Book V Firebird

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geschichte Des Nationalsozialismus

Ernst Piper Ernst Ernst Piper Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus Von den Anfängen bis heute Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus Band 10264 Ernst Piper Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus Schriftenreihe Band 10291 Ernst Piper Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus Von den Anfängen bis heute Ernst Piper, 1952 in München geboren, lebt heute in Berlin. Er ist apl. Professor für Neuere Geschichte an der Universität Potsdam, Herausgeber mehrerer wissenschaft- licher Reihen und Autor zahlreicher Bücher zur Geschichte des 19. und 20. Jahrhun- derts. Zuletzt erschienen Nacht über Europa. Kulturgeschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs (2014), 1945 – Niederlage und Neubeginn (2015) und Rosa Luxemburg. Ein Leben (2018). Diese Veröffentlichung stellt keine Meinungsäußerung der Bundeszentrale fürpolitische Bildung dar. Für die inhaltlichen Aussagen trägt der Autor die Verantwortung. Wir danken allen Lizenzgebenden für die freundlich erteilte Abdruckgenehmigung. Die In- halte der im Text und im Anhang zitierten Internetlinks unterliegen der Verantwor- tung der jeweiligen Anbietenden; für eventuelle Schäden und Forderungen überneh- men die Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung / bpb sowie der Autor keine Haftung. Bonn 2018 © Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung Adenauerallee 86, 53113 Bonn Projektleitung: Hildegard Bremer, bpb Lektorat: Verena Artz Umschlagfoto: © ullstein bild – Fritz Eschen, Januar 1945: Hausfassade in Berlin-Wilmersdorf Umschlaggestaltung, Satzherstellung und Layout: Naumilkat – Agentur für Kommunikation und Design, Düsseldorf Druck: Druck und Verlagshaus Zarbock GmbH & Co. KG, Frankfurt / Main ISBN: 978-3-7425-0291-9 www.bpb.de Inhalt Einleitung 7 I Anfänge 18 II Kampf 72 III »Volksgemeinschaft« 136 IV Krieg 242 V Schuld 354 VI Erinnerung 422 Anmerkungen 450 Zeittafel 462 Abkürzungen 489 Empfehlungen zur weiteren Lektüre 491 Bildnachweis 495 5 Einleitung Dieses Buch ist eine Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus, keine deutsche Geschichte des 20. -

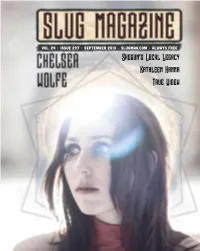

Shogun's Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow

Vol. 24 • Issue 297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com • Always Free Shogun’s Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow slugmag.com 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround slugmag.com 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 24 • Issue #297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com facebook.com/SLUG.Mag @SLUGMag @SLUGMag youtube.com/user/SLUGMagazine Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Manager: Editor: Angela H. Brown Karamea Puriri Managing Editor: Esther Meroño Marketing Team: Ischa B., Sabrina Costello, Editorial Assistant: Alexander Ortega Kristina Sandi, Brooklyn Ottens, Angella Luci- Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan sano, Nicole Roccanova, Raffi Shahinian, Vic- Digital Content Coordinator: Cody Kirkland toria Loveless, Zac Freeman, Cassie Anderson, Copy Editing Team: Esther Meroño, Alexan- Cassie Loveless, Shley Kinser, Matt Brunk, Robin der Ortega, Mary E. Duncan, Cody Kirkland, Sessions, Carl Acheson, Chandler Hunt Johnathan Ford, Alex Cragun, Rachel Miller, Ka- Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer tie Bald, Liz Phillips, Allison Shephard, Laikwan Waigwa-Stone, Shawn Soward Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Tony Cover Designer: Joshua Joye Bassett, Nancy Burkhart, Adam Okeefe, Ryan Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Worwood, John Ford, Matt Pothier, Phil Cannon, Design Team: Eleanor Scholz, BJ Viehl, Lenny Tim Kronenberg, Justin Nelson-Carruth, Xkot Riccardi, Chad Pinckney, Mason Rodrickc Toxsik, Nancy Perkins Ad Designers: Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Christian Broadbent, Kelli Tompkins, Eric Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, Mariah Sapp, Brad Barker, Paden Bischoff, Maggie Mann-Mellus, James Orme, Lance Saunders, Zukowski, Thy Doan, KJ Jackett, Nicholas Dowd, Bryer Wharton, Peter Fryer, James Bennett, Ricky Nick Ketterer Vigil, Gavin Hoffman, Esther Meroño, Rebecca Website Design: Kate Colgan Vernon, Jimmy Martin, Ben Trentelman, Princess Office Interns: Carl Acheson, Robin Sessions, Kennedy, Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Cody Hudson, Alex Cragun, Chandler Hunt Shawn Mayer, Dean O. -

