ZIKV (22%), DENV (17%), and CHIKV (6%) (Table 1). Animal infections or disease caused by CAL, EEEV, SLEV, and WNV were also reported during 2017. Table 1. Year-End Arbovirus Activity Summary, Texas, 2017 California Serogroup Viruses California serogroup viruses (CAL) are bunyaviruses and include California encephalitis virus (CEV), Jamestown Canyon virus, Keystone virus, La Crosse virus (LACV), snowshoe hare virus, and Trivittatus virus. These viruses are maintained in a cycle between mosquito vectors and vertebrate hosts in forest habitats. In the United States (U.S.), approximately 80-100 reported cases of human neuroinvasive disease are caused by LACV each year (CDC), mostly in mid-Atlantic and southeastern states. From 2002-2016, Texas reported a total of 5 cases of human CAL disease (range: 0-3 cases/year): 1 case of CEV neuroinvasive disease and 4 cases of LACV neuroinvasive disease. In 2017, one CEV-positive mosquito pool was identified in Orange County (Figure 1); no human cases of CAL disease were reported. -

The History of Public Entomology at the Connecticut Agricultural

The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station The History of Public Health Entomology at The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 1904 –2009 JOHN F. ANDERSON, Ph.D. Distinguished Scientist Emeritus, Department of Entomology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station The History of Public Health Entomology at The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 1904 –2009 JOHN F. ANDERSON, Ph.D. Distinguished Scientist Emeritus, Department of Entomology Funded, in part, by The Experiment Station Associates Bulletin 1030 2010 Acknowledgments This publication is in response to citizen requests that I write an Experiment Station publication of my talk entitled, “104 Years of Public Health Entomology at The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station.” I gave this presentation in New Haven at an open house event in the spring of 2008. I express my sincere appreciation to Bonnie Hamid, who formatted the complex figures and the entire text and provided assistance with library searches and the writing. Vickie Bomba-Lewandoski assisted with acquiring some of the historical publications and scanning some of the photographs. Dr. Toby Anita Appel, John R. Bumstead Librarian for Medical History, and Florence Gillich, Historical Medical Library Assistant at the Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library, Yale University, assisted me with locating critical publications, as did Suzy Taraba, University Archivist and Head of Special Collections at Olin Library, Wesleyan University, and Professor Durland Fish, Yale University. James W. Campbell, Librarian and Curator of Manuscripts at the New Haven Museum sent me a copy of the New Haven Chronicle masthead (Figure 7). The extraordinary efforts of Mr. David Miles, photographer, Mr. Andrew Rogalski, Technical Services Librarian, and Terrie Wheeler, Chief Librarian, Gorgas Memorial Library, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, in providing the superb image of Dean Cornwell’s painting entitled “Conquerors of Yellow Fever” (Figure 12) are greatly appreciated. -

Quick View Reportable Disease List

STOPIllinois Department of Public Health and Report Infectious Disease Illinois Reportable Diseases Mandated reporters, such as health care providers, hospitals and laboratories, must report suspected or confirmed cases of these diseases to the local health department. Diseases in bold are reportable within 24 hours. Diseases marked "immediate" (or in red) are reportable as soon as possible within 3 hours. All other conditions not in red or bold are reportable within 7 days. Anaplasmosis Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome Reye's syndrome Any suspected bioterrorist threat (immediate) Hemolytic uremic syndrome, post diarrheal Rubella Any unusual case or cluster of cases that may Hepatitis A St. Louis Encephalitis virus indicate a public health hazard (immediate) Hepatitis B, C, D Salmonellosis, other than typhoid Anthrax (immediate) Pregnant hepatitis B carrier Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Arboviruses (including WNV) Histoplasmosis (immediate) Babesiosis HIV infection Shigellosis Botulism, foodborne (immediate) Influenza, deaths in <18 yr olds Smallpox (immediate) Botulism, infant, wound, other Influenza A, novel (immediate) Smallpox vaccination, complications of Brucellosis* Influenza, ICU admissions Snowshoe hare virus California Encephalitis virus Jamestown Canyon virus Spotted fever rickettsioses Campylobacteriosis Keystone virus S. aureus infections with intermediate or high Candida auris** La Crosse virus level resistance to vancomycin Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae Legionellosis Streptococcal infections, Group A, -

Status of Resistant of Dengue, Yellow Fever, Chikungunya, Zika Vectors to Different Insecticides in Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO) and Indian Subcontinent

