A Long and Dutiful Life – the Story of B&O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

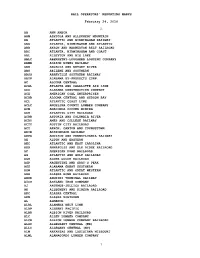

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 a AA

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 A AA ANN ARBOR AAM ASHTOLA AND ALLEGHENY MOUNTAIN AB ATLANTIC AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY ABA ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND ATLANTIC ABB AKRON AND BARBERTON BELT RAILROAD ABC ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND COAST ABL ALLEYTON AND BIG LAKE ABLC ABERNETHY-LOUGHEED LOGGING COMPANY ABMR ALBION MINES RAILWAY ABR ARCADIA AND BETSEY RIVER ABS ABILENE AND SOUTHERN ABSO ABBEVILLE SOUTHERN RAILWAY ABYP ALABAMA BY-PRODUCTS CORP. AC ALGOMA CENTRAL ACAL ATLANTA AND CHARLOTTE AIR LINE ACC ALABAMA CONSTRUCTION COMPANY ACE AMERICAN COAL ENTERPRISES ACHB ALGOMA CENTRAL AND HUDSON BAY ACL ATLANTIC COAST LINE ACLC ANGELINA COUNTY LUMBER COMPANY ACM ANACONDA COPPER MINING ACR ATLANTIC CITY RAILROAD ACRR ASTORIA AND COLUMBIA RIVER ACRY AMES AND COLLEGE RAILWAY ACTY AUSTIN CITY RAILROAD ACY AKRON, CANTON AND YOUNGSTOWN ADIR ADIRONDACK RAILWAY ADPA ADDISON AND PENNSYLVANIA RAILWAY AE ALTON AND EASTERN AEC ATLANTIC AND EAST CAROLINA AER ANNAPOLIS AND ELK RIDGE RAILROAD AF AMERICAN FORK RAILROAD AG ATLANTIC AND GULF RAILROAD AGR ALDER GULCH RAILROAD AGP ARGENTINE AND GRAY'S PEAK AGS ALABAMA GREAT SOUTHERN AGW ATLANTIC AND GREAT WESTERN AHR ALASKA HOME RAILROAD AHUK AHUKINI TERMINAL RAILWAY AICO ASHLAND IRON COMPANY AJ ARTEMUS-JELLICO RAILROAD AK ALLEGHENY AND KINZUA RAILROAD AKC ALASKA CENTRAL AKN ALASKA NORTHERN AL ALMANOR ALBL ALAMEDA BELT LINE ALBP ALBERNI PACIFIC ALBR ALBION RIVER RAILROAD ALC ALLEN LUMBER COMPANY ALCR ALBION LUMBER COMPANY RAILROAD ALGC ALLEGHANY CENTRAL (MD) ALLC ALLEGANY CENTRAL (NY) ALM ARKANSAS AND LOUISIANA -

Jay T. Last Collection of American Transportation Prints: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pk0h51 Online items available Jay T. Last Collection of American Transportation Prints: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Diann Benti. Rare Books Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: 626-405-3473 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2013 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Jay T. Last Collection of American priJLC_TRAN 1 Transportation Prints: Finding Aid Descriptive Summary Title: Jay T. Last Collection of American Transportation Prints Dates (inclusive): approximately 1833-approximately 1911 Bulk dates: 1840-1900 Collection Number: priJLC_TRAN Collector: Last, Jay T. Extent: approximately 167 items Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens: Rare Books Department Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: 626-405-3473 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The prints in the Jay T. Last Collection of American Transportation consist of over 160 prints related to land-based modes of transportation primarily in the United States. The collection dates from the 1830s into the early 20th century and consists largely of materials pertaining to railroads, with additional items concerning the bicycle and carriage, coach, and wagon industries. Item types include advertising cards, posters, broadsides, maps, timetables, views, and other visual materials primarily produced by transportation-affiliated entities such as railroad companies and vehicle and parts manufacturers. The collection features lithographs produced by American artists, printers, and publishers, as well as engravings, letterpress and woodblock prints. Topical subjects include transportation, commerce and manufacturing, technology and engineering, travel and tourism, and geography. -

