Fittingfeatures Grain-Darts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 1 Apply style tape to your dress form to establish the bust level. Tape from the left apex to the side seam on the right side of the dress form. 1 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 2 Place style tape along the front princess line from shoulder line to waistline. 2 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3A On the back, measure the neck to the waist and divide that by 4. The top fourth is the shoulder blade level. 3 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3B Style tape the shoulder blade level from center back to the armhole ridge. Be sure that your guidelines lines are parallel to the floor. 4 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 4 Place style tape along the back princess line from shoulder to waist. 5 Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 1 To find the width of your center front block, measure the widest part of the cross chest, from princess line to centerfront and add 4”. Record that measurement. 6 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 2 For your side front block, measure the widest part from apex to side seam and add 4”. 7 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 3 For the length of both blocks, measure from the neckband to the middle of the waist tape and add 4”. 8 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 4 On the back, measure at the widest part of the center back to princess style line and add 4”. -

Placket Construction Options

Placket Construction Options 1 Type1: Two Separate Bound Edges on a rectangular stitching box The key to this structure is that the bindings are initially stitched only to the seam allowances on each side, and NOT stitched across the end, of the clipped box, which means that they, and the clipped triangle at the bottom, remain loose and can be arranged before the nal nishing to go on either side of the fabric, as well as either over or under the other, after joining them at the sides. The widths and lengths of the bindings and the space between the sides of the clipped box determine all the other options available in this most exible of all the placket types I know of. Variation 1: Both bindings t inside the stitching box If you cut the bindings so the nished, folded widths of both are equal to or smaller than the space between the initial stitching lines, as shown above, you can arrange both ends at the clipped corners to all go on one side of the fabric (right or wrong side), along with the clipped triangle on the garment. You’ll get the best results if the underlapping binding is slightly smaller than the overlapping one. This can be man- aged by taking slightly deeper seam allowances when you join this piece, so they can initially be cut from the same strip. Or, you can place one end on each side with the Both ends on RS One end on RS, Both ends on WS triangle sandwiched in between. -

Info/How to Examine an Antique Painting.Pdf

How to Examine an Antique Painting by Peter Kostoulakos Before we can talk about the examination process, an overview of how to handle an oil painting is necessary to prevent damage to the work and liability for the appraiser. The checklist below is essential for beginning appraisers to form a methodical approach to examining art in the field without heavy, expensive equipment. Although the information may seem elementary for seasoned appraisers, it can be considered a review with a few tips to organize your observational skills. When inspecting an antique painting, as with any antique, a detailed on the spot, examination should take place. A small checklist covering composition, support, paint layers, varnish, and frame is necessary. Also, a few tools such as a UV lamp, magnifiers, camera, soft brush, cotton swabs, and tape measure are needed. A "behind the scenes" investigation can tell you a great deal about the painting. The name of the artist, title of the painting, canvas maker, date of canvas and stretcher, exhibitions and former owners are some of the things that may be revealed upon close examination. Document your examination with notes and plenty of photographs. Handling Art Older paintings should be thought of as delicate babies. We need to think about the consequences before we pick one up. To prevent acidic oil from our skin to be transferred to paintings and frames, we must cover our hands with gloves. Museum workers have told me that they feel insecure using white, cotton gloves because their grip becomes slippery. I tried the ceremonial gloves used in the military to grip rifles while performing. -

HEG88-237 Sewing with Stripes

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension Extension 1988 HEG88-237 Sewing With Stripes Rose Marie Tondl University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Tondl, Rose Marie, "HEG88-237 Sewing With Stripes" (1988). Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. 1401. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist/1401 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Extension at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HEG88-237 Sewing With Stripes Sewing with stripes is easier when you know what pitfalls to avoid. This Guide covers pattern selection, yardage requirements, stripe strategies and more. Rose Marie Tondl -- Extension Clothing Specialist z Pattern Selection z Yardage Requirements z Stripe Strategy z The Match Game with Crosswise Stripes z The Match Game with Lengthwise Stripes z Diagonally Striped Fabric z Pleating a Stripe z Sewing Techniques Any way you line them up, stripes make a striking fashion statement. You can be as bold or as subtle as you like with stripes. Nothing gives a garment less appeal than stripes that do not meet and match at seams. Simply defined, a stripe is a band or line which may be wide, narrow or in-between. Stripes can be horizontal vertical or diagonal, even or uneven, and one color, two color or multicolor. -

