1998 Presidential Election in Azerbaijan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief Analysis of the Situation in South Caucasus

Brief Analysis of the Situation in South Caucasus Jimsher Jaliashvili, Professor Grigol Robakidze University, Tbilisi, Georgia Anna Shah, Master’s programme student Grigol Robakidze University, Tbilisi, Georgia Abstract Despite its small size and relatively small population, the South Caucasus occupies an important place in international geopolitics. Region is an important link between East and West that makes the world actors to give great attention to developing a strategy towards the region in order to maximize meaning of own presence in this important geo-strategic area. Above mentioned factors could contribute to the integration of the region for more effective joint action on the world scene as a union. However, to date, this bone of contention is a zone of low-intensity conflicts, the so-called "frozen conflicts" that threaten to "unfreeze" at any time. After the collapse of the Soviet Union over its entire territory ethnic conflicts became flare up. Some of them spilled over into the active full-scale wars. This is what happened in the South Caucasus in the regions of South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Nagorno-Karabakh. These conflicts still remain a stumbling block to normalization of relations of the Caucasian neighbor countries. I. The practice of international life continues to destroy the remnants of illusions associated with the Cold War and the collapse of the bipolar configuration of the world1. Fukuyama's theory2 turned out to be insolvent and the multipolar world living in tolerance for the cultures and customs of each other, respecting the framework of law and morality, and solving ethnic conflict only walking in line of negotiation is just a good, distant fairy tale, an unattainable myth. -

1 ...The Khojaly Massacre Is a Bloody Episode. It Is a Continuation of The

...The Khojaly massacre is a bloody episode. It is a continuation of the ethnic cleansing and genocide policies that the Armenian chauvinist-nationalists have been progressively carrying out against the Azerbaijanis for approximately 200 years. These accursed policies, supported by the authorities of some states, were constantly pursued by Tsarist Russia and the Soviets. After the demise of the USSR these policies led to the displacement of Azerbaijanis from their homelands, exposing them to suffering on a massive scale. In all, two million Azerbaijanis have at various times felt the weight of the policies of ethnic cleansing and genocide pursued by aggressive Armenian nationalists and stupid ideologues of "Greater Armenia". ...Today the Government of Azerbaijan and its people must bring the truth about the Khojaly genocide and all the Armenian atrocities in Nagorny Karabakh, their scale and brutality, to the countries of the world, their parliaments and the public at large and achieve the recognition of these atrocities as an act of genocide. This is the humane duty of every citizen before the spirits of the Khojaly martyrs. An international legal and political assessment of the tragedy and proper punishment of the ideologues, organizers and executors are important in order to avoid in future such barbarous acts against humanity as a whole... Heydar Aliyev President of the Republic of Azerbaijan 25 February 2002 1 Background 7 Mass Media 13 The Washington Post, The Independent, The Sunday Times, The Times, The Washington Times, The New -

The Nagorno Karabakh Conflict and the Crisis in Turkey's Domestic

INSTITUTE FOR SECURITY POLICY (ISP) WORKING PAPER THE NAGORNO KARABAKH CONFLICT AND THE CRISIS IN TURKEY'S DOMESTIC POLITICS by Arif ASALIOGLU International Institute of the Development of Science Cooperation (MIRNAS) VIENNA 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 3 II. ISOLATION LED ANKARA TO THE KARABAKH CRISIS ............................................................................. 6 III. THE ERDOGAN REGIME CONTINUES TO PLAY WITH FIRE AND TO SPREAD FIRE AROUND ITSELF .... 9 IV. “WE SENT MILITANTS TO AZERBAIJAN.” ................................................................................................. 11 V. MOST OF THE TIME IS WASTED ................................................................................................................ 12 VI. RUSSIA AND TURKEY MAY HAVE STRONG DISAGREEMENT ................................................................ 14 VII. CONCLUSION: THE RISK OF CONFRONTATION BETWEEN RUSSIA AND TURKEY ................................ 16 1 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Arif Asalioglu is General Director of the International Institute of the Development of Science Cooperation (MIRNAS). Graduated from the faculty of foreign languages of the Kyiv State Linguistic University. From 2011 to 2014, General Director of the Turkish-Russian Cultural Center, Moscow. Since 2014, General Director of the International Institute for the development of Science Cooperation in Moscow; -

