25 Depositional Traditions in Iron Age Kormt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Day Will Come Heidi Moe Graviet Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected]

Criterion: A Journal of Literary Criticism Volume 11 Article 7 Issue 2 Fall 2018 December 2018 Our Day Will Come Heidi Moe Graviet Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/criterion Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Graviet, Heidi Moe (2018) "Our Day Will Come," Criterion: A Journal of Literary Criticism: Vol. 11 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/criterion/vol11/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Criterion: A Journal of Literary Criticism by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “our day will come” Echoes of Nationalism in Seamus Heaney’s “Bogland” Moe Graviet On 5 October 1968, a civil rights march ended in bloodshed in the streets of Londonderry. This event sparked the begin- ning of the Irish “Troubles”—a civil conflict between Protestants loyal to British reign and nationalist Catholics that would span nearly thirty years. Seamus Heaney, an Irish poet living through the turbulent period, saw many parallels between the disturbing violence of the “Troubles” and the tribal violence of the Iron Age, exploring many of these tensions in his poetry. Poems such as “Tollund Man” and “Punishment” still seem to catch attention for their graphic—verging on obsessive—rendering of tribal vio- lence and exploration of age-old, controversial questions concerning civility and barbarism. Poetry became Heaney’s literary outlet for frustration as he struggled to come to terms with the plight of his nation. -

Sports Manager

Stavanger Svømme Club and Madla Svømmeklubb were merged into one swimming club on the 18th of April 2018. The new club, now called Stavanger Svømmeklubb, is today Norway's largest swimming club with 4000 members. The club that was first founded in 1910 has a long and proud history of strong traditions, defined values and solid economy. We are among the best clubs in Norway with participants in international championships (Olympics, World and European Championships). The club give children, youngsters, adults and people with disabilities the opportunity to learn, train, compete and develop in a safe, healthy and inclusive environment. The club has a general manager, an office administrator, a swimming school manager, 7 full-time coaches, as well as a number of group trainers and swimming instructors. The main goal for Stavanger Svømmeklubb is that we want be the preferred swimming club in Rogaland County and a swimming club where the best swimmers want to be. Norway's largest swimming club is seeking a Sports Manager Stavanger Svømmeklubb is seeking an experienced, competent and committed sports manager for a full time position that can broaden, develop and strengthen the club's position as one of the best swimming clubs in Norway. The club's sports manager will be responsible for coordinating, leading and implementing the sporting activity of the club, as well as having the professional responsibility and follow-up of the club's coaches. The sports manager should have knowledge of Norwegian swimming in terms of structure, culture and training philosophy. The job involves close cooperation with other members of the sports committee, general manager and coaches to develop the club. -

Generation of Two New Radiocarbon Standards for Compound-Specific

Radiocarbon, Vol 63, Nr 3, 2021, p 771–783 DOI:10.1017/RDC.2021.15 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press for the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. GENERATION OF TWO NEW RADIOCARBON STANDARDS FOR COMPOUND-SPECIFIC RADIOCARBON ANALYSES OF FATTY ACIDS FROM BOG BUTTER FINDS Emmanuelle Casanova1 • Timothy D J Knowles1,2 • Isabella Mulhall3 • Maeve Sikora3 • Jessica Smyth4 • Richard P Evershed1,2* 1Organic Geochemistry Unit, School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, Cantock’s Close, BS8 1TS, Bristol, UK 2Bristol Radiocarbon Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Facility, University of Bristol, 43 Woodland Road, Bristol, UK 3National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland 4School of Archaeology, University College Dublin, Newman Building, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland ABSTRACT. The analysis of processing standards alongside samples for quality assurance in radiocarbon (14C) analyses is critical. Ideally, these standards should be similar both in nature and age to unknown samples. A new compound-specific approach was developed at the University of Bristol for dating pottery vessels using palmitic and stearic fatty acids extracted from within the clay matrix and isolated by preparative capillary gas chromatography. Obtaining suitable potsherds for use as processing standards in such analyses is not feasible, so we suggest that bog butter represents an ideal material for such purposes. We sampled ca. -

