AZERBAIJAN in the WORLD ADA Biweekly Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief Analysis of the Situation in South Caucasus

Brief Analysis of the Situation in South Caucasus Jimsher Jaliashvili, Professor Grigol Robakidze University, Tbilisi, Georgia Anna Shah, Master’s programme student Grigol Robakidze University, Tbilisi, Georgia Abstract Despite its small size and relatively small population, the South Caucasus occupies an important place in international geopolitics. Region is an important link between East and West that makes the world actors to give great attention to developing a strategy towards the region in order to maximize meaning of own presence in this important geo-strategic area. Above mentioned factors could contribute to the integration of the region for more effective joint action on the world scene as a union. However, to date, this bone of contention is a zone of low-intensity conflicts, the so-called "frozen conflicts" that threaten to "unfreeze" at any time. After the collapse of the Soviet Union over its entire territory ethnic conflicts became flare up. Some of them spilled over into the active full-scale wars. This is what happened in the South Caucasus in the regions of South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Nagorno-Karabakh. These conflicts still remain a stumbling block to normalization of relations of the Caucasian neighbor countries. I. The practice of international life continues to destroy the remnants of illusions associated with the Cold War and the collapse of the bipolar configuration of the world1. Fukuyama's theory2 turned out to be insolvent and the multipolar world living in tolerance for the cultures and customs of each other, respecting the framework of law and morality, and solving ethnic conflict only walking in line of negotiation is just a good, distant fairy tale, an unattainable myth. -

1 ...The Khojaly Massacre Is a Bloody Episode. It Is a Continuation of The

...The Khojaly massacre is a bloody episode. It is a continuation of the ethnic cleansing and genocide policies that the Armenian chauvinist-nationalists have been progressively carrying out against the Azerbaijanis for approximately 200 years. These accursed policies, supported by the authorities of some states, were constantly pursued by Tsarist Russia and the Soviets. After the demise of the USSR these policies led to the displacement of Azerbaijanis from their homelands, exposing them to suffering on a massive scale. In all, two million Azerbaijanis have at various times felt the weight of the policies of ethnic cleansing and genocide pursued by aggressive Armenian nationalists and stupid ideologues of "Greater Armenia". ...Today the Government of Azerbaijan and its people must bring the truth about the Khojaly genocide and all the Armenian atrocities in Nagorny Karabakh, their scale and brutality, to the countries of the world, their parliaments and the public at large and achieve the recognition of these atrocities as an act of genocide. This is the humane duty of every citizen before the spirits of the Khojaly martyrs. An international legal and political assessment of the tragedy and proper punishment of the ideologues, organizers and executors are important in order to avoid in future such barbarous acts against humanity as a whole... Heydar Aliyev President of the Republic of Azerbaijan 25 February 2002 1 Background 7 Mass Media 13 The Washington Post, The Independent, The Sunday Times, The Times, The Washington Times, The New -

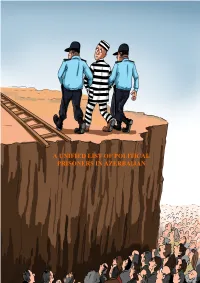

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

The Nagorno Karabakh Conflict and the Crisis in Turkey's Domestic

INSTITUTE FOR SECURITY POLICY (ISP) WORKING PAPER THE NAGORNO KARABAKH CONFLICT AND THE CRISIS IN TURKEY'S DOMESTIC POLITICS by Arif ASALIOGLU International Institute of the Development of Science Cooperation (MIRNAS) VIENNA 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 3 II. ISOLATION LED ANKARA TO THE KARABAKH CRISIS ............................................................................. 6 III. THE ERDOGAN REGIME CONTINUES TO PLAY WITH FIRE AND TO SPREAD FIRE AROUND ITSELF .... 9 IV. “WE SENT MILITANTS TO AZERBAIJAN.” ................................................................................................. 11 V. MOST OF THE TIME IS WASTED ................................................................................................................ 12 VI. RUSSIA AND TURKEY MAY HAVE STRONG DISAGREEMENT ................................................................ 14 VII. CONCLUSION: THE RISK OF CONFRONTATION BETWEEN RUSSIA AND TURKEY ................................ 16 1 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Arif Asalioglu is General Director of the International Institute of the Development of Science Cooperation (MIRNAS). Graduated from the faculty of foreign languages of the Kyiv State Linguistic University. From 2011 to 2014, General Director of the Turkish-Russian Cultural Center, Moscow. Since 2014, General Director of the International Institute for the development of Science Cooperation in Moscow; -

