Book V Firebird

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Ed 2 June 2015 2 June Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Western Front The Western Creative Media Design ADR003970 Edition 2 June 2015 The Somme Battlefield: Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The Somme Battlefield: Lochnagar Crater. It was blown at 0728 hours on 1 July 1916. Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front 2nd Edition June 2015 ii | THE WESTERN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR ISBN: 978-1-874346-45-6 First published in August 2014 by Creative Media Design, Army Headquarters, Andover. Printed by Earle & Ludlow through Williams Lea Ltd, Norwich. Revised and expanded second edition published in June 2015. Text Copyright © Mungo Melvin, Editor, and the Authors listed in the List of Contributors, 2014 & 2015. Sketch Maps Crown Copyright © UK MOD, 2014 & 2015. Images Copyright © Imperial War Museum (IWM), National Army Museum (NAM), Mike St. Maur Sheil/Fields of Battle 14-18, Barbara Taylor and others so captioned. No part of this publication, except for short quotations, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Editor and SO1 Commemoration, Army Headquarters, IDL 26, Blenheim Building, Marlborough Lines, Andover, Hampshire, SP11 8HJ. The First World War sketch maps have been produced by the Defence Geographic Centre (DGC), Joint Force Intelligence Group (JFIG), Ministry of Defence, Elmwood Avenue, Feltham, Middlesex, TW13 7AH. United Kingdom. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87577-6 - The Cambridge History of War: War and the Modern World: Volume IV Edited by Roger Chickering, Dennis Showalter and Hans van de Ven Index More information Index A. Q. Khan network 485 importance of power in 569, 579 Acheson, Dean 498, 554, 557 and Spanish Civil War 330 Adan, Avraham 507, 508 see also Afghanistan; Iraq; RMA; Royal Air Aden, insurgency in 539 Force British withdrawal from 539 Akiyoshi Yamada, General 106 and Marxist People’s Republic with Al Qaeda, September 11 terror attacks 582 Yemen 539 see also Afghanistan Adenauer, Konrad 545 Algeria, French colonial rule in 526 Afghanistan military aspects of 529–30 insurgency in 586 Algerian War and US army reform 587 ALN attacks, and French response 527 Operation Anaconda 583–84 casualty numbers in 539–40 lack of collaboration between US and de Gaulle’soffensive 528 allies 584 formation of OAS 529 terrorist sanctuary 582 and FLN 526–27 US support for Northern Alliance 582–83 criticism of France 528 US airstrikes 583 French attempts to remove activists 528 Africa negotiations with 528 civil wars in and use of military and victory 529 technology 581 and idea of postwar European peace division of former German colonies 560–61 287–88 use of French conscripts 527 military organization of colonies in 138–39 Ali, Mehmet 11 age of mass 165 Alsace-Lorraine, and France’s Plan XV 62 agricultural crises, and war 9 Amazons of Dahomey 91 agricultural economies, challenges to 268 Ambrosio, General Vittorio 364 agriculture, advances in, and American Civil -

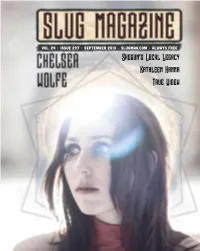

Shogun's Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow

Vol. 24 • Issue 297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com • Always Free Shogun’s Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow slugmag.com 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround slugmag.com 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 24 • Issue #297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com facebook.com/SLUG.Mag @SLUGMag @SLUGMag youtube.com/user/SLUGMagazine Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Manager: Editor: Angela H. Brown Karamea Puriri Managing Editor: Esther Meroño Marketing Team: Ischa B., Sabrina Costello, Editorial Assistant: Alexander Ortega Kristina Sandi, Brooklyn Ottens, Angella Luci- Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan sano, Nicole Roccanova, Raffi Shahinian, Vic- Digital Content Coordinator: Cody Kirkland toria Loveless, Zac Freeman, Cassie Anderson, Copy Editing Team: Esther Meroño, Alexan- Cassie Loveless, Shley Kinser, Matt Brunk, Robin der Ortega, Mary E. Duncan, Cody Kirkland, Sessions, Carl Acheson, Chandler Hunt Johnathan Ford, Alex Cragun, Rachel Miller, Ka- Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer tie Bald, Liz Phillips, Allison Shephard, Laikwan Waigwa-Stone, Shawn Soward Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Tony Cover Designer: Joshua Joye Bassett, Nancy Burkhart, Adam Okeefe, Ryan Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Worwood, John Ford, Matt Pothier, Phil Cannon, Design Team: Eleanor Scholz, BJ Viehl, Lenny Tim Kronenberg, Justin Nelson-Carruth, Xkot Riccardi, Chad Pinckney, Mason Rodrickc Toxsik, Nancy Perkins Ad Designers: Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Christian Broadbent, Kelli Tompkins, Eric Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, Mariah Sapp, Brad Barker, Paden Bischoff, Maggie Mann-Mellus, James Orme, Lance Saunders, Zukowski, Thy Doan, KJ Jackett, Nicholas Dowd, Bryer Wharton, Peter Fryer, James Bennett, Ricky Nick Ketterer Vigil, Gavin Hoffman, Esther Meroño, Rebecca Website Design: Kate Colgan Vernon, Jimmy Martin, Ben Trentelman, Princess Office Interns: Carl Acheson, Robin Sessions, Kennedy, Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Cody Hudson, Alex Cragun, Chandler Hunt Shawn Mayer, Dean O. -

