KANAUJI of KANPUR:ABRIEF OVERVIEW Pankaj DWIVEDI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Answered On:15.05.2002 Work Packages on National Highway P.D

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ROAD TRANSPORT AND HIGHWAYS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:7343 ANSWERED ON:15.05.2002 WORK PACKAGES ON NATIONAL HIGHWAY P.D. ELANGOVAN Will the Minister of ROAD TRANSPORT AND HIGHWAYS be pleased to state: (a) the details of the work packages tendered so far and the successful bidders of those work packages National Highways-wise, the East West Corridor project and the Golden Quadrilateral project; (b) whether the Government have decided to debar some of the road contractors entrusted with fourlaning works, previously; and ( (c) if so, the details thereof and the reasons therefor? Answer THE MINISTER OF STATE OF THE MINISTRY OF ROAD TRANSPORT AND HIGHWAYS (MAJOR GENERAL (RETD.) B.C. KHANDURI) (a) Details are at Annex. (b) & (c) M/s PT Sumber Mitra Jaya has been debarred in October, 2001, from participating in any bidding process due to non- adherence of contract conditions. ANNEX REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PART (a) OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 7343 FOR ANSWER ON 15.05.2002 ASKED BY SHRI P.D. ELANGOVAN REGARDING WORK PACKAGES ON NATIONAL HIGHWAY. Details of work packages tendered so far and the successful bidders for East-West Corridor Project and Golden Quadrilateral Project. Golden Quadrilateral Project (Completed Stretches) Sl.No. Stretch NH Length State Name of the Contractor 1 Barwa Adda-BarakarKm 398.75 - km 442 2 43.00 Jharkhand BSC-RBM-PATI (JV) 2 Raniganj-PanagarhKm 475 - km 517 2 42.00 West Bengal BSC-RBM-PATI (JV) 3 Sira BypassKm 122 - km 116 4 5.80 Karnataka Maytas Infrastructure Ltd 4 Vijayawada-Rajamundry Section (near Eluru)Km 75 - km 80 5 5.00 Andhra Prad. -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

Neo-Vernacularization of South Asian Languages

LLanguageanguage EEndangermentndangerment andand PPreservationreservation inin SSouthouth AAsiasia ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 7 Language Endangerment and Preservation in South Asia ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 7 PUBLISHED AS A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION LANGUAGE ENDANGERMENT AND PRESERVATION IN SOUTH ASIA Special Publication No. 7 (January 2014) ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 USA http:/nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I PRESS 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822-1888 USA © All text and images are copyright to the authors, 2014 Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives License ISBN 978-0-9856211-4-8 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4607 Contents Contributors iii Foreword 1 Hugo C. Cardoso 1 Death by other means: Neo-vernacularization of South Asian 3 languages E. Annamalai 2 Majority language death 19 Liudmila V. Khokhlova 3 Ahom and Tangsa: Case studies of language maintenance and 46 loss in North East India Stephen Morey 4 Script as a potential demarcator and stabilizer of languages in 78 South Asia Carmen Brandt 5 The lifecycle of Sri Lanka Malay 100 Umberto Ansaldo & Lisa Lim LANGUAGE ENDANGERMENT AND PRESERVATION IN SOUTH ASIA iii CONTRIBUTORS E. ANNAMALAI ([email protected]) is director emeritus of the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore (India). He was chair of Terralingua, a non-profit organization to promote bi-cultural diversity and a panel member of the Endangered Languages Documentation Project, London. -

