Landscape Character Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barber's Almanac 1959

Items of Interest during the Year 195758 (taken from Barber's Almanack 1959). Gathered from the Local Newspapers, etc. during the past year. Every care is taken to make the following list correct but no item or date is guarenteed by the publisher. December, 1957. 1Sergeant C. D. Sutton, stationed at Whittlesey, retired from the Isle of Ely Constabulary after 30 years service. Before the war he was stationed at Littleport and was a regular member of the Littleport cricket team. He was promoted to sergeant in 1946. 4Combined Choir concert given by the Littleport Ladies, Male Voice and Children's Choirs at the Grange Convalescent Home. Mrs. C. R. Browning conducted. 621st Annual Christmas dinner and social held at the Transport and General Workers' Union Convalescent Home. It was the final appearance at the dinner of Mr. W. Kennedy, Superintendent, who was retiring in July, 1958. Mr. Herbert Storey, of The Crescent, retired from the office of Senior Beadle of Littleport "Unity and Love" branch of the Ancient Order of Foresters. Aged 83, he joined the Friendly Society in 1890. 7Parish Church Christmas Fair opened by Mrs. Lee Bennett, of Downham Market. Proceeds amounted to £100. 8Memorial service to the late Mr. Victor G. Kidd held at Victoria Street Methodist Church. 11Annual Meeting of Littleport Women's Institute. Spoons for points gained in competitions were awarded to Mesdames J. Law, C. Easy, M. Milne Wilson, B. G. Wright and D. Barber. !!! Meeting of Ely Rural District Council. The Littleport Committee reported that Mr. -

Welcome to Cottenham Community Information

Welcome to Cottenham Community information N IET YT • ZONDER • ARB White layer is grouped - background is just so you can find it! N IET YT • ZONDER • ARB Clubs 4 Welcome to Cottenham Children and family groups 4 Community groups 7 Creative groups 8 Cottenham Parish Council, Musical groups for adults and children 8 with support from South Sport, fitness and health 9 Cambridgeshire District Council, has created this directory of clubs, associations, facilities and Education 14 events to provide residents with Adult learning 14 everything you need to know to be Schools 14 able to fully enjoy being part of the Cottenham community. After school clubs 14 For those who are new to our Parish, we hope you will find the Facilities 15 information in this booklet helpful Bank and shops 15 as you start to get to know the people and Parish of Cottenham. Cemetery and churches 15 We wish a very warm welcome to Health 16 all new residents. Library 16 There are a number of local events Food and drink 17 that are organised throughout the Recreation 18 year – such as the Fun Run in May, the Fen Edge Festival in June (every Vets 18 other year), the Cottenham Feast Parade in October, and Carols on the Green in December. Outdoor and environment 19 Outdoor activities 19 If you would like to keep up to date with such events the Environment group 20 best thing to do is to join our Facebook group (www.facebook. com/cottenhamparishcouncil) Support for our community 20 or check our website regularly Caring for our community 20 (www.cottenhampc.org.uk). -

Peterborough's Green Infrastructure & Biodiversity Supplementary

Peterborough’s Green Infrastructure & Biodiversity Supplementary Planning Document Positive Planning for the Natural Environment Consultation Draft January 2018 297 Preface How to make comments on this Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) We welcome your comments and views on the content of this draft SPD. It is being made available for a xxxx week public consultation. The consultation starts at on XX 2018 and closes on XX xxx 2018. The SPD can be viewed at www.peterborough.gov.uk/LocalPlan.There are several ways that you can comment on the SPD. Comments can be made by email to: [email protected] or by post to: Peterborough Green Infrastructure and Biodiversity Draft SPD Consultation Sustainable Growth Strategy Peterborough City Council Town Hall Bridge Street Peterborough PE1 1HF All responses must be received by XX xxxx 2018. All comments received will be taken into consideration by the council before a final SPD is adopted later in 2018. 2 298 Contents 1 Introduction 4 Purpose, Status, Structure and Content of the SPD 4 Collaborative working 4 Definitions 5 Benefits of GI 5 Who should think about GI & Biodiversity 7 2 Setting the Scene 8 Background to developing the SPD 8 Policy and Legislation 8 3 Peterborough's Approach to Green Infrastructure and Biodiversity 11 Current Situation 11 Vision 12 Key GI Focus Areas 14 4 Making It Happen - GI Delivery 23 Priority GI Projects 23 Governance 23 Funding 23 5 Integrating GI and Biodiversity with Sustainable Development 24 Recommended Approach to Biodiversity for all Planning -

