Railroad Exhibit Catalog Final.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

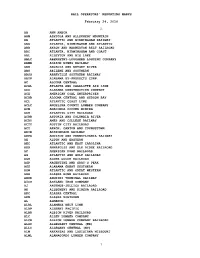

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 a AA

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 A AA ANN ARBOR AAM ASHTOLA AND ALLEGHENY MOUNTAIN AB ATLANTIC AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY ABA ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND ATLANTIC ABB AKRON AND BARBERTON BELT RAILROAD ABC ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND COAST ABL ALLEYTON AND BIG LAKE ABLC ABERNETHY-LOUGHEED LOGGING COMPANY ABMR ALBION MINES RAILWAY ABR ARCADIA AND BETSEY RIVER ABS ABILENE AND SOUTHERN ABSO ABBEVILLE SOUTHERN RAILWAY ABYP ALABAMA BY-PRODUCTS CORP. AC ALGOMA CENTRAL ACAL ATLANTA AND CHARLOTTE AIR LINE ACC ALABAMA CONSTRUCTION COMPANY ACE AMERICAN COAL ENTERPRISES ACHB ALGOMA CENTRAL AND HUDSON BAY ACL ATLANTIC COAST LINE ACLC ANGELINA COUNTY LUMBER COMPANY ACM ANACONDA COPPER MINING ACR ATLANTIC CITY RAILROAD ACRR ASTORIA AND COLUMBIA RIVER ACRY AMES AND COLLEGE RAILWAY ACTY AUSTIN CITY RAILROAD ACY AKRON, CANTON AND YOUNGSTOWN ADIR ADIRONDACK RAILWAY ADPA ADDISON AND PENNSYLVANIA RAILWAY AE ALTON AND EASTERN AEC ATLANTIC AND EAST CAROLINA AER ANNAPOLIS AND ELK RIDGE RAILROAD AF AMERICAN FORK RAILROAD AG ATLANTIC AND GULF RAILROAD AGR ALDER GULCH RAILROAD AGP ARGENTINE AND GRAY'S PEAK AGS ALABAMA GREAT SOUTHERN AGW ATLANTIC AND GREAT WESTERN AHR ALASKA HOME RAILROAD AHUK AHUKINI TERMINAL RAILWAY AICO ASHLAND IRON COMPANY AJ ARTEMUS-JELLICO RAILROAD AK ALLEGHENY AND KINZUA RAILROAD AKC ALASKA CENTRAL AKN ALASKA NORTHERN AL ALMANOR ALBL ALAMEDA BELT LINE ALBP ALBERNI PACIFIC ALBR ALBION RIVER RAILROAD ALC ALLEN LUMBER COMPANY ALCR ALBION LUMBER COMPANY RAILROAD ALGC ALLEGHANY CENTRAL (MD) ALLC ALLEGANY CENTRAL (NY) ALM ARKANSAS AND LOUISIANA -

Jay T. Last Collection of American Transportation Prints: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pk0h51 Online items available Jay T. Last Collection of American Transportation Prints: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Diann Benti. Rare Books Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: 626-405-3473 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2013 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Jay T. Last Collection of American priJLC_TRAN 1 Transportation Prints: Finding Aid Descriptive Summary Title: Jay T. Last Collection of American Transportation Prints Dates (inclusive): approximately 1833-approximately 1911 Bulk dates: 1840-1900 Collection Number: priJLC_TRAN Collector: Last, Jay T. Extent: approximately 167 items Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens: Rare Books Department Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: 626-405-3473 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The prints in the Jay T. Last Collection of American Transportation consist of over 160 prints related to land-based modes of transportation primarily in the United States. The collection dates from the 1830s into the early 20th century and consists largely of materials pertaining to railroads, with additional items concerning the bicycle and carriage, coach, and wagon industries. Item types include advertising cards, posters, broadsides, maps, timetables, views, and other visual materials primarily produced by transportation-affiliated entities such as railroad companies and vehicle and parts manufacturers. The collection features lithographs produced by American artists, printers, and publishers, as well as engravings, letterpress and woodblock prints. Topical subjects include transportation, commerce and manufacturing, technology and engineering, travel and tourism, and geography. -