Rennesøy Finnøy Bokn Utsira Karmøy Tysvær Haugesund Vindafjord

227227 ValevValevåg Breiborg 336 239239 Ekkje HellandsbygHellandsbygd 236236 Hellandsbygda Utbjoa SaudaSauda 335 Etne Sauda Bratland 226226 Espeland VihovdaVihovda Åbødalen Brekke Sandvikdal Roaldkvam 240240 241241 Kastfosskrys 334 Egne Hjem UtbjoaUtbjoa Saunes 236 Skartland sør EtneEtne en TTråsavikikaaNærsonersone set 225225 Saua Førderde Gard Kvame Berge vest Ølen kirke Ølen Ørland Hytlingetong Gjerdevik ø EiodalenØlen skule den 332 SveioSveio 222222 Ølensvåg 235235 333 st Hamrabø Bråtveit Saudafjor 237237 224224 Øvrevre VatsVats SvandalSvandal MaldalMaldal 223223 Vindafjord SandeidSandeid Ulvevne Øvre Vats Skole Bjordalsveien Sandeid Fjellgardsvatnet Hylen Landa Løland Tengesdal 223 331 Knapphus Hordaland Østbø Hylen Blikrabygd 238238 Sandvik VanvikVanvik 328328 Vindafjord Hylsfjorden Skrunes SuldalseidSuldalseid Skjold 216216 218218 Sandeidfjorden 230230 Suldal NordreNordre VikseVikse Ørnes 228228 RopeidRopeid Isvik SkjoldSkjold Hustoft VikedalVikedal 217217 Slettafjellet Nesheim Vikedal Helganes 228 330330 Vikse kryss VestreVestre Skjoldafjo Eskedalen 221221 Suldalseid SuldalsosenSuldalsosen Haugesund Stølekrossen Førland Åmsoskrysset Åmsosen IlsvIlsvåg Stole Ølmedal Kvaløy Ropeid Skipavåg Sand Suldalsosen rden 230 Byheiene 229229 Roopeid 327 327327 Stakkestad SkipevSkipevåg kryss SandSand Kariås Røvær kai Nesheim Eikanes kryss Lindum Årek 329329 camping 602 VasshusVasshus Røvær 200200 220220 Suldalsl HaugesundHaugesund ågen Haraldshaugen 205205 Kvitanes Grindefjorden NedreNedre VatsVats Vindafjorden Kvamen Haugesund Gard skole -

Iconic Hikes in Fjord Norway Photo: Helge Sunde Helge Photo

HIMAKÅNÅ PREIKESTOLEN LANGFOSS PHOTO: TERJE RAKKE TERJE PHOTO: DIFFERENT SPECTACULAR UNIQUE TROLLTUNGA ICONIC HIKES IN FJORD NORWAY PHOTO: HELGE SUNDE HELGE PHOTO: KJERAG TROLLPIKKEN Strandvik TROLLTUNGA Sundal Tyssedal Storebø Ænes 49 Gjerdmundshamn Odda TROLLTUNGA E39 Våge Ølve Bekkjarvik - A TOUGH CHALLENGE Tysnesøy Våge Rosendal 13 10-12 HOURS RETURN Onarheim 48 Skare 28 KILOMETERS (14 KM ONE WAY) / 1,200 METER ASCENT 49 E134 PHOTO: OUTDOORLIFENORWAY.COM PHOTO: DIFFICULTY LEVEL BLACK (EXPERT) Fitjar E134 Husnes Fjæra Trolltunga is one of the most spectacular scenic cliffs in Norway. It is situated in the high mountains, hovering 700 metres above lake Ringe- ICONIC Sunde LANGFOSS Håra dalsvatnet. The hike and the views are breathtaking. The hike is usually Rubbestadneset Åkrafjorden possible to do from mid-June until mid-September. It is a long and Leirvik demanding hike. Consider carefully whether you are in good enough shape Åkra HIKES Bremnes E39 and have the right equipment before setting out. Prepare well and be a LANGFOSS responsible and safe hiker. If you are inexperienced with challenging IN FJORD Skånevik mountain hikes, you should consider to join a guided tour to Trolltunga. Moster Hellandsbygd - A THRILLING WARNING – do not try to hike to Trolltunga in wintertime by your own. NORWAY Etne Sauda 520 WATERFALL Svandal E134 3 HOURS RETURN PHOTO: ESPEN MILLS Ølen Langevåg E39 3,5 KILOMETERS / ALTITUDE 640 METERS Vikebygd DIFFICULTY LEVEL RED (DEMANDING) 520 Sveio The sheer force of the 612-metre-high Langfossen waterfall in Vikedal Åkrafjorden is spellbinding. No wonder that the CNN has listed this 46 Suldalsosen E134 Nedre Vats Sand quintessential Norwegian waterfall as one of the ten most beautiful in the world. -

