“Frozen Conflicts” in Europe Anton Bebler (Ed.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Analytical Digest No 40: Russia and the "Frozen Conflicts" Of

No. 40 8 May 2008 rrussianussian aanalyticalnalytical ddigestigest www.res.ethz.ch www.laender-analysen.de/russland RUSSIA AND THE “FROZEN CONFLICTS” OF GEORGIA ■ ANALYSIS Georgia’s Secessionist De Facto States: From Frozen to Boiling 2 By Stacy Closson, Zurich ■ ANALYSIS A Russian Perspective: Forging Peace in the Caucasus 5 By Sergei Markedonov, Moscow ■ OPINION POLL Russian Popular Opinion Concerning the Frozen Confl icts on the Territory of the Former USSR 9 ■ ANALYSIS A Georgian Perspective: Towards “Unfreezing” the Georgian Confl icts 12 By Archil Gegeshidze, Tbilisi ■ ANALYSIS An Abkhaz Perspective: Abkhazia after Kosovo 14 By Viacheslav Chirikba, Sukhumi / Leiden Research Centre for East Center for Security Otto Wolff -Stiftung DGO European Studies, Bremen Studies, ETH Zurich rrussianussian aanalyticalnalytical russian analytical digest 40/08 ddigestigest Analysis Georgia’s Secessionist De Facto States: From Frozen to Boiling By Stacy Closson, Zurich Abstract Relations between Russia and Georgia have reached a new low. At the center of their quarrel are Georgia’s secessionist regions, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. As Russia and Georgia accuse the other of troop move- ments in and around the secessionist territories, the UN, EU, OSCE, and NATO meet to determine their response. Critical to these deliberations are several underlying developments, which would benefi t from an independent review. Th ese include economic blockades of the secessionist territories, Russia’s military sup- port for the secessionists, the issuance of Russian passports to secessionist residents, and declarations of in- dependence by secessionist regimes. In these circumstances, it has become diffi cult to contain the confl icts without resolving them. However, as confl ict resolution has proven impracticable, it is time to consider al- tering present arrangements in order to prevent an escalation of violence. -

From an Autonomous Province to a Habsburg Principality

FROM AN AUTONOMOUS PROVINCE TO A HABSBURG PRINCIPALITY. THE LEGISLATIVE ROLE OF THE TRANSYLVANIAN DIET DURING THE 18TH CENTURY Gelu Fodor* Keywords: Werböczy, Tripartitum, constitution, Diet, Pragmatic Sanction, legislative system Cuvinte cheie: Werböczy, Tripartitum, constituţie, dietă, Pragmatica Sancţiune, sistem legislativ Introductory considerations Our approach aims to shed light on the evolution of the Transylvanian constitution and constitutionalism after the incorporation of the Principality of Transylvania within the administrative structures of the Habsburg Empire, the upper chronological limit being the provisions the Diet issued in 1791. In order to achieve this goal, we intend to examine all the aspects that contributed decisively to shaping the constitutional realities in the Principality, focusing in particular on the institutional and legislative role of the Diet, as a representative authority for the nobility in its relationship with the Habsburg sovereigns. The conquest of Transylvania by the Habsburgs gradually brought about major changes as regards the law-making institutions, and some of these changes were made with the direct involvement of the Diet. The central aspect on which we shall dwell and which, in our opinion, was the quintessence of the entire legislative process unfolding throughout the 18th century, revolved around the articles of law enacted by the Diet of 1744 and, respectively, of the Diet of 1791. By analysing their specific provisions, we shall attempt to highlight the changes that took place in the constitutional structure of the Principality up until the turn of the 19th century. Another point of interest for our study revolves around what certain historians regard as the very foundation of the Transylvanian political system, namely the Constitutions of Transylvania: Werböczy’s Tripartitum, Aprobatae Constitutiones and Compilatae Constitutiones. -

