The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War I Casualty Biographies

St Martins-Milford World War I Casualty Biographies This memorial plaque to WW1 is in St Martin’s Church, Milford. There over a 100 listed names due to the fact that St Martin’s church had one of the largest congregations at that time. The names have been listed as they are on the memorial but some of the dates on the memorial are not correct. Sapper Edward John Ezard B Coy, Signal Corps, Royal Engineers- Son of Mr. and Mrs. J Ezard of Manchester- Husband of Priscilla Ezard, 32, Newton Cottages, The Friary, Salisbury- Father of 1 and 5 year old- Born in Lancashire in 1883- Died in hospital 24th August 1914 after being crushed by a lorry. Buried in Bavay Communal Cemetery, France (12 graves) South Part. Private George Hawkins 1st Battalion Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry- Son of George and Caroline Hawkins, 21 Trinity Street, Salisbury- Born in 1887 in Shrewton- He was part of the famous Mon’s retreat- His body was never found- Died on 21st October 1914. (818 died on that day). Commemorated on Le Touret Memorial, France. Panel 19. Private Reginald William Liversidge 1st Dorsetshire Regiment- Son of George and Ellen Liversidge of 55, Culver Street, Salisbury- Born in 1892 in Salisbury- He was killed during the La Bassee/Armentieres battles- His body was never found- Died on 22nd October 1914 Commemorated on Le Touret Memorial, France. Panel 22. Corporal Thomas James Gascoigne Shoeing Smith, 70th Battery Royal Field Artillery- Husband of Edith Ellen Gascoigne, 54 Barnard Street, Salisbury- Born in Croydon in 1887-Died on wounds on 30th September 1914. -

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

The First World War Centenary Sale | Knightsbridge, London | Wednesday 1 October 2014 21999

ALE S ENARY ENARY T WORLD WAR CEN WORLD WAR T Wednesday 1 October 2014 Wednesday Knightsbridge, London THE FIRS THE FIRST WORLD WAR CENTENARY SALE | Knightsbridge, London | Wednesday 1 October 2014 21999 THE FIRST WORLD WAR CENTENARY SALE Wednesday 1 October 2014 at 1pm Knightsbridge, London BONHAMS ENQUIRIES SALE NUMBER IMPORTANT INFORMATION Montpelier Street 21999 The United States Government Knightsbridge Books, Manuscripts, has banned the import of ivory London SW7 1HH Photographs and Ephemera CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing www.bonhams.com Matthew Haley £20 ivory are indicated by the symbol +44 (0)20 7393 3817 Ф printed beside the lot number VIEWING [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder in this catalogue. Sunday 28 September information including after-sale 11am to 3pm Medals collection and shipment. Monday 29 September John Millensted 9am to 4.30pm +44 (0)20 7393 3914 Please see back of catalogue Tuesday 30 September [email protected] for important notice to bidders 9am to 4.30pm Wednesday 1 October Militaria ILLUSTRATIONS 9am to 11am David Williams Front cover: Lot 105 +44 (0)20 7393 3807 Inside front cover: Lot 48 BIDS [email protected] Inside back cover: Lot 128 +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Back cover: Lot 89 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Pictures and Prints To bid via the internet Thomas Podd please visit www.bonhams.com +44 (0)20 7393 3988 [email protected] New bidders must also provide proof of identity when submitting Collectors bids. Failure to do this may result Lionel Willis in your bids not being processed. -

General Sir William Birdwood and the AIF,L914-1918

A study in the limitations of command: General Sir William Birdwood and the A.I.F.,l914-1918 Prepared and submitted by JOHN DERMOT MILLAR for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales 31 January 1993 I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of advanced learning, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. John Dermot Millar 31 January 1993 ABSTRACT Military command is the single most important factor in the conduct of warfare. To understand war and military success and failure, historians need to explore command structures and the relationships between commanders. In World War I, a new level of higher command had emerged: the corps commander. Between 1914 and 1918, the role of corps commanders and the demands placed upon them constantly changed as experience brought illumination and insight. Yet the men who occupied these positions were sometimes unable to cope with the changing circumstances and the many significant limitations which were imposed upon them. Of the World War I corps commanders, William Bird wood was one of the longest serving. From the time of his appointment in December 1914 until May 1918, Bird wood acquired an experience of corps command which was perhaps more diverse than his contemporaries during this time. -

