The Last of Old Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fishers and Fish Traders of Lake Victoria: Colonial

FISHERS AND FISH TRADERS OF LAKE VICTORIA: COLONIAL POLICY AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF FISH PRODUCTION IN KENYA, 1880-1978. by PAUL ABIERO OPONDO Student No. 34872086 submitted in accordance with the requirement for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: DR. MUCHAPARARA MUSEMWA, University of the Witwatersrand CO-PROMOTER: PROF. LANCE SITTERT, University of Cape Town 10 February 2011 DECLARATION I declare that ‘Fishers and Fish Traders of Lake Victoria: Colonial Policy and the Development of Fish Production in Kenya, 1895-1978 ’ is my original unaided work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. I further declare that the thesis has never been submitted before for examination for any degree in any other university. Paul Abiero Opondo __________________ _ . 2 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to several fishers and fish traders who continue to wallow in poverty and hopelessness despite their daily fishing voyages, whose sweat and profits end up in the pockets of big fish dealers and agents from Nairobi. It is equally dedicated to my late father, Michael, and mother, Consolata, who guided me with their wisdom early enough. In addition I dedicate it to my loving wife, Millicent who withstood the loneliness caused by my occasional absence from home, and to our children, Nancy, Michael, Bivinz and Barrack for whom all this is done. 3 ABSTRACT The developemnt of fisheries in Lake Victoria is faced with a myriad challenges including overfishing, environmental destruction, disappearance of certain indigenous species and pollution. -

The Luo People in South Sudan

The Luo People in South Sudan The Luo People in South Sudan: Ethnological Heredities of East Africa By Kon K. Madut The Luo People in South Sudan: Ethnological Heredities of East Africa By Kon K. Madut This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Kon K. Madut All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5743-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5743-7 I would like to dedicate this book to all the Luo People in South Sudan, Ethiopia, Congo, Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania TABLE OF CONTENTS Author Biography ...................................................................................... ix About this Edition ...................................................................................... xi Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xiii Chapter One ................................................................................................ 1 The Context Background Theoretical Framework Investigating Luo Groups The Construction of Ethnicity and Language Chapter Two ............................................................................................ -

Baudelaire 525 Released Under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial Licence

Table des matières Préface i Préface des Fleurs . i Projet de préface pour Les Fleurs du Mal . iii Preface vi Preface to the Flowers . vi III . vii Project on a preface to the Flowers of Evil . viii Préface à cette édition xi L’édition de 1857 . xi L’édition de 1861 . xii “Les Épaves” 1866 . xii L’édition de 1868 . xii Preface to this edition xiv About 1857 version . xiv About 1861 version . xv About 1866 “Les Épaves” . xv About 1868 version . xv Dédicace – Dedication 1 Au Lecteur – To the Reader 2 Spleen et idéal / Spleen and Ideal 9 Bénédiction – Benediction 11 L’Albatros – The Albatross (1861) 19 Élévation – Elevation 22 Correspondances – Correspondences 25 J’aime le souvenir de ces époques nues – I Love to Think of Those Naked Epochs 27 Les Phares – The Beacons 31 La Muse malade – The Sick Muse 35 La Muse vénale – The Venal Muse 37 Le Mauvais Moine – The Bad Monk 39 L’Ennemi – The Enemy 41 Le Guignon – Bad Luck 43 La Vie antérieure – Former Life 45 Bohémiens en voyage - Traveling Gypsies 47 L’Homme et la mer – Man and the Sea 49 Don Juan aux enfers – Don Juan in Hell 51 À Théodore de Banville – To Théodore de Banville (1868) 55 Châtiment de l’Orgueil – Punishment of Pride 57 La Beauté – Beauty 60 L’Idéal – The Ideal 62 La Géante – The Giantess 64 Les Bijoux – The Jewels (1857) 66 Le Masque – The Mask (1861) 69 Hymne à la Beauté – Hymn to Beauty (1861) 73 Parfum exotique – Exotic Perfume 76 La Chevelure – Hair (1861) 78 Je t’adore à l’égal de la voûte nocturne – I Adore You as Much as the Nocturnal Vault.. -