Complete Issue

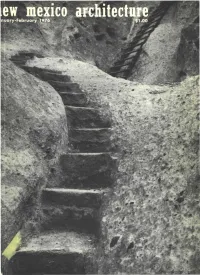

Conerete Bloek & Sprayed Coating- a ~inning eOlDbination of beauty & silDplieity at lo~eost STAND RD CREGO CK WITH CEMENT LE E COAT AND SPRAYED-ON TE U ED INISH COAT • JERRY GOFFE PHOTO RUST TRACTOR COMPANY ELLISON-HAWKINS-VOGT 6' BYRNES, P.A. ARCH ITECTS ·ENGINEERS K. L. HOUSE CONSTRUCTION CO. GENERAL CONTRACTOR KENNETH P. THOMPSON CO., INC. MASONRY CONTRACTOR BILL C. CARROLL CO., INC. SPRAYED COATING "'\ For our reoders I"~, we wish 1976 to \'\'~" be rhapsodic, • thriving, abundant and eudaemonic. , '~-I4 ""_ """""' .----"''''''v~J col: 18 no. 1 jan. - feb. 1976 • new mexico architecture As we begin another year of New Mexico Architecture, it is appropri ate to remind our readers of the contribution made to our financial stability by the advertisers. It is their support which makes possible the production of the magazine. To all of these fine people the "staff" says a most sincere thank you! Space in New Mexico Architecture o DOD as a Resource for on Energy Ethic 10 Beginning on page lOis an arti - By Anthony C. Antoniades, AI.A, AI.P. cle by Anthony C. Antoniades, AlA, AlP, Associate Professor of Archi tecture at the University of Texas at Arlington. Professor Antoniades taught architecture at the Universi ty of New Mexico before moving to Index to Advertisers 18 Texas. It was during those years in our state that he developed a strong interest in and knowledge of the architectural heritage of New Mexi ico. Three articles by Antoniades hove appeared previously in NMA November/December 1971, Septem ber/October 1973 and July/August 1974. -

Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia

Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia Niklas Nilsson SILK ROAD PAPER January 2018 Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia Niklas Nilsson © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program – A Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center American Foreign Policy Council, 509 C St NE, Washington D.C. Institute for Security and Development Policy, V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.silkroadstudies.org “Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia” is a Silk Road Paper published by the Central Asia- Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program, Joint Center. The Silk Road Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Joint Center, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Joint Center is a transatlantic independent and non-profit research and policy center. It has offices in Washington and Stockholm and is affiliated with the American Foreign Policy Council and the Institute for Security and Development Policy. It is the first institution of its kind in Europe and North America, and is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. The Joint Center is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development in the region. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion regarding the region. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this study are those of -

Statement by Herman Van Rompuy President of the European Council Following His Meeting with Atifete Jahjaga President of Kosovo

EUROPEAN COUNCIL THE PRESIDENT EN Brussels, 6 September 2011 EUCO 66/11 PRESSE 298 PR PCE 39 Statement by Herman Van Rompuy President of the European Council following his meeting with Atifete Jahjaga President of Kosovo I am pleased to welcome President Jahjaga in Brussels today. Her visit takes place only a few days after the latest round of the Pristina - Belgrade dialogue, so allow me to start on that topic. Let me emphasise that the EU is very satisfied with the latest agreements on Customs Stamps and Cadastre. The agreements reached last Friday are truly European solutions to some very difficult issues. In particular, the agreement on customs stamps is crucial, since it will result in the lifting of the mutual trade embargoes. This is a significant step in improving relations in the region and ensuring freedom of movement of goods in accordance with European values and standards. However, there is more to do. Discussions need to continue and further progress needs to be made on the remaining issues. We need to find equally creative and pragmatic solutions for the issues of telecommunication, energy, and representation in regional fora. Dialogue, compromise and consensus seeking are the European way. Both sides have everything to gain from these deals, as the aim of this dialogue is to bring both sides closer to the EU, to improve mutual cooperation, and to improve the lives of ordinary people. This brings me to the other topic of our discussion today, namely the relations between the European Union and Kosovo, and related developments in Kosovo itself. -

Georgia Case Study Part II: Internally Displaced Persons Viewed Externally

Georgia Case Study Part II: Internally Displaced Persons Viewed Externally Brian Frydenborg Experiential Applications – MNPS 703 Allison Frendak-Blume, Ph.D. The problem of internally displaced persons (referred to commonly as IDPs) and international refugees is as old as the problem of war itself. As a special report of The Jerusalem Post notes, “Wars produce refugees” (Radler n.d., par. 1). The post-Cold-War conflicts in Georgia between Georgia, Russian, and Georgia‟s South Ossetia and Abkhazia regions displaced roughly 223,000 people, mostly from the Abkhazia part of the conflict, and the recent fighting between Georgia and Russia/South Ossetia/Abkhazia of August 2008 created 127,000 such IDPs and refugees (UNHCR 2009a, par. 1). A United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) mission even before the 2008 fighting “described the needs of Georgia's displaced as „overwhelming‟” (Ibid., par. 2). This paper will discuss the problem of IDPs in Georgia, particularly as related to the Abkhazian part of the conflicts of the last few decades. It will highlight the efforts of one international organization (IO), the UNHCR, and one non-governmental organization (NGO), the Danish Refugee Council. i. Focus of Paper and Definitions The UN divides people as uprooted by conflict into two categories: refugees and internally displaced persons; the first group refers to people who are “forcibly uprooted” and flee from their nation to another, the second to people who are “forcibly uprooted” and flee to another location within their nation (UNHCR 2009b, par 1). Although there are also IDPs and refugees resulting from the fighting in South Ossetia, this paper will focus on the IDPs from the fighting in and around Abkhazia; refugees from or in Georgia will not be dealt with specifically because the overwhelming majority of people uprooted from their homes in relation to Georgia‟s ethnic conflicts ended up being IDPs (close to 400,000 total current and returned) and less than 13,000 people were classified as refugees from these conflicts (UNHCR 2009a, par. -