Pukhraya Dealers Of

Dealers of Pukhraya Sl.No TIN NO. UPTTNO FIRM - NAME FIRM-ADDRESS 1 09144100002 PH0000877 HINDUSTAN AUTO MOBILE BHOGNIPUR. KNP DEHAT 2 09144100016 PH0001337 JAGNNATH RAM SEWAK POKHARPUR KNP DEHAT 3 09144100021 PH0001487 GOVIND NARAIN MANOJ KUMAR MOOSANAGAR KNP DEHAT 4 09144100035 PH0050288 MAHAVEER SACHAN GHATAMPUR.KNP DEHAT 5 09144100040 PH0003038 INDIA BRICK FIELD GHATAMPUR KANPUR DEHAT 6 09144100049 PH0003354 SINGH BROTHERS NONAPUR BHOGNIPUR.KNP DEHAT 7 09144100054 PH0003669 PATEL BRICK FIELD GHATAMPUR KNP DEHAT 8 09144100068 PH0002591 RAM BABU KRISHNA BABU MOOSANAGAR KNP DEHAT 9 09144100073 PH0003997 NEW BAJRANG BRICK FIELD RENGWA KNP DEHAT 10 09144100087 PH0004356 GAURISHANKER KUTEER UDYOG PUKHRAYAN KNP DEHAT 11 09144100092 PH0002174 N.BRICK FIELD SUJGAWAN KNP DEHAT 12 09144100101 PH0002707 SINGH BRICK FIELD KUAAN KHARA GHATAMPUR. 13 09144100115 PH0005132 NEW NATIONAL BRICK FIELD YATIMPUR BHOGNIPUR KANPUR DEHAT 14 09144100120 PH0002465 SINKANDRA BRICK FIELD SINKANDRA. KNP DEHAT 15 09144100129 PH0006223 BAJPAI MEDICAL STORE RAJPUR SICUNDERA KANPUR DEHAT 16 09144100134 PH0005270 JAI BAJRANG BRICK FIELD MANCHA BHOGNIPUR RAIGAWAN KANPUR DEHAT 17 09144100148 PH0005496 SUPER EENTA UDHYOG MAHMOOD PUR BHOGNIPUR KANPUR 18 09144100153 PH0005714 PUKHRAYAN KUTEER UDYOG MACHA BHOGNIPUR KANPUR DEHAT 19 09144100167 PH0005698 MANOJ AUTOMOBILES MAIN ROAD NEAR BUS STAND PUKHRAYAN KNP. 20 09144100172 PH0005977 AYAZ ALI AHRAULI SHAIKH PUKHRAYAN KANPUR DEHAT 21 09144100186 PH0006057 JANTA TROLLY KRI.YANTRA & PUKHRAYAN KANPUR DEHAT REP.WORKS 22 09144100191 -

Braj Bhasha Mayank Jain1, Yogesh Dawer2, Nandini Chauhan2, Anjali Gupta2 1Jawaharlal Nehru University, 2Dr

Developing Resources for a Less-Resourced Language: Braj Bhasha Mayank Jain1, Yogesh Dawer2, Nandini Chauhan2, Anjali Gupta2 1Jawaharlal Nehru University, 2Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar University Delhi, Agra {jnu.mayank, yogeshdawer, nandinipinki850, anjalisoniyagupta89}@gmail.com Abstract This paper gives the overview of the language resources developed for a less-resourced western Indo-Aryan language of India - Braj Bhasha. There is no language resource available for Braj Bhasha. The paper gives the detail of first-ever language resources developed for Braj Bhasha which are text corpus, BIS based POS tagset and annotation, Universal Dependency (UD) based morphological and dependency annotation. UD is a framework for cross-linguistically consistent grammatical annotation and an open community effort with contributors working on over 60 languages. The methodology used to develop corpus, tagset, and annotation can help in creating resources for other less-resourced languages. These resources would provide the opportunity for Braj Bhasha to develop NLP applications and to do research on various areas of linguistics - cognitive linguistics, comparative linguistics, typological and theoretical linguistics. Keywords: Language Resources, Corpus, Tagset, Universal Dependency, Annotation, Braj Bhasha 1. Introduction Hindi texts written in Devanagari. Since the script of Braj Braj or Braj Bhasha1 is a Western Indo-Aryan language Bhasha is Devanagari, the OCR tool gave quite a spoken mainly in the adjoining region spread over Uttar satisfactory result for Braj data. The process of Pradesh and Rajasthan. In present times, when major digitization is a two-step procedure. First, the individual developments in the field of computational linguistics and pages of books and magazines were scanned using a high- natural language processing are playing an integral role in resolution scanner. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern -

