A Historical Ecology of the Bog of Allen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Day Will Come Heidi Moe Graviet Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected]

Criterion: A Journal of Literary Criticism Volume 11 Article 7 Issue 2 Fall 2018 December 2018 Our Day Will Come Heidi Moe Graviet Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/criterion Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Graviet, Heidi Moe (2018) "Our Day Will Come," Criterion: A Journal of Literary Criticism: Vol. 11 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/criterion/vol11/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Criterion: A Journal of Literary Criticism by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “our day will come” Echoes of Nationalism in Seamus Heaney’s “Bogland” Moe Graviet On 5 October 1968, a civil rights march ended in bloodshed in the streets of Londonderry. This event sparked the begin- ning of the Irish “Troubles”—a civil conflict between Protestants loyal to British reign and nationalist Catholics that would span nearly thirty years. Seamus Heaney, an Irish poet living through the turbulent period, saw many parallels between the disturbing violence of the “Troubles” and the tribal violence of the Iron Age, exploring many of these tensions in his poetry. Poems such as “Tollund Man” and “Punishment” still seem to catch attention for their graphic—verging on obsessive—rendering of tribal vio- lence and exploration of age-old, controversial questions concerning civility and barbarism. Poetry became Heaney’s literary outlet for frustration as he struggled to come to terms with the plight of his nation. -

Landscape Character Assessment

OUSE WASHES Landscape Character Assessment Kite aerial photography by Bill Blake Heritage Documentation THE OUSE WASHES CONTENTS 04 Introduction Annexes 05 Context Landscape character areas mapping at 06 Study area 1:25,000 08 Structure of the report Note: this is provided as a separate document 09 ‘Fen islands’ and roddons Evolution of the landscape adjacent to the Ouse Washes 010 Physical influences 020 Human influences 033 Biodiversity 035 Landscape change 040 Guidance for managing landscape change 047 Landscape character The pattern of arable fields, 048 Overview of landscape character types shelterbelts and dykes has a and landscape character areas striking geometry 052 Landscape character areas 053 i Denver 059 ii Nordelph to 10 Mile Bank 067 iii Old Croft River 076 iv. Pymoor 082 v Manea to Langwood Fen 089 vi Fen Isles 098 vii Meadland to Lower Delphs Reeds, wet meadows and wetlands at the Welney 105 viii Ouse Valley Wetlands Wildlife Trust Reserve 116 ix Ouse Washes 03 THE OUSE WASHES INTRODUCTION Introduction Context Sets the scene Objectives Purpose of the study Study area Rationale for the Landscape Partnership area boundary A unique archaeological landscape Structure of the report Kite aerial photography by Bill Blake Heritage Documentation THE OUSE WASHES INTRODUCTION Introduction Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Context Ouse Washes LP boundary Wisbech County boundary This landscape character assessment (LCA) was District boundary A Road commissioned in 2013 by Cambridgeshire ACRE Downham as part of the suite of documents required for B Road Market a Landscape Partnership (LP) Heritage Lottery Railway Nordelph Fund bid entitled ‘Ouse Washes: The Heart of River Denver the Fens.’ However, it is intended to be a stand- Water bodies alone report which describes the distinctive March Hilgay character of this part of the Fen Basin that Lincolnshire Whittlesea contains the Ouse Washes and supports the South Holland District Welney positive management of the area. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS)

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 7, 2nd edition, as amended by COP9 Resolution IX.1 Annex B). A 3rd edition of the Handbook, incorporating these amendments, is in preparation and will be available in 2006. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House City Road Designation date Site Reference Number Peterborough Cambridgeshire PE1 1JY UK Telephone/Fax: +44 (0)1733 – 562 626 / +44 (0)1733 – 555 948 Email: [email protected] 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: Designated: 28 November 1985 3. Country: UK (England) 4. Name of the Ramsar site: Martin Mere 5. -

Lullymore Island Kildare Irish Peatland Conservation Council Map and Guide Comhairle Chaomhnaithe Phortaigh Na Héireann

