Four Millennia of Dairy Surplus and Deposition Revealed Through

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Day Will Come Heidi Moe Graviet Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected]

Criterion: A Journal of Literary Criticism Volume 11 Article 7 Issue 2 Fall 2018 December 2018 Our Day Will Come Heidi Moe Graviet Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/criterion Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Graviet, Heidi Moe (2018) "Our Day Will Come," Criterion: A Journal of Literary Criticism: Vol. 11 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/criterion/vol11/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Criterion: A Journal of Literary Criticism by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “our day will come” Echoes of Nationalism in Seamus Heaney’s “Bogland” Moe Graviet On 5 October 1968, a civil rights march ended in bloodshed in the streets of Londonderry. This event sparked the begin- ning of the Irish “Troubles”—a civil conflict between Protestants loyal to British reign and nationalist Catholics that would span nearly thirty years. Seamus Heaney, an Irish poet living through the turbulent period, saw many parallels between the disturbing violence of the “Troubles” and the tribal violence of the Iron Age, exploring many of these tensions in his poetry. Poems such as “Tollund Man” and “Punishment” still seem to catch attention for their graphic—verging on obsessive—rendering of tribal vio- lence and exploration of age-old, controversial questions concerning civility and barbarism. Poetry became Heaney’s literary outlet for frustration as he struggled to come to terms with the plight of his nation. -

Climate Change and the Historic Environment

The Archaeologist Issue 108 Autumn 2019 In this issue: Climate change and the From problem to Value, sustainability Jobs in British historic environment: opportunity: responses and heritage impact Archaeology 2015–18 a summary of national to coastal erosion in p24 p27 policies Scotland p3 p14 Study part-time at Oxford Day and Weekend Events in Archaeology One and two day classes on a single topic taught by lecturers and speakers who are noted authorities in their field of research. Courses and Workshops in the Historic Environment Short practical courses providing training in key skills for archaeologists and specialists in historic buildings and the built environment. Part-time Oxford Qualifications Part-time courses that specialise in archaeology, landscape archaeology and British archaeology. Programmes range from undergraduate award courses through to postgraduate degrees. www.conted.ox.ac.uk/arc2019 @OxfordConted SUMO Over 30 years at the forefront of geophysics for archaeology & The perfect balance engineering of theoretical and practical application SUMO Geophysics is the largest really does help with provider of archaeological understanding! Suzi Pendlebury geophysics in the UK. Mortars for Repair and Conservation EXPAND YOUR Recognised by SKILL SET WITH TRAINING IN BUILT HERITAGE CONSERVATION Building Conservation Masterclasses: NO MORE GUESSWORK ABOVE OR BELOW GROUND Learn from leading practitioners Network with participants and specialists 01274 835016 Bursaries available sumoservices.com www.westdean.ac.uk/bcm West Dean College of Arts and Conservation, [email protected] Chichester, West Sussex, PO18 0QZ Autumn 2019 Issue 108 Contents Notes for contributors 2 Editorial Themes and deadlines TA 109 Osteology/Forensic Archaeology: The HS2 3 Climate change and the historic environment: a summary of national policies Louise excavations at St James’ garden Euston has Barker, Andrew Davidson, Mairi Davies and Hannah Fluck highlighted the opportunities and issues that working with human remains brings. -

Generation of Two New Radiocarbon Standards for Compound-Specific

Radiocarbon, Vol 63, Nr 3, 2021, p 771–783 DOI:10.1017/RDC.2021.15 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press for the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. GENERATION OF TWO NEW RADIOCARBON STANDARDS FOR COMPOUND-SPECIFIC RADIOCARBON ANALYSES OF FATTY ACIDS FROM BOG BUTTER FINDS Emmanuelle Casanova1 • Timothy D J Knowles1,2 • Isabella Mulhall3 • Maeve Sikora3 • Jessica Smyth4 • Richard P Evershed1,2* 1Organic Geochemistry Unit, School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, Cantock’s Close, BS8 1TS, Bristol, UK 2Bristol Radiocarbon Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Facility, University of Bristol, 43 Woodland Road, Bristol, UK 3National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland 4School of Archaeology, University College Dublin, Newman Building, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland ABSTRACT. The analysis of processing standards alongside samples for quality assurance in radiocarbon (14C) analyses is critical. Ideally, these standards should be similar both in nature and age to unknown samples. A new compound-specific approach was developed at the University of Bristol for dating pottery vessels using palmitic and stearic fatty acids extracted from within the clay matrix and isolated by preparative capillary gas chromatography. Obtaining suitable potsherds for use as processing standards in such analyses is not feasible, so we suggest that bog butter represents an ideal material for such purposes. We sampled ca. -