Appendix III: List of Locations Where Printers And

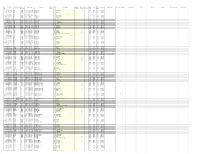

A Appendix-III List of Locations where Printers and MFP’s are required to be installed as mentioned in schedule of requirement for Subordinate Courts/ DLSAs & TLSCs/ JTRI, Lucknow Chart-I List of Subordinate Courts and JTRI with Printers required under Phase-II of eCourts Project District / Outlying Court/Railway Total Court Duplex Laser Jet MFD Network Sl.No. District Courts Rooms Network Printers Printers 1 Agra Railway Court, Agra 1 1 1 2 Agra Outlying Court Fatehabad, Agra 1 1 1 3 Agra District & Session Court, Agra 2 2 2 4 Aligarh Railway Court, Aligarh 1 1 1 5 Aligarh Outlying Court Khair, Aligarh 1 1 1 District & Sessions Court 2 2 2 6 Allahabad Allahabad 7 Allahabad Railway Court, Allahabad 1 1 1 District & Session Court, 8 Ambedkar Nagar Ambedkarnagar 8 8 8 9 Auraiya District & Sessions Court, Auraiya 9 9 9 10 Auraiya Outlying Court Bidhuna 1 1 1 District & Session Court, 11 Azamgarh Azamgarh 7 7 7 12 Baghpat District & Sessions Court, Baghpat 3 3 3 13 Ballia District & Sessions Court, Ballia 3 3 3 14 Balrampur Outlying Court, Utraula 1 1 1 15 Banda Railway Court, Banda 1 1 1 16 Banda Outlying Court, Attra, Banda 1 1 1 17 Banda Outlying Court, Baberu, Banda 1 1 1 18 Banda District & Session Court, Banda 3 3 3 District & Sessions Court, 19 Barabanki Barabanki 3 3 3 20 Bareilly Outlying Court,Baheri, Bareilly 1 1 1 Outlying Court, Nawabganj, 1 1 1 21 Bareilly Bareilly 22 Bareilly Outlying Court, Faridpur, Bareilly 1 1 1 23 Bareilly District & Sessions Court, Bareilly 1 1 1 24 Basti District & Sessions Court, Basti 5 5 5 District -

Prabháta Sam'giita

Prabháta Sam'giita Songs of the New Dawn A brief introduction Renaissance Artists & Writers Association A New Dawn • Prabhata Samgiita – music of a new dawn • 5018 songs • From Indian classical to folk music • Written and composed by: – Shri Prabhata Rainjana Sarkar • Between 1982 and 1990 Variety of Themes • Devotional • Mystical love • Seasons • Ecology • Social consciousness • Marching songs • Stages, feelings & experiences in spiritual meditation • Krs'n'a •Shiva Languages Used • Most songs are in Bengali • Over 40 songs are composed in other languages, including: –English –Sanskrit (language for literary & spiritual uses) –Hindi (vocabulary borrows from Sanskrit, non-Persian & non-Arabic) –Urdu (similar to elementary Hindi, vocabulary borrows from Persian & Arabic) –Angika (spoken in in Bihar, Jharkhand & West Bengal) –Maithili (spoken in North-East Bihar & Nepal) Northern-Central India Some Genres of Prabhata Samgiita • Kiirtan songs • Tappa songs • Thumri songs • Gazal songs • Kawali songs • Baul songs • Jhumur songs Kiirtan Songs • Kiirtan is a special type of devotional song style • Centres around singing about the Supreme Entity (God) • Developed towards the end of the 12th century through Jayadeva’s composition of the Gita Govinda (around 1178 AD) • These are Sanskrit love poems saturated with madhura bhava (high state of devotional sentiment and Divine Love) Kiirtan Songs • During the 15th century Dwija Chandidas (1390 -1450) advocated Krishna kiirtans • These are songs in praise of Lord Krishna as the incarnation of the Supreme -

Final Updation Sheet by HIMS (05.11.2015)