The Battle of the Ardennes 22 August 1914

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Battle of the Ardennes 22 August 1914 House, Simon Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 This electronic theses or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Battle of the Ardennes 22 August 1914 Title: Author: Simon House The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. -

The Schlieffen Plan

The Schlieffen Plan Was the German General Staff's early 20th century overall strategic plan for victory in a possible future war where it might find itself fighting on two fronts: France to the west and Russia to the east. The First World War later became such a war with both a Western Front and an Eastern Front. The plan took advantage of expected differences in the three countries' speed in preparing for war. In short, it was the German plan to avoid a two-front war by concentrating their troops in the west, quickly defeating the French and then, if necessary, rushing those troops by rail to the east to face the Russians before they had time to mobilize fully. The Schlieffen Plan was created by Count Alfred von Schlieffen and modified by Helmuth von Moltke the Younger after Schlieffen's retirement. It was Moltke who actually put the plan into action, despite initial reservations about it. In modified form, it was executed to near victory in the first month of World War I; however, the modifications to the original plan, a French counterattack on the outskirts of Paris (the Battle of the Marne), and surprisingly speedy Russian offensives, ended the German offensive and resulted in years of trench warfare. The plan has been the subject of intense debate among historians and military scholars ever since. Schlieffen's last words were "remember to keep the right flank strong", a request which was watered down by Moltke. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schlieffen_Plan The Battle of Marne The Battle of the Marne was a First World War battle fought between 5 and 12 September 1914. -

The Battle of the Marne in Memoriam N

THE BATTLE OF THE MARNE IN MEMORIAM N. F. P. + E. L. P. fhetmnfi Douat# POSITIONS firms'* Bonchx t& ARMIES Doultzris Camb onifk'&xtf die. Battle*- mndt&c «<rvtml vtrtMtiv GB*man Armies. I-Von Kliick. H-Von Biilow. HI-Von Hansen. IV-Duke of Wurtemberg. V~ Imperial Crown Prince. VPC. Princa of Bavaria. (& troops from Metz) VTT Vbn Heeringen French & BritL-sh Annies: 6-Maimoupy-.. B.E.E British. 5-F.d'Espcrey-.. 9-Foch 4-DeLanole deCary. 3-SarraiL 2-DeCa5*elnau.. f-DubaiL... vr eLcLpgae-rmms Plia.lsboLWgr '8 0 Save l]Jt::£lainon ,MI DONON _ ST!/ ? — SchMtskadt*tstao 51.Marie 'jVisLri^A'ay --.uns'ter V. THE BATTLE OF THE MARNE BY GEORGE HERBERT PERRIS SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT OF "THE DAILY CHRONICLE" WITH THE FRENCH ARMIES, 1914-18 WITH TWELVE MAPS JOHN W. LUCE & CO. BOSTON MCMXX PREFACE HE great war has entered into history. The restraints, direct and indirect, which it imposed being gone with it, we return to sounder tests of what should be public knowledge—uncomfortable truths may be told, secret places explored. At the same time, the first squall of controversy in France over the opening of the land campaign in the West has subsided; this lull is the student's opportunity. No complete history of the events culminating in the victory of the Marne is yet possible, or soon to be expected. On the German side, evidence is scanty and of low value ; on that of the Allies, there is yet a preliminary work of sifting and measuring to undertake ere definitive judgments can be set down. -

