Official Urban Naming: Cultural Heritage and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anason Family in Rogaland County, Norway and Juneau County, Wisconsin Lawrence W

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Faculty Publications Library Faculty January 2013 The Anason Family in Rogaland County, Norway and Juneau County, Wisconsin Lawrence W. Onsager Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/library-pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Onsager, Lawrence W., "The Anason Family in Rogaland County, Norway and Juneau County, Wisconsin" (2013). Faculty Publications. Paper 25. http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/library-pubs/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Faculty at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ANASON FAMILY IN ROGALAND COUNTY, NORWAY AND JUNEAU COUNTY, WISCONSIN BY LAWRENCE W. ONSAGER THE LEMONWEIR VALLEY PRESS Berrien Springs, Michigan and Mauston, Wisconsin 2013 ANASON FAMILY INTRODUCTION The Anason family has its roots in Rogaland County, in western Norway. Western Norway is the area which had the greatest emigration to the United States. The County of Rogaland, formerly named Stavanger, lies at Norway’s southwestern tip, with the North Sea washing its fjords, beaches and islands. The name Rogaland means “the land of the Ryger,” an old Germanic tribe. The Ryger tribe is believed to have settled there 2,000 years ago. The meaning of the tribal name is uncertain. Rogaland was called Rygiafylke in the Viking age. The earliest known members of the Anason family came from a region of Rogaland that has since become part of Vest-Agder County. -

Sports Manager

Stavanger Svømme Club and Madla Svømmeklubb were merged into one swimming club on the 18th of April 2018. The new club, now called Stavanger Svømmeklubb, is today Norway's largest swimming club with 4000 members. The club that was first founded in 1910 has a long and proud history of strong traditions, defined values and solid economy. We are among the best clubs in Norway with participants in international championships (Olympics, World and European Championships). The club give children, youngsters, adults and people with disabilities the opportunity to learn, train, compete and develop in a safe, healthy and inclusive environment. The club has a general manager, an office administrator, a swimming school manager, 7 full-time coaches, as well as a number of group trainers and swimming instructors. The main goal for Stavanger Svømmeklubb is that we want be the preferred swimming club in Rogaland County and a swimming club where the best swimmers want to be. Norway's largest swimming club is seeking a Sports Manager Stavanger Svømmeklubb is seeking an experienced, competent and committed sports manager for a full time position that can broaden, develop and strengthen the club's position as one of the best swimming clubs in Norway. The club's sports manager will be responsible for coordinating, leading and implementing the sporting activity of the club, as well as having the professional responsibility and follow-up of the club's coaches. The sports manager should have knowledge of Norwegian swimming in terms of structure, culture and training philosophy. The job involves close cooperation with other members of the sports committee, general manager and coaches to develop the club. -

Kyrkjeblad for Hjelmeland, Fister, Årdal, Strand, Jørpeland Og Forsand Sokn Nr.4, Oktober 2020

Preikestolen Preikestolen Preikestolen Preikestolen KYRKJEBLAD FOR HJELMELAND, FISTER, ÅRDAL, STRAND, JØRPELAND OG FORSAND SOKN NR.4, OKTOBER 2020. 81. ÅRG. Preikestolen for å oppsøkje stader med mange folk? Engstelse, glede, sorg, sinne, Preikestolen Korleis skal me få påfyll i denne takknemlegheit. Han tek imot og Innhald nr. 4-2020: annleis - hausten? Det kan kjennast rommar det. tungt at ting er annleis. Kanskje er det Skund deg og kom ned, sa Jesus til Adresse: fleire spørsmål enn svar? Sakkeus. For i dag vil eg ta inn i ditt Postboks 188 Å forma det heilage................................................................... Side 4 Om me er heime eller ute, så ynskjer hus. Skund deg og kom, seier Jesus til 4126 Jørpeland Altertavla i Forsand kyrkje....................................................... Side 7 Gud å kome oss i møte i livet slik det oss. I dag vil eg ta inn i ditt hus. Sorg og tap................................................................................. Side 8 Neste nummer av Det gode er, ikkje slik det «burde» vere. Preikestolen kjem Ung sorg..................................................................................... Side 10 i postkassen Å dele tro og liv på tvers av generasjoner.............................. Side 12 ca. 01. Pdesember.reikestolen møte Frist for innlevering av Turist-åpen kirke........................................................................ Side 14 stoff er 30. oktober. Et minne fra Badger Iowa......................................................... Side 15 Kyrke i korona-tid..................................................................... -