210 Buss Rutetabell & Linjerutekart

210 buss rutetabell & linjekart 210 Skudeneshavn kai - Haugesund bussterminal Vis I Nettsidemodus 210 buss Linjen Skudeneshavn kai - Haugesund bussterminal har 2 ruter. For vanlige ukedager, er operasjonstidene deres 1 Haugesund Via Veavågen Og Koperv 05:24 - 22:54 2 Skudeneshavn Via Kopervik Og Vea 06:25 - 23:25 Bruk Moovitappen for å ƒnne nærmeste 210 buss stasjon i nærheten av deg og ƒnn ut når neste 210 buss ankommer. Retning: Haugesund Via Veavågen Og Koperv 210 buss Rutetabell 87 stopp Haugesund Via Veavågen Og Koperv Rutetidtabell VIS LINJERUTETABELL mandag 05:24 - 22:54 tirsdag 05:24 - 22:54 Skudeneshavn Kai Kaigata 98, Skudeneshamn onsdag 05:24 - 22:54 Skudeneshavn torsdag 05:24 - 22:54 Skolefjellet 2, Skudeneshamn fredag 05:24 - 22:54 Nessagadå lørdag 07:54 - 22:54 Postvegen 64, Skudeneshamn søndag 11:54 - 22:54 Breidablikk Vektarvegen 1, Skudeneshamn Syrevegen 210 buss Info Risdal Retning: Haugesund Via Veavågen Og Koperv Stopp: 87 Kirkeleite Reisevarighet: 110 min Linjeoppsummering: Skudeneshavn Kai, Sandve Sør Skudeneshavn, Nessagadå, Breidablikk, Syrevegen, Løkabergvegen 2, Norway Risdal, Kirkeleite, Sandve Sør, Sandve Nord, Lyng, Vikra, Haga, Sandhåland Sør, Sandhåland Nord, Sandve Nord Dyrland, Kvilhaug, Langåker Sør, Langåker Nord, Vestre Karmøyveg 817, Norway Stol, Stava, Liknes, Ådland, Medhaug, Åkrehamn, Åkrakrossen, Coop Åkrehamn, Tjøsvoll, Lyng Sævelandsvik, Hansadalen, Solheim, Hapaløk, Lyngbakken 2, Norway Munkajord, Vedavågen Kirke, Veavågen, Vedavågen Kirke, Båshus, Slettavegen, Veamyr, Bleikmyrvegen, Vikra Brekke, -

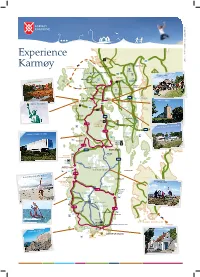

Experience Karmøy

E39 E134 Experience BUS SERVICE TO E134 VANDVIK ØRJAN B. IVERSEN, CAMILLA APPEX.NO / PHOTOS: OSLO, BERGEN, AKSDAL STAVANGER HAUGESUND DYRAFJELLET 172 M.A.S.L Karmøy FAST FERRY: N HAUGESUND - FEØY 20 MIN 9-HOLES HAUSKE GÅRD MINIGOLF 18-HOLES E134 VIKING FARM VISNES MINE AREA KVEITEVIKEN THE FIVE POOR MAIDENS E39 FV47 OLAV’S CHURCH E134 STATUE OF LIBERTY HAUGESUND AIRPORT, E134 KARMØY FV47 HÅVIK HØYEVARDE BUS SERVICE 19 KM K AR TO STAVANGER MØYTUNNELEN AND BERGEN NORDVEGEN HISTORY CENTRE FV47 16 KM Haugalands- KARMØY FISHERY MUSEUM vatnet VEAVÅGEN 12 KM FV47 KOPERVIK ÅKREHAMN COASTAL MUSEUM FV511 ÅKREHAMN 4 KM BEAUTIFUL SILKY BEACHES B SÅLEFJELL PEAK UR MA VE GE BOATHOUSES N AT HOP 8 KM E39 13 KM 8 KM 9-HOLES GREAT SURFING BEACHES FERRY: ARSVÅGEN - MORTAVIKA 20 MIN SKUDENESHAVN JUNGLE PARK STAVANGER HISTORIC SKUDENESHAVN SYRENESET FORT THE MUSEUM IN MÆLANDSGÅRDEN SKUDENESHAVN VIKEHOLMEN GEITUNGEN SIGHTSEEING HIKING AND BIKING TRAILS ACCOMMODATION COMMUNICATIONS Avaldsnes Viking Farm. Follow in the foot- The Karmøy countryside is attractive and diverse Park Inn, Haugesund Airport Hotel Airlines steps of the ancient kings through the historic with many opportunities to get outdoors and Helganesveien 24, 4262 Avaldsnes RyanAir: T: +47 52 85 78 00, www.ryanair.com landscape at Avaldsnes. Bukkøy island features be active or simply relax: T: +47 52 86 10 90 Norwegian: T: +47 815 21 815, www.norwegian.no many reconstructed Viking buildings. Meet www.haugalandet.friskifriluft.no E-mail: [email protected] SAS: T: +47 05400, www.sas.no Vikings for activities and tours in the summer www.parkinnhotell.no/hotell-haugesund Widerøe: T: +47 810 01 200, www.wideroe.no season. -