L'écho Des Tranchées

L’Écho des Tranchées Quarter 4 - 2020 Nr 66 - Page : 1 ASSOCIATION LOOS, SUR LES TRACES DE LA GRANDE GUERRE L’Écho des tranchées From our President We end the year 2020 with a sad news: the disappearance of our friend Peter Dans ce numéro : Last who was a man passionate about the history of the First World War and especially of the Battle of Loos. On behalf - From our President, 1 - Biography of Emilienne of the members of our association, I offer my sincere condo- Moreau, 2 lences to his family. - From the Navy to the Infantry ….. an Unusual It has been possible for our Association to arrange only Journey, 3 - Private Alexandre Renaud ’ s a very few activities in the final period of 2020 because of War,4 the health crisis. The Musée Alexandre Villedieu remains closed, with all visits being cancelled long with all of our projects for the time being. The Rotary Club at Weppes La Bassée invited us to present a setting of the Battle of Loos by way of a diorama at their base in Douvrin. Elsewhere, Notre Dame de Lorette hosted a visit by Jean Claude Skrela, the former French interna- tional rugby player and coach who led his team to the 1999 World Cup Final and won the Grand Slam with them: he was in the Hauts - de - France region to see for himself places commemorating the Great War. His guide for the occasion was Mi- chel Merckel, the author of “ 14 - 18: Le Sport Sort des Tranchées ”, while Monsieur Dreux, President of the Anciens Combattants (Veterans) Association, and his stan- dard bearer were invited to the gathering which paid tribute to international rugby players who fell on the field of honour. -

1914, Offensive À Outrance the Initial Campaigns on the Western Front in WWI

1914, Offensive à outrance The Initial Campaigns on the Western Front in WWI PLAYBOOK 2015-April 27 TABLE OF CONTENTS 28.0 Set-Up Explanation 29.0 Battle for Lorraine 30.0 1914, The Grand Campaign 31.0 The Race to the Sea 32.0 The Last Battles of 1914 Fortress Unit Setup List Extra Unit Counter List Unit ID Abbreviations Designer’s Notes 1 28.0 SET-UP EXPLANATION boundary can be placed anywhere between the units assigned to 28.1 Organizing the Units adjacent armies. Use the counter-sheet “spines” labeled ‘Army Area of To prepare to set-up, both players should sort their units into the Attachment Boundary’ for marking these boundaries. following subgroups, as per the set-up grids: C. Army Markers: Place each army’s double-sized Army marker • Fortress units; anywhere just behind that army’s Area of Attachment. Place the marker • Fort units; on either its front or back-side (as appropriate) to record whether the • Army units; army is still on its Strategic Plan or not as designated in the set-up for • Units attached to a Corps; the selected scenario. The exact location of these markers is not • Independent Infantry Formations; relevant—they are just reminders to players as to which army is which, • LOC formations; and whether each army is still on its Strategic Plan or not. D. Railhead Markers: Place each player’s Railhead markers on as • Infantry Asset units; listed under the scenario rules. • Cavalry units; E. RPs and REPLs Markers: Place each nation’s Rail Points and • Artillery and Siege units; Replacements markers on their respective Resources displays. -

The Battle of the Marne in M E M O R I a M

9'^ f<^ CDCO O CO •CD CO ;0 .CD .1^ Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 THE BATTLE OF THE MARNE IN M E M O R I A M N. F. P. + E. L. P. Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/battleofmarnOOperr . ttr^ (qfcneral IVlap shcwma VOSlTlOKoP ta ARMIES on the Pvc cftne Bztdc: suxdtEc cctttfeii(}cvmazv lines ofApproick Germem Arraias I-VonKLuck. II-VonBiilow. ni-Von Hansen . IV-Duke of Wiirtjerabepg. V- I-mperbsd. Crown Prmcc. VI-C. Prnrbcxz of Bavaria (c^- /rocps )9'OT7i Metz) VH- "Vbn He<2rmg<zn French & British Arrnias ; 6-Maiincnipy.. B.E-K Brliish 5-E d'Espcrey . 9- Foch. 4-DeLanal2deCary. 3-SarraiL 1- S-DeCasteLnaoi . DubadL . ntzPtzviUe f "l/IT MI DONON ^ ®-^/^Sw '""*' °^* Schjittstadt .^ S't'.Mar'ie Bpixyeres i ;•• -^ • ^-. , # /^i^'»lma.T* * *^^ \ /Sir * * iV ^^ Qaunster «S^ V^ Miles u^"''^ >.?<jSlV£j4r IHE BATTUEwim^^ THE MARN£;.,J^ BY GEORGE HERBERT PERRIS SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT OF "THE DAILY CHRONICLE" WITH THE FRENCH ARMIES, 1914-18 WITH TWELVE IVTAPS METHUEN & GO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET W.G. LONDON %r. First Published in IQ20 PREFACE THE great war has entered into history. The restraints, diiect and indirect, which it imposed being gone with it, we return to sounder tests of what should be pubUc knowledge—uncomfortable truths may be told, secret places explored. At the same time, the first squall of controversy in France over the opening of the land campaign in the West has subsided ; this lull is the student's opportunity. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Royal Wood – Ghost Light • Rufus Wainwright