WRAP DRESS a DIY Pattern for Use with Alabama Stitch Book, Alabama Studio Style, Alabama Studio Sewing + Design, and Alabama Studio Sewing Patterns

WRAP DRESS A DIY pattern for use with Alabama Stitch Book, Alabama Studio Style, Alabama Studio Sewing + Design, and Alabama Studio Sewing Patterns theschoolofmaking.alabamachanin.com © Alabama Chanin™ 2017 Wrap Dress Instructions 1. Baste Neckline and Armholes To ensure that the neckline and armholes don’t stretch while you’re constructing your garment, use a single strand of all-purpose thread to baste around the neckline and curved edges of each piece. 2. Add Embroidery If you choose to stencil and/or embroider your project, add this to the right side of the cut Wrap Dress top-layer pieces, and let stenciled images dry thoroughly before proceeding. Add embellishment as desired. Use one of our Alabama Studio Series books for inspiration. If you’re adding beading, avoid beading in the 1/4” seam allowance. 3. Prepare for Construction After completing embellishment, choose Inside or Outside Floating or Felled Seams (see our Alabama Studio Book Series) for your garment. You will pin with fabric’s wrong sides together for seams visible on the outside of the garment or with fabric’s right sides together for seams that are finished on the inside of the garment. When pinning knit seams for construction, it is important to follow a method we call “pinning the middle.” With right sides together for inside seams and wrong sides together for outside seams, start by pinning the top of your seam, and follow by pinning the bottom of your seam. After pinning both top and bottom, place one pin in the middle, between the two initial pins. -

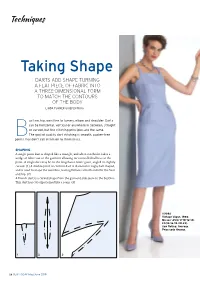

Taking Shape DARTS ADD SHAPE TURNING a FLAT PIECE of FABRIC INTO a THREE-DIMENSIONAL FORM to MATCH the CONTOURS of the BODY LINDA TURNER GRIEPENTROG

Techniques Taking Shape DARTS ADD SHAPE TURNING A FLAT PIECE OF FABRIC INTO A THREE-DIMENSIONAL FORM TO MATCH THE CONTOURS OF THE BODY LINDA TURNER GRIEPENTROG ustline, hip, waistline to tummy, elbow and shoulder. Darts can be horizontal, vertical or anywhere in between, straight or curved, but the stitching principles are the same. BThe goal of quality dart stitching is smooth, pucker-free points that don’t call attention to themselves. SHAPING A single-point dart is shaped like a triangle, and when stitched it takes a wedge of fabric out of the garment allowing for controlled fullness at the point. A single dart may be on the lengthwise fabric grain, angled or slightly curved. (1) A double-point or contour dart is diamond or rugby ball shaped, and is used to shape the waistline, leaving fullness at both ends for the bust and hip. (2) A French dart is a curved shape from the garment side seam to the bustline. This dart has cut edges joined like a seam. (3) V9082 Vintage Vogue, 1960. Misses’ A5(6-8-10-12-14) E5(14-16-18-20-22). Sew Rating: Average. Price code Orange. Illustrations: Theresa O’Connell Theresa Illustrations: 1 2 3 26 SEW TODAY May/June 2019 MARKING to anchor the stitches. Stitch (7) and stitch toward the point, Darts are indicated on the along the line, removing the A third technique for dart then repeat for the other pattern tissue by either solid pins as you get to them. Taper point, slightly overlapping or dashed lines and a dot the stitching to the point the beginning stitching lines at the point. -