Exploring the Link Between Power Concentration and Ethnic Minorities’ Mobilization in Post Soviet Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine

Exploring the Link between Power Concentration and Ethnic Minorities’ Mobilization in Post Soviet Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine by Stela Garaz Department of Political Science, Central European University A Doctoral Dissertation submitted to the Central European University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date of submission: April 30, 2012 Supervisor: Dr. Zsolt Enyedi Budapest, Hungary 2012 I hereby declare that this thesis contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. I hereby declare that this thesis contains no materials previously written and/or published by any other person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Stela Garaz Budapest April 30, 2012. ii Abstract In political science literature, power concentration is dominantly viewed as a negative phenomenon that encourages strategies of confrontation and causes protest. The regimes with concentrated power are believed to be particularly dangerous for the states with deep ethnic cleavages. This latter concern is a question of great importance for the post-Soviet region, because since the collapse of the Soviet Union some of the multi-ethnic post-Soviet states had the experience of both ethnic conflicts and concentration of power. Consequently, the main goal of this research is to determine whether power concentration encourages the escalation of ethnic conflicts. For this, I explore three mechanisms that may link the degree of power concentration with ethnic minorities’ mobilization against the state: identity-related state policies, electoral rules, and centralization. The empirical investigation is built on the analysis of three post-Soviet cases – Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine – based on the structured focused comparison technique. -

List of Subjects, Admission of New Subjects Article 66

Chapter 3. Federative Arrangement (Articles 65–79) 457 Chapter 3. Federative Arrangement See also Art.5 Federative arrangement Article 65: List of subjects, admission of new subjects Art.65.1. The composition of the RF comprises the following RF subjects: the Republic Adygeia (Adygeia), the Republic Altai, the Republic Bashkortostan, the Republic Buriatia, the Republic Dagestan, the Republic Ingushetia, the Kabarda-Balkar Republic, the Republic Kalmykia, the Karachai-Cherkess Republic, the Republic Karelia, the Republic Komi, the Republic Mari El, the Republic Mordovia, the Republic Sakha (Iakutia), the Republic North Ossetia- Alania, the Republic Tatarstan (Tatarstan), the Republic Tyva, the Udmurt Republic, the Republic Khakasia, the Chechen Republic, and the Chuvash Republic-Chuvashia; Altai Territory, Krasnodar Territory, Krasnoiarsk Territory, Primor’e Territory, Stavropol’ Territory, and Khabarovsk Territory; Amur Province, Arkhangel’sk Province, Astrakhan’ Province, Belgorod Province, Briansk Province, Vladimir Province, Volgograd Province, Vologda Province, Voronezh Province, Ivanovo Province, Irkutsk Province, Kaliningrad Province, Kaluga Province, Kamchatka Province, Kemerovo Province, Kirov Province, Kostroma Province, Kurgan Province, Kursk Province, Leningrad Province, Lipetsk Province, Magadan Province, Moscow Province, Murmansk Province, Nizhnii Novgorod Province, Novgorod Province, Novosibirsk Province, Omsk Province, Orenburg Province, Orel Province, Penza Province, Perm’ Province, Pskov Province, Rostov Province, Riazan’ -