Royal Wood – Ghost Light Rufus Wainwright – Take All My Loves: 9 Shakespeare Sonnets André Rieu – Magic Of The Waltz Check out new releases in our Vinyl Section! New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI16-15 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 *Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Various Artists / Now! 26 Bar Code: Cat. #: 0254782454 Price Code: G Order Due: March 3, 2016 Release Date: April 1, 2016 6 02547 82454 7 File: Pop Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: 25 Key Tracks: SUPER SHORT SELL Key Points: National Major TV, Radio Online Advertising Campaign Now! Brand is consistently one of the strongest and best‐selling compilations every year The NOW! brand has generated sales of over 200 million albums worldwide Sold over 4 million copies in Canada since its debut. Includes: Justin Bieber – Sorry Selena Gomez ‐ Same Old Love Coleman Hell ‐ 2 Heads Shawn Mendes ‐ Stitches Ellie Goulding ‐ On My Mind Alessia Cara ‐ Here DNCE ‐ Cake By The Ocean Demi Lovato ‐ Confident Nathaniel Rateliff & The Night Sweats ‐ S.O.B Hedley ‐ Hello James Bay ‐ Let It Go Mike Posner ‐ I Took A Pill In Ibiza And more….. Also Available: Artist/Title: Various / Now! 25 Cat#: 0254750866 Price Code: JSP UPC#: 02547 50866 6 9 INTERNAL USE Label Name: Universal Music Canada Territory: Domestic Release Type: O For additional artist information please contact Nick at 416‐718‐4045 or [email protected] UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Avenue, Suite 1, Toronto, ON M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718‐4000 Fax: (416) 718‐4218 UNIVERS AL M USI C CA NAD A N EW RELEASE Artist/Title: THE STRUMBELLAS / HOPE (CD) Cat. -

Book IV EKPYROSIS

Chapter XVIII – De Bello Gallico 479 Book IV EKPYROSIS 480 Chapter XVIII – De Bello Gallico Chapter XVIII - De Bello Gallico 481 DE BELLO GALLICO War is the orgasm of universal life which fructifies and moves chaos, the prelude for all creations, and which like Christ the Saviour triumphs beyond death through death itself. P.J. Proudhon, French theorizer (1846) If there is ever another war in Europe, it will come out of some damned silly thing in the Balkans. Otto von Bismarck, German practitioner, probably apocryphal (1877) Beyond the mistakes of individuals, the outbreak of the Great War may be seen as a result of the self-aggravating interplay of three processes: the ruin of the balance of powers, i.e., the replacement of the concert-of-powers by two antagonistic alliance systems, the rise of liberalism and nationalism, and rapid industrialization, which, for purposes of war, made available railways, telegraphs, and improved gun technology. The improvement of agriculture also allowed to feed more conscripts. We recall that the last two major reorganizations of the continent's political order had occurred at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which, ending the Thirty-Years War together with most of the former imperial prerogatives, augured in the eventual collapse of the Holy Roman Empire, and within the structure formalized at the Congress of Vienna, which administered the receivership of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Both designs accelerated the demise of feudalism, even if monarchical decorum was often maintained, and the rise of the bourgeoisie; the replacement of the divine authority of the kings with the cooperative structures of the modern nation-state. -

Book V Firebird

Chapter XXIX - Aqualung 797 BOOK V FIREBIRD 798 Chapter XXIX - Aqualung Chapter XXIX - Aqualung 799 AQUALUNG The broad mass of a nation ... will more easily fall victim to a big lie than to a small one. Adolf Hitler "Mein Kampf", Vol. I, Ch. 10 One single will is necessary. Maximilien Robespierre, in a letter Captain Mayr was impressed with the talents of his new protégé Adolf Hitler, in particular with his ability to connect with soldiers, workers and simple men, something no nationalist politician had been able to do in the Second Reich. After the defeat of Toller's, Levien's and Levine's Soviet Republics, the executive power which was nominally wielded by Hoffmann's SPD government in Bamberg, had been taken over by the army - Gruko 4 - on Mai 11, 1919, and it was soon made clear that no socialist activities were to be tolerated. KPD and USPD were strictly forbidden, as were even liberal newspapers. Gruko 4 understood its mission as counterrevolutionary, and Bavaria became a stronghold of the right: monarchists, reactionaries, nationalists, most of them anti-Semitic as well; the army protected them all. The Bavarian element was reinforced by refugees from the east, mainly the Baltic States, who reported horror stories of Bolshevik atrocities. Alfred Rosenberg was born in Tallinn (Reval), Estonia, in 1893, and had studied engineering and architecture in Riga and Moscow. He fled the Bolshevik Revolution and emigrated first to Paris, then to Munich. (1) He was a fanatic pro- German, anti-Soviet, anti-Catholic and anti-Semitic theorist from a small-bourgeois background comparable to Hitler's.