Pa-Railroad-Shops-Works.Pdf

[)-/ a special history study pennsylvania railroad shops and works altoona, pennsylvania f;/~: ltmen~on IndvJ·h·;4 I lferifa5e fJr4Je~i Pl.EASE RETURNTO: TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER DENVER SERVICE CE~TER NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ~ CROFIL -·::1 a special history study pennsylvania railroad shops and works altoona, pennsylvania by John C. Paige may 1989 AMERICA'S INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE PROJECT UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR I NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ~ CONTENTS Acknowledgements v Chapter 1 : History of the Altoona Railroad Shops 1. The Allegheny Mountains Prior to the Coming of the Pennsylvania Railroad 1 2. The Creation and Coming of the Pennsylvania Railroad 3 3. The Selection of the Townsite of Altoona 4 4. The First Pennsylvania Railroad Shops 5 5. The Development of the Altoona Railroad Shops Prior to the Civil War 7 6. The Impact of the Civil War on the Altoona Railroad Shops 9 7. The Altoona Railroad Shops After the Civil War 12 8. The Construction of the Juniata Shops 18 9. The Early 1900s and the Railroad Shops Expansion 22 1O. The Railroad Shops During and After World War I 24 11. The Impact of the Great Depression on the Railroad Shops 28 12. The Railroad Shops During World War II 33 13. Changes After World War II 35 14. The Elimination of the Older Railroad Shop Buildings in the 1960s and After 37 Chapter 2: The Products of the Altoona Railroad Shops 41 1. Railroad Cars and Iron Products from 1850 Until 1952 41 2. Locomotives from the 1860s Until the 1980s 52 3. Specialty Items 65 4. -

Resorts & Recreation

National Park Service: Resorts and Recreation RESORTS & RECREATION An Historic Theme Study of the New Jersey Heritage Trail Route RESORTS & RECREATION MENU an Historic Theme Study of the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route Contents The Atlantic Shore: Middlesex, Monmouth, Ocean, Burlington, Atlantic, and Cape May Counties Methodology Chapter 1 Early Resorts Chapter 2 Railroad Resorts Chapter 3 Religious Resorts Chapter 4 The Boardwalk Chapter 5 Roads and Roadside Attractions Chapter 6 Resort Development in the Twentieth Century Appendix A Existing Documentation Bibliography Sarah Allaback, Editor Chuck Milliken, Layout, Design, & Contributing Editor http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/nj1/index.htm[11/15/2013 2:48:32 PM] National Park Service: Resorts and Recreation 1995 The Sandy Hook Foundation, Inc. and National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route Mauricetown, New Jersey History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact Top Last Modified: Mon, Jan 10 2005 10:00:00 pm PDT http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/nj1/index.htm http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/nj1/index.htm[11/15/2013 2:48:32 PM] National Park Service: Resorts and Recreation (Table of Contents) RESORTS & RECREATION An Historic Theme Study of the New Jersey Heritage Trail Route MENU CONTENTS COVER Contents Cover photograph: Beach Avenue, Cape May, NJ. "As early as 1915, parking at beach areas was beginning to be a problem. In the background Methodology is "Pavilion No. 1' Pier. This picture was taken from the Stockton Bath House area, revealing a full spectrum of summer afternoon seaside attire." Chapter 1 Courtesy May County Historical and Genealogical Society. -

Transportation Trips, Excursions, Special Journeys, Outings, Tours, and Milestones In, To, from Or Through New Jersey

TRANSPORTATION TRIPS, EXCURSIONS, SPECIAL JOURNEYS, OUTINGS, TOURS, AND MILESTONES IN, TO, FROM OR THROUGH NEW JERSEY Bill McKelvey, Editor, Updated to Mon., Mar. 8, 2021 INTRODUCTION This is a reference work which we hope will be useful to historians and researchers. For those researchers wanting to do a deeper dive into the history of a particular event or series of events, copious resources are given for most of the fantrips, excursions, special moves, etc. in this compilation. You may find it much easier to search for the RR, event, city, etc. you are interested in than to read the entire document. We also think it will provide interesting, educational, and sometimes entertaining reading. Perhaps it will give ideas to future fantrip or excursion leaders for trips which may still be possible. In any such work like this there is always the question of what to include or exclude or where to draw the line. Our first thought was to limit this work to railfan excursions, but that soon got broadened to include rail specials for the general public and officials, special moves, trolley trips, bus outings, waterway and canal journeys, etc. The focus has been on such trips which operated within NJ; from NJ; into NJ from other states; or, passed through NJ. We have excluded regularly scheduled tourist type rides, automobile journeys, air trips, amusement park rides, etc. NOTE: Since many of the following items were taken from promotional literature we can not guarantee that each and every trip was actually operated. Early on the railways explored and promoted special journeys for the public as a way to improve their bottom line. -