Lullymore Island Kildare Irish Peatland Conservation Council Map and Guide Comhairle Chaomhnaithe Phortaigh na hÉireann Island in the Bog Lullymore is a mineral soil island completely surrounded by the Bog of Allen in Co. Kildare. The Island is 93m above sea level and covers an area of 220ha. The population of Lullymore Island is around 150 people in 50 houses. Lullymore Island is located on the R414 between the towns of Rathangan and Allenwood in Co. Kildare. The Island has its own early Christian Monastic Settlement, a rich mosaic of wildlife and a vibrant communty of residents. Air photograph of Lullymore Island in Co. Kildare outlined in yellow. The process of reclaiming Lullymore Bog to farmland is underway along the north-west flank of the island. On all other sides the bog is being milled for peat and used to generate electricity. The route of the Lullymore Loop Walk in shown in orange and blue. Photo: Jim Ryan, National Parks and Wildlife Service, modified by Leoine Tijsma Lullymore Bog - A Changing Story From the left: Lullymore Briquettes, Allenwood Power Station, Industrial peat extraction, Lodge Bog Nature Reserve and wetland habitat creation following completion of peat extraction. Lullymore bog with an area of 6,575ha was the largest bog in the complex of bogs known as the Bog of Allen and it gives its name to the Island of Lullymore. Lullymore Bog was first developed commercially by entrepreneurs in the 19th century and to this day it continues to provide milled peat which is burned to generate electricity in the Clonbollogue Power Station in Co. -

Global Peatland Restoration Manual

Global Peatland Restoration Manual Martin Schumann & Hans Joosten Version April 18, 2008 Comments, additions, and ideas are very welcome to: [email protected] [email protected] Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, Greifswald University, Germany Introduction The following document presents a science based and practical guide to peatland restoration for policy makers and site managers. The work has relevance to all peatlands of the world but focuses on the four core regions of the UNEP-GEF project “Integrated Management of Peatlands for Biodiversity and Climate Change”: Indonesia, China, Western Siberia, and Europe. Chapter 1 “Characteristics, distribution, and types of peatlands” provides basic information on the characteristics, the distribution, and the most important types of mires and peatlands. Chapter 2 “Functions & impacts of damage” explains peatland functions and values. The impact of different forms of damage on these functions is explained and the possibilities of their restoration are reviewed. Chapter 3 “Planning for restoration” guides users through the process of objective setting. It gives assistance in questions of strategic and site management planning. Chapter 4 “Standard management approaches” describes techniques for practical peatland restoration that suit individual needs. Unless otherwise indicated, all statements are referenced in the IPS/IMCG book on Wise Use of Mires and Peatlands (Joosten & Clarke 2002), that is available under http://www.imcg.net/docum/wise.htm Contents 1 Characteristics, -

The Virginia Wetlands Report Vol. 12, No. 2

W&M ScholarWorks Center for Coastal Resources Management Virginia Wetlands Reports (CCRM) Summer 7-1-1997 The Virginia Wetlands Report Vol. 12, No. 2 Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/ccrmvawetlandreport Part of the Environmental Education Commons Recommended Citation Virginia Institute of Marine Science, "The Virginia Wetlands Report Vol. 12, No. 2" (1997). Virginia Wetlands Reports. 28. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/ccrmvawetlandreport/28 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Coastal Resources Management (CCRM) at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Virginia Wetlands Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Summer 1997 TheThe VirginiaVirginia Vol. 12, No. 2 WetlandsWetlands ReportReport Wetlands Mitigation Banks: Creating Big Wetlands to Compensate for Many Small Losses Carl Hershner etlands mitigation banking is a acres each year. When you realize that wetland if at all possible. Relocating relatively new tool for wetlands new tidal wetlands are not appearing development on a parcel of land, or managers.W It is finding increasing naturally at a rate anywhere close to redesigning a project can often pre- application in the struggle to achieve a the rate of loss caused by man and serve the existing resource. When “no net loss” goal for our remaining nature, this “preventable” loss becomes avoidance is not possible, minimizing wetland resources. The concept of a concern. the area of impact is always the second creating wetlands and thus establish- The problem confronting resource objective. -