The South Caucasus 2018

THE SOUTH CAUCASUS 2018 FACTS, TRENDS, FUTURE SCENARIOS Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) is a political foundation of the Federal Republic of Germany. Democracy, peace and justice are the basic principles underlying the activities of KAS at home as well as abroad. The Foundation’s Regional Program South Caucasus conducts projects aiming at: Strengthening democratization processes, Promoting political participation of the people, Supporting social justice and sustainable economic development, Promoting peaceful conflict resolution, Supporting the region’s rapprochement with European structures. All rights reserved. Printed in Georgia. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Regional Program South Caucasus Akhvlediani Aghmarti 9a 0103 Tbilisi, Georgia www.kas.de/kaukasus Disclaimer The papers in this volume reflect the personal opinions of the authors and not those of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation or any other organizations, including the organizations with which the authors are affiliated. ISBN 978-9941-0-5882-0 © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V 2013 Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................ 4 CHAPTER I POLITICAL TRANSFORMATION: SHADOWS OF THE PAST, FACTS AND ANTICIPATIONS The Political Dimension: Armenian Perspective By Richard Giragosian .................................................................................................. 9 The Influence Level of External Factors on the Political Transformations in Azerbaijan since Independence By Rovshan Ibrahimov -

Forging the Future of the Caucasus: the Past 20 Years and Its Lessons

Forging the future of the Caucasus: The past 20 years and its lessons Post-Conference Evaluation Report Forging the future of the Caucasus: The past 20 years and its lessons Post-Conference Evaluation Report Baku, Azerbaijan 2012 Joint Publication of Caucasus International (CI), Center for Strategic Studies (SAM) and Turkish Policy Quarterly (TPQ) Design/Production: Osman Balaban Printed by Moda Ofset Basım Yayın San.Tic.Ltd.Şti. Istanbul, Turkey All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be copied, redistributed, or published without express permission in writing from the publisher. The views reflected here are purely personal and do not represent the views of CI, SAM, or TPQ. CONTENTS Conference Organizers and Panelists 4 Introduction 6 Opening Remarks 7 Key Debates 1. Change and Continuity of Independence 8 2. Astronomic Expectations vs. Earthly Realities 10 3. South Caucasus: a malfunctioning region? 12 4. Small States and Big Neighbors – The Question of Alignments 15 5. Boundaries and Barriers: Relations with Neighbors 19 Summary: Highlights from the Speakers 27 Post-Conference Evaluation Report Conference Organizers and Panellists Center for Strategic Studies (SAM) The Center for Strategic Studies (www.sam.gov.az) is Azer- baijan’s first government-funded, non-profit and academically independent think tank, known as SAM (Strateji Araşdırmalar Mərkəzi in Azerbaijani). The mission of SAM is to promote collaborative research and enhance the strategic debate as well as providing decision-makers with high-quality analysis and innovative proposals for action. Through publications, brain- storming meetings, conferences and policy recommendations, SAM conducts rigorous research guided by a forward-looking policy orientation, thus bringing new perspectives to strategic discussions and contributing to informed decision making in Azerbaijan Turkish Policy Quarterly (TPQ) Turkish Policy Quarterly (www.turkishpolicy.com) is an Istan- bul-based journal published on a quarterly basis since 2002. -