Title Subject Author Publ Abbr Date Price Format Size Binding Pages

Title Subject Author Publ abbr Date Price Cond Sub title Notes ISBN Number Qty Size Pages Format Binding 100 Jahre Berner-Oberland-Bahnen; EK-Special 18 SWISS,NG Muller,Jossi EKV 1990 $24.00 V 4 SC 164 exc Die Bahnen der Jungfrauregiongerman text EKS18 1 100 Trains, 100 Years, A Century of Locomotives andphotos Trains Winkowski, SullivanCastle 2005 $20.00 V 5 HC 167 exc 0-7858-1669-0 1 100 Years of Capital Traction trolleys King Taylor 1972 $75.00 V 4 HC The329 StoryExc of Streetcars in the Nations Capital 72-97549 1 100 Years of Steam Locomotives locos Lucas Simmons-Boardman1957 $50.00 V 4 HC 278 exc plans & photos 57-12355 1 125 Jahre Brennerbahn, Part 2 AUSTRIA Ditterich HMV 1993 $24.00 V 4 T 114 NEW Eisenbahn Journal germanSpecial text,3/93 color 3-922404-33-2 1 1989 Freight Car Annual FREIGHT Casdorph SOFCH 1989 $40.00 V 4 ST 58 exc Freight Cars Journal Monograph No 11 0884-027X 1 1994-1995 Transit Fact Book transit APTA APTA 1995 $10.00 v 2 SC 174 exc 1 20th Century NYC Beebe Howell North 1970 $30.00 V 4 HC 180 Exc 0-8310-7031-5 1 20th Century Limited NYC Zimmermann MBI 2002 $34.95 V 4 HC 156 NEW 0-7603-1422-5 1 30 Years Later, The Shore Line TRACTIN Carlson CERA 1985 $60.00 V 4 ST 32 exc Evanston - Waukegan 1896-1955 0-915348-00-4 1 35 Years, A History of the Pacific Coast Chapter R&LHS PCC R&LHS PCC R&LHS 1972 V 4 ST 64 exc 1 36 Miles of Trouble VT,SHORTLINES,EASTMorse Stephen Greene1979 $10.00 v 2 sc 43 exc 0-8289-0182-1 1 3-Axle Streetcars, Volume One trolley Elsner NJI 1994 $250.00 V 4 SC 178 exc #0539 of 1000 0-934088-29-2 -

American Engineer and Railroad Journal

March, i g96 AMERICAN ENGINEER, CAR||BUILDER AND RAILROAD JOURNAL S3 The b oiler of a locomotive drawing the New York and ing a t rain of four cars which was switched by the motors Philadelphia express train on the Delaware, Lackawanna from the incoming to the outgoing tracks and up to the & Western Railroad exploded near Cassville, N. Y. , Feb. cable sheaves several times. The car made two round 18, killing both the engineer and fireman. trips over the bridge to the satisfaction of the officials pres The B rooks Locomotive .Works has an order from the ent. Northern Ohio for building six Mogul engines with 18-inch At a m eeting of the shareholders of the Mount Yamalpais by 24-inch cylinders. These engines are duplicates of those Scenic Railway Company, held early in February. Sidney MARCH. 1 896. for the Lake Erie & Western, which operates the Northern B. Cushing was elected President: David McKay, Vice- Ohio. CONTENTS. President; Louis L. Janes, Secretary, and the First National The B arney & Smith Manufacturing Company, of Day- Bank of San Francisco, Treasurer. A contract for grading Page. Page, ton. O., will built for C. J. Hamlin, of Buffalo, a private and track laying was let to the California Construction Illustrated A rticles: Editorials '. car for the transportation of racehorses. It will be 62 feet Company and work has already begun. Contracts are Twin-Hopper G ondola Car of Afn ""westingEouae'-Boyden lon8- and wi" 136 carried on six-wheeled trucks with steel- 70,000 Pounds Capacity— about to be let for engines, boilers, dynamos and other Northern Pacific Road 35 Suit.......... -

