Ethnic Fears and Ethnic War in Karabagh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

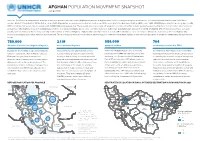

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

Asala & ARF 'Veterans' in Armenia and the Nagorno-Karabakh Region

Karabakh Christopher GUNN Coastal Carolina University ASALA & ARF ‘VETERANS’ IN ARMENIA AND THE NAGORNO-KARABAKH REGION OF AZERBAIJAN Conclusion. See the beginning in IRS- Heritage, 3 (35) 2018 Emblem of ASALA y 1990, Armenia or Nagorno-Karabakh were, arguably, the only two places in the world that Bformer ASALA terrorists could safely go, and not fear pursuit, in one form or another, and it seems that most of them did, indeed, eventually end up in Armenia (36). Not all of the ASALA veterans took up arms, how- ever. Some like, Alex Yenikomshian, former director of the Monte Melkonian Fund and the current Sardarapat Movement leader, who was permanently blinded in October 1980 when a bomb he was preparing explod- ed prematurely in his hotel room, were not capable of actually participating in the fighting (37). Others, like Varoujan Garabedian, the terrorist behind the attack on the Orly Airport in Paris in 1983, who emigrated to Armenia when he was pardoned by the French govern- ment in April 2001 and released from prison, arrived too late (38). Based on the documents and material avail- able today in English, there were at least eight ASALA 48 www.irs-az.com 4(36), AUTUMN 2018 Poster of the Armenian Legion in the troops of fascist Germany and photograph of Garegin Nzhdeh – terrorist and founder of Tseghakronism veterans who can be identified who were actively en- tia group of approximately 50 men, and played a major gaged in the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh (39), but role in the assault and occupation of the Kelbajar region undoubtedly there were more. -

THE IMPACT of the ARMENIAN GENOCIDE on the FORMATION of NATIONAL STATEHOOD and POLITICAL IDENTITY “Today Most Armenians Do

ASHOT ALEKSANYAN THE IMPACT OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE ON THE FORMATION OF NATIONAL STATEHOOD AND POLITICAL IDENTITY Key words – Armenian Genocide, pre-genocide, post-genocide, national statehood, Armenian statehood heritage, political identity, civiliarchic elite, civilization, civic culture, Armenian diaspora, Armenian civiliarchy “Today most Armenians do not live in the Republic of Armenia. Indeed, most Armenians have deep ties to the countries where they live. Like a lot of us, many Armenians find themselves balancing their role in their new country with their historical and cultural roots. How far should they assimilate into their new countries? Does Armenian history and culture have something to offer Armenians as they live their lives now? When do historical and cultural memories create self-imposed limits on individuals?”1 Introduction The relevance of this article is determined, on the one hand, the multidimen- sionality of issues related to understanding the role of statehood and the political and legal system in the development of Armenian civilization, civic culture and identity, on the other hand - the negative impact of the long absence of national system of public administration and the devastating impact of the Armenian Genocide of 1915 on the further development of the Armenian statehood and civiliarchy. Armenian Genocide in Ottoman Turkey was the first ever large-scale crime against humanity and human values. Taking advantage of the beginning of World War I, the Turkish authorities have organized mass murder and deportations of Armenians from their historic homeland. Genocide divided the civiliarchy of the Armenian people in three parts: before the genocide (pre-genocide), during the genocide and after the genocide (post-genocide). -

Oct. 6-12, 2020 Further Reproduction Or Distribution Is Subject to Original Copyright Restrictions