HO-Scale #562 in HO-Scale – Page 35 by Thomas Lange Page 35

st 1 Quarter 2021 Volume 11 Number 1 _____________________________ On the Cover of This Issue Table Of Contents Thomas Lange Models a NYC Des-3 Modeling A NYC DES-3 in HO-Scale #562 In HO-Scale – Page 35 By Thomas Lange Page 35 Modeling The Glass Train By Dave J. Ross Page 39 A Small Midwestern Town Along A NYC Branchline By Chuck Beargie Page 44 Upgrading A Walthers Mainline Observation Car Rich Stoving Shares Photos Of His By John Fiscella Page 52 Modeling - Page 78 From Metal to Paper – Blending Buildings on the Water Level Route By Bob Shaw Page 63 Upgrading A Bowser HO-Scale K-11 By Doug Kisala Page70 Kitbashing NYCS Lots 757-S & 766-S Stockcars By Dave Mackay Page 85 Modeling NYC “Bracket Post” Signals in HO-Scale By Steve Lasher Page 89 Celebrating 50 Years as the Primer Railroad Historical Society NYCentral Modeler From the Cab 5 Extra Board 8 What’s New 17 The NYCentral Modeler focuses on providing information NYCSHS RPO 23 about modeling of the railroad in all scales. This issue NYCSHS Models 78 features articles, photos, and reviews of NYC-related Observation Car 100 models and layouts. The objective of the publication is to help members improve their ability to model the New York Central and promote modeling interests. Contact us about doing an article for us. [email protected] NYCentral Modeler 1st Qtr. 2021 2 New York Central System Historical Society The New York Central System Central Headlight, the official Historical Society (NYCSHS) was publication of the NYCSHS. -

Title Subject Author Publ Abbr Date Price Format Size Binding Pages

Title Subject Author Publ abbr Date Price Cond Sub title Notes ISBN Number Qty Size Pages Format Binding 100 Jahre Berner-Oberland-Bahnen; EK-Special 18 SWISS,NG Muller,Jossi EKV 1990 $24.00 V 4 SC 164 exc Die Bahnen der Jungfrauregiongerman text EKS18 1 100 Trains, 100 Years, A Century of Locomotives andphotos Trains Winkowski, SullivanCastle 2005 $20.00 V 5 HC 167 exc 0-7858-1669-0 1 100 Years of Capital Traction trolleys King Taylor 1972 $75.00 V 4 HC The329 StoryExc of Streetcars in the Nations Capital 72-97549 1 100 Years of Steam Locomotives locos Lucas Simmons-Boardman1957 $50.00 V 4 HC 278 exc plans & photos 57-12355 1 125 Jahre Brennerbahn, Part 2 AUSTRIA Ditterich HMV 1993 $24.00 V 4 T 114 NEW Eisenbahn Journal germanSpecial text,3/93 color 3-922404-33-2 1 1989 Freight Car Annual FREIGHT Casdorph SOFCH 1989 $40.00 V 4 ST 58 exc Freight Cars Journal Monograph No 11 0884-027X 1 1994-1995 Transit Fact Book transit APTA APTA 1995 $10.00 v 2 SC 174 exc 1 20th Century NYC Beebe Howell North 1970 $30.00 V 4 HC 180 Exc 0-8310-7031-5 1 20th Century Limited NYC Zimmermann MBI 2002 $34.95 V 4 HC 156 NEW 0-7603-1422-5 1 30 Years Later, The Shore Line TRACTIN Carlson CERA 1985 $60.00 V 4 ST 32 exc Evanston - Waukegan 1896-1955 0-915348-00-4 1 35 Years, A History of the Pacific Coast Chapter R&LHS PCC R&LHS PCC R&LHS 1972 V 4 ST 64 exc 1 36 Miles of Trouble VT,SHORTLINES,EASTMorse Stephen Greene1979 $10.00 v 2 sc 43 exc 0-8289-0182-1 1 3-Axle Streetcars, Volume One trolley Elsner NJI 1994 $250.00 V 4 SC 178 exc #0539 of 1000 0-934088-29-2 -