Book V Firebird

Chapter XXIX - Aqualung 797 BOOK V FIREBIRD 798 Chapter XXIX - Aqualung Chapter XXIX - Aqualung 799 AQUALUNG The broad mass of a nation ... will more easily fall victim to a big lie than to a small one. Adolf Hitler "Mein Kampf", Vol. I, Ch. 10 One single will is necessary. Maximilien Robespierre, in a letter Captain Mayr was impressed with the talents of his new protégé Adolf Hitler, in particular with his ability to connect with soldiers, workers and simple men - something nationalist politicians had been unable to do in the Second Reich. After the defeat of Toller's, Levien's and Levine's Soviet Republics, the executive power which was nominally wielded by Hoffmann's SPD government in Bamberg, had been taken over by the army - Gruko 4 - on Mai 11, 1919, and it was soon made clear that no socialist activities were to be tolerated. KPD and USPD were strictly forbidden, as were even liberal newspapers. Gruko 4 understood its mission as counterrevolutionary, and Bavaria became a stronghold of the right: monarchists, reactionaries, nationalists, most of them anti-Semitic as well - the army protected them. The locals were reinforced by refugees from the east, mainly the Baltic States, who reported horror stories of Bolshevik atrocities. Alfred Rosenberg was born in Tallinn (Reval), Estonia, in 1893, and had studied engineering and architecture in Riga and Moscow. He fled the Bolshevik Revolution and emigrated first to Paris, then moved to Munich. (1) He was a fanatic pro- German, anti-Soviet, anti-Catholic and anti-Semitic theorist from a small-bourgeois background comparable to Hitler's. -

Der Kulturgeschichtspfad Als Druckversion

KulturGeschichtsPfad 6 Sendling Bereits erschienene und zukünftige Inhalt Publikationen zu den KulturGeschichtsPfaden: Stadtbezirk 01 Altstadt-Lehel Vorwort Oberbürgermeister Dieter Reiter 3 Stadtbezirk 02 Ludwigsvorstadt-Isarvorstadt Grußwort Bezirksausschussvorsitzender Stadtbezirk 03 Maxvorstadt Markus S. Lutz 5 Stadtbezirk 04 Schwabing-West Stadtbezirk 05 Au-Haidhausen Stadtbezirk 06 Sendling Geschichtliche Einführung 9 Stadtbezirk 07 Sendling-Westpark Stadtbezirk 08 Schwanthalerhöhe Rundgänge Stadtbezirk 09 Neuhausen-Nymphenburg Stadtbezirk 10 Moosach Stadtbezirk 11 Milbertshofen-Am Hart Rundgang 1: Sendlinger Oberfeld Stadtbezirk 12 Schwabing-Freimann Ortskern Untersendling 34 Stadtbezirk 13 Bogenhausen Am Harras 38 Stadtbezirk 14 Berg am Laim Postgebäude Am Harras 41 Stadtbezirk 15 Trudering-Riem Stadtbezirk 16 Ramersdorf-Perlach Verlag und Buchdruckerei B. Heller 43 Stadtbezirk 17 Obergiesing-Fasangarten Engelhardstraße 12 47 Stadtbezirk 18 Untergiesing-Harlaching Friedhof Sendling 50 Stadtbezirk 19 Thalkirchen-Obersendling- Albert Roßhaupter 51 Forstenried-Fürstenried-Solln Stadtbezirk 20 Hadern Sozialbürgerhaus Sendling-Westpark 53 Stadtbezirk 21 Pasing-Obermenzing Margaretenplatz 55 Stadtbezirk 22 Aubing-Lochhausen-Langwied Emma und Hans Hutzelmann 57 Stadtbezirk 23 Allach-Untermenzing Stemmerwiese 61 Stadtbezirk 24 Feldmoching-Hasenbergl Stadtbezirk 25 Laim Fritz Endres 63 Berlepschstraße 3 66 Optische und astronomische Werkstätte C. A. Steinheil Söhne 68 Zwei detaillierte Lagepläne zur Orientierung im Pedagogium Español 70 -

Atatürk Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi Atatürk University Journal of Faculty of Letters Sayı / Number 66, Haziran/ June 2021, 121-146