56 & 56A Park Lane, Fen Drayton

56 & 56A PARK LANE, FEN DRAYTON A rare opportunity to acquire a substantial bungalow situated at the end of a private road within delightful established gardens of approximately 0.80 of an acre. Cambridge 9.5 miles, Huntingdon 8.5 miles (London's King's Cross 50 minutes), St Ives 4 miles, A14 1 mile (distances are approximate). Property Summary • Kitchen/Sitting Room, Conservatory/Dining Room, Garden Room, Family Room, Kitchenette, 2 Bedrooms, 2 Bath/Shower Rooms (1 En Suite), Cloakroom. • Outside: Covered Log Store, Parking Area, Workshop, Utility Room, Large Mature Garden. Please read Important Notice on floor plan page 56 & 56A PARK LANE, FEN DRAYTON, CB24 4SW £500,000 (GUIDE PRICE) Description 56/56a Park Lane occupies a superb location at the end of a private road. Converted in 2011 to an individual design, the property is constructed with brick and weatherboard clad elevations under a tiled roof. Originally designed as 2 holiday lets, change of use to residential was granted in August 2016 on the provision that they remained as 2 separate dwellings. In March 2017 change of use to form one dwelling was granted by South Cambridge District Council Ref: S/3565/16/FL. A copy of the planning decision is available from Bidwells or can be viewed within the planning section at South Cambridgeshire District Council. http://www.scambs.gov.uk Outside The property is approached over a gravel driveway leading to a parking area for several vehicles and a Covered Log Store. There is a side access to the rear garden which is mainly laid to lawn bordered by a variety of established shrub beds and mature trees, as well as a Utility Room and Workshop 15' 5" x 8' 8" (4.69m x 2.64m). -

LOCATION Earith Lies Along the River Great Ouse with Access Provided by West View Marina

LOCATION Earith lies along the river Great Ouse with access provided by West View Marina. You can travel along the river south-west towards St Ives or northeast towards Ely and Kings Lynn or join the river Cam into Cambridge. The A14 is a short drive away providing easy access into Cambridge, while Huntingdon railway station provides a fast route to Kings Cross. There is also a bus service to St Ives and Cambridge, as well as a long- distance footpath called the Ouse Valley Way, leading to Stretham and St. Ives. Earith Primary School is rated good by Ofsted, and secondary schooling is provided by Abbey College, Ramsey located about 11 miles (17.7 kilometres) away. It is also rated good by Ofsted. Local amenities include a convenience store/post office, vehicle repair garage, part-time doctors' surgery, and a tandoori takeaway. Earith has one public house, The Crown. ENTRANCE HALL Electric storage heater, airing cupboard. LIVING/DINING ROOM 17' 0" x 14' 0" (5.18m x 4.27m) Windows to rear, re-fitted French doors to garden, windows to side, electric storage heater. KITCHEN 14' 0" x 10' 0" (4.27m x 3.05m) Double glazed windows to side (installed 2019). Fitted with range of base and eye level units with work surface over, one and a half bowl sink and drainer unit, built-in electric oven and halogen hob, space for tumble dryer or dishwasher (with plumbing), washing machine and under counter fridge, intercom receiver. BEDROOM ONE 16' 0" x 14' 0" (4.88m x 4.27m) Re-fitted window to front, dressing area with a range of fitted wardrobes, electric storage heater. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS)

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 7, 2nd edition, as amended by COP9 Resolution IX.1 Annex B). A 3rd edition of the Handbook, incorporating these amendments, is in preparation and will be available in 2006. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House City Road Designation date Site Reference Number Peterborough Cambridgeshire PE1 1JY UK Telephone/Fax: +44 (0)1733 – 562 626 / +44 (0)1733 – 555 948 Email: [email protected] 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: Designated: 28 November 1985 3. Country: UK (England) 4. Name of the Ramsar site: Martin Mere 5. -

NOTICE of POLL Election of Parish Councillors

NOTICE OF POLL Huntingdonshire District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Bluntisham Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of Parish Councillors for Bluntisham will be held on Thursday 7 May 2015, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of Parish Councillors to be elected is eleven. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors BERG 17 Sumerling Way, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Mark Bluntisham, Huntingdon, Cambs, PE28 3XT CURTIS Patch House, 2, Colne Richard I Saltmarsh (+) David W.H. Walton (++) Cynthia Jane Road, Bluntisham, Cambridge, PE28 3LT FRANCIS 1 Laxton Grange, John R Bloor (+) Robin C Carter (++) Mike Bluntisham, Cambs, PE28 3XU GORE 38 Wood End, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Rob Bluntisham, Huntingdon GUTTERIDGE 29 St. Mary's Close, Donald R Rhodes (+) Patricia F Rhodes (++) Joan Mary Bluntisham, Huntingdon, Camb's., PE28 3XQ HALL 7 Laxton Grange, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Jo Bluntisham, Huntingdon, PE28 3XU HIGHLAND 7 Blackbird St, Potton, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Steve Beds, SG19 2LT HIGHLAND 7 Blackbird Street, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Tom Potton, Sandy, Beds, SG19 2LT HOPE 15 St Mary's Close., Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Philippa Bluntisham, -