Research Article ISSN: 2574 -1241 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2021.35.005660 Status of Resistant of Dengue, Yellow Fever, Chikungunya, Zika Vectors to different Insecticides in Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO) and Indian Subcontinent Hassan Vatandoost1,2*, Ahmad Ali Hanafi-Bojd1, Fatemeh Nikpoor2 and Tahereh Sadat Asgarian1 1Department of Medical Entomology & Vector Control, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran 2Department of Chemical Pollutants and Pesticides, Institute for Environmental Research, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran *Corresponding author: Hassan Vatandoost, Department of Medical Entomology & Vector Control, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: April 09, 2021 Vector-borne diseases transmitted by insect vectors such as mosquitoes occur in over 100 countries and affect almost half of the world’s population. Dengue is currently Published: April 19, 2021 the deadliest arboviral disease but chikungunya and Zika show increasing prevalence and severity. Vector control, mainly by the use of insecticides, play a key role in disease prevention but the use of the same chemicals for more than 40 years, together with Citation: Hassan Vatandoost, Ahmad Ali the dissemination of mosquitoes by human activities, resulted in the global spread of insecticide resistance. In this context, innovative tools and strategies for vector control Sadat Asgarian. Status of Resistant of are urgently needed. Arboviruses transmitted by mosquitoes represent a major health Hanafi-Bojd, Fatemeh Nikpoor, Tahereh problem in EMRO countries. The main vector control activities include larviciding, space Vectors to different Insecticides in Eastern spraying, impregnated bednet and indoor residual spraying. The susceptibility status of MediterraneanDengue, Yellow Region Fever, (EMRO)Chikungunya, and Indian Zika the two main vectors of Arboviruses, Aedes aegypti and Ae. -

Chris Ray University of Colorado, USA

00-Collinge-Prelims.qxd 24/12/05 07:37 AM Page i Disease Ecology This page intentionally left blank Disease Ecology Community structure and pathogen dynamics edited by Sharon K. Collinge and Chris Ray University of Colorado, USA 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Oxford University Press 2006 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Disease ecology / edited by Sharon K. -

Illinois Reportable Disease Poster

STOPIllinois Department of Public Health and Report Infectious Disease Illinois Reportable Diseases Mandated reporters, such as health care providers, hospitals and laboratories, must report suspected or confirmed cases of these diseases to the local health department. Diseases in bold are reportable within 24 hours. Diseases marked "immediate" (or in red) are reportable as soon as possible within 3 hours. All other conditions not in red or bold are reportable within 7 days. Anaplasmosis Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome Reye's syndrome Any suspected bioterrorist threat (immediate) Hemolytic uremic syndrome, post diarrheal Rubella Any unusual case or cluster of cases that may Hepatitis A St. Louis Encephalitis virus indicate a public health hazard (immediate) Hepatitis B, C, D Salmonellosis, other than typhoid Anthrax (immediate) Pregnant hepatitis B carrier Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Arboviruses (including WNV) Histoplasmosis (immediate) Babesiosis HIV infection Shigellosis Botulism, foodborne (immediate) Influenza, deaths in <18 yr olds Smallpox (immediate) Botulism, infant, wound, other Influenza A, novel (immediate) Smallpox vaccination, complications of Brucellosis* Influenza, ICU admissions Snowshoe hare virus California Encephalitis virus Jamestown Canyon virus Spotted fever rickettsioses Campylobacteriosis Keystone virus S. aureus infections with intermediate or high Candida auris** La Crosse virus level resistance to vancomycin Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae Legionellosis Streptococcal infections, Group A, -

Changing Patterns in Mosquito-Borne Arboviruses

Dncnrvrnnn.1986 Mosqurro-BoRNE ARBovTRUSES 437 CHANGING PATTERNS IN MOSQUITO-BORNE ARBOVIRUSES G. R. DEFOLIARTT. D. M. WATTS' eNo P. R. GRIMSTAD3 ABSTRACT. Researchleading to the current state of knowledge on the epidemiology of La Crossevirus (LACV),JamestownCanyon virus (JCV) and dengue(DEN) virusesis summarizedin relationto the generally recognizCdcriteria for incriminating vectors.The importance of vector biology and local ecologicalconditions is eriphasized as is the necessityofi good balanceb6tween laboratory and fiIld-based studies.The influence of huinan activity in shaping th'e epidemiologicalpatterns of all three'of these arbovirusesis readily apparent. INTRODUCTION such,the suddenlyvoluminous research on this virus and its major vector, Aedzstriserintus (Say), Four basiccriteria must be met in incriminat- is relatively condensedin time compared to any ing the mosquito vector(s)of an arbovirus: l) other arbovirus. It illusrates the types of isolation of virus from naturally infected questions raised in investigating a virus known mosquitoes;2) laboratory demonsration of the to be transovarially transmitted in nature. ability of the mosquitoesto become infected by Jamestown Canyon virus appears to be the feeding on a viremic host; 3) laboratory most rapidly emerging "new" arboviral prob- demonstration of the ability of these infected lem of public health importance in North mosquitoes to transmit the virus during America. Although serologicallyclose to LACV, bloodfeeding,and ; 4) evidenceof bloodfeeding its ecological support system (i.e., vectors, contact between the suspectedmosquito vector vertebratehosts, landscape) is completelydif- and suspectedvertebrate hosts under natural ferent. Despite this, these two viruses interface conditions. In a companion review (DeFoliart in intricate ways that carry potentially impor- et al.