Atatürk Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi Atatürk University Journal of Faculty of Letters Sayı / Number 66, Haziran/ June 2021, 121-146 HİTLER DARBESİ (9 KASIM 1923) Hitler-Putsch (Nov 9 1923) (Makale Geliş Tarihi: 05.08.2020 / Kabul Tarihi: 25.01.2021) Oğuzhan EKİNCİ* Öz 1923 yılı, Weimar Cumhuriyeti için kriz yılı demekti. Fransa ve Bel- çika birlikleri, tazminat borçlarını ödeyemeyen Almanya’nın, ekonomisine en çok katkısı olan Ruhr bölgesini işgal etmişlerdi. Artan enflasyon ve işsizlikle uğraşan cumhuriyet, farklı eyalet hükümetlerinde yer alan aşırı sağ ve sol ce- nahlar tarafından tehdit edilmekteydi. Dahası mevcut yönetim, ordunun ba- şındaki General von Seeckt’in sadakatinden de emin değildi. Kendisini devle- tin düzen hücresi olarak gören ve cumhuriyetin kurulmasından sonra gittikçe sağa kayan Bavyera Eyaleti, olası bir darbe için ideal bir ortam sunmaktaydı. Adolf Hitler’in başını çektiği bir grup darbeci, Mussolini’nin Roma’ya yürü- yüşünü örnek alarak 9 Kasım 1923 tarihinde parlamenter demokrasiyi ortadan kaldırmak ve milliyetçi bir diktatörlük rejimi kurmak amacıyla bir darbe giri- şiminde bulundu. Bu çalışma, darbeyi hazırlayan ulusal ve yerel koşulları, dar- beye dâhil olan kişi ve grupları, bu başarısız darbe girişiminin akabindeki mahkeme sürecini, darbenin Hitler ve Almanya’nın siyasi hayatı açısından do- ğurduğu sonuçlarını Alman kaynaklarına dayanarak inceleyecektir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Weimar Cumhuriyeti, Bavyera, Nasyonal-Sosya- lizm, Hitler Darbesi. * Doç. Dr., Erzurum Teknik Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi, Sosyoloji Bölümü, Erzurum / TÜRKİYE. Assoc. Prof., Erzurum Technical University, Faculty of Literature, Department of Sociology, Erzurum / TURKEY. E-mail: [email protected], / ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1872- 2496 122 AÜEDFD 66 Oğuzhan EKİNCİ Abstract The year 1923 meant a crisis year for the Weimar Republic. -

Download Als PDF-Datei

Beiträge zum Parlamentarismus 19 Band 19 Wolfgang Reinicke Landtag und Regierung im Widerstreit. Der parlamentarische Neubeginn in Bayern 1946–1962 Herausgeber Bayerischer Landtag Maximilianeum Max-Planck-Straße 1 81675 München Postanschrift: Bayerischer Landtag 81627 München Telefon +49 89 4126-0 Fax +49 89 4126-1392 [email protected] www.bayern.landtag.de zum Parlamentarismus Beiträge Dr. Wolfgang Reinicke (geb. 1974 in Jena) ist wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte in Augsburg. Er hat an zahlreichen Ausstellungsprojekten mitgewirkt, leitet das Projekt Zeitzeugen und ist Mitglied im Projektteam für das neue Museum der Bayerischen Geschichte in Regensburg. München, November 2014 Bayerischer Landtag Landtagsamt Referat Öffentlichkeitsarbeit, Besucher Maximilianeum, 81627 München www.bayern.landtag.de ISBN-Nr. 978-3-927924-34-5 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet unter http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Landtag und Regierung im Widerstreit. Der parlamentarische Neubeginn in Bayern 1946–1962 Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät I der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Wolfgang Reinicke M.A. aus München 3 Erstgutachter: Professor Dr. Dirk Götschmann Zweitgutachter: Professor Dr. Dietmar Grypa Tag des Kolloquiums: 6. Februar 2013 4 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort 12 1 Einleitung -