Bonded Fabrics

L-897 BONDED FABRICS Graham Hard Kay Elmore Hazel Roberts • Fannie Brown Eaton • Joanne Thurber* • Woven wool interlining bonded to fabric for thermal qualities, body and stability. • Non-woven fabric bonded to woven face fab ric to add bulk and warmth. • Cotton knit backing bonded to face fabric to improve absorbency, bulk and drape. • Nylon net backing bonded to face fabrics such as lace to add stability and retain ap pearance of face fabric. Standards of Performance for Bonded Fabrics Manufacturers of bonded fabrics and trade as sociations are now setting standards for perform ance in bond and wear as well as performance in laundering and dry cleaning. There is a general agreement to produce qual ity bonded fabrics which: • Withstand a reasonable number of washings and drycleanings. What Are Bonded Fabrics? • Have shrinkage within a certain acceptable Bonded fabrics are made of two or more amount. already-constructed fabrics held together by wet adhesives or thin polyurethane foam. Wet bond • Do not peel, pucker, crack or bubble. ing adhesives aid in preserving the original hand • Maintain drape and ability to breathe. and drape of fabrics. Foam bonding adds body, • Do not become stiff. shape retention and thermal qualities where needed in fabrics. • Do not absorb odor. • Will resist discoloration. Types of Bonded Fabrics • Will have no surface evidence of adhesive. The original bonded fabrics combined a woven f ce fabric with an acetate knit liner. There are What Bonded Fabrics Offer the Consumer v riou bonded fabrics on the consumer market today. These include polyurethane foam, bonded • More styling and design ideas are made to face fabric or between two fabrics, and wet possible. -

BERNINA Virtuosa 150 / 160 Manual

BERNIN¡[ lnstruction Manual & Sewing Manual -:f=f olo c"" f- al q: ta vtrl!,osa r50 CLC te! BEBNII{II o\c e1c 1 tr!Lt6 .l 9(.{È #,t ,' o':: o't' a": : ¡'i, ¿'il O''_ a'i c,"I ryi'l c"ü€" 1 ,r=-l . .,8 "0., " "o t T ''1,:: t{Ë -{=f o\c !* a* vtrtuoså 160 o Lo Gttu'ltt ACßNINA ¡c o o sõ'a- rr' rt a i.o :â¡ o o\ a', a i o:i o'l o a'il s"[ c"i s'{ 6"1 6rf 'll ',I $ ',t \¡ tø'ø..3"ø*, ry'øm a, %'{* ,øør%mryruøz 'øryrfu QUILTER'S BERNIN¡f EDITION BERNIN'f Made in Switzerland Made ¡n Sw¡tzerland Safegr instructíons 'ì I IVH PORTANT SAFETY I I\¡ STRI,J CTilON I 5 When using an electrical machine, basic safety 8. Do not pull or push fabric while stitching. lt may ì precautions should always be followed, including the deflect the needle causing it to break. f ollowing. 9. Turn power switch to <0> when making any adjust- Read all instructions before using this sewing machine. ments in the needle area, such as threading or chang- ing the needle, threading the bobbin or changing When the machine is not in use, it should be disconnected the presser foot. from the electricity supply by removing the plug from the outlet. 10. Always unplug the sewing machine from the electri- cal outlet when removing covers, lubricating or when making any other user servicing adjustments men- ÐANGEM tioned in this instruction manual. -

4-H Textile Science Textile Arts Projects. INSTITUTION Pennsylvania State Univ., Univeriity Park

DOCUMENT RESUME ED.379 510 CE 068 348 AUTHOR Scholl, Jan TITLE 4-H Textile Science Textile Arts Projects. INSTITUTION Pennsylvania State Univ., Univeriity Park. Cooperative Extension Service. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 24p.; For related documents, see CE 068 343-347. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Instructional Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Clothing; Clothing Design; *Clothing Instruction; *Design Crafts; Elementary Secondary Education; Extracurricular Activities; Home Economics; *Home Management; *Learning Activities; *Student Organizations; Student Projects; *Textiles Instruction IDENTIFIERS *4 H Programs; Crocheting; Knitting; Weaving ABSTRACT This packet contains three 4-H textile arts projects for students in the textile sciences area. The projects cover weaving, knitting, and crocheting. Each project provides an overview of what the student will learn, what materials are needed, and suggested projects for the area. Projects can be adapted for beginning, intermediate, or advanced levels of skills. A step-by-step plan for doing the project, with instruction sheets and line drawings is included. Also included are a project record, ideas for sharing the project with others, and suggestions for additional projects. (KC) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * from the original document. *********************************************************************** 4-H Textile Science Textile Arts Projects U S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Ofj Ice of Educational Research and Improvemont E r.1 CATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY received from the person or organization originating it. Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality. Points of view or opinions stated in this document do not necessarily represent official OERI position or policy. -