Local-Nj-Century-Plan-Report.Pdf

The Century Plan A Study of One Hundred Conservation Sites in the Barnegat Bay Watershed Researched and Written for the Trust for Public Land by Peter P. Blanchard, III, with assistance from Herpetological Associates, Inc. with assistance and editing by Andrew L. Strauss “I only went out for a walk, and finally concluded to stay out until sundown, for going out, I found, was really going in.” John Muir Table of Contents Introduction 4 Bay Island Sites 5 Coastal/Near Shore Sites 6 Pineland Sites 7 Recreation/Restoration Sites 8 Portraits of Specific Sites Bay Islands 9 - Black Whale Sedge 9 - Bonnet Island 10 - Cedar Bonnet/Northern and Southern Marshes 11 - Drag Sedge and Hester Sedge 12 - East Sedge 13 - Flat Island and Islets 14 - Ham Island and Islets 15 - Harbor Island (with Al’s Island) 16 - High Island 17 - Hither Island 18 - Little Island 19 - Little Sedge Island 20 - Lower Little Island (Post Island) 20 - Marsh-Elder Islands 21 - Middle Sedge 22 - Middle Sedge Island 23 - Mike’s Island (with Bill’s and Wilde’s Islands) 24 - Mordecai Island 25 - Northwest Point Island 26 - Parkers Island 27 - Pettit Island 28 - Sandy Island 29 - Sedge Island 30 - Shelter Island 31 - Sloop Sedge and Islet 32 - Stooling Point Island 33 - West Sedge 34 - Woods Island 35 Coastal/Near Shore 36 - Barnegat Bay Beach Inland Area 36 1 - Beaver Dam Creek/North Branch 38 - Beaver Dam Creek/South Branch 39 - Cedar Bridge Branch 40 - Cedar Creek Point/Lanoka Harbor 41 - Cedar Creek South 42 - Cedar Run Creek/East of Parkway 43 - Cedar Run Creek/Northwest Extension -

Camden & Amboy Railroad Symposium

CAMDEN & AMBOY RAILROAD SYMPOSIUM November 10, 2007 Bordentown, New jersey In Commemoration of the 175th Anniversary of the First Run of the John Bull Locomotive in Bordentown, New Jersey November 12, 1831 Presentations 8:00 - 9:00 am Registration 9:00 - 9:15 am Welcoming Remarks Mark Liss and John Kilbride 9:15 - 9:45 am Colonel John Stevens – Vision, Machine & the Family Legacy James Alexander, Jr. Jim’s presentation will explore John Stevens, the man and his legacy. Included will be discussion of Stevens’ development of steam engines and his efforts to promote railroads in NJ and elsewhere. Jim will also look at the development and operation of Stevens’ demonstration locomotive and the construction of the replica “John Stevens” locomotive. Jim Alexander is retired from New Jersey state government, and now designs web sites. He built the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania's computer network and maintains its large web site. It was there that he became interested in John Stevens' work over a decade ago. He has authored works on railroad track pans, early radio use by railroads, and turntables, including several articles in Trains magazine. 9:45 - 10:30 am Cramptons, Monsters & Bulls: Technology Transfer & Innovations on Robert L. Stevens’s Camden & Amboy Railroad, 1815-1856 Kurt R. Bell Kurt will provide a comparative technological analysis and overview of motive power development on the Camden & Amboy Railroad during its earliest years. He will also explore how the entrepre- neurship of Robert Stevens had a lasting influence on the evolution of such exotic engines as The John Bull, The Monster, and the Cramptons, which represented the ancestors of what later evolved into the standardization of Pennsylvania Railroad steam locomotive design. -