Issue 13: Turn On, Tune In

The broken C I Plug in2 the electric word The kid played the silence Good morning, Vancouver! T Y Blow, Coltrane, blow Traf�ic jams: bane of the touring band We play song after song for the people stuck in their cars, the girls in the bikinis come out, and a few others too. Soon we’re playing to more people than we would’ve played to in whatever basement Dom had booked anyway. Kristie hustles shirts, hoodies and all the other junk Dom spent his tax return on. Lighters, cell phones and headlights illuminate the van and it’s almost like we’re back on stage. Just almost, underneath the stars of whatever state we’re in. Turn on, t une in The day is graycast and overshadowing. I’m jackjilling it to work, shuf�le skipping through random play, high and undecided. I see the cop out of the corner of my eye and, like a middle school novice, I double take him. “Alotta music ya got there on that thing. How much?” “It’s just a few thousand songs, man. Personal use.” “I got two CDs in my car, son. Lee Greenwood and Alan Jackson. But you wouldn’t know anything about that, would you?” 13 Winter 2013 ISSN 1916-3304 The broken C I W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 Issue 13 T Y The Broken City C o v e r Te x t , ISSN 1916-3304, is published semiannually out of Toronto, Canada, appearing sporadically in print, but The Broken City The upper excerpt is taken from Kendall Sharpe’s “On The always at: www.thebrokencitymag.com. -

Tsr6903.Mu7.Ghotmu.C

[ Official Game Accessory Gamer's Handbook of the Volume 7 Contents Arcanna ................................3 Puck .............. ....................69 Cable ........... .... ....................5 Quantum ...............................71 Calypso .................................7 Rage ..................................73 Crimson and the Raven . ..................9 Red Wolf ...............................75 Crossbones ............................ 11 Rintrah .............. ..................77 Dane, Lorna ............. ...............13 Sefton, Amanda .........................79 Doctor Spectrum ........................15 Sersi ..................................81 Force ................................. 17 Set ................. ...................83 Gambit ................................21 Shadowmasters .... ... ..................85 Ghost Rider ............................23 Sif .................. ..................87 Great Lakes Avengers ....... .............25 Skinhead ...............................89 Guardians of the Galaxy . .................27 Solo ...................................91 Hodge, Cameron ........................33 Spider-Slayers .......... ................93 Kaluu ....... ............. ..............35 Stellaris ................................99 Kid Nova ................... ............37 Stygorr ...............................10 1 Knight and Fogg .........................39 Styx and Stone .........................10 3 Madame Web ...........................41 Sundragon ................... .........10 5 Marvel Boy .............................43 -

A Conversation with Dance History: Movement And

A CONVERSATION WITH DANCE HISTORY: MOVEMENT AND MEANING IN THE CULTURAL BODY A Dissertation Submitted to The Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Seónagh Odhiambo January, 2009 © by Seónagh Odhiambo 2009 All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT A Conversation with Dance History: Movement and Meaning in the Cultural Body Seónagh Odhiambo Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2009 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Dr. Kariamu Welsh This study regards the problem of a binary in dance discursive practices, seen in how “world dance” is separated from European concert dance. A close look at 1930s Kenya Luo women’s dance in the context of “dance history” raises questions about which dances matter, who counts as a dancer, and how dance is defined. When discursive practices are considered in light of multicultural demographic trends and globalisation the problem points toward a crisis of reason in western discourse about how historical origins and “the body” have been theorised: within a western philosophical tradition the body and experience are negated as a basis for theorising. Therefore, historical models and theories about race and gender often relate binary thinking whereby the body is theorised as text and history is understood as a linear narrative. An alternative theoretical model is established wherein dancers’ processes of embodying historical meaning provide one of five bases through which to theorise. The central research questions this study poses and attempts to answer are: how can I illuminate a view of dance that is transhistorical and transnational? How can I write about 1930s Luo women in a way that does not create a case study to exist outside of dance history? Research methods challenge historical materialist frameworks for discussions of the body and suggest insight can be gained into how historical narratives operate with coercive power—both in past and present—by examining how meaning is conceptualised and experienced. -

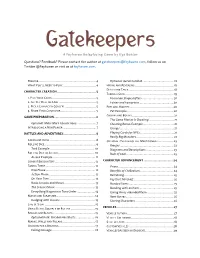

A Feyhaven Roleplaying Game by Ilya Bossov Questions?