Food, Economy and Social Complexity in the Bronze Age World

22 Dalia A. Pokutta Food, Economy and Social Complexity in the Bronze Age World FOOD, ECONOMY AND SOCIAL COMPLEXITY IN THE BRONZE AGE WORLD: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY Dalia A. Pokutta1 __________________ 1Archaeological Research Laboratory University of Stockholm, Wallenberglaboratoriet, Lilla Frescativägen 7, 114 18 Stockholm, Sweden, [email protected] Abstract: Despite the fact that greater part of ingredients, such as dairy products or alcoholic drinks, were known al- ready in the Neolithic, food technology of the Bronze Age changed significantly. This paper aims to investigate prehistoric dietary habits and comment on the stable isotope values (13C/15N) of human/faunal remains from several large Bronze Age cemeteries in Europe and beyond. The human skeletal material derives from Early Bronze Age Iberia (2300–2000 BC), mainland Greece (Late Helladic Period III), Bronze Age Transcaucasia (the Kura-Araxes culture 3400–2000 BC), steppes of Kazakhstan (1800 BC), and Early Bronze Age China in Shang period (1523–1046 BC). The aim of this study is to determine distinctive features of food practice in the Bronze Age with an overview of economy and consumer be- haviours in relation to religion and state formation processes. Keywords: Bronze Age, prehistoric diet, isotopic analyses, Spain, Greece, Caucasus, Kazakhstan, China. Abstrakt: Jedlo, hospodárstvo a spoločenská komplexita v svete doby bronzovej. Napriek skutočnosti, že väčšia časť potravín, ako napríklad mliečne výrobky či alkoholické nápoje, bola známa už v závere neolitu, potravinová techno- lógia doby bronzovej sa výrazne zmenila. Táto štúdia skúma praveké stravovacie návyky a vyjadruje sa k hodnotám stabil- ných izotopov (13C/15N) v ľudských/zvieracích pozostatkoch z niekoľkých veľkých pohrebísk z doby bronzovej v Európe aj mimo nej. -

The Somerset Levels and Moors Are an Ancient and Wildlife-Rich World Just Waiting to Be Channels Were Cut to Speed the Water to the Sea

Left The ‘Willow Man’ sculpture by Serena de la Hey. At 40ft high, it is thought to be the world’s tallest willow sculpture. SUMMER Right Drainage channels, or ‘rhynes’, criss-cross the ancient watery landscape. Below Willows have been a characteristic feature of the Somerset Levels for around 6000 years, and MAN’S have been harvested for LAND their wood nearly as long. The Somerset Levels and Moors are an ancient and wildlife-rich world just waiting to be channels were cut to speed the water to the sea. In 1831 the first steam-powered explored. Alison Thomas and photographer Kim Sayer are our guides to this remarkable landscape. pumping station swung into action at Westonzoyland. When steam gave way ust outside Bridgwater, a giant hillocks dripping with legend and myth. took up residence, moving down to to diesel in the 1950s, the station fell J Willow Man strides forth beside the Curlews nest, herons fish for eels and the wetlands when the winter floods out of use and it is now a museum M5, inviting travellers to explore the otters hide away in the reedbeds. receded. This is the original Somerset, devoted to the way things were done secret world beyond his outstretched Willows have been a feature of from the Saxon Sumersaeta, meaning in days gone by. arms. Most people scurry on by, this water wonderland since the ‘summer man’s land’. Flooding remains a fact of life, unaware of his significance. Those first settlers moved in 6000 years Since Roman times successive however, and people still live on who know better are richly rewarded. -

Thinking History Activity

www.thinkinghistory.co.uk Notes for Teachers: the site, the finds and additional resources These notes describe the site and the finds and then lists some useful web-links and visual material. The original excavations Glastonbury Lake Village was built on an artificial island in shallow water on the Somerset Levels during the Iron Age. It was discovered by Arthur Bulleid in 1892. Bulleid was a medical student, amateur archaeologist and the son of the founder of the Glastonbury Antiquarian Society. Having read about lake villages in Switzerland, he searched for similar sites in Somerset, leading to his discovery of a number of earth mounds, just north of Glastonbury. From then until 1907, Bulleid and a team of helpers excavated the site. In recent years archaeologists have returned to the site and have re-interpreted Bulleid’s original conclusions. When did people live in the lake village? The dates suggested by archaeologists vary a little but not significantly. The settlement was first used between 250 and 150BC and was home to about 200 people. The occupants were forced to leave in about 50 AD, due to rising water levels caused by deterioration in the climate. This is therefore an Iron Age site. A second debate is about whether the site was occupied continuously or whether there was a break in occupation with the first settlers building square or rectangular houses and the later occupiers building roundhouses. A study of the site by Bryony Orme and John Coles (1980) suggests that as well as the buildings used as homes there were specialised areas and buildings for woodworking, pottery manufacture and working in iron, bronze and bone. -