The Battle of Cambrai

THE BATTLE OF CAMBRAI GERMAN OCCUPATION REPORTS / MAPS / PICTURES THE BATTLE OF CAMBRAI Although its noise and fury could be heard from the town itself, in reality the Battle of Cambrai took place across the south of the Cambrésis. The confrontations which happened between November 20 th and December 7 th , 1917, setting They are assuring us that the 476 British armoured vehicles against the German Army, town of Cambrai was on the point protected by the Hindenburg line, were imprinted on the spirits of those who lived there, and destroyed whole villages. of being liberated yesterday, that the English got as far as Noyelles , Today the apocalyptic landscape created by the battle has that the Germans were going to given way to cultivated fields and rebuilt villages, but the deeply moving memories remain: photographs, personal flee without worrying about the diaries, blockhouses, cemeteries... population, but that the attack The ‘Cambrai : Town of Art and History’ service and the stopped suddenly and that our Cambresis Tourist Office invite you to discover this land, allies withdrew by two miles this so physically marked by the terrible conflicts of the last morning. Powerful reinforcements Fortified position - Hindenburg line century, many remnants of which are housed at the Cambrai German defensive line Tank 1917 museum. were sent to the Germans and ENGLISH POSITIONS we are still held in the chains of Cambresis Tourist Office British position on november 20 th 1917 48 rue de Noyon - 59400 Cambrai our slavery. Place du Général de Gaulle - 59540 Caudry Mrs Mallez, 21 November 1917 Place du Général de Gaulle - 59360 Le Cateau-Cambrésis British farthest position during 03 27 78 36 15 • [email protected] the Battle of Cambrai www.tourisme-cambresis.fr Only a few large, isolated shells fell now, one of which exploded immediately in front th of us, a welcome from hell, filling all the British position on december 7 1917 canal bed in a heavy and sombre smoke. -

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 11, 1916

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 11, 1916 Table of Contents OFFICERS AND COMMITTEES .......................................................................................5 PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-SEVENTH TO THIRTY-NINTH MEETINGS .............................................................................................7 PAPERS EXTRACTS FROM LETTERS OF THE REVEREND JOSEPH WILLARD, PRESIDENT OF HARVARD COLLEGE, AND OF SOME OF HIS CHILDREN, 1794-1830 . ..........................................................11 By his Grand-daughter, SUSANNA WILLARD EXCERPTS FROM THE DIARY OF TIMOTHY FULLER, JR., AN UNDERGRADUATE IN HARVARD COLLEGE, 1798- 1801 ..............................................................................................................33 By his Grand-daughter, EDITH DAVENPORT FULLER BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF MRS. RICHARD HENRY DANA ....................................................................................................................53 By MRS. MARY ISABELLA GOZZALDI EARLY CAMBRIDGE DIARIES…....................................................................................57 By MRS. HARRIETTE M. FORBES ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TREASURER ........................................................................84 NECROLOGY ..............................................................................................................86 MEMBERSHIP .............................................................................................................89 OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY -

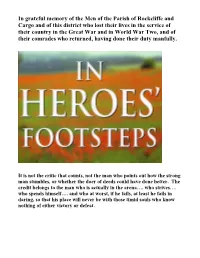

In Grateful Memory of the Men of the Parish of Rockcliffe and Cargo And

In grateful memory of the Men of the Parish of Rockcliffe and Cargo and of this district who lost their lives in the service of their country in the Great War and in World War Two, and of their comrades who returned, having done their duty manfully. It is not the critic that counts, not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or whether the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena…. who strives…. who spends himself…. and who at worst, if he fails, at least he fails in daring, so that his place will never be with those timid souls who know nothing of either victory or defeat. At the going down of the sun, And in the morning We will remember them. A cross of sacrifice stands in all Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries on the Western Front. The War Memorial of the Parish of Rockcliffe and Cargo. It is 2010. In far off Afghanistan young men and women of various nations are putting their lives at risk as they struggle to defeat a tenacious enemy. We receive daily reports of the violent death of some while still in their teens. Others, of whom we hear little, are horribly maimed for life. We here, in the relative safety of the countries we call The British Isles, are free to discuss from our armchair or pub stool the rights and wrongs of such a conflict. That right of free speech, whatever our opinion or conclusion, was won for us by others, others who are not unlike today’s almost daily casualties of a distant war. -

THE BATTLE of FRANCE (July 19 to August 29, 1944)

THE BATTLE OF FRANCE (July 19 to August 29, 1944) N our last issue's review of the invasion battle 31. This breakthrough decided the entire cam we pointed out two remarkable facts. viz.• paign. Another wave of US troop. advanoe!l I (1) that only one major landing operation had east from Granville to Villedieu to CO-<lperate been carried out during the first six weeks, and with formatioJlB furt,her t.o the northeast ill (2) that the number of troops pumped into the protecting the left Bank of the main thruli,. comparatively narrow bridgehead was out of Several German attacks against this flank in the proportion to the area then at the disposal of the area of Tessy. VilJedieu. and Mortain. which u Allied Command. Although this seemed to indicate one time narrowed the American corridor of that General Eisenhower intended to concentrate Avranches to twenty kilometers. had to be aban. all hi' available forces for a push from this one doned, as the sout.hward advance of the Britilh bridgehead. the German High Command could not 2nd Army from the region of Caumont threatened be sure of that and had therefore to maintain con· the rear of the German divisioJlB. The fate of the siderable forces all along the far·Bung coasts of campaign in FTance was sealed: what was at stake Europe. a factor which limited the forces opposing now was no longer tbe fat.e of French territory the Normandy invaders and gave the Allies a vast but that of the German armiCl in France. -