S. State Name District Name Sub Health Facility Town Name Village S No. Facility Name Category Notional/ Bed Facility Location Is IPHS Area Type Area Covered Population Covered Village Served PIN Code Latitude Longitude Linked Facility Type Linked Facility No. District Name Name Physical Count Type Survey Name 1 Uttar Pradesh Agra DHQ Primary Health Centres Agra M Corp 1 Bundukatra P Public Urban NO Plain Area 2 Uttar Pradesh Agra DHQ Primary Health Centres Agra M Corp 2 Chhatta P Public Urban NO Plain Area 3 Uttar Pradesh Agra DHQ Primary Health Centres Agra M Corp 3 dehtora P Public Urban NO Plain Area 4 Uttar Pradesh Agra DHQ Primary Health Centres Agra M Corp 4 Gummat Takht Pahalwan Devari Road P Public Urban NO Plain Area 5 Uttar Pradesh Agra DHQ Primary Health Centres Agra M Corp 5 Hariparvat east P Public Urban NO Plain Area 6 Uttar Pradesh Agra DHQ Primary Health Centres Agra M Corp 6 Hariparvat West P Public Urban NO Plain Area 7 Uttar Pradesh Agra DHQ Primary Health Centres Agra M Corp 7 Jagdishpura P Public Urban NO Plain Area 8 Uttar Pradesh Agra DHQ Primary Health Centres Agra M Corp 8 Jamunapur P Public Urban NO Plain Area 9 Uttar Pradesh Agra DHQ Primary Health Centres Agra M Corp 9 Jivnimandi P Public Urban NO Plain Area 10 Uttar Pradesh Agra DHQ Primary Health Centres Agra M Corp 10 Lohamandi IInd P Public Urban NO Plain Area 11 Uttar Pradesh Agra DHQ Primary Health Centres Agra M Corp 11 Lohamandi Ist P Public Urban NO Plain Area 12 Uttar Pradesh Agra DHQ Primary Health Centres Agra M Corp 12 Mantola P Public Urban NO -

Brief Notes on Mother Tongues , Punjab

CIENSlJJS Of DNDIA 1971 PUNJAB BRIEF NOTES ON MOTHER TONGUES (Based on 1961 Returns) By 315.455 R. C. NIGAM 1971 ~NT REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA IF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA Mot Ton (LANGUAGE DIVISION) LIST OF MOTHER-TONGUES (1961) PUNJAB SI. Name of Mother Name in Local Comments, if any No. tongues with Script variant spellings in brackets 1 2 3 4 Adivasi ( Adibasi, Could be helpful if ~J(.ci Adiwasi) fic tribal/community name could be linked up with mother-tongue name. '2 AfghanijKabuli/ ~GorTol t~T~:81 jU'tl"3.' Pakhto/Pashto/ u;:;i'a!uo Tol Pathani 3 African Return is after the name of the continent. Spe cificmother-tongue names will have to be as certained. 4 Aia Alam Unclassified in 1961 Census. Will need further scrutiny. 5 Almori 6 Anal "POC3 7 Arabic/Arbi »{CI~l In 1961 Census some Urdu speakers also had returned Arabic/ Arbi as their mother- tongue. S Assamese ( Assami) WF[ll-il 9 Awadhi { Avadi) »{~l 10 Baghelkhandi ~ti18ci~1 (Bhugelkhud) 2 SI. Name of Mother Name in Local Comments, if any No. tongues with Script variant spellings in brackets 1 2 3 4 11 Bagri ( Bagari, Bagria, Bahgri ) 12 Bagri-Rajasthani ~TaJ~l-'aTtlRe: T'()l 13 Bahawalpuri ~T~'Sy''al 14 Baliai ( BaHam) e 81",,1 E1 15 Balochi/Baluchi ri~l 16 Bangaru ( Bangru, ~taJil. If returned again in Banger, Bangri) 1971, then location of speakers at the village level need be specified. 17 Baori (Bawria, ~l){a1 The name of at least Bawaria, Boari, one village of their Boria) concentration from the state will be required to be noted. -