St. George Gray, H, Excavations at the Glastonbury Lake Village, in July

(JBrcatJattons at tfte ®Ia0tont)urp lake QiHage, in 3|ulp, 1902. BY H. ST. GEOEGE GEAY. ISCOVERIES of prehistoric lacustrine abodes in Eng- land have been of rare occurrence ; but they are com- mon in Scotland, —^Avhere their existence was systematically brought to light in 1857, —and still more so in Ireland, where public attention was first directed to the crannogs by Sir W. Wilde as early as 1839. The discoveries and explorations of Irish crannogs are now, however, almost numberless \ but not so(1)in England. As Dr. Munro^ has recorded, lacustrine re- (2) mains have been discovered in the meres of Norfolk and Suf- folk, at Wretham and Barton,—in the middle of the last cen- tury ; at Crowland and near Ely, in the Fenland; in the Llangorse Lake, near Brecon ; in one or two small sites in Berks, and at some five stations in Holderness, Yorkshire.^ Quite recently attention has been called to supposed lake dwel- . Lake Dwellings of Europe, 1890, pp. 458—474. General Pitt-Rivers (then Colonel Lane-Fox), as early as 1867, brought to the notice of antiquaries that “certain Piles had been found near London Wall and Southwark, possibly the remains of Pile Dwellings.” Roman remains only were found. The General was always most cautious in theorizing and in generalizing; but it would appear from Mr. Edwin Sloper’s letter to the City Press of April 2nd, 1902, that General Pitt-Rivers, with others, mistook stable- stated dung, in its decayed state, for peat ; however, the General markedly that “it is difficult, if not impossible, to reconcile this enormous rise of seven to nine feet of peat during the four centuries of Roman occupation.” Doubt- less, however, the marsh theory was uppermost in his mind. -

Dooley Dispatch

The Dooley Dispatch May 2018 Celebrating 39 years of Friendship, Unity, and Christian Charity Editor – Pat Shea 804.516.9598 ([email protected]) Photographer – Joe McGreal ([email protected]) Webmaster – Patrick Shea ([email protected]) Webpage http://aohrichmond.org Check out the web page for better pictures, events, green pages, various reports Chaplain Next Meeting – Tuesday May 8, 2018 7:00 p.m. St. Paul’s Church Fr. George Zahn President’s Message: President Scott Nugent 503-9888 Brothers, [email protected] Vice President It seems like we went from winter to summer in one Mike Canning 690-0338 week. Welcome to Richmond! [email protected] th Recording Secretary There is no bigger news this month than the 50 Anniversary John Condon 980-5649 of Father George Zahn’s ordination. As we all know, Father [email protected] George is the Chaplin of our Order and is one of the most Financial Secretary dedicated members. How many of us can say that both of John Costello 920-0534 our parents where each in the AOH/LAOH? The actual date [email protected] of his ordination was May 11, 1968. We are celebrating this momentous occasion Treasurer during our May 8 meeting at St Paul’s. Spouses are invited. We will have food, Patrick Knightly 687-3868 drinks and stories about our very own Father George. Please plan on attending. [email protected] Chairman of Standing We had another banner year for raffle tickets. Great job by Jim Woods leading the Committees effort and the Order for selling the tickets. Final numbers will be forthcoming. -

Welcome to Your Cedar Lodge Enjoy Your Stay at Old Oaks

Welcome to your Cedar Lodge Enjoy your stay at Old Oaks General Information New Click & Collect app - download Hopt to your device Wifi Free service Connect to any Old Oaks Free Wi-Fi access point in your phone wifi settings Enter password oldoaks2408 A splash page will appear (if not, open browser and enter www.wifi-login.co.uk) Follow instructions for free access at limited speeds up to 1MB NB You will be required to re-login every time you use the free WIFI Premium service (free for Lodge & Shepherd Hut guests - voucher issued on arrival) Follow steps above and choose Premium (paid) for speeds up to 10MB Choose preferred service and number of devices Follow instructions to pay Enjoy quality, reliable WIFI NB Speeds may vary and are not guaranteed, especially at busy times Security Barriers To ensure the security of the park and our guests, the park gates are locked between 11.30pm and 7.30am. The exit gate can be used at any time, however, entry into the park is not possible during these. Vehicles to be left in the car park and entry on foot. Campfires & BBQs With wood are not permitted. Fire pits with smokeless fuel are fine. Dogs Must be kept on a short lead at all times, unless using the dedicated dog exercise area where dogs can run free. Check out time Please vacate your accommodation by 10am and return your key to the key drop. Noise levels Our guests choose Old Oaks to enjoy the peace and tranquility of the countryside, therefore we ask all guests to keep music, TVs and all noise to a reasonable level at all times and an absolute minimum after 10.30pm. -