Menighetsbladet 1 2018 V4.Indd 1 12.03.2018 16:16:30 Tom Grav Og Trassig Tru

Levende Jesustro i livsnære fellesskap menighetsNR 1 - 2018 HØYLAND I HELG OGbladet HVERDAG Frivillige hyllet for innsatsen Side 7 Faste for vann Side 5 Takker Ny for seg konfirmantleir Side 4 Side 3 menighetsbladet_1_2018_v4.indd 1 12.03.2018 16:16:30 Tom grav og trassig tru I oktober var eg på rundreise med opptoget med dei tre på veg til belhistoriane, anten me les dei , høyrer å bli krossfesta. Her var det eit kaotisk dei eller er på dei heilage stadane i Is- i Israel og Palestina saman opptog med hat og kjærleik, jubel og rael og Palestina. Den tome grava sikrar med ei turguppe. Det er gråt. oss eit guddommeleg håp. Ei enkel og spesielt å reisa inn i bibelhis- Likevel: Midt i alt dette, både den trassig tru bær med seg dette håpet gong og seinare, var det eit guddom- i møte med det samansette livet som toriane me har lest og høyrt meleg nærvær. Himmelens Gud ville både kan kjennast kaotisk og harmon- mange gonger. endra verden og skapa noko nytt gjen- isk. Påskedrama sprenger veg gjennom nom kaoset og dei forskjellige ropa. Via døden og opnar ein guddommeleg di- Kva er det spesielle? Dolorosa formidlar noko av dette gjen- mensjon som er større enn det tanken 1. Det er spesielt å sjå alle kyrkjer og nom butikkar og trengsel av folk. og fornuften kan ta inn. minnesmerker som er reist på dei hei- 4. Sterkast var det likevel å vera i I møte med den tome grava syng lage stadane. Jesushistoriane har sett så gravhagen. -

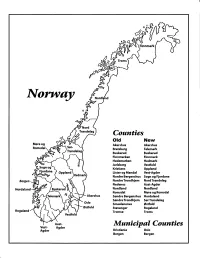

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Revheim KLIMAANALYSE Plan 2424

MADLA - REVHEIM KLIMAANALYSE Plan 2424. Områdeplan for Madla - Revheim 14.05.2012 Konsulent: ASPLAN VIAK AS 1 1 DOKUMENTINFORMASJON Oppdragsgiver: Stavanger Kommune Rapporttittel: Klimaanalyse for plan 2424 Madla - Revheim Utgave/dato: 2 / 2012-05-14 Arkivreferanse: - Lagringsnavn rapport Oppdrag: 529216 – Lokalklimaanalyse for Madla-Revheim, Stavanger Oppdragsbeskrivelse: (Basert på tilbud 011763): Lokalklimaanalyse som grunnlag for arkitektkonkurranse Oppdragsleder: Rieck Nina Fag: Arkitektur;Landskap;Plan Tema Bolig;By- og tettstedsutvikling Leveranse: Analyse Skrevet av: Nina Rieck og Kjersti Tau Strand Kvalitetskontroll: Hanne C. Jonassen Asplan Viak AS www.asplanviak.no Stavanger Kommune Asplan Viak AS 2 FORORD I forbindelse med det pågående arbeidet med utarbeidelse av områdeplan for Madla- Revheim (plan 2424), er det utført en lokalklimavurdering på oppdrag for Stavanger kommune ved kultur og byutvikling. Madla-Revheim skal utvikles til en fremtidsrettet og klimavennlig bydel optimalt tilpasset landskapet, tilgrensende jordbruksvirksomhet og beliggenheten i det regionale bysystemet. Lokalklimavurderingen redegjør for de lokalklimatiske forholdene på Madla-Revheim, hvordan lokalklimaet vil kunne bli endret og påvirke planområdet, og hva som bør tas hensyn til i den videre planleggingen. Analysen vil også gi anbefalinger om hvilke områder som er egnet/mindre egnet til utbygging, og hvilke prinsipper og strukturer som bør legges til grunn i de ulike områdene. Det er ikke utført meteorologiske målinger i planområdet. Modelldata fra vindkart for Norge er benyttet for å beskrive vind- og inversjonsforholdene på Madla-Revheim. Analysen er gjennomført i samarbeid mellom Asplan Viak ved Nina Rieck (oppdragsleder) og Kjersti Tau Strand og Kjeller Vindteknikk ved David Edward Weir. Tor Nestande (Asplan Viak) har hatt ansvar for kart- og tegningsproduksjon. -