NYCSHS Modeler's E-Zine

st NYCSHS Modeler’s E-zine 1 Quarter 2014 Vol. 4 Number 1 An added focus for the Society on NYC Modeling Table of Contents NYC Models of Don Wetzel 1 & 18 By Noel Widdifield The NYC Piney Fork Branch 22 Railroad By Seth Gartner NYC Battery Houses from the 38 Engineering Dept. By Manuel Duran-Duran Modeling NYC Battery Houses 44 From the Harmon Files Seth Gartner’s Piney Fork Branch railroad is set in By Larry Faulkner Minerva, OH and has been a 12-year project. It is not NYC Modeling in S-scale 51 your typical four-track main. (Page 22) By Dick Karnes The Paint Code Triangle 61 Check out the regular NYCentral Modeler feature, “From The New By Peter Weiglin York Central Engineering Department” by Manuel Duran-Duran. It offers scale drawings of NYCS structures that you can model. Preparing the Basement 64 By Pete LaGuarda The NYCentral Modeler focuses on providing information31 about modeling of the railroad in all scales. This issue NYCRR’s West Side Freight 71 features articles, photos, and reviews of NYC-related Lines - Part 3 By Ron Parisi models and layouts. The objective for the publication is to help members improve their ability to model the New The NYCSHS provides considerable York Central and promote modeling interests. NYC Railroad information that is very useful for modelers. Pages 2 & 4. The NYC Models of Don Wetzel We contacted Don Wetzel, the engineer on the famous NYC M-497 that set a World Speed Record on July 23, 1966. I was curious to see if Don was a NYC modeler. -

In This Issue of Scale Rails, the NMRA Is Pleased to Announce the Debut of a Series of New Or Revised Data Sheets

Diesel Locomotive 1 Researcher: Jerry T Moyers ALCO HH–SERIES Switchers Manufacturer: ALCO Photography and captions: Louis A Marre Collection Date Built: 1931–1940 Horsepower: 600-1000 Drawings: Stephen M. Priest, MMR In this issue of Scale Rails, the NMRA is pleased to announce the debut of a series of new or revised Data Sheets. The initial Data Sheets, covering early American Locomotive Co. (Alco) diesel-electric switching locomo- tives, are the work of noted diesel authority and modeler Jerry T. Moyers. Jerry’s highly Top left: Boston & Maine Phase 1 detailed diesel drawings have appeared in 1102 is ex-Alco demonstrator 602, Railroad Model Craftsman, and he has also with the cab as front, shown at work in Boston on September 1, 1951. This worked closely with a number of manufactur- unit dates from May 1934 as Alco 602. ers and importers to improve the accuracy of B&M also purchased a stock unit and numbered it 1101. Note that B&M their products. “reversed” the controls and now the Noted author Louis A. Marre has pro- long end is marked as F-1 for front end, No. 1 side. vided the reader with detailed captions to augment his choice of the quaity photographic Bottom left: Lackawanna bought Phase 1 examples of the earliest high doumentation included in the Data Sheets. hood configuration, oriented with the The Data Sheets will include prototype cab as front. Lackawanna 323 is seen here at the end of a long career. Its information about a specific manufacturer, bell has been removed from the sim- specifications for the particular locomotive(s) ple bracket next to the headlight, but otherwise it is intact after 30 years Above: Many high hood purchasers were interested in diesels Below: Peoria & Pekin Union 100 Phase 2, its first diesel, featured, and an in-depth discussion of mod- of hard service. -

American Engineer and Railroad Journal

March, i g96 AMERICAN ENGINEER, CAR||BUILDER AND RAILROAD JOURNAL S3 The b oiler of a locomotive drawing the New York and ing a t rain of four cars which was switched by the motors Philadelphia express train on the Delaware, Lackawanna from the incoming to the outgoing tracks and up to the & Western Railroad exploded near Cassville, N. Y. , Feb. cable sheaves several times. The car made two round 18, killing both the engineer and fireman. trips over the bridge to the satisfaction of the officials pres The B rooks Locomotive .Works has an order from the ent. Northern Ohio for building six Mogul engines with 18-inch At a m eeting of the shareholders of the Mount Yamalpais by 24-inch cylinders. These engines are duplicates of those Scenic Railway Company, held early in February. Sidney MARCH. 1 896. for the Lake Erie & Western, which operates the Northern B. Cushing was elected President: David McKay, Vice- Ohio. CONTENTS. President; Louis L. Janes, Secretary, and the First National The B arney & Smith Manufacturing Company, of Day- Bank of San Francisco, Treasurer. A contract for grading Page. Page, ton. O., will built for C. J. Hamlin, of Buffalo, a private and track laying was let to the California Construction Illustrated A rticles: Editorials '. car for the transportation of racehorses. It will be 62 feet Company and work has already begun. Contracts are Twin-Hopper G ondola Car of Afn ""westingEouae'-Boyden lon8- and wi" 136 carried on six-wheeled trucks with steel- 70,000 Pounds Capacity— about to be let for engines, boilers, dynamos and other Northern Pacific Road 35 Suit.......... -

August, 1974 Ne "