The South Caucasus 2018

THE SOUTH CAUCASUS 2018 FACTS, TRENDS, FUTURE SCENARIOS Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) is a political foundation of the Federal Republic of Germany. Democracy, peace and justice are the basic principles underlying the activities of KAS at home as well as abroad. The Foundation’s Regional Program South Caucasus conducts projects aiming at: Strengthening democratization processes, Promoting political participation of the people, Supporting social justice and sustainable economic development, Promoting peaceful conflict resolution, Supporting the region’s rapprochement with European structures. All rights reserved. Printed in Georgia. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Regional Program South Caucasus Akhvlediani Aghmarti 9a 0103 Tbilisi, Georgia www.kas.de/kaukasus Disclaimer The papers in this volume reflect the personal opinions of the authors and not those of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation or any other organizations, including the organizations with which the authors are affiliated. ISBN 978-9941-0-5882-0 © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V 2013 Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................ 4 CHAPTER I POLITICAL TRANSFORMATION: SHADOWS OF THE PAST, FACTS AND ANTICIPATIONS The Political Dimension: Armenian Perspective By Richard Giragosian .................................................................................................. 9 The Influence Level of External Factors on the Political Transformations in Azerbaijan since Independence By Rovshan Ibrahimov -

Soviet Crackdown

CONFLICT IN THE SOVIET UNION Black January in Azerbaidzhan Human Rights Watch/Helsinki (formerly Helsinki Watch) The InterInter----RepublicRepublic Memorial Society CONFLICT IN THE SOVIET UNION Black January in Azerbaidzhan Human Rights Watch/Helsinki (formerly Helsinki Watch) The InterInter----RepublicRepublic Memorial Society Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London Copyright (c) May 1991 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN: 1-56432-027-8 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 91-72672 Human Rights Watch/Helsinki (formerly Helsinki Watch) Human Rights Watch/Helsinki was established in 1978 to monitor and promote domestic and international compliance with the human rights provisions of the 1975 Helsinki Accords. It is affiliated with the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, which is based in Vienna, Austria. Jeri Laber is the executive director; Lois Whitman is the deputy director; Holly Cartner and Julie Mertus are counsel; Erika Dailey, Rachel Denber, Ivana Nizich and Christopher Panico are research associates; Christina Derry, Ivan Lupis, Alexander Petrov and Isabelle Tin-Aung are associates; ðeljka MarkiÉ and Vlatka MiheliÉ are consultants. Jonathan Fanton is the chair of the advisory committee and Alice Henkin is vice chair. International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights Helsinki Watch is an affiliate of the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, a human rights organization that links Helsinki Committees in the following countries of Europe and North America: Austria, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, England, the Federal Republic of Germany, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, the Soviet Union, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United States, Yugoslavia. -

Forging the Future of the Caucasus: the Past 20 Years and Its Lessons

Forging the future of the Caucasus: The past 20 years and its lessons Post-Conference Evaluation Report Forging the future of the Caucasus: The past 20 years and its lessons Post-Conference Evaluation Report Baku, Azerbaijan 2012 Joint Publication of Caucasus International (CI), Center for Strategic Studies (SAM) and Turkish Policy Quarterly (TPQ) Design/Production: Osman Balaban Printed by Moda Ofset Basım Yayın San.Tic.Ltd.Şti. Istanbul, Turkey All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be copied, redistributed, or published without express permission in writing from the publisher. The views reflected here are purely personal and do not represent the views of CI, SAM, or TPQ. CONTENTS Conference Organizers and Panelists 4 Introduction 6 Opening Remarks 7 Key Debates 1. Change and Continuity of Independence 8 2. Astronomic Expectations vs. Earthly Realities 10 3. South Caucasus: a malfunctioning region? 12 4. Small States and Big Neighbors – The Question of Alignments 15 5. Boundaries and Barriers: Relations with Neighbors 19 Summary: Highlights from the Speakers 27 Post-Conference Evaluation Report Conference Organizers and Panellists Center for Strategic Studies (SAM) The Center for Strategic Studies (www.sam.gov.az) is Azer- baijan’s first government-funded, non-profit and academically independent think tank, known as SAM (Strateji Araşdırmalar Mərkəzi in Azerbaijani). The mission of SAM is to promote collaborative research and enhance the strategic debate as well as providing decision-makers with high-quality analysis and innovative proposals for action. Through publications, brain- storming meetings, conferences and policy recommendations, SAM conducts rigorous research guided by a forward-looking policy orientation, thus bringing new perspectives to strategic discussions and contributing to informed decision making in Azerbaijan Turkish Policy Quarterly (TPQ) Turkish Policy Quarterly (www.turkishpolicy.com) is an Istan- bul-based journal published on a quarterly basis since 2002. -