Azamgarh Dealers Of

Dealers of Azamgarh Sl.No TIN NO. UPTTNO FIRM - NAME FIRM-ADDRESS 1 09185100008 AZ0019063 BOMBAY SUPARY STORE CHAUKTAHSIL SADAR, AZAMGARH. 2 09185100013 AZ0039267 BAJRANG IRON STORE THEKMA TAHSIL LALGANG AZAMGARH 3 09185100027 AZ0055527 BARBWAL HOMAO HALL ASIFGANJ,SADAR, AZAMGARH. 4 09185100032 AZ0058356 GULAB CHAND BRIJ PAL DAS ASIFGANJ, AZAMGARH. 5 09185100046 AZ0067666 MEDICO PHARMA AGENCY KURMI TOLA SADAR, AZAMGARH. 6 09185100051 AZ0069266 HAINIMEN PYOUR DRUGS COMPANY CIVIL LINES, AZAMGARH. 7 09185100065 AZ0080507 RAM LAKHAN JAISWAL TARWA, AZAMGARH. 8 09185100070 AZ0074855 DHARM DAV CONT. SUFDDINPUR AZAMGRH 9 09185100079 AZ0080734 RAM MEDICAL AGENCY PHARPUR AZAMGARH 10 09185100084 AZ0081089 VINDO GLASS IMPORIAL CHAUK TAHSIL SADER AZAMGARH 11 09185100098 AZ0086052 RAM JATAN YADAV B.K.O. DAGARPUR, AZAMGARH. 12 09185100107 AZ0090190 VIDAYRTHI PUSTAK MANDIR PAHARPUR, AZAMGARH. 13 09185100112 AZ0090328 RAVENDRA TRADERS DIHA AZAMGARH 14 09185100126 AZ0093095 RAJENDRA KASHTHA INDUSTRIES KAPTANGANJ, AZAMGARH. 15 09185100131 AZ0094057 MURALI COLD STORES & ICE FACTARI BELAISA, AZAMGARH. 16 09185100145 AZ0095670 DHANAI RAM PYARE LAL LAL GANJ AZAMGRH 17 09185100150 AZ0096280 ROYAL MEDICAL STORE KHATRI TOLA, AZAMGARH. 18 09185100159 AZ0097079 RAM ADHAR CONTRACTOR KAPTANGANJ, AZAMGRH. 19 09185100164 AZ0097738 RAMA INT BHATTA SARRA AZAMGARH 20 09185100178 AZ0099868 ROSHANI MAHAL KHATRI TOLA, AZAMGARH. 21 09185100183 AZ0101920 BALIRAM ENTERPRISES LALGANJ T.LALGANJ,AZAMGARH. 22 09185100197 AZ0102036 RANJEET SINGH THEKEDAR AKSHAIBAR, AZAMGRH. 23 09185100206 AZ0103127 BENI MEDICAL HALL UTROULA BUDHANPUR AZAMGARH. 24 09185100211 AZ0103957 ROHITAS TRADERS CO. HARI KI CHUNGI AZAMGARH 25 09185100225 AZ0105181 RAM DARASH B.K.O. HATHIPUR, AZAMGARH. 26 09185100230 AZ0105815 RAM PHER YADAV ENT BHATTA HAKARIPAR, AZAMGARH. 27 09185100239 AZ0106312 CHASMA SAGAR MATVARGANJ, AZAMGARH. 28 09185100244 AZ0110652 KISAN AUTO CENTER BOMBAY HOUSE,ROADWAYS, AZAMGARH. -

Chapter One: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India

Chapter one: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India 1.1 Introduction: India also known as Bharat is the seventh largest country covering a land area of 32, 87,263 sq.km. It stretches 3,214 km. from North to South between the extreme latitudes and 2,933 km from East to West between the extreme longitudes. On this 2.4 % of earth‟s surface, lives 16% of world‟s population. With a population of 1,028,737,436 variations is there at every step of life. India is a land of bewildering diversity. India is bounded by the Indian Ocean on the Figure 1.1: India in World Population south, the Arabian Sea on the west and the Bay of Bengal on the east. Many outsiders explored India via these routes. The whole of India is divided into twenty eight states and seven union territories. Each state has its own cultural and linguistic peculiarities and diversities. This diversity can be seen in every aspect of Indian life. Whether it is culture, language, script, religion, food, clothing etc. makes ones identity multi-dimensional. Ones identity lies in his language, his culture, caste, state, village etc. So one can say India is a multi-centered nation. Indian multilingualism is unique in itself. It has been rightly said, “Each part of India is a kind of replica of the bigger cultural space called India.” (Singh U. N, 2009). Also multilingualism in India is not considered a barrier but a boon. 17 Chapter One: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India Languages act as bridges because it enables us to know about others.