T E AUGUST, 1974 NE " ... the intent behind the creation of our department was to provide greater coordination and assistance in the planning activities in all The departments." Corporate Planning Department G. A. Kellow Vice President- Corporate Planning In an article which appeared previously in this maga ditions. In a very real sense, planning involves a delicate zine, President Smith stated what he considered to be balance between short term commitments and long term the most important objectives of the Milwaukee Road. flexibility. These objectives bear repeating. They are: There are several types of planning. COMPREHEN 1) Provide the level and quality of total service nec SIVE planning involves the constant formulation of ob essary to retain existing positions in transportation mar jectives and the guidance of the company's activities kets and provide a base to profitably expand the railroad's toward their attainment. Comprehensive planning calls participation in existing and in new markets. for a total evaluation of the company's operations as well 2) Maximize utilization of assets, eliminating those as its potential. This kind of overview is one of the areas not required for present and future needs, and concen in which the corporate planning staff can play an im trating available resources toward activities that have portant role. present and future strategic purpose. A second type of planning, called FUNCTIONAL, 3) Establish and maintain a responsibility budgeting has to do with the individual elements of a total problem. and control system encompassing all departments and Functional planning focuses on how each part can best subsidiaries to provide proper control of all activities. -

NASG S Scale Magazine Index PDF Report

NASG S Scale Magazine Index PDF Report Bldg Article Title Author(s) Scale Page Mgazine Vol Iss Month Yea Dwg Plans "1935 Ridgeway B6" - A Fantasy Crawler in 1:24 Scale Bill Borgen 80 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Mar - Apr 2004 "50th Anniversary of S" - 1987 NASG Convention Observations Bob Jackson S 6 Dispatch Dec 1987 "Almost Painless" Cedar Shingles Charles Goodrich 72 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Mar - Apr 1994 "Baby Gauge" in the West - An Album of 20-Inch Railroads Mallory Hope Ferrell 47 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Jul - Aug 1998 "Bashing" a Bachmann On30 Gondola into a Quincy & Torch Lake Rock Car Gary Bothe On30 67 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Jul - Aug 2014 "Been There - Done That" (The Personal Journey of Building a Model Railroad) Lex A. Parker On3 26 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Mar - Apr 1996 "Boomer" CRS Trust "E" (D&RG) Narrow Gauge Stock Car #5323 -Drawings Robert Stears 50 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz May - Jun 2019 "Brakeman Bill" used AF trains on show C. C. Hutchinson S 35 S Gaugian Sep - Oct 1987 "Cast-Based" Rock Work Phil Hodges 34 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Nov - Dec 1991 "Causey's Coach" Mallory Hope Ferrell 53 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Sep - Oct 2013 "Chama," The PBL Display Layout Bill Peter, Dick Karnes S 26 3/16 'S'cale Railroading 2 1 Oct 1990 "Channel Lock" Bench Work Ty G. Treterlaar 59 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Mar - Apr 2001 "Clinic in a Bag" S 24 S Gaugian Jan - Feb 1996 "Creating" D&RGW C-19 #341 in On3 - Some Tips Glenn Farley On3 20 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Jan - Feb 2010 "Dirting-In" -

Scale Trains

Celebrating Scale the art of MAGAZINE Trains 1:48 modeling O u July/August 2009 Issue #45 US $6.95 • Can $8.95 Display until August 31, 2009 Celebrating the art of 1:48 modeling Issue #45 Scale July/August 2009 Vol. 8 - No.4 Editor-in-Chief/Publisher Joe Giannovario Trains MAGAZINE [email protected] O Features Art Director Jaini Giannovario [email protected] 4 The Aspen & Western Ry — Red Wittman An On30 layout with many scratchbuilt structures. Managing Editor 12 Chicago March Meet Contest Photos Mike Cougill Part 2 of our contest coverage. [email protected] 15 A New Roundhouse for the Clover Leaf — Warner Clark Building a roundhouse, even to P48 specs, isn’t that difficult. Advertising Manager Jeb Kriigel 21 Greg Heier 1941 - 2009 [email protected] O Scale News editor passes away in April. Customer 23 Detailing Die-Cast Locomotives Part 2 — Joe Giannovario Service Redetailing the tender required the kindness of friends. Spike Beagle 29 Installing Lighted Train Indicators — Charles Morrill Complaints Add this slick detail to your SP and UP locomotives. L’il Bear 31 Modeler’s Trick — Bill Davis CONTRIBUTORS Here’s an inexpensive way to sort and store your strip stock. TED BYRNE GENE CLEMENTS CAREY HINch ROGER C. PARKER 34 Atlas Postwar AAR Boxcar Upgrade — Larry Kline Improve and refine the details of this commonly found model. Subscription Rates: 6 issues 38 A Home Built Rivet Embosser — John Gizzi US - Periodical Class Delivery US$35 US - First Class Delivery (1 year only) US$45 If necessity is the Mother of Invention, then frugality is its Father. -