Gatekeepers A Feyhaven Roleplaying Game by Ilya Bossov Questions? Feedback? Please contact the author at [email protected], follow us on Twitter @Feyhaven or visit us at feyhaven.com. PREMISE ...................................................................... 4 Optional: Aerial Combat ...................................... 18 WHAT YOU’LL NEED TO PLAY ......................................... 4 HIDING AND REVEALING ............................................... 18 DEATH AND TAXES ...................................................... 18 CHARACTER CREATION ............................................... 5 TAKING A GEAS ........................................................... 19 1. PICK YOUR CARDS ..................................................... 5 Fomorian Shapeshifters ...................................... 20 2. GET FEY DUST OR LOOT ............................................. 5 Fairies and Fomorians ......................................... 20 3. PICK A CHARACTER CONCEPT ...................................... 5 PETS AND MOUNTS ..................................................... 20 4. NAME YOUR CHARACTER ........................................... 5 Pet Example ........................................................ 20 GROUPS AND BOSSES .................................................. 21 GAME PREPARATION ................................................... 6 The Game Master Is Cheating! .............................. 21 Optional: Make More Connections........................ 7 Cheating Bonus Example ..................................... -

Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin This Book Is a Product of the CODESRIA Comparative Research Network

Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin This book is a product of the CODESRIA Comparative Research Network. Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin Edited by Mzime Ndebele-Murisa Ismael Aaron Kimirei Chipo Plaxedes Mubaya Taurai Bere Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa DAKAR © CODESRIA 2020 Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop, Angle Canal IV BP 3304 Dakar, 18524, Senegal Website: www.codesria.org ISBN: 978-2-86978-713-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission from CODESRIA. Typesetting: CODESRIA Graphics and Cover Design: Masumbuko Semba Distributed in Africa by CODESRIA Distributed elsewhere by African Books Collective, Oxford, UK Website: www.africanbookscollective.com The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) is an independent organisation whose principal objectives are to facilitate research, promote research-based publishing and create multiple forums for critical thinking and exchange of views among African researchers. All these are aimed at reducing the fragmentation of research in the continent through the creation of thematic research networks that cut across linguistic and regional boundaries. CODESRIA publishes Africa Development, the longest standing Africa based social science journal; Afrika Zamani, a journal of history; the African Sociological Review; Africa Review of Books and the Journal of Higher Education in Africa. The Council also co- publishes Identity, Culture and Politics: An Afro-Asian Dialogue; and the Afro-Arab Selections for Social Sciences. -

February, 1950

P.ENNSiWM J '•m: % *&i ^r^rwnrm** wmm, /A IAL STATE PUBLICATION OFFICIAL STATE PUBLICATION VOL. XIX—No. 2 FEBRUARY, 1950 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE PENNSYLVANIA FISH COMMISSION D it. ivjsion o HON. JAMES H. DUFF, Governor PUBLICITY and PUBLIC RELATIONS J. Allen Barrett Director PENNSYLVANIA FISH COMMISSION MILTON L. PEEK, President RADNOR PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER BERNARD S. HORNE, Vice-President South Office Building, Harrisburg, Pa. PITTSBURGH WILLIAM D. BURK MELROSE PARK 10 Cents a Copy—50 Cents a Year GEN. A. H. STACKPOLE DAUPHIN Subscriptions should be addressed to the Editor, PENNSYL VANIA ANGLER, South Office Building, Harrisburg, Pa. Submit p PAUL F. BITTENBENDER fee either by check or money order payable to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Stamps not acceptable. Individuals sending cash WILKES-BARRE do so at their own risk. CLIFFORD J. WELSH ERIE PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER welcomes contributions and photos of catches from its readers. Proper credit will be given to con LOUIS S. WINNER tributors. Send manuscripts and photos direct to the Editor LOCK HAVEN PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER, South Office Building, Harrisburg, Pa. S * EXECUTIVE OFFICE Entered as Second Class matter at the Post Office of Harris- 1/ burg, Pa., under act of March 3, 173. C. A. FRENCH, Executive Director ELLWOOD CITY IMPORTANT! H. R. STACKHOUSE The ANGLER should be notified immediately of change in sub Adm. Secretary scriber's address. Send both old and new addresses to Pennsyl vania Fish Commission, South Office Building, Harrisburg, Pa. * Permission to reprint will be granted if proper credit is given. C. R. BULLER Chief Fish Culturist THOMAS F. O'HARA Construction Engineer Publication Office: Tele graph Press, Cameron and WILLIAM W. -