The Know Norwaybook

International and Comparative Studies in Education and Public Information Norway is a country of winter darkness and midnight sun, advanced technology, small towns and a few cities. It has a big The Know NORWAY Book government sector, free education and Background for Understanding the Country and Its People health services, and a modern and dynamic private sector. Pakistan and Afghanistan Edition Norway is home to large communities of Pakistani, Afghan and other immigrants and refugees. Norway is one of the world’s richest and most egalitarian societies. The country’s beauty has made tourism a major income-earner, and fishing, shipping and shipbuilding industries are still important. In the last generation, North Sea oil and gas production has made Norway one of the world’s largest oil exporters – and the Norwegians are now nicknamed “the blue-eyed sheikhs”. PRINTED IN PAKISTAN Mr.Books Atle Hetland Mr.Books Sang-e-Meel Sang-e-Meel The Know NORWAY Book Background for Understanding the Country and Its People Pakistan and Afghanistan Edition Atle Hetland Published in 2010 by Mr. Books Publishers and Booksellers, Islamabad, Pakistan www.mrbook.com.pk ISBN 969-516-166-9 This book, or part thereof, may not be reproduced in print or electronlic form without the permission from the author. Sections may, however, be reproduced for internal use by educational and research institutions and organizations, with reference given to the book. Copyright © Atle Hetland 2010 All rights reserved Author: Atle Hetland English Language and Editorial Consultant: Fiona Torrens-Spence Graphic Artist and Design: Salman Beenish Views expressed and analyses in this publication are those of the author. -

Da Oljå Kom Til Byen Og Rosenberg

Arbeidernes ÅRBOK_Layout 1 25.07.13 11.00 Side 100 Da oljå kom til byen og Rosenberg GUNNAR BERGE Mange i Stavanger og i landet ellers spør om hva vi skal Det hører med til historien at vinteren 1964 var bikkje- leve av etter oljå. På 1960-tallet var spørsmålet: Hva skal kald i Stavanger. Minus 10 grader i lange perioder og vi leve av når Sigvald Bergesen d.y. ikke lengre kan bygge kuling. Det ble en del unnaluring. Et yndet tilfluktssted store tankskip på Rosenberg? I dag vet vi at uten oljå ville var å gå på do. Der var riktig nok øverste del av dørene neppe Rosenberg ha overlevd. saget av slik at det var mulig å føre kontroll. Det var dog ikke mulig å se hvem som hadde buksene på og hvem som Etter en enestående glansperiode fra 1950, da kjølen til satt der i lovlig ærend. det første 16 000 tdw tankskipet ble strukket, til 162 000 tdw Berge Fister i 1970, var det klart at denne epoken Vinter-OL pågikk samtidig. Lønnsomheten ved pro - gikk mot slutten. Egentlig begynte det å skrante allerede i sjektene ble neppe bedre ved det. De norske gullmedaljene 1964. Verftet fikk da kontrakt på å bygge to palleskip for i Innsbruck til Knut Johannesen, Toralf Engan og Tormod Det Stavangerske Dampskibsselskab: M/S Rogaland og Knutsen kostet Sigvald Bergesen dyrt. M/S Akershus. Det genererte nok ikke noe overskudd, men medvirket til å holde beskjeftigelsen oppe. De to IKKE RADIKALT Å VÆRE MOT OLJE DEN GANG småtassene ble forøvrig bygget ved siden av hverandre på Selv om det ut hele 1960-tallet ble bygget tankskip både 7. -

Income Development in Norwegian Municipalities

Income Development in Norwegian Municipalities A Descriptive Analysis of 16 Norwegian Municipalities Over 150 Years Jeanette Strøm Fjære MASTER THESIS AT THE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY OF OSLO JANUARY 2014 i ii Income Development in Norwegian Municipalities A Descriptive Analysis of 16 Norwegian Municipalities Over 150 Years iii © Jeanette Strøm Fjære 2014 Income Development in Norwegian Municipalities Jeanette Strøm Fjære http://www.duo.uio.no Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo iv Abstract More than 60 years ago Simon Kuznets found an empirical relationship between inequal- ity and economic growth, which developed into the well-known inverted U hypothesis, first published in 1950. This thesis describes the development in 16 municipalities focusing on five variables, in re- lation to Kuznets inverted U hypothesis. These are population growth, industry structure, mean income, income inequality and poverty. The Norwegian economy has developed from a preindustrial economy with few cities and a small government sector to an economy based on modern service industries, large and populated cities and a sizable government sector. Mean income has increased, and the poverty rate has declined. In addition, this thesis suggest that income inequality declined until the beginning of the 1990s, but after this the trend has been increasing. This gives a relationship between income inequality and economic growth that is more similar to an actual U than the inverted U found by Kuznets. The recent increase in income inequality is likely to be related to a deregulation of financial markets in 1984 and reduced taxes on capital income in 1992. In addition, 1992 was the end of the Norwegian banking crisis, and a turning point in the Norwegian business cycles, after an economic downturn during the previous years. -

The Agrarian Life of the North 2000 Bc–Ad 1000 Studies in Rural Settlement and Farming in Norway