Generation of Two New Radiocarbon Standards for Compound-Specific

Radiocarbon, Vol 63, Nr 3, 2021, p 771–783 DOI:10.1017/RDC.2021.15 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press for the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. GENERATION OF TWO NEW RADIOCARBON STANDARDS FOR COMPOUND-SPECIFIC RADIOCARBON ANALYSES OF FATTY ACIDS FROM BOG BUTTER FINDS Emmanuelle Casanova1 • Timothy D J Knowles1,2 • Isabella Mulhall3 • Maeve Sikora3 • Jessica Smyth4 • Richard P Evershed1,2* 1Organic Geochemistry Unit, School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, Cantock’s Close, BS8 1TS, Bristol, UK 2Bristol Radiocarbon Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Facility, University of Bristol, 43 Woodland Road, Bristol, UK 3National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland 4School of Archaeology, University College Dublin, Newman Building, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland ABSTRACT. The analysis of processing standards alongside samples for quality assurance in radiocarbon (14C) analyses is critical. Ideally, these standards should be similar both in nature and age to unknown samples. A new compound-specific approach was developed at the University of Bristol for dating pottery vessels using palmitic and stearic fatty acids extracted from within the clay matrix and isolated by preparative capillary gas chromatography. Obtaining suitable potsherds for use as processing standards in such analyses is not feasible, so we suggest that bog butter represents an ideal material for such purposes. We sampled ca. -

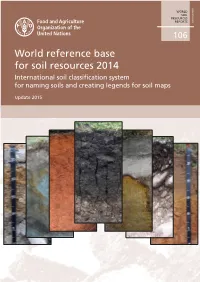

World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014 International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps

ISSN 0532-0488 WORLD SOIL RESOURCES REPORTS 106 World reference base for soil resources 2014 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps Update 2015 Cover photographs (left to right): Ekranic Technosol – Austria (©Erika Michéli) Reductaquic Cryosol – Russia (©Maria Gerasimova) Ferralic Nitisol – Australia (©Ben Harms) Pellic Vertisol – Bulgaria (©Erika Michéli) Albic Podzol – Czech Republic (©Erika Michéli) Hypercalcic Kastanozem – Mexico (©Carlos Cruz Gaistardo) Stagnic Luvisol – South Africa (©Márta Fuchs) Copies of FAO publications can be requested from: SALES AND MARKETING GROUP Information Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Viale delle Terme di Caracalla 00100 Rome, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (+39) 06 57053360 Web site: http://www.fao.org WORLD SOIL World reference base RESOURCES REPORTS for soil resources 2014 106 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps Update 2015 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2015 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

Holme Fen Nature Reserve the Lost Lake and Other

Today, Holme Fen is the largest lowland Once the Mere had been 3 The gamekeeper’s plantation drained, over half the silver birch woodland in England, but it has After the drainage, Holme Fen was not farmed had a very different history. wildlife recorded in the area became extinct here. because it was still too wet and boggy. As it One example was the dried out, Holme Fen turned from reeds to 1 Whittlesea Mere and the Holme Posts Swallowtail butterfly raised bog and then to birch woodland. Swallowtail butterfly. by Matt Berry The ground beneath your feet was once level with 2 Disappearing houses Earlier this century, this area was used for the top of the Holme Posts. At that time, game. In the gamekeeper’s plantation (also One of the most dramatic changes here has been Whittlesea Mere was a short distance away to the know as ‘Ballard’s Covert’) you will see a mix of the drop in ground levels following the drainage, as east. At three miles across, it was a spectacular different trees including oak, birch, and alder. the peat dried out and eroded. Tony Redhead, sight - the largest lake in lowland England. whose family grew up here, remembers some of The variety of trees makes it a good place to You might have come to the effects: hear and see woodland birds, such as Blackcaps, take part in one of the "There was one house, in the 1950s, that had to Woodpeckers and Redpolls. Holme Fen was famous ice skating races be pulled down because you could walk bought for the nation in 1952. -

Turbary Restoration Meets Variable Success: Does Landscape Structure Force Colonization Success of Wetland Plants?

RESEARCH ARTICLE Turbary Restoration Meets Variable Success: Does Landscape Structure Force Colonization Success of Wetland Plants? Boudewijn Beltman,1,2 NancyQ.A.Omtzigt,3 and Jan E. Vermaat3 Abstract of ponds in the complex, the SW orientation of ditches in these complexes and pH, and transparency of the water. Peat ponds have been restored widely in the Netherlands Age of the ponds (1–9 years), area of open water (8–42%), to enhance the available habitat for species-rich plant and shoreline density (13–43 km/km2 in the complex) did communities that characterize the early succession stages not contribute significantly to colonization success. Separa- toward land. Colonization success of 33 target aquatic tion of the effect of a species-rich surrounding landscape, species has been quantified in eight complexes of new the possibility to disperse through that landscape, the spa- ponds. It has been related to the lay-out of these ponds, the tial lay-out of the complex and transparency of the water structure of the surrounding landscape, (historic) preva- were precluded by the strong covariance along the first PC. lence of source populations within the complex and within a Probably all three are independently important. It is spec- perimeter of 10 km, and pond water quality. Colonization ulated that diel migration by waterfowl may be responsible success was variable: between 6 and 26 target species had for the dispersal of plant propagules to the pond complex, reached the complexes in 1998. This success was coupled whereas within-complex dispersal to establishment sites is to the first principal component (PC) in a principal compo- enhanced by wind and water movement. -