Savile-Row-Inside-Out.Pdf

Savile Row: Inside Out 1 Savile Row BeSpoke aSSociation he Savile Row Bespoke Association is dedicated to protecting and promoting Tthe practices and traditions that have made Savile Row the acknowledged home of the best bespoke tailoring and a byword for unequalled quality around the world. The SRBA comprises of fifteen member and associate houses, who work together to protect and champion the understanding of bespoke tailoring and to promote the ingenious craftsmen that comprise the community of Savile Row. The SRBA sets the standards that define a Savile Row bespoke tailor, and all members of the Association must conform to the key agreed definitions of a bespoke suit and much more besides. A Master Cutter must oversee the work of every tailor employed by a member house and all garments must be constructed within a one hundred yard radius of Savile Row. Likewise, every member must offer the customer a choice of at least 2,000 cloths and rigorous technical requirements are expected. For example, jacket foreparts must be entirely hand canvassed, buttonholes sewn, sleeves attached and linings felled all by hand. It takes an average 50 plus hours to produce a suit in our Savile Row cutting rooms and workshops. #savilerowbespoke www.savilerowbespoke.com 2 1 Savile Row: inSide out Savile Row: Inside Out looks inside the extraordinary world of bespoke tailoring; an exclusive opportunity to step behind the scenes and celebrate the tailor’s art, the finest cloth and the unequalled expertise that is British Bespoke. A real cutter will be making a real suit in our pop-up cutting room in front of a collection of the work – both ‘before’ and ‘after’ to show the astonishing level of craftsmanship you can expect to find at Savile Row’s leading houses. -

Princess Seams

Princess Seams 11.310 Page 1 Princess seams are a variation of darts, allowing the creation of a fitted garment through the use of shaped seams. They start at the waist and travel toward the most prominent part of the body in that quadrant of the garment. For example, on a bodice front they travel over or near (within 1 1/2") the bust point, while on the bodice back they travel over or near the shoulder blades. Though less common, skirt or pants princess seams start at the waist and travel over or near the fullest part of the abdomen and/or near the fullest part of the buttocks. Style Options Because the seam always starts at the waist, names of princess seam styles refer to the ending point. Two classic styles of princess seams are shoulder (1) and armhole (2). A princess seam can end almost anywhere— in the neckline (3) or in the center front (4), depending on the garment design. 1 2 Different From Darts To see how a princess seam is related to darts, place the front and side front pattern pieces of an armhole princess-seamed bodice (5) side by side with a bodice front containing a waist and an armhole bust dart (6). A princess seam is actually the combined waist and bust darts, with the curved lined smoothed between and seam 3 4 allowances added to the new edges on each pattern piece. Great Grains Many sewers find curved seams easier to sew and fit than curved bust darts. Princess- seamed bodices allow for a more precise use of the garment fabric grain than darted bodices, because each pattern piece has its own grainline. -

Pattern Layout, Pinning and Cutting

Lesson Pattern Layout, Pinning 8 and Cutting Objectives This lesson will help you to • identify the various ways fabric may be folded in preparation for layout, pinning, and cutting. • correctly lay out a pattern. • give reasons for various layout, pinning, and cutting procedures. • interpret layout, pinning, and cutting information found on the pattern instruction sheet. Words to Know lengthwise fold double fold even plaid partial fold repeat uneven plaid crosswise fold Gathering Information Following the correct pattern layout will help ensure that your garment is cut out on- grain. Pinning and cutting your garment carefully will avoid wasting fabric. This lesson will provide the information you need to lay out, pin, and cut out your pattern pieces. You will first need to make sure the cut ends of your fabric are on-grain. If they are off- grain, follow the directions in Lesson 4, “Fabric Preparation,” to straighten the grain before preparing the fabric for pattern layout. Folding Fabric can be folded in a variety of ways the Fabric before pattern pieces are positioned for cutting. The type of fold used depends on • the number of pattern pieces that must be placed on a folded edge • the fold that results in the most economic use of the fabric • the width of the fabric • the pattern size Pattern companies have already taken these factors into consideration for you. Therefore, you should fold your fabric as shown in the diagram found on your pattern instruction sheet. (Continued) 101 L5-8.indd 101 8/8/2012 8:59:57 AM 102 Successful Sewing Lengthwise fold.