The Agrarian Life of the North 2000 bc–ad 1000 Studies in Rural Settlement and Farming in Norway Frode Iversen & Håkan Petersson Eds. THE AGRARIAN LIFE OF THE NORTH 2000 BC –AD 1000 Studies in rural settlement and farming in Norway Frode Iversen & Håkan Petersson (Eds.) © Frode Iversen and Håkan Petersson, 2017 ISBN: 978-82-8314-099-6 This work is protected under the provisions of the Norwegian Copyright Act (Act No. 2 of May 12, 1961, relating to Copyright in Literary, Scientific and Artistic Works) and published Open Access under the terms of a Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). This license allows third parties to freely copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as well as remix, transform or build upon the material for any purpose, including commercial purposes, provided the work is properly attributed to the author(s), including a link to the license, and any changes that may have been made are thoroughly indicated. The attribution can be provided in any reasonable manner, however, in no way that suggests the author(s) or the publisher endorses the third party or the third party’s use of the work. Third parties are prohibited from applying legal terms or technological measures that restrict others from doing anything permitted under the terms of the license. Note that the license may not provide all of the permissions necessary for an intended reuse; other rights, for example publicity, privacy, or moral rights, may limit third party use of the material. -

The Evolution of Regional Income Inequality and Social Welfare in Norway: 1875-2015

The Evolution of Regional Income Inequality and Social Welfare in Norway: 1875-2015 Jarle Kvile Master of Philosophy in Economics Department of Economics UNIVERSITY OF OSLO December 2017 c Jarle Kvile 2017 The evolution of Regional Income Inequality and Social Welfare in Norway: 1875-2015 Jarle Kvile http://www.duo.uio.no/ Printed: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo Abstract This thesis describes the regional development of social welfare and income inequality in Norway from 1875 to 2015 with an urban/rural divide. It is a descriptive analysis that combines theory of economic development with estimates of inequality. Focusing on five measures; the Gini coefficient, the mean income, social welfare, poverty, and affluence. Kuznets famous inverted U-hypothesis from 1955, describes a relationship between regional inequality and economic growth. The theory has been the basis for much research, and in many countries, regional income inequality has followed the inverted U-pattern. By contrast, Norway does not exhibit a inverted U-pattern. The regional inequality declined from 1875 to 1980, and increased after 1980. Since 1875, Norway’s economy has developed from a pre-industrial economy to a modernized economy with a significant welfare state. Social welfare and mean income have increased, while the poverty rate has declined. This thesis demonstrates that the mean income, income inequality and social welfare have converged between regions from 1875 to 1980. After 1980, however, income inequality and the mean income have diverged, while social welfare has continued to converge. Before the Second World War, the convergence in social welfare between regions was mainly driven by a decline in inequality above the median in the regions with relative high inequality. -

Kulturscena I Hå Vårprogram 2019 Januar Januar

På terskelen til morgonhuset KULTURSCENA I HÅ VÅRPROGRAM 2019 JANUAR JANUAR Laurdag 19. januar kl. 11.00-13.00. Torsdag 24. januar kl. 18.00. Biblioteket på Nærbø Biblioteket på Nærbø «DIAGNOSE: FLINK PIKE» KLESBYTEDAG Føredrag ved Unn Therese Omdal som fortel si Skal du rydde i klesskåpet eller har fine plagg du personlege reise frå å vere utbrent til ein kvardag ikkje bruker sjølv? På den store klesbytedagen kan med mindre stress, meir energi og auka livskvalitet. du få byte dei inn. Føredraget er ei blanding av historieforteljing og Kleda du leverer inn må vere heile, reine, fint konkrete verktøy innan mindfulness og stress- brukt og ikkje utvaska. Undertøy, sokkar, badetøy meistring. og nattøy kan ikkje leverast inn. Innlevering ved Kaffi/te/twist. Gratis. Støtta av Fritt Ord. biblioteket på Nærbø i veke 3, frå og med måndag 14. januar, til og med fredag 18. januar. Du vekslar inn plagga i bongar. Bongane kan du sjølv bruke på den store klesbytedagen. Laurdagen vert rein bytedag. Velkommen! Laurdag 26. januar kl. 11.00-13.00. Biblioteket på Nærbø OPEN SYVERKSTAD Velkommen til biblioteket på open syverk- Tysdag 22. januar kl. 12.30-14.00. Biblioteket på Nærbø stad. Me har symaskin, overlockmaskin MELLOM NÆRBØ og coverstitch-maskin. Ta med deg det du Klubb for deg som går på mellomtrinnet. treng av materiale til ditt eige syprosjekt, Her kan du blant anna prøve deg på 3D-printing, og prøv ut utstyret vårt. Ta gjerne med eigne vinylkutting og å sy på symaskin. Ta med eigen maskinar om du ønskjer. Det vil vere mogleg berbar pc/chromebook + mus om du vil designe å få rettleiing ved bruk av overlock- og 3D-print.