Annual Report

Greeks Helping Greeks ANNUAL REPORT 2019 About THI The Hellenic Initiative (THI) is a global, nonprofi t, secular institution mobilizing the Greek Diaspora and Philhellene community to support sustainable economic recovery and renewal for Greece and its people. Our programs address crisis relief through strong nonprofi t organizations, led by heroic Greeks that are serving their country. They also build capacity in a new generation of heroes, the business leaders and entrepreneurs with the skills and values to promote the long term growth of Hellas. THI Vision / Mission Statement Investing in the future of Greece through direct philanthropy and economic revitalization. We empower people to provide crisis relief, encourage entrepreneurs, and create jobs. We are The Hellenic Initiative (THI) – a global movement of the Greek Diaspora About the Cover Featuring the faces of our ReGeneration Interns. We, the members of the Executive Committee and the Board of Directors, wish to express to all of you, the supporters and friends of The Hellenic Initiative, our deepest gratitude for the trust and support you have given to our organization for the past seven years. Our mission is simple, to connect the Diaspora with Greece in ways which are valuable for Greece, and valuable for the Diaspora. One of the programs you will read about in this report is THI’s ReGeneration Program. In just 5 years since we launched ReGeneration, with the support of the Coca-Cola Co. and the Coca-Cola Foundation and 400 hiring partners, we have put over 1100 people to work in permanent well-paying jobs in Greece. -

ON the EFFECTIVE USE of PROXY WARFARE by Andrew Lewis Peek Baltimore, Maryland May 2021 © 2021 Andrew Peek All Rights Reserved

ON THE EFFECTIVE USE OF PROXY WARFARE by Andrew Lewis Peek A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland May 2021 2021 Andrew Peek All rights reserved Abstract This dissertation asks a simple question: how are states most effectively conducting proxy warfare in the modern international system? It answers this question by conducting a comparative study of the sponsorship of proxy forces. It uses process tracing to examine five cases of proxy warfare and predicts that the differentiation in support for each proxy impacts their utility. In particular, it proposes that increasing the principal-agent distance between sponsors and proxies might correlate with strategic effectiveness. That is, the less directly a proxy is supported and controlled by a sponsor, the more effective the proxy becomes. Strategic effectiveness here is conceptualized as consisting of two key parts: a proxy’s operational capability and a sponsor’s plausible deniability. These should be in inverse relation to each other: the greater and more overt a sponsor’s support is to a proxy, the more capable – better armed, better trained – its proxies should be on the battlefield. However, this close support to such proxies should also make the sponsor’s influence less deniable, and thus incur strategic costs against both it and the proxy. These costs primarily consist of external balancing by rival states, the same way such states would balance against conventional aggression. Conversely, the more deniable such support is – the more indirect and less overt – the less balancing occurs. -

Report Between the President and Constitutional Court and Its Influence on the Functioning of the Constitutional System in Kosovo Msc

Report between the President and Constitutional Court and its influence on the functioning of the Constitutional System in Kosovo MSc. Florent Muçaj, PhD Candidate Faculty of Law, University of Prishtina, Kosovo MSc. Luz Balaj, PhD Candidate Faculty of Law, University of Prishtina, Kosovo Abstract This paper aims at clarifying the report between the President and the Constitutional Court. If we take as a starting point the constitutional mandate of these two institutions it follows that their final mission is the same, i.e., the protection and safeguarding of the constitutional system. This paper, thus, will clarify the key points in which this report is expressed. Further, this paper examines the theoretical aspects of the report between the President and the Constitutional Court, starting from the debate over this issue between Karl Schmitt and Hans Kelsen. An important part of the paper will examine the Constitution of Kosovo, i.e., the contents of the constitutional norm and its application. The analysis focuses on the role such report between the two institutions has on the functioning of the constitutional system. In analyzing the case of Kosovo, this paper examines Constitutional Court cases in which the report between the President and the Constitutional Court has been an issue of review. Such cases assist us in clarifying the main theme of this paper. Therefore, the reader will be able to understand the key elements of the report between the President as a representative of the unity of the people on the one hand and the Constitutional Court as a guarantor of constitutionality on the other hand. -

Flags of Asia

Flags of Asia Item Type Book Authors McGiverin, Rolland Publisher Indiana State University Download date 27/09/2021 04:44:49 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/12198 FLAGS OF ASIA A Bibliography MAY 2, 2017 ROLLAND MCGIVERIN Indiana State University 1 Territory ............................................................... 10 Contents Ethnic ................................................................... 11 Afghanistan ............................................................ 1 Brunei .................................................................. 11 Country .................................................................. 1 Country ................................................................ 11 Ethnic ..................................................................... 2 Cambodia ............................................................. 12 Political .................................................................. 3 Country ................................................................ 12 Armenia .................................................................. 3 Ethnic ................................................................... 13 Country .................................................................. 3 Government ......................................................... 13 Ethnic ..................................................................... 5 China .................................................................... 13 Region ..................................................................