S & W Parts Supply 762 Whitney Drive Niskayuna, NY 12309-3018 Parts

S & W Parts Supply Parts List [email protected] 762 Whitney Drive www.SandWparts.com Niskayuna, NY 12309-3018 10 Digit (518) 280-5197 Stock Number Item Description Price 6000002111 Lock Washer #6 $ 0.30 6000024004 Aux. Rail Clip $ 1.00 6000037014 Rivet .086x.158x.188 $ 0.35 6000041055 Ground Spring $ 1.25 6000041065 Side Rail/Blk $ 3.75 6000050060 Brush Connector $ 1.00 6000051060 End Railing $ 6.00 6000052013 Hose Nozzle $ 1.00 6000055028 Coupler/Dummy $ 3.00 6000058005 Pulley/Rotary Plow $ 3.00 6000058006 Pulley Shft.125x.935 $ 1.00 6000058008 End Rail/Rotary Plow $ 5.00 6000058021 Brush Plate $ 6.00 6000058024 Armature Shft W/Worm $ 3.60 6000058107 Washer/Thrust $ 0.50 6000065024 Collector Spring $ 0.30 6000065043 Tir/.470x.036x.116 $ 1.50 6000065043 Traction Tire $ 1.50 6000065209 Worm Gear $ 3.00 6000068005 Light Socket $ 4.00 6000068041 Worm Wheel $ 10.00 6000075008 Socket Housing $ 1.00 6000075014 Lamp Shade/Blk $ 1.25 6000078008 Lamp Housing $ 1.00 6000089006 Hedges $ 1.00 6000101002 E-Unit/Isspectioncar $ 25.00 6000132016 Glass/Large Door $ 1.00 6000132023 Stud/Brace Mount $ 0.75 6000140008 Lamp Contact $ 0.55 6000140009 Washer/.102x.264x.03 $ 0.50 6000140010 Insulator $ 0.50 6000140016 Rivet/.088x.134x.120 $ 0.40 6000140019 Coil Assy/Banjo $ 9.10 6000140022 Washer/Nylon $ 0.45 6000140023 Fiber Washer $ 0.45 6000140024 Washer $ 0.45 6000140028 Rot.Cup & Pin Assy $ 5.00 6000140030 Pivot Pin $ 1.00 6000140032 Drive Washer/Banjo $ 1.25 6000140052 Insulator Plate $ 0.50 6000145024 Door Glass/Gateman $ 0.85 6000160002 Dump Tray $ 2.50 All prices subject to change without notice. -

HO-Scale NYC 19000 Caboose (Trueline Trains) Pre-Order Only

4th Quarter 2015 NYCSHS Modeler’s E-zine Volume 5 Number 4 An added focus for the Society on NYC Modeling Table of Contents Bob Shaw & Fabian Beltran Model Old Dog New Trick = Lord of the Resin By Phil Darkins the NYC in 3-Rail O-Gauge 34 NYC’s 50’ PS-1 Boxcar – Part 1 By Seth Lakin 56 The Early Car Shop NYC&HR 35’ Standard Boxcar By Kyle Coble 60 Building an O-Scale NYC Water Level Route By Bob Shaw & Fabian Beltran Bob Shaw tells us that layout changes are 71 inevitable . Page 71. Building the Rexall Train Loco in ¾”-Scale Steve Bratina Builds Another ¾”- By Steve Bratina 91 Scale Live Steamer Modeling Cross-River/Lake Transfer Systems By George Reineke 101 From the Cab 6 Extra Board 7 What’s New 10 Steve’s Rexall Train Mohawk locomotive is shown NYCSHS RPO 22 here with primer applied. Page 91. The Observation Car 114 Cover photo is George Reineke’s layout. The NYCentral Modeler The NYCentral Modeler focuses on providing information about modeling of the railroad in all scales. This issue features articles, photos, and reviews of NYC-related models and layouts. The objective for the publication is to help members improve their ability to model the New York Central and promote modeling interests. Contact us about doing an article for us. mailto:[email protected] NYCentral Modeler 4th Quarter 2015 2 New York Central System Historical Society The New York Central System Central Headlight, the official Historical Society (NYCSHS) was publication of the NYCSHS. organized in March 1970 by the The Central Headlight is only combined efforts of several available to members, and former employees of the New each issue contains a wealth Board of Directors York Central Railroad.