Bulleid, A, the Lake Village Near Glastonbury, Part II, Volume 40

I I I—J I I I I I SCALE POUR FEET TO ONE INCH PLAN OF HOUSE IN BRITISH VILLAGE, GLASTONBURY. Cf)e lake Qtliage near ©lastontmrg. BY ARTHUR BULLEID. THE Glastonbury lake village is of the crannog or artifi- cial island type, and consists of between sixty and seventy dwelling mounds : it covers nearly three-and-a-half acres, the east and west and north and south diameters being three hundred and four hundred feet respectively. During the seasons of 1892 and 1893, the time was chiefly taken up with the examination of fifteen dwelling mounds, and of the causeway, and other stone and timber structures in the peat outside the village border. This year has been occu- pied in tracing the village border, which has now been un- covered to the extent of five-hundred-and-fifty feet, or about one third of its total circumference. These investigations have added much valuable information respecting the size and shape of the village, and have established the following facts : a. That the village wr as originally surrounded by the water of a shallow mere. b. That five feet of peat accumulated during the occupation. c. That a strong palisading of post and piles surrounded and protected the village. d. That the ground work of the village near its margin is artificial in some places for the depth of five feet. Before beginning to describe the various structures consti- tuting the village, it will be well to refer first to its situation and the formation of the land near it. -

9 the Role of the Bog in Ethnic Tourism

BOGS OF IRELAND text 11/18/03 2:33 pm Page 53 9 THE ROLE OF THE BOG IN ETHNIC TOURISM. BOGS IN THE IRISH PSYCHE. You can take the man out of the bog but you can’t take the bog out of the man. We, the Irish, are bog people. The bog water runs in our veins. The bog represents our collective unconsciousness. The bog is a symbol of our Irishness. It awakens our ancient race memory of pain and suffering, poverty and famine when we were deprived of everything except the bog. This hurts us deeply and makes us uncomfortable and ashamed. To escape this shame we refer to the bog in derisory terms i.e. "He’s only a bogman". But, painful as the past has been, we cannot forget it. Neither do we want to forget it because our past is part of what we are. To the Irish, the bog is also a very beautiful and benign place. We associate quietness, stillness, reflection and otherness with the bog. The bog represents the mystery inside us. When we go there as children, we go with older people. It is the place where age barriers break down. Games are played, stories are told and songs are sung in spite of the back-breaking work. Grown men light fires and make tea, normally women’s work. The simple bread and butter tastes like heavenly food. We stay there all day and it is usually summer. There is a sense of being in migration. The place is physically beautiful. -

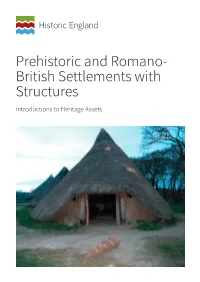

Prehistoric and Romano-British Settlements with Structures

Prehistoric and Romano- British Settlements with Structures Introductions to Heritage Assets Summary Historic England’s Introductions to Heritage Assets (IHAs) are accessible, authoritative, illustrated summaries of what we know about specific types of archaeological site, building, landscape or marine asset. Typically they deal with subjects which have previously lacked such a published summary, either because the literature is dauntingly voluminous, or alternatively where little has been written. Most often it is the latter, and many IHAs bring understanding of site or building types which are neglected or little understood. This IHA provides an introduction to prehistoric and Romano-British settlements with structures. This asset description focuses on a limited number of site types where it is possible to observe different forms of enclosure boundary as well as related structures such as houses and ancillary buildings. The description includes courtyard houses, stone hut circles, unenclosed stone hut circle settlements, as well as wetland settlements (utilising predominantly wooden structures) and their development. A list of in-depth sources on the topic is suggested for further reading. This document has been prepared by Dave Field and edited by Joe Flatman, Pete Herring and David McOmish. It is one of a series of 41 documents. This edition published by Historic England October 2018. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. Please refer to this document as: Historic England 2018 Prehistoric and Romano-British Settlements with Structures: Introductions to Heritage Assets. Swindon. Historic England. HistoricEngland.org.uk/listing/selection-criteria/scheduling-selection/ihas- archaeology/ Front cover Reconstruction of Roundhouse 1 (the “Cook House”), excavated 1981, built on the site of the original structure.