Diagnosing Nazism: US Perceptions of National Socialism, 1920-1933

DIAGNOSING NAZISM: U.S. PERCEPTIONS OF NATIONAL SOCIALISM, 1920-1933 A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Robin L. Bowden August 2009 Dissertation written by Robin L. Bowden B.A., Kent State University, 1996 M.A., Kent State University, 1998 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Mary Ann Heiss , Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Clarence E. Wunderlin, Jr. , Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Kenneth R. Calkins , Steven W. Hook , James A. Tyner , Accepted by Kenneth J. Bindas , Chair, Department of History John R. D. Stalvey , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………..………………………………………………iv Chapter 1. Introduction: U.S. Officials Underestimate Hitler and the Nazis……..1 2. Routine Monitoring: U.S. Officials Discover the Nazis…………......10 3. Early Dismissal: U.S. Officials Reject the Possibility of a Recovery for the Nazis…………………………………………….....57 4. Diluted Coverage: U.S. Officials Neglect the Nazis………………..106 5. Lingering Confusion: U.S. Officials Struggle to Reassess the Nazis…………………………………………………………….151 6. Forced Reevaluation: Nazi Success Leads U.S. Officials to Reconsider the Party……………………………………………......198 7. Taken by Surprise: U.S. Officials Unprepared for the Success of the Nazis……………………...……………………………….…256 8. Conclusion: Evaluating U.S. Reporting on the Nazis…………..…..309 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………318 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation represents the culmination of years of work, during which the support of many has been necessary. In particular, I would like to thank two graduate school friends who stood with me every step of the way even as they finished and moved on to academic positions. -

Maria Christina Müller

Maria Christina Müller Der Wehrverband als Bürgerpflicht? Mobilisierung und Militarisierung in der bayerischen Wirtschaftselite nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg Augsburger historische Studien | Band 2 Augsburger historische Studien Band 2 Editorial In der Reihe Augsburger historische Studien werden herausragende Abschluss- arbeiten der historischen Lehrstühle an der Universität Augsburg veröffentlicht. Die zeitliche Spanne der Publikationen reicht von der Alten über die Mittelalter- liche und die Geschichte der Frühen Neuzeit bis zur Neueren und Neuesten Geschichte. Lokal- und regionalgeschichtliche Untersuchungen zur Bayerischen und Schwäbischen Landesgeschichte sind ebenso vertreten wie Arbeiten mit nationalen und transnationalen Leitfragen. Die Reihe führt kulturhistorische, politikgeschichtliche und sozialhistorische Ansätze zusammen und ist offen für unterschiedliche methodische Zugänge wie Oral History, Visual History, Mikro- historie oder Diskursanalyse. Die Reihe Augsburger historische Studien versteht sich als lebendiges Forum, das es dem hoch qualifizierten wissenschaftlichen Nachwuchs ermöglicht, seine Forschungen der Öffentlichkeit vorzustellen. Maria Christina Müller Der Wehrverband als Bürgerpflicht? Mobilisierung und Militarisierung in der bayerischen Wirtschaftselite nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg Bibliographische Informationen Müller, Maria Christina: Der Wehrverband als Bürgerpflicht? Mobilisierung und Militarisierung in der bayerischen Wirtschaftselite nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg [online], Augsburg Uni. 2015. ISBN: 978-3-945544-01-3 -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Royal Wood – Ghost Light • Rufus Wainwright

Royal Wood – Ghost Light Rufus Wainwright – Take All My Loves: 9 Shakespeare Sonnets André Rieu – Magic Of The Waltz Check out new releases in our Vinyl Section! New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI16-15 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 *Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Various Artists / Now! 26 Bar Code: Cat. #: 0254782454 Price Code: G Order Due: March 3, 2016 Release Date: April 1, 2016 6 02547 82454 7 File: Pop Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: 25 Key Tracks: SUPER SHORT SELL Key Points: National Major TV, Radio Online Advertising Campaign Now! Brand is consistently one of the strongest and best‐selling compilations every year The NOW! brand has generated sales of over 200 million albums worldwide Sold over 4 million copies in Canada since its debut. Includes: Justin Bieber – Sorry Selena Gomez ‐ Same Old Love Coleman Hell ‐ 2 Heads Shawn Mendes ‐ Stitches Ellie Goulding ‐ On My Mind Alessia Cara ‐ Here DNCE ‐ Cake By The Ocean Demi Lovato ‐ Confident Nathaniel Rateliff & The Night Sweats ‐ S.O.B Hedley ‐ Hello James Bay ‐ Let It Go Mike Posner ‐ I Took A Pill In Ibiza And more….. Also Available: Artist/Title: Various / Now! 25 Cat#: 0254750866 Price Code: JSP UPC#: 02547 50866 6 9 INTERNAL USE Label Name: Universal Music Canada Territory: Domestic Release Type: O For additional artist information please contact Nick at 416‐718‐4045 or [email protected] UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Avenue, Suite 1, Toronto, ON M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718‐4000 Fax: (416) 718‐4218 UNIVERS AL M USI C CA NAD A N EW RELEASE Artist/Title: THE STRUMBELLAS / HOPE (CD) Cat. -