Weekly Media Report –Oct. 6-12, 2020 Further reproduction or distribution is subject to original copyright restrictions. ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…… EDUCATION: 1. Marine Corps’ Landmark PhD Program Celebrates First Technical Graduate (Marines.mil 7 Oct 20) (Navy.mil 7 Oct 20) (NPS.edu 7 Oct 20) (Military Spot 12 Oct 20) … Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Taylor Vencill When the Marine Corps developed its new Doctor of Philosophy Program (PHDP), the service recognized the need for a cohort of strategic thinkers and technical leaders capable of the applied research and innovative thinking necessary to develop warfighter advantage in the modern, cognitive age. The Technical version of the program, PHDP-T, just celebrated its first graduate, with Maj. Ezra Akin completing his doctorate in operations research from the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS), Sept. 25. INDUSTRY PARTNERS: 2. Denver Startup Kayhan Space Lands $600k Seed Round for Collision Avoidance Software (ColoradoInno 6 Oct 20) … Nick Greenhalgh Much like on city streets, space traffic can be hectic and near misses are becoming all too common. Just last year, an in-orbit European Space Agency satellite was forced to perform an evasive maneuver to avoid a collision with a SpaceX satellite. Kayhan Space currently provides satellite collision assessment and avoidance support to the Naval Postgraduate School and BlackSky missions. FACULTY: 3. Will Armenia and Azerbaijan Fight to the Bitter End? [AUDIO INTERVIEW] (English News Highlights 5 Oct 20) Armenia and Azerbaijan accuse each other of attacking civilian areas as the deadliest fighting in the South Caucasus region for more than 25 years continues. KAN's Mark Weiss spoke with South Caucasus expert Brenda Shaffer, formerly a professor at Haifa University and now at the US Navy Postgraduate University. -

May 22, 1947 Memorandum, Armenian Communist Party Central

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified May 22, 1947 Memorandum, Armenian Communist Party Central Committee Secretary Grigory Arutinov to Josef Stalin, 'About the Mood of a Part of the Armenians Repatriated From Foreign Countries' Citation: “Memorandum, Armenian Communist Party Central Committee Secretary Grigory Arutinov to Josef Stalin, 'About the Mood of a Part of the Armenians Repatriated From Foreign Countries',” May 22, 1947, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, National Armenian Archives. Translated by Svetlana Savranskaya http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/117338 Summary: Arutinov reports on the mood of the "repatriated" Armenians, members of the diaspora who were encouraged to move to Armenia by the Soviet government. The report describes assistance given to the over 50,000 repatriated Armenians and efforts to deal with dissatisfied members who were "in favor of re-emigration." Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation SECRETARY CC VCP/b/ Comrade STALIN I. V. ABOUT THE MOOD OF A PART OF THE ARMENIANS REPATRIATED FROM FOREIGN COUNTRIES Out of 50,945 Armenians, who arrived from foreign countries, 20,900 are able to work; they all were given employment at industrial enterprises, construction, in the teams of craft cooperation, and the peasants— in the collective and state farms. The main mass of repatriated Armenians adjusted to their jobs and takes an active part in productive activities. A significant part participates in the socialist competition—for early fulfillment of the plans, and many of those exhibit high standards in their work. There is a small part of the repatriated, who initially switched from one job to another and subsequently engaged in trade and speculation on the markets. -

3. Energy Reserves, Pipeline Routes and the Legal Regime in the Caspian Sea

3. Energy reserves, pipeline routes and the legal regime in the Caspian Sea John Roberts I. The energy reserves and production potential of the Caspian The issue of Caspian energy development has been dominated by four factors. The first is uncertain oil prices. These pose a challenge both to oilfield devel- opers and to the promoters of pipelines. The boom prices of 2000, coupled with supply shortages within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), have made development of the resources of the Caspian area very attractive. By contrast, when oil prices hovered around the $10 per barrel level in late 1998 and early 1999, the price downturn threatened not only the viability of some of the more grandiose pipeline projects to carry Caspian oil to the outside world, but also the economics of basic oilfield exploration in the region. While there will be some fly-by-night operators who endeavour to secure swift returns in an era of high prices, the major energy developers, as well as the majority of smaller investors, will continue to predicate total production costs (including carriage to market) not exceeding $10–12 a barrel. The second is the geology and geography of the area. The importance of its geology was highlighted when two of the first four international consortia formed to look for oil in blocks off Azerbaijan where no wells had previously been drilled pulled out in the wake of poor results.1 The geography of the area involves the complex problem of export pipeline development and the chicken- and-egg question whether lack of pipelines is holding back oil and gas pro- duction or vice versa. -

The Effects of Nationalism on Territorial Integrity Among Armenians and Serbs Nina Patelic