5 – 7 High Street, Earith Cambridgeshire

5 – 7 HIGH STREET, EARITH CAMBRIDGESHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION Report Number: 1053 May 2014 5 – 7 HIGH STREET, EARITH, CAMBRIDGESHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION Prepared for: Jeremy Hanncok J T Hancock and Associates Ltd On behalf of: Roundwood Restorations Ltd Roundwood Farm Stutton Ipswich Suffolk IP9 2SY By: Martin Brook BA PIfA Britannia Archaeology Ltd 115 Osprey Drive, Stowmarket, Suffolk, IP14 5UX T: 01449 763034 [email protected] www.britannia-archaeology.com Registered in England and Wales: 7874460 May 2014 Site Code ECB4169 NGR TL 3875 7490 Planning Ref. 1201542FUL OASIS Britanni1-178984 Approved By: Tim Schofield Date May 2014 © Britannia Archaeology Ltd 2014 all rights reserved Report Number 1053 5 – 7 High Street, Earith, Cambridgeshire Archaeological Evaluation Project Number 1056 CONTENTS Abstract 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Site Description 3.0 Planning Policies 4.0 Archaeological Background 5.0 Project Aims 6.0 Project Objectives 7.0 Fieldwork Methodology 8.0 Presentation of Results 9.0 Deposit Model 10.0 Discussion & Conclusion 11.0 Project Archive & Deposition 12.0 Acknowledgments Bibliography Appendix 1 Deposit Tables and Feature Descriptions Appendix 2 Specialist Reports Appendix 3 Concordance of Finds Appendix 4 OASIS Sheet Figure 1 Site Location Plan 1:500 Figure 2 CHER Entries Plan 1:10,000 Figure 3 Feature Plan 1:200 Figure 4 Plans, Sections and Photographs 1:100 & 1:20 Figure 5 Sample Sections and Photographs 1:20 1 ©Britannia Archaeology Ltd 2014 all rights reserved Report Number 1053 5 – 7 High Street, Earith, Cambridgeshire Archaeological Evaluation Project Number 1056 Abstract In April 2014 Britannia Archaeology Ltd (BA) undertook an archaeological trial trench evaluation on land at 5 – 7 High Street, Earith, Cambridgeshire (NGR TL 3875 7490) in response to a design brief issued by Cambridgeshire County Council, Historic Environment Team. -

Fenland Experience December 2018 2 CONTENTS

Outline Planning Application Fenland Experience December 2018 2 CONTENTS 01 INTRODUCTION 04 02 SITE AND CONTEXT 06 03 WICKEN FEN NATURE RESERVE 10 04 GETTING TO WICKEN FEN AND CAM WASHES 14 05 FENLAND EXPERIENCE AT WATERBEACH NEW TOWN EAST 16 06 WALKING AND CYCLING AT WATERBEACH NEW TOWN EAST 26 07 A SUITABLE FENLAND EXPERIENCE 30 This document has been prepared and checked in accordance with ISO 9001:2008 Version 1.1 3 01 Introduction Waterbeach New Town is a proposed new settlement 6 km to the north of Cambridge. It leisure and sports uses; a hotel; new primary and secondary schools; green open spaces is a key part of the vision and spatial plan for growth for both the city and the surrounding including parks, ecological areas and woodlands and principal new accesses from the A10 district. The site is entirely within the South Cambridgeshire District Council administrative (Planning Application reference S-0559-17-OL). boundary and is allocated in the Local Plan. The Waterbeach New Town SPD is being prepared by South Cambridgeshire District The site is positioned between the A10, which defines the western boundary of the New Council and will provide detailed guidance about how the new settlement should be Town, and the Cambridge to Ely railway line, which marks its extent to the east. It lies designed, developed and delivered in accordance with modified Local Plan policy SS/5, immediately to the north of the existing village of Waterbeach, and in turn, immediately with an emphasis on ensuring comprehensive development across the site as a whole. -