Military Tribunal, Indictments

MILITARY TRIBUNALS Case No. 12 THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA -against- WILHELM' VON LEEB, HUGO SPERRLE, GEORG KARL FRIEDRICH-WILHELM VON KUECHLER, JOHANNES BLASKOWITZ, HERMANN HOTH, HANS REINHARDT. HANS VON SALMUTH, KARL HOL LIDT, .OTTO SCHNmWIND,. KARL VON ROQUES, HERMANN REINECKE., WALTERWARLIMONT, OTTO WOEHLER;. and RUDOLF LEHMANN. Defendants OFFICE OF MILITARY GOVERNMENT FOR GERMANY (US) NORNBERG 1947 • PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/c6a171/ TABLE OF CONTENTS - Page INTRODUCTORY 1 COUNT ONE-CRIMES AGAINST PEACE 6 A Austria 'and Czechoslovakia 7 B. Poland, France and The United Kingdom 9 C. Denmark and Norway 10 D. Belgium, The Netherland.; and Luxembourg 11 E. Yugoslavia and Greece 14 F. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics 17 G. The United states of America 20 . , COUNT TWO-WAR CRIMES AND CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: CRIMES AGAINST ENEMY BELLIGERENTS AND PRISONERS OF WAR 21 A: The "Commissar" Order , 22 B. The "Commando" Order . 23 C, Prohibited Labor of Prisoners of Wal 24 D. Murder and III Treatment of Prisoners of War 25 . COUNT THREE-WAR CRIMES AND CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: CRIMES AGAINST CIVILIANS 27 A Deportation and Enslavement of Civilians . 29 B. Plunder of Public and Private Property, Wanton Destruc tion, and Devastation not Justified by Military Necessity. 31 C. Murder, III Treatment and Persecution 'of Civilian Popu- lations . 32 COUNT FOUR-COMMON PLAN OR CONSPIRACY 39 APPENDIX A-STATEMENT OF MILITARY POSITIONS HELD BY THE DEFENDANTS AND CO-PARTICIPANTS 40 2 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/c6a171/ INDICTMENT -

The Durham Light Infantry and the Somme 1916

The Durham Light Infantry and The Somme 1916 by John Bilcliffe edited and amended in 2016 by Peter Nelson and Steve Shannon Part 4 The Casualties. Killed in Action, Died of Wounds and Died of Disease. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License You can download this work and share it with others as long as it is credited, but you can’t change it in any way or use it commercially © John Bilcliffe. Email [email protected] Part 4 Contents. 4.1: Analysis of casualties sustained by The Durham Light Infantry on the Somme in 1916. 4.2: Officers who were killed or died of wounds on the Somme 1916. 4.3: DLI Somme casualties by Battalion. Note: The drawing on the front page of British infantrymen attacking towards La Boisselle on 1 July 1916 is from Reverend James Birch's war diary. DCRO: D/DLI 7/63/2, p.149. About the Cemetery Codes used in Part 4 The author researched and wrote this book in the 1990s. It was designed to be published in print although, sadly, this was not achieved during his lifetime. Throughout the text, John Bilcliffe used a set of alpha-numeric codes to abbreviate cemetery names. In Part 4 each soldier’s name is followed by a Cemetery Code and, where known, the Grave Reference, as identified by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Here are two examples of the codes and what they represent: T2 Thiepval Memorial A5 VII.B.22 Adanac Military Cemetery, Miraumont: Section VII, Row B, Grave no. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Back-Roads| Europe

WWI BATTLEFIELDS Blue-Roads | Europe This fascinating and moving tour focuses on the major areas of British and Commonwealth involvement across the Western Front – from The Somme to Flanders. Providing guests with a level of flexibility to visit memorials to his (or her) country’s fallen, and the expert knowledge of our Tour Leaders – this tour promises to be as unforgettable as it is enlightening. TOUR CODE: BEWBFLL-1 Thank You for Choosing Blue-Roads Thank you for choosing to travel with Back-Roads Touring. We can’t wait for you to join us on the mini-coach! About Your Tour Notes THE BLUE-ROADS DIFFERENCE Have the opportunity to pay your respects at your relatives’ graves with These tour notes contain everything you need to know visits to significant sites before your tour departs – including where to meet, Receive a fascinating insight into the what to bring with you and what you can expect to do lives of WWI soldiers at the on each day of your itinerary. You can also print this Underground City of Naours document out, use it as a checklist and bring it with you Attend the playing of the Last Post on tour. under the famous Menin Gate in Ypres Please Note: We recommend that you refresh this document one week before your tour TOUR CURRENCIES departs to ensure you have the most up-to-date accommodation list and itinerary information + France - EUR available. + Belgium - EUR Your Itinerary DAY 1 | LILLE After meeting the group in Lille, we’ll kick off our battlefields tour with a delicious welcome dinner.