1998 Presidential Election in Azerbaijan

COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE 234 FORD HOUSE OFFICE BUILDING WASHINGTON, DC 20515 (202) 225-1901 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] INTERNET WEB SITE: http://www.house.gov/csce REPORT ON AZERBAIJAN’S PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION Baku, Sumgait, Ganja A Report Prepared by the Staff of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe December 1998 Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe 234 Ford House Office Building Washington, DC 20515-6460 (202) 225-1901 [email protected] http://www.house.gov/csce/ ALFONSE D’AMATO, New York, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, Co-Chairman JOHN EDWARD PORTER, Illinois BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado FRANK R. WOLF, Virginia SPENCER ABRAHAM, Michigan MATT SALMON, Arizona CONRAD BURNS, Montana JON CHRISTENSEN, Nebraska OLYMPIA SNOWE, Maine STENY H. HOYER, Maryland FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts HARRY REID, Nevada BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland BOB GRAHAM, Florida LOUISE MCINTOSH SLAUGHTER, New York RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin Executive Branch HON. JOHN H. F. SHATTUCK, Department of State VACANT, Department of Defense VACANT, Department of Commerce ________________________ Professional Staff MICHAEL R. HATHAWAY, Chief of Staff DOROTHY DOUGLAS TAFT, Deputy Chief of Staff MARIA COLL, Office Administrator OREST DEYCHAKIWSKY, Staff Advisor JOHN FINERTY, Staff Advisor CHADWICK R. GORE, Communications Director ROBERT HAND, Staff Advisor JANICE HELWIG, Staff Advisor (Vienna) MARLENE KAUFMANN, Counsel for International Trade SANDY LIST, GPO Liaison KAREN S. LORD, Counsel for Freedom of Religion RONALD MCNAMARA, Staff Advisor MICHAEL OCHS, Staff Advisor ERIKA B. SCHLAGER, Counsel for International Law MAUREEN WALSH, Counsel for Property Rights ii ABOUT THE ORGANIZATION (OSCE) The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, also known as the Helsinki pro- cess, traces its origin to the signing of the Helsinki Final Act in Finland on August 1, 1975, by the leaders of 33 European countries, the United States and Canada. -

Annual Report Annual Report 2019 Content Abbreviations

ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CONTENT ABBREVIATIONS 1. ABOUT SOFAZ . 6 ACG - Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli AIOC - Azerbaijan International Operating Company 2. FACTS AT A GLANCE . 10 BOE - The Bank of England CBAR - The Central Bank of the Republic of Azerbaijan 3. GOVERNANCE AND TRANSPARENCY . 12 ECB - European Central Bank 3.1. MANAGEMENT OF SOFAZ . 12 FED - The Federal Reserve 3.2. TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY . 16 GDP - Gross Domestic Product IFSWF - The International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds 4. NATIONAL ECONOMY AND SOFAZ . 17 IMF - The International Monetary Fund 4.1. MACROECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT . 17 OPEC - Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries 4.2. SOFAZ’S REVENUES . 26 PSA - Production Sharing Agreement 4.3. SOFAZ’S EXPENDITURES . 30 SCCA - State Customs Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan SGC - Southern Gas Corridor 5. INVESTMENTS . 36 SOFAZ - The State Oil Fund of the Republic of Azerbaijan 5.1. INVESTMENT STRATEGY . 36 SSC - The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan 5.2. SOFAZ’S INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO . 39 VAR - Value at Risk 5.3. SOFAZ’S INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO PERFORMANCE . 55 WB - The World Bank 5.4. RISK MANAGEMENT . 57 6. 2019 SOFAZ BUDGET EXECUTION . 62 7. CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF SOFAZ . 68 APPENDIX . 126 ABOUT SOFAZ 1. ABOUT SOFAZ OUR VALUES Integrity September 20, 1994 marked a significant milestone in 1. Supporting macroeconomic stability, participating We conduct our activity in accordance with the highest moral standards and ethical principles of society. We are honest the history of modern Azerbaijan. Under the leadership in ensuring fiscal-tax discipline and decreasing and truthful in all our words and actions. -

Time for Armenian and Azerbaijani Diasporas to Talk to Each Other

Time for Armenian and Azerbaijani diasporas to talk to each other https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article6936 Nagorno-Karabakh Time for Armenian and Azerbaijani diasporas to talk to each other - IV Online magazine - 2020 - IV551 - December 2020 - Publication date: Tuesday 8 December 2020 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/4 Time for Armenian and Azerbaijani diasporas to talk to each other The 2018 changes in Armenia did not produce any revolutionary discourse concerning the Karabakh conflict. In Yerevan as in Baku, political elites do not seem able to imagine how to resolve this conflict. I call Diaspora Armenians and Azerbaijanis living abroad to make a bold initiative and start a new dialogue, may be they could move a process that is central in determining the future of their homelands, yet remains paralyzed for nearly two decades. It was 20 years ago, in June 1999, when I went to Baku with a group of journalists from Armenia, Karabakh, and Georgia. It was part of a project I had initiated in 1997 where I wanted to offer journalists in the South Caucasus a chance to see "to the other side" of the conflict line, to meet and exchange with colleagues and politicians of their neighbouring countries. Weren't they members of the same Soviet Union, I thought? By knowing the concerns, fears and hopes of the other, journalists could propose a more nuanced reporting, and therefore influence the public opinion towards mutual understanding and eventually contributed to conflict resolution. Our visit to Baku was the result of efforts of several years. -