Food, Economy and Social Complexity in the Bronze Age World

22 Dalia A. Pokutta Food, Economy and Social Complexity in the Bronze Age World FOOD, ECONOMY AND SOCIAL COMPLEXITY IN THE BRONZE AGE WORLD: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY Dalia A. Pokutta1 __________________ 1Archaeological Research Laboratory University of Stockholm, Wallenberglaboratoriet, Lilla Frescativägen 7, 114 18 Stockholm, Sweden, [email protected] Abstract: Despite the fact that greater part of ingredients, such as dairy products or alcoholic drinks, were known al- ready in the Neolithic, food technology of the Bronze Age changed significantly. This paper aims to investigate prehistoric dietary habits and comment on the stable isotope values (13C/15N) of human/faunal remains from several large Bronze Age cemeteries in Europe and beyond. The human skeletal material derives from Early Bronze Age Iberia (2300–2000 BC), mainland Greece (Late Helladic Period III), Bronze Age Transcaucasia (the Kura-Araxes culture 3400–2000 BC), steppes of Kazakhstan (1800 BC), and Early Bronze Age China in Shang period (1523–1046 BC). The aim of this study is to determine distinctive features of food practice in the Bronze Age with an overview of economy and consumer be- haviours in relation to religion and state formation processes. Keywords: Bronze Age, prehistoric diet, isotopic analyses, Spain, Greece, Caucasus, Kazakhstan, China. Abstrakt: Jedlo, hospodárstvo a spoločenská komplexita v svete doby bronzovej. Napriek skutočnosti, že väčšia časť potravín, ako napríklad mliečne výrobky či alkoholické nápoje, bola známa už v závere neolitu, potravinová techno- lógia doby bronzovej sa výrazne zmenila. Táto štúdia skúma praveké stravovacie návyky a vyjadruje sa k hodnotám stabil- ných izotopov (13C/15N) v ľudských/zvieracích pozostatkoch z niekoľkých veľkých pohrebísk z doby bronzovej v Európe aj mimo nej. -

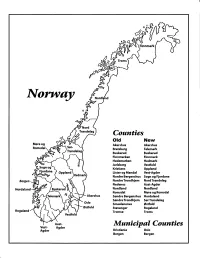

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

New Datings of Three Courtyard Sites in Rogaland

Frode Iversen 26 Emerging Kingship in the 8th Century? New Datings of three Courtyard Sites in Rogaland The Norwegian ‘courtyard sites’ have variously been interpreted as special cultic, juridical, or military assembly sites, which served at more than the purely local level. Previously, on the basis of studies of artefacts and finds of pottery from these structures, the principal period of use of the courtyard sites in Rogaland has been dated to the early and late Roman Iron Age (AD 1–400) and the Migration Period (AD 400–550) through c. AD 600. To test the validity of this date range, the Avaldsnes Royal Manor Project has commissioned thirty new radiocarbon datings of material from three courtyard sites in Rogaland that Jan Petersen had excavated in 1938–50. These are Øygarden, Leksaren, and Klauhaugane; the latter is one of the largest courtyard sites in Norway. Øygarden has not previously been radiocarbon dated. For Klauhaugene, only a few radiocarbon dates had been obtained prior to this study. Leksaren was radiocarbon dated in the 1990s, with the results rather surprisingly indicating that its use continued into the 7th century. The present study demonstrates that the three investigated sites were in use during the Merovingian Period (AD 550–800) – a finding that both confirms and develops previous chronological frameworks. The courtyard sites in Rogaland fell out of use earlier than in other areas along the western coast of Norway. It is therefore suggested that their abandonment was connected to the emergence in the 8th century of royal power accompanied by greater control over jurisdiction – a royal power that subsequently expanded within the coastal zone. -