Littleport Scrapbook 1897-1990 by Mike Petty

Littleport Scrapbook 1897-1990 by Mike Petty Littleport Scrapbook 1897-1990 Extracts from ‘A Cambridgeshire Scrapbook’, compiled by Mike Petty 16 Nov 2016 Introduction Each evening from March 1997 to March 2015 I compiled a ‘Looking Back’ column in the Cambridge News in which I feature snippets from issues of 100, 75, 50 and 25 years ago. I sought out unusual items relating to villages and areas of Cambridge not usually featured These stories are from issues of the Cambridge Daily/Evening/Weekly News of 1897-1990 I can supply actual copies of many of these articles – please contact me. The full set of articles, numbering over 3,000 pages is available at bit.ly/CambsCollection The newspapers are held in the Cambridgeshire Collection together with other Cambridge titles back to 1762. They have a variety of indexes including a record of stories for every village in Cambridgeshire between 1770-1900 and newspaper cuttings files on 750 topics from 1958 to date. I initiated much of the indexing and have many indexes of my own. Please feel free to contact me for advice and assistance. For more details of newspapers and other sources for Cambridgeshire history see my website www.mikepetty.org.uk This index was produced as a part of my personal research resources and would benefit by editing. If you can make any of it work for you I am delighted. But remember you should always check everything! Please make what use of it you may. Please remember who it came from Mike Petty. Mike Petty – www.mikepetty.org.uk bit.ly/CambsCollection Littleport Scrapbook 1897-1990 by Mike Petty Littleport Scrapbook 1897-1990 1897 02 26 The clerk to the Ely Guardians applied for the removal of Tabitha Camm, an eccentric old woman aged 72 years who is living in a tumbled-down old hovel in Littleport fen. -

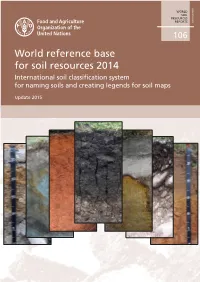

World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014 International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps

ISSN 0532-0488 WORLD SOIL RESOURCES REPORTS 106 World reference base for soil resources 2014 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps Update 2015 Cover photographs (left to right): Ekranic Technosol – Austria (©Erika Michéli) Reductaquic Cryosol – Russia (©Maria Gerasimova) Ferralic Nitisol – Australia (©Ben Harms) Pellic Vertisol – Bulgaria (©Erika Michéli) Albic Podzol – Czech Republic (©Erika Michéli) Hypercalcic Kastanozem – Mexico (©Carlos Cruz Gaistardo) Stagnic Luvisol – South Africa (©Márta Fuchs) Copies of FAO publications can be requested from: SALES AND MARKETING GROUP Information Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Viale delle Terme di Caracalla 00100 Rome, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (+39) 06 57053360 Web site: http://www.fao.org WORLD SOIL World reference base RESOURCES REPORTS for soil resources 2014 106 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps Update 2015 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2015 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

Fen Drayton Villa Investigations

Fen Drayton Villa Investigations Excavation Report No. 2 CAMBRIDGE ARCHAEOLOGICAL UNIT OUSE WASHLAND ARCHAEOLOGY Fen Drayton Villa Investigations (Excavation Report No. 2) Leanne Robinson Zeki, MPhil With contributions by Emma Beadsmoore, Chris Boulton, Vicki Herring, Andrew Hall, Francesca Mazzilli, Vida Rajkovaca, Val Fryer, Simon Timberlake Illustrations by Jon Moller and Andy Hall Principal photography by Dave Webb ©CAMBRIDGE ARCHAEOLOGICAL UNIT UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE March 2016/ Report No. 1333 HER Event Number: ECB4702 PROJECT SUMMARY An archaeological excavation was undertaken by volunteers and the Cambridge Archaeological Unit as a part of the Ouse Washes Landscape Partnership at the site of a possible Roman Villa at the RSPB’s Fen Drayton Lakes reserve, near Cambridge. The fieldwork comprised two 5m x 10m trenches, which were targeted to expose the northern extent of the proposed Roman Villa and southern extent of a potential bathhouse. Excavations revealed additional evidence of Roman occupation, indications of small industry and high-status artefacts. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The project was funded by the Ouse Washes Landscape Partnership Project via the Heritage Lottery Fund, for which particular thanks are conveyed to Mark Nokkert of Cambridge Acre. Permission to excavate on the land was provided by the land owner, the RSPB, which was principally overseen by Robin Standring, and the tenant farmer, Chris Wissen. The volunteering was coordinated by Rachael Brown of Cambridgeshire Acre with Grahame Appleby of the CAU. Dr Keith Haylock, University of Aberystwyth undertook the pXRF measurements. Figure 3’s photographs were produced by Emma Harper. Christopher Evans (CAU) was the Project Manager and work on site was completed by volunteers supervised by Jonathan Tabor, Leanne Robinson Zeki and Francesca Mazzilli of the CAU.