NATO and the South Caucasus: Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia on Different Tracks Martin Malek *

NATO and the South Caucasus: Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia on Different Tracks Martin Malek * Introduction In 2002, NATO Secretary-General Lord George Robertson stated that, “for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the Caucasus is of no special relevance.”1 Up until now, this attitude has not changed fundamentally, even though the region obviously attracts the Alliance’s attention more than it did in the 1990s. NATO’s stance toward the South Caucasus has always provoked much more and stronger reactions in Russia than in the political, media, and public realms of the Alliance’s member states. In 1999, within the framework of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC), an Ad Hoc Working Group on Prospects for Regional Cooperation in the Caucasus was established, placing primary focus on defense and economics issues, civil and emergency planning, science and environmental cooperation, and information activi- ties. However, to date there is no overall comprehensive format for NATO cooperation with the South Caucasus that would even come close to its “strategic partnership” with the EU, its concept of “special relations” with Russia and Ukraine, the Mediterranean Dialogue, or the South East European Initiative. Only in 2004—i.e., a full thirteen years after the dissolution of the USSR, which was closely followed by the independ- ence of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia—U.S. diplomat Robert Simmons was ap- pointed as NATO’s first Special Envoy for the South Caucasus and Central Asia. The prospects for joint initiatives with NATO are inevitably negatively influenced by the fact that the armies of all South Caucasian republics are far from meeting NATO standards and requirements, even though especially Georgia and Azerbaijan have been declaring that they hope to introduce and achieve these standards sooner rather than later. -

Black Garden : Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War / Thomas De Waal

BLACK GARDEN THOMAS DE WAAL BLACK GARDEN Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War a New York University Press • New York and London NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London © 2003 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data De Waal, Thomas. Black garden : Armenia and Azerbaijan through peace and war / Thomas de Waal. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8147-1944-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict, 1988–1994. 2. Armenia (Republic)— Relations—Azerbaijan. 3. Azerbaijan—Relations—Armenia (Republic) I. Title. DK699.N34 D4 2003 947.54085'4—dc21 2002153482 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America 10987654321 War is kindled by the death of one man, or at most, a few; but it leads to the death of tremendous numbers. —Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power Mercy on the old master building a bridge, The passer-by may lay a stone to his foundation. I have sacrificed my soul, worn out my life, for the nation. A brother may arrange a rock upon my grave. —Sayat-Nova Contents Author’s Note ix Two Maps, of the South Caucasus and of Nagorny Karabakh xii–xiii. Introduction: Crossing the Line 1 1 February 1988: An Armenian Revolt 10 2 February 1988: Azerbaijan: Puzzlement and Pogroms 29 3 Shusha: The Neighbors’ Tale 45 4 1988–1989: An Armenian Crisis 55 5 Yerevan: Mysteries of the East 73 6 1988–1990: An Azerbaijani Tragedy 82 7 -

The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Obstacles and Opportunities for a Settlement

The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Obstacles and Opportunities for a Settlement Chanda Allana Leckie Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts In Political Science Charles Taylor, Chair Scott Nelson Edward Weisband May 04, 2005 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: OSCE Minsk Group, geopolitics, conflict settlement The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Obstacles and Opportunities for a Settlement Chanda Allana Leckie Abstract----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Out of the violent conflicts in the former Soviet Union, the war over Nagorno- Karabakh is the most threatening to the future development of the region, both economically and politically, as it is no closer to a solution than when the fighting ended in 1994. This is regrettable as there are some opportunities that provide the warring parties enough flexibility to move forward in the negotiation process. This thesis analyzes the evolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict under the aegis of the OSCE Minsk Group from 1992 to the present. It discusses not only the history of the Nagorno- Karabakh conflict and what went wrong with the Minsk Group’s attempts to find a fair and objective solution to the conflict, but also the obstacles and opportunities for a settlement. From this discussion, suggestions to improve the Minsk Group’s performance are presented, and future predictions of a peaceful settlement to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict will also be discussed. Acknowledgements------------------------------------------------------------------------- I wish to thank my committee chair Dr. Charles Taylor for his guidance, support, and collaboration on this thesis and throughout my time at Virginia Tech.