Forced Displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh Conflict: Return and Its Alternatives

Forced displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict: return and its alternatives August 2011 conciliation resources Place-names in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict are contested. Place-names within Nagorny Karabakh itself have been contested throughout the conflict. Place-names in the adjacent occupied territories have become increasingly contested over time in some, but not all (and not official), Armenian sources. Contributors have used their preferred terms without editorial restrictions. Variant spellings of the same name (e.g., Nagorny Karabakh vs Nagorno-Karabakh, Sumgait vs Sumqayit) have also been used in this publication according to authors’ preferences. Terminology used in the contributors’ biographies reflects their choices, not those of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. For the map at the end of the publication, Conciliation Resources has used the place-names current in 1988; where appropriate, alternative names are given in brackets in the text at first usage. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. Altered street sign in Shusha (known as Shushi to Armenians). Source: bbcrussian.com Contents Executive summary and introduction to the Karabakh Contact Group 5 The Contact Group papers 1 Return and its alternatives: international law, norms and practices, and dilemmas of ethnocratic power, implementation, justice and development 7 Gerard Toal 2 Return and its alternatives: perspectives -

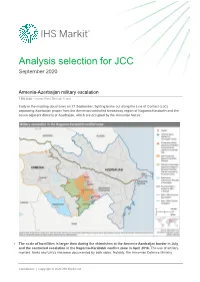

Analysis Selection for JCC September 2020

Analysis selection for JCC September 2020 Armenia-Azerbaijan military escalation 1 Oct 2020 - Country Risk | Strategic Report Early in the morning (local time) on 27 September, fighting broke out along the Line of Contact (LoC) separating Azerbaijan proper from the Armenian-controlled breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh and the seven adjacent districts of Azerbaijan, which are occupied by the Armenian forces. • The scale of hostilities is larger than during the skirmishes at the Armenia-Azerbaijan border in July and the controlled escalation in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict zone in April 2016. The use of artillery, mortars, tanks and UAVs has been documented by both sides. Notably, the Armenian Defence Ministry Confidential | Copyright © 2020 IHS Markit Ltd Analysis selection for JCC - September 2020 claims that the Azeri armed forces employed Soviet-era Smerch, Turkish Kasirga and Belarusian Polonez multiple rocket launch systems, which indicate a significant escalation and the indiscriminatory nature of the assault. On 30 September, the Armenian authorities stated that on 29 September, a Turkish F-16 fighter jet allegedly shot down an Armenian Su-25 aircraft in the Armenian airspace above Gegharkunik province. This information was accompanied by the release of the photo evidence showing the wreckage of the plane and the identity of the pilot, Armenian Air Force Major Valeriy Danilin. If true, this would represent a significant further escalation, indicating spillover of combat into Armenia proper. However, both Azerbaijan and Turkey denied these allegations while, as of 1 October 2020, the Armenian side has yet to produce more evidence, including fragments of air-to-air missile (AIM-120 AMRAAM) that purportedly downed the Armenian aircraft. -

Armenia and Azerbaijan–2008-2012

: Armenia and Azerbaijan–2008-2012 Disclaimer Contact the Geospatial Technologies Project geotech © Copyright 2015 Geospatial Technologies Project Program Associate Acknowledgement ! Introduction* * Nagorno)Karabakh!is!a!mountainous!region!in!the!South!Caucasus!situated!roughly!100! kilometers!southeast!of!the!Armenian!capital,!Yerevan.!Although!inhabited!largely!by!ethnic! Armenians,!during!the!Soviet!period!the!region!was!an!administrative!division!of!the!Azerbaijan! Soviet!Socialist!Republic!known!as!the!Nagorno)Karabakh!Autonomous!Oblast!(NKAO).!For!most! of!that!era,!however,!the!long)standing!ethnic!tensions!that!existed!between!Armenians!and! Azeris!in!the!region!were!effectively!suppressed!by!the!Soviet!authorities.!With!the!arrival!of! Glasnost!in!the!late!1980s,!this!situation!changed,!and!public!demonstrations!both!for!and! against!the!Oblast’s!cession!to!Armenia!occurred!frequently.1! ! In!early!1988,!in!the!town!of!Askeran,!these!events!turned!violent,!when!confrontations! between!the!Armenian!population!and!a!crowd!of!Azeris!from!nearby!Agdam!ended!with!two! Azeris!killed!under!unclear!circumstances.!This!clash!was!followed!by!a!severe!pogrom!against! ethnic!Armenians!living!in!Sumgait,!a!suburb!of!the!Azerbaijani!capital!of!Baku.!In!Armenia,! outrage!over!the!events!in!Sumgait!combined!with!frustration!over!Moscow’s!decision!on!23! March!not!to!award!Nagorno)Karabakh!to!Armenia,!and!led!to!the!massive!expulsion!of!Azeris! living!in!Armenian!territory,!including!the!burning!of!nine!villages.!In!Azerbaijan,!fearing! -