ROGALAND 23. JULY – 4. AUGUST 2014 Sunday the 27Th We Traveled

ROGALAND 23. JULY – 4. AUGUST 2014 Sunday the 27th we traveled to Karmøy. We drove Here we have parked. through the new tunnel in the triangular connection to Skudesneshavn. We stopped at Skudenes Camping. We parked at this place. The following day, Sunday the 28th, we took a trip down to Skudesneshavn. Those who live here can park their boat right outside Here we are at Kanalen. their door. View across the strait to Vaholmen. Terraces with moored boats. View south towards the bridge that goes over to Skudenes Mekaniske Verksted was built in 1916. Here Steiningsholmen. were the Skude engines produced. I the end of the house is written the name on the wall. Here we come to the square located down by the harbor. Skudeneshavn is a town and a former municipality in Karmøy municipality in Rogaland. Skudesneshavn had 3,327 inhabitants as of 1 January 2013, and is located on Skudeneset on the southern tip of the island Karmøy. Skudesneshavn grew up in the late Middle Ages and the urban society grew rapidly during the herring fishery in the 1800s.Today, the city has modern shipbuilding industry and one of the largest offshore shipping. Solstad Offshore has one of the world's most advanced offshore fleets in service throughout the world. The well-preserved wooden buildings along the harbor, Søragadå, has become one of the region's most visited tourist destination. The flounder fisherman The lobster fisherman The statues in Nordmand valley, Denmark In Nordmandsdalen in Fredensborg Palace Gardens stand 60 statues from various parts of Norway. -

Revheim KLIMAANALYSE Plan 2424

MADLA - REVHEIM KLIMAANALYSE Plan 2424. Områdeplan for Madla - Revheim 14.05.2012 Konsulent: ASPLAN VIAK AS 1 1 DOKUMENTINFORMASJON Oppdragsgiver: Stavanger Kommune Rapporttittel: Klimaanalyse for plan 2424 Madla - Revheim Utgave/dato: 2 / 2012-05-14 Arkivreferanse: - Lagringsnavn rapport Oppdrag: 529216 – Lokalklimaanalyse for Madla-Revheim, Stavanger Oppdragsbeskrivelse: (Basert på tilbud 011763): Lokalklimaanalyse som grunnlag for arkitektkonkurranse Oppdragsleder: Rieck Nina Fag: Arkitektur;Landskap;Plan Tema Bolig;By- og tettstedsutvikling Leveranse: Analyse Skrevet av: Nina Rieck og Kjersti Tau Strand Kvalitetskontroll: Hanne C. Jonassen Asplan Viak AS www.asplanviak.no Stavanger Kommune Asplan Viak AS 2 FORORD I forbindelse med det pågående arbeidet med utarbeidelse av områdeplan for Madla- Revheim (plan 2424), er det utført en lokalklimavurdering på oppdrag for Stavanger kommune ved kultur og byutvikling. Madla-Revheim skal utvikles til en fremtidsrettet og klimavennlig bydel optimalt tilpasset landskapet, tilgrensende jordbruksvirksomhet og beliggenheten i det regionale bysystemet. Lokalklimavurderingen redegjør for de lokalklimatiske forholdene på Madla-Revheim, hvordan lokalklimaet vil kunne bli endret og påvirke planområdet, og hva som bør tas hensyn til i den videre planleggingen. Analysen vil også gi anbefalinger om hvilke områder som er egnet/mindre egnet til utbygging, og hvilke prinsipper og strukturer som bør legges til grunn i de ulike områdene. Det er ikke utført meteorologiske målinger i planområdet. Modelldata fra vindkart for Norge er benyttet for å beskrive vind- og inversjonsforholdene på Madla-Revheim. Analysen er gjennomført i samarbeid mellom Asplan Viak ved Nina Rieck (oppdragsleder) og Kjersti Tau Strand og Kjeller Vindteknikk ved David Edward Weir. Tor Nestande (Asplan Viak) har hatt ansvar for kart- og tegningsproduksjon.