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 The Effects of Nationalism on Territorial Integrity Among Armenians and Serbs Nina Patelic Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE EFFECTS OF NATIONALISM ON TERRITORIAL INTEGRITY AMONG ARMENIANS AND SERBS By Nina Patelic A Thesis submitted to the Department of International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Nina Pantelic, defended on September 28th, 2007. ------------------------------- Jonathan Grant Professor Directing Thesis ------------------------------- Peter Garretson Committee Member ------------------------------- Mark Souva Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKOWLEDGEMENTS This paper could not have been written without the academic insight of my thesis committee members, as well as Dr. Kotchikian. I would also like to thank my parents Dr. Svetlana Adamovic and Dr. Predrag Pantelic, my grandfather Dr. Ljubisa Adamovic, my sister Ana Pantelic, and my best friend, Jason Wiggins, who have all supported me over the years. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………..v INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………….1 1. NATIONALISM, AND HOW IT DEVELOPED IN SERBIA AND ARMENIA...6 2. THE CONFLICT OVER KOSOVO AND METOHIJA…………………………...27 3. THE CONFLICT OVER NAGORNO KARABAKH……………………………..56 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………...……….89 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………93 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH………………………………………………………….101 iv ABSTRACT Nationalism has been a driving force in both nation building and in spurring high levels of violence. As nations have become the norm in modern day society, nationalism has become detrimental to international law, which protects the powers of sovereignty. -

1411972* A/Hrc/25/G/14

联 合 国 A/HRC/25/G/14 大 会 Distr.: General 11 March 2014 Chinese Original: English 人权理事会 第二十五届会议 议程项目 4 需要理事会注意的人权状况 阿塞拜疆共和国常驻联合国日内瓦办事处代表 2014 年 2 月 24 日致人权理事会主席的信 我谨随函转交阿塞拜疆共和国常驻代表团关于阿塞拜疆霍贾利种族灭绝事 件二十二周年纪念活动的新闻稿。 谨请将本函及其附件* 作为人权理事会第二十五届会议议程项目 4 下的文件 分发。 大使、常驻代表 Murad N. Najafbayli (签名) * 附件不译,原文照发。 GE.14-11972 (C) 140314 180314 *1411972* A/HRC/25/G/14 Annex [English only] Commemoration of the twenty-second anniversary of the Khojaly Genocide The most serious crimes of concern to the international community, such as war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, have been committed in the course of the ongoing aggression of the Republic of Armenia against the Republic of Azerbaijan. In the upcoming days, Azerbaijan commemorates the twenty-second anniversary of the atrocious crimes committed against the civilians and defenders of the town of Khojaly, situated in the Nagorno Karabakh region of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Late into the night of February 25, 1992 the town of Khojaly has become under the intensive fire from the town of Khankendi and Askeran that already occupied by Armenian forces. At night from February 25 to 26 the Armenian armed forces supported by the ex- Soviet 366th regiment completed the surrounding of the town already isolated due to ethnic cleansing of Azerbaijani population of its neighboring regions. The joint forces have occupied the town which has been brought in rubbishes by heavy artillery shelling. After all 150 people defending the town were killed by overwhelmed fire and by superior forces of advancing army regiments the remaining handful of the town’s defendants provided a humanitarian corridor for several hundreds of the town’s residents to escape from their homes. -

The Armenian Genocide

The Armenian Genocide During World War I, the Ottoman Empire carried out what most international experts and historians have concluded was one of the largest genocides in the world's history, slaughtering huge portions of its minority Armenian population. In all, over 1 million Armenians were put to death. To this day, Turkey denies the genocidal intent of these mass murders. My sense is that Armenians are suffering from what I would call incomplete mourning, and they can't complete that mourning process until their tragedy, their wounds are recognized by the descendants of the people who perpetrated it. People want to know what really happened. We are fed up with all these stories-- denial stories, and propaganda, and so on. Really the new generation want to know what happened 1915. How is it possible for a massacre of such epic proportions to take place? Why did it happen? And why has it remained one of the greatest untold stories of the 20th century? This film is made possible by contributions from John and Judy Bedrosian, the Avenessians Family Foundation, the Lincy Foundation, the Manoogian Simone Foundation, and the following. And others. A complete list is available from PBS. The Armenians. There are between six and seven million alive today, and less than half live in the Republic of Armenia, a small country south of Georgia and north of Iran. The rest live around the world in countries such as the US, Russia, France, Lebanon, and Syria. They're an ancient people who originally came from Anatolia some 2,500 years ago. -

Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on Its Fundamentals

International Journal of Philosophy and Theology September 2014, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 93-106 ISSN: 2333-5750 (Print), 2333-5769 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on its Fundamentals Parisa Ghorbannejad1 Abstract Islamic Sufism started in Azerbaijan later than other Islamic regions for some reasons.Early Sufis in this region had been inspired by mysterious beliefs of Zarathustra which played an important role in future path of Sufism in Iran the consequences of which can be seen in illumination theory. This research deals with the reason of the delay in the advent of Sufism in Azerbaijan compared with other regions in a descriptive analytic method. Studies show that the deficiency of conqueror Arabs, loyalty of ethnic people to Iranian religion and the influence of theosophical beliefs such as heart's eye, meeting the right, relation between body and soul and cross evidences in heart had important effects on ideas and thoughts of Azerbaijan's first Sufis such as Ebn-e-Yazdanyar. Investigating Arab victories and conducting case studies on early Sufis' thoughts and ideas, the author attains considerable results via this research. Keywords: Sufism, Azerbaijan, Zarathustra, Ebn-e-Yazdanyar, Islam Introduction Azerbaijan territory2 with its unique geography and history, was the cultural center of Iran for many years in Sasanian era and was very important for Zarathustra religion and Magi class. 1 PhD, Faculty of Science, Islamic Azad University, Urmia Branch,WestAzarbayjan, Iran. -

"From Ter-Petrosian to Kocharian: Leadership Change in Armenia

UC Berkeley Recent Work Title From Ter-Petrosian to Kocharian: Leadership Change in Armenia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0c2794v4 Author Astourian, Stephan H. Publication Date 2000 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California University of California, Berkeley FROM TER-PETROSIAN TO KOCHARIAN: LEADERSHIP CHANGE IN ARMENIA Stephan H. Astourian Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Working Paper Series This PDF document preserves the page numbering of the printed version for accuracy of citation. When viewed with Acrobat Reader, the printed page numbers will not correspond with the electronic numbering. The Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies (BPS) is a leading center for graduate training on the Soviet Union and its successor states in the United States. Founded in 1983 as part of a nationwide effort to reinvigorate the field, BPSs mission has been to train a new cohort of scholars and professionals in both cross-disciplinary social science methodology and theory as well as the history, languages, and cultures of the former Soviet Union; to carry out an innovative program of scholarly research and publication on the Soviet Union and its successor states; and to undertake an active public outreach program for the local community, other national and international academic centers, and the U.S. and other governments. Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies University of California, Berkeley Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies 260 Stephens Hall #2304 Berkeley, California 94720-2304 Tel: (510) 643-6737 [email protected] http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~bsp/ FROM TER-PETROSIAN TO KOCHARIAN: LEADERSHIP CHANGE IN ARMENIA Stephan H. -

The Caucasus Globalization

Volume 8 Issue 3-4 2014 1 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies Volume 8 Issue 3-4 2014 CA&CC Press® SWEDEN 2 Volume 8 Issue 3-4 2014 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION FOUNDED AND PUBLISHED BY INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS Registration number: M-770 Ministry of Justice of Azerbaijan Republic PUBLISHING HOUSE CA&CC Press® Sweden Registration number: 556699-5964 Registration number of the journal: 1218 Editorial Council Eldar Chairman of the Editorial Council (Baku) ISMAILOV Tel/fax: (994 – 12) 497 12 22 E-mail: [email protected] Kenan Executive Secretary (Baku) ALLAHVERDIEV Tel: (994 – 12) 561 70 54 E-mail: [email protected] Azer represents the journal in Russia (Moscow) SAFAROV Tel: (7 – 495) 937 77 27 E-mail: [email protected] Nodar represents the journal in Georgia (Tbilisi) KHADURI Tel: (995 – 32) 99 59 67 E-mail: [email protected] Ayca represents the journal in Turkey (Ankara) ERGUN Tel: (+90 – 312) 210 59 96 E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Board Nazim Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) MUZAFFARLI Tel: (994 – 12) 598 27 53 (