Assessment of Pollution of the Atmospheric Air in the Cities of Azerbaijan

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 18; October 2013 Assessment of Pollution of the Atmospheric Air in the Cities of Azerbaijan Shakar Mammadova Baku State University Baku city, Az1073/1, Azerbaijan. Abstract The article is devoted to the results of monitoring of the pollution of the atmospheric air by 26 observation points based in 8 large industrial cities of Azerbaijan. The observations were carried out by 18 harmful substances, including dust, sulfur dioxide, soluble sulfates, carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxide (IV), nitric oxide (II), hydrogen sulfide, soot, solid fluorides, hydrogen fluoride, mercury, ammonia, sulfuric acid, formaldehyde, phenols, furfuralin the atmospheric air. On the basis of the monitoring, concentrations of these substances are being defined. Key words: ingredient, pollutant, concentration, substances, precipitation Introduction The observations on the pollution of the atmospheric air were made by the observation points based in eight largest cities of the Republic of Azerbaijan, including Baku, Sumgait, Ganja, Mingachevir, Nakhchivan, Sheki, and Shirvan, and Lankaran.At observation points, the overall number of which is 26, 102796 analyses have been implemented by 100434 samples during ayear. The amount of dust, sulfur dioxide, soluble sulfates, carbon dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, nitric oxide, hydrogen sulfide, soot, solid fluorides, hydrogen fluoride, mercury, ammonia, sulfuric acid, formaldehyde, phenols and furfural per unit volume have been defined with different ways. The results allow identify the definite concentrations of the harmful substances in the atmospheric air of cities. Determination of the amount of dust in the air is based on the definition of mass of dust particles absorbed by special filter. Dust concentration is determined by the weight method. -

Time for Armenian and Azerbaijani Diasporas to Talk to Each Other

Time for Armenian and Azerbaijani diasporas to talk to each other https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article6936 Nagorno-Karabakh Time for Armenian and Azerbaijani diasporas to talk to each other - IV Online magazine - 2020 - IV551 - December 2020 - Publication date: Tuesday 8 December 2020 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/4 Time for Armenian and Azerbaijani diasporas to talk to each other The 2018 changes in Armenia did not produce any revolutionary discourse concerning the Karabakh conflict. In Yerevan as in Baku, political elites do not seem able to imagine how to resolve this conflict. I call Diaspora Armenians and Azerbaijanis living abroad to make a bold initiative and start a new dialogue, may be they could move a process that is central in determining the future of their homelands, yet remains paralyzed for nearly two decades. It was 20 years ago, in June 1999, when I went to Baku with a group of journalists from Armenia, Karabakh, and Georgia. It was part of a project I had initiated in 1997 where I wanted to offer journalists in the South Caucasus a chance to see "to the other side" of the conflict line, to meet and exchange with colleagues and politicians of their neighbouring countries. Weren't they members of the same Soviet Union, I thought? By knowing the concerns, fears and hopes of the other, journalists could propose a more nuanced reporting, and therefore influence the public opinion towards mutual understanding and eventually contributed to conflict resolution. Our visit to Baku was the result of efforts of several years. -

Administrative Territorial Divisions in Different Historical Periods

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y TERRITORIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS C O N T E N T I. GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................. 3 II. BAKU ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. General background of Baku ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. History of the city of Baku ................................................................................................................................. 7 3. Museums ........................................................................................................................................................... 16 4. Historical Monuments ...................................................................................................................................... 20 The Maiden Tower ............................................................................................................................................ 20 The Shirvanshahs’ Palace ensemble ................................................................................................................ 22 The Sabael Castle .............................................................................................................................................