National Peatlands Strategy

NATIONAL PEATLANDS STRATEGY 2015 National Parks & Wildlife Service 7 Ely Place, Dublin 2, D02 TW98, Ireland t: +353-1-888 3242 e: [email protected] w: www.npws.ie Main Cover photograph: Derrinea Bog, Co. Roscommon Photographs courtesy of: NPWS, Bord na Móna, Coillte, RPS, Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine, National Library of Ireland, Friends of the Irish Environment and the IPCC. MANAGING IRELAND’S PEATLANDS A National Peatlands Strategy 2015 Roundstone Bog, Co. Galway CONTENTS PART 1 PART 3 1 INTRODUCTION 004 6 IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING 060 1.1 Peatlands in Ireland 005 1.2 Protected Peatlands in Ireland 007 APPENDICES 2 THE CHANGING VIEW APPENDIX 1 OF IRISH PEATLANDS 008 SUMMARY OF PRINCIPLES 2.1 A New Understanding 009 AND ACTIONS 062 2.2 Seeking Balance between Traditional and Hidden Values 009 2.3 Turf cutting controversy – APPENDIX 2 a catalyst for change 011 GLOSSARY 070 2.4 The Way Forward 013 APPENDIX 3 PART 2 EU DIRECTIVES REFERRED TO IN THE STRATEGY 076 3 DEVELOPMENT OF THE STRATEGY 014 APPENDIX 4 4 VISION AND VALUES 018 LINKS & FURTHER INFORMATION 080 5 MANAGING OUR PEATLANDS: PRINCIPLES, POLICIES AND ACTIONS 024 5.1 Overview 024 5.2 Existing Uses 025 5.3 Peatlands and Climate Change 034 5.4 Air Quality 036 5.5 Protected Peatlands Sites 037 5.6 Peatlands outside Protected Sites 045 5.7 Responsible Exploitation 048 5.8 Restoration & Rehabilitation of Non-Designated Sites 050 5.9 Water Quality, Water Framework Directive and Flooding 050 5.10 Public Awareness & Education 055 5.11 Tourism & Recreational Use 058 5.12 Unauthorised Dumping 059 5.13 Research 059 PART 1 004 1. -

Peat Places Peat Today

Rathlin Island Peat places Tievebulliagh Carrick-a-rede The Glens of Antrim contain Garron Plateau many places where peat can The Garron Plateau is the biggest area of This upland area contains shallow peat. be found. The map highlights Knocklayde Ballintoy intact blanket bog on the east coast of Ireland. A rare rock known as porcellanite was peat places to explore. The site is rich with varieties of plants and wildlife. harvested here during the stone age and exported throughout Europe. Garron Plateau has undergone an extensive restoration project. Ballycastle Fairhead Special peat places Access from Cargan village, 10 miles north of Moyle Way Areas of Outstanding Ballymena on the Glenravel Road (A43) and eight Natural Beauty (AONB) miles south of Cushendall. Car parking is available at Dungonnell Dam, near Cargan village. Tow River Carey River Areas of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) Glentasie Ballycastle Ramsar Wetland Sites of international importance Forest Special Protection Areas (SPA) Glenmakeeran River Glenshesk River Glenshesk Slieveanorra & Croaghan Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) Ballypatrick Moyle Way Forest National Nature Reserves (NNR) View from Glenaan Slieveanorra and Croaghan is an important Glenshesk Cregagh area of largely intact blanket bog. Slieveanorra Peat Areas Mountain shows the different stages in the Wood View from Tievebulliagh Armoy Non Peat Areas formation, erosion and regeneration of peat. Breen Cushendun Garron Plateau Ronan's Way AONB boundary line A variety of plants and upland birds can be Wood spotted, as can the common lizard. Main Roads Croaghan Breen Mountain Slieveanorra was the site of the Battle Glendun Forest Walk Glencorp Walking Routes Through Peatland of Orra in 1583.