Download Complete File

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Volume XXXIII, No. 2 November 2011 CONTENTS Article The Power of Weakness: Machiavelli Revisited (Annette Kehnel) 3 Book Reviews James T. Palmer, Anglo-Saxons in a Frankish World, 690–900 (Dominik Waßenhoven) 35 Jens Schneider, Auf der Suche nach dem verlorenen Reich: Loth arin gien im 9. und 10. Jahrhundert (Levi Roach) 39 Giles Constable, Crusaders and Crusading in the Twelfth Century (Dorothea Weltecke) 46 Folker Reichert with the assistance of Margit Stolberg- Vowinckel (eds.), Quellen zur Geschichte des Reisens im Spätmittel alter (Alan V. Murray) 50 Howard Louthan, Converting Bohemia: Force and Persuasion in the Catholic Reformation; Rita Krueger, Czech, German and Noble: Status and National Identity in Habsburg Bohemia (Joachim Bahlcke) 53 Gisela Mettele, Weltbürgertum oder Gottesreich: Die Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine als globale Gemeinschaft 1727–1857 (Katherine Carté Engel) 58 Derek Beales, Joseph II, ii. Against the World, 1780–1790 (Reinhard A. Stauber) 62 (cont.) Contents Colin Storer, Britain and the Weimar Republic: The History of a Cultural Relationship (Thomas Wittek) 66 Derek Hastings, Catholicism and the Roots of Nazism: Religious Identity and National Socialism (Christoph Kösters) 71 Eckart Conze, Norbert Frei, Peter Hayes, and Moshe Zim mer- mann, Das Amt und die Vergangenheit: Deutsche Diplomaten im Dritten Reich und in der Bundesrepublik (Eckard Michels) 76 Stefan Berger and Norman LaPorte, Friendly Enemies: Britain and the GDR, 1949–1990 (Arnd Bauerkämper) 83 Conference Reports Networking across the Channel: England and Halle Pietism in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Erik Nagel) 87 From Planning to Crisis Management? Time, Futures, and Politics in West Germany and Britain from the 1960s to the 1980s (Reinhild Kreis) 94 Global History: Connected Histories or a History of Connec- tions? (Birgit Tremml) 98 Middle East Missions: Nationalism, Religious Liberty, and Cultural Encounter (Heather J. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produiæd from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original subm itted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "targ e t" for pages apparently lackingfrom the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you com plete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image o f the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections w ith a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until com plete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Música Sin Flash

SUMARIO ROCKAXIS 181 MAYO 2018 26 Camila Moreno Las raíces de Pangea, su proyecto más ambicioso 16 20 34 40 46 Facebook Jack White Erasure Han Solo Arctic Monkeys Bienvenidos a la “No voy a dejar que Un aliento de vida Por qué se merece Club de caballeros máquina nada me encierre”, su propio spin admite el músico off? Expertos responden Identidad Editorial Dirección general: Alfredo Lewin sta editorial es muy espe- Cote Hurtado cial y la escribo inspirado por la mujer que luce la Editora: María de los Ángeles Cerda portada de esta Rockaxis #181. Me la permito Comité editorial: Cote Hurtado porque la sensación de María de los Angeles Cerda “¡Basta ya!” es demasia- Francisco Reinoso do notoria y las condiciones dadas hoy son Marcelo Contreras Eextraordinarias. Hace algo así como un año Nuno Veloso y a partir del debate generado por el maltrato César Tudela de Tea Time (Los Tetas) a su pareja, Camila Moreno quiso aportar con lo suyo y a través Alejandro Bonilla (Colombia) de una publicación en su página de Facebook dio a conocer distintos episodios de violencia Staff: Héctor Aravena y abuso que a ella le tocó vivir en estos últi- Andrés Panes mos 15 años. Jean Parraguez Sufrir de violencia machista remece, lejos de Rodrigo Bravo ser un hecho aislado, representa la situación que enfrentan mujeres, en ocasiones anó- Cristián Pavez nimamente y por cierto, pasa todos los días. La diferencia es que hoy está empezando a haber una suerte de registro del abuso, todo a través de un movimiento que en un Colaboradores: Pablo Padilla momento pareció levantar la voz y hacernos ver que es increíble que estas cosas sigan Felipe Kraljevich pasando.