Decoy & Gunning Show

Free Admission • Free Shuttle Bus Service FREE SEEPARKING PAGES 6 & 7 34TH ANNUAL OCEAN COUNTY Decoy & Gunning Show Dock Dog Competition As featured on ESPN September 24th & 25th, 2016 7am - 5pm Saturday, 7am - 4pm Sunday In Historic Tuckerton, NJ Over 300 Waterfowling Exhibitors & Vendors TWO SEPARATE LOCATIONS BOTH CONVENIENTLY ACCESSIBLE BY FREE SHUTTLE BUS SERVICE Tip Seaman County Park • Tuckerton Seaport For More Information Call (609) 971-3085 www.oceancountyparks.org Ocean County Board Various Hunting Supplies, of Chosen Freeholders John C. Bartlett, Jr. Displays, Contests, Music Chairman of Parks & Recreation Food, Antique Collectible John P. Kelly • Virginia E. Haines Gerry P. Little • Joseph H. Vicari Decoys and so much more! CelebrateCelebrate Traditional TTrradit ional ArtsArts at the SeaportSeaport HeritageHeritage TentTTeent Meet arartiststists fromfrom the JerseyJersey SShorehore FFolklifFolklifeolkliffee Center:CCenter: Basketmakers,makers,, DecoyDecDecoy Carvers,Carvers,, QuiltersQuilters and MorMore!e! See the traditionaltrraaditional arartsts off South JerseyJerseeyy at TTipip SeSeaman CountCountynttyy PParPark.arrkk. Sponsorreded bby: Prresentedesenteesented by: JerseyShoreFolklifeCenter at Tuckerton Seaport www.TTucuckertonSeapuckertonSeaport.or g Welcome! AT THE SHOW Contests TO THE 34TH ANNUAL Skeet Shooting, Duck Calling, Retrieving and Decoy Carving, OCEAN COUNTY DECOY & GUNNING SHOW! Art and Photo The Ocean County Board of Chosen For music lovers, some of the most Freeholders and the Ocean County famous Pine Barrens bands and Department of Parks & Recreation soloists will grace us with their musi- Exhibitors would like to welcome you to the cal talents. Decoys, Boat Builders, 2016 Ocean County Decoy & Gunning More than 50 contests and seminars Wildlife Art, Antiques, Show. will be held at the show sites during Sportsmen’s Supplies Every year the show has gotten bigger two action-packed days. -

Download a Transcript of the Video

OurStory Video: John Bull Riding the Rails Date: November 2010 http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/v/johnbull.html Codes: JW = Jenny Wei N = Narrator “ “ =interrupting, pause [ ] = not speaker’s words ********************************************************************************************************* JW: Hi, I’m Jenny and I’m an Education Specialist here at the National Museum of American History. The object behind me is a steam locomotive called the John Bull. A locomotive is an engine that can pull other things behind it, such as train cars. In 1981, for the John Bull’s 150th birthday, the Museum took the train out to run on nearby train tracks. Take a look at this video to see the John Bull locomotive in action. Video transcript: [on screen text] The Smithsonian Institution presents the John Bull [on screen text] The World’s Oldest Operable Locomotive N: Among the engines of change is the locomotive. With its speed, its power, its transforming effect in bringing new civilization into the wilderness, the locomotive became a symbol of the Industrial Revolution. This locomotive, called the John Bull, was made in England. Americans imported it in 1831 for use between Philadelphia and New York City on one of the first railway routes in the United States. N: The John Bull was shipped to an America where the Industrial Revolution was just beginning. The man who assembled the locomotive after its arrival had never seen one. The people who rode in the cars it pulled had never moved so fast. Americans adapted quickly to the new machine and then changed the machine to better serve a rapidly expanding society. -

Edward H. Weber Collection of Railroad Timetables 2573

Edward H. Weber collection of railroad timetables 2573 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Manuscripts and Archives PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Edward H. Weber collection of railroad timetables 2573 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................. 11 Biographical Note ........................................................................................................................................ 11 Scope and Content ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................... 13 Related Materials ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Controlled Access Headings ........................................................................................................................ 15 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................... 15 Public timetables - Amtrak ......................................................................................................................