Tanzania Socio-Economic Database

Tanzania Socio-Economic Database Elide S Mwanri National Bureau of Statistics TANZANIA 1 Presentation • About TSED • How we can make use of Indicators • Examples of some MKUKUTA/MDGs indicators • Challenges and Next steps • Discussions 2 What is TSED? • It is an indicator and database administrator system that: – Facilitates systematization, storage and analysis of performance indicators – Contain tools for the generation of tables, graphs, reports and maps – Allows grouping of indicators in different frameworks – Currently has over 500 indicators from recognized sources • It has incrementally developed in the last few years with organizational, technical and financial support by the UN system and government • Institutionally set within the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) supported by 21 institutions, ministries and departments. Maintenance and updating is done at NBS • Linkages with the private sector and non government research institutions for training and capacity building. • Currently has over 500 indicators from recognized sources • TSED is currently running on stand-alone and on web (www.tsed.org). Tanzania one of the two countries piloting the web version. Based on DevInfo technology. 3 Why a common database? Data not easily accessible: - disperse in various institutions - restricted use within Ministries and Institutions - format not easy to access, read and process - no proper documentation (definitions/metadata) 4 Objectives Make data more accessible – managing the growing amount of information and enhancing availability and timely dissemination of socio-economic data in order to support policy analysis and decision making – Provide users with a comprehensive set of indicators that help Govt., donors and other interested people to analyze the situation in Tanzania Enhance statistical capacity and literacy – improve knowledge relevant to policy design /evaluation. -

Hergé and Tintin

Hergé and Tintin PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 20 Jan 2012 15:32:26 UTC Contents Articles Hergé 1 Hergé 1 The Adventures of Tintin 11 The Adventures of Tintin 11 Tintin in the Land of the Soviets 30 Tintin in the Congo 37 Tintin in America 44 Cigars of the Pharaoh 47 The Blue Lotus 53 The Broken Ear 58 The Black Island 63 King Ottokar's Sceptre 68 The Crab with the Golden Claws 73 The Shooting Star 76 The Secret of the Unicorn 80 Red Rackham's Treasure 85 The Seven Crystal Balls 90 Prisoners of the Sun 94 Land of Black Gold 97 Destination Moon 102 Explorers on the Moon 105 The Calculus Affair 110 The Red Sea Sharks 114 Tintin in Tibet 118 The Castafiore Emerald 124 Flight 714 126 Tintin and the Picaros 129 Tintin and Alph-Art 132 Publications of Tintin 137 Le Petit Vingtième 137 Le Soir 140 Tintin magazine 141 Casterman 146 Methuen Publishing 147 Tintin characters 150 List of characters 150 Captain Haddock 170 Professor Calculus 173 Thomson and Thompson 177 Rastapopoulos 180 Bianca Castafiore 182 Chang Chong-Chen 184 Nestor 187 Locations in Tintin 188 Settings in The Adventures of Tintin 188 Borduria 192 Bordurian 194 Marlinspike Hall 196 San Theodoros 198 Syldavia 202 Syldavian 207 Tintin in other media 212 Tintin books, films, and media 212 Tintin on postage stamps 216 Tintin coins 217 Books featuring Tintin 218 Tintin's Travel Diaries 218 Tintin television series 219 Hergé's Adventures of Tintin 219 The Adventures of Tintin 222 Tintin films -

The Ivory King "

NY PUBLIC LIBRARY THE BRANCH LIBRARIES 3 3333 08575 3305 u THE CENTRAL CHILDREN* S ROOM DON : CENTER 20 WES :et , NEW YORK, N.Y. 10019 THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY ASTOR, LF.NOX *"0 TILDt-N FoLKJD-.TIO.iS. C L. M 1|B| ». - A tiger's attack. By permission Illus. rated London News- Frontispiece. MARVELS OF ANIMAL LIFE SERIES. THE IVORY KING " A POPULAR HISTORY OF THE ELEPHANT AND ITS ALLIES BY CHARLES FREDERICK HOLDER ' FELLOW OF THE NEW YORK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, ETC. ; AUTHOR OF "ELEMENTS OF ZOOLOGY," " MARVELS OF ANIMAL LIFE," ETC. ILLUSTRATED: NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1902 TH-E NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY > . f>fiff A8TOB, LFNOX AWO THlOEN n-M i rtc» ! S. C ». Copyright, 1886, 1888, by CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS. Press op Berwick & Smith, Boston, U.S.A. C5^ X TO MY MOTHER STfjts Folume IS AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED- /> PREFACE. rTIHE elephant is the true king of beasts, the largest and most -*- powerful of existing land animals, and to young and old a never ceasing source of wonder and interest. In former geological ages, it roamed the continental areas of every zone ; was found in nearly every section of North America, from the shores of the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, and from New England to California. Where the hum of great cities is now heard, in by- gone days the trumpeting of the mastodon and elephant, and the cries of other strange animals, broke the stillness of the vast primeval forest. But they have all passed away, their extirpation undoubtedly hastened by the early man, the abori- ginal hunter ; and the mighty race of elephants, which now remains so isolated, is to-day represented by only two species, the African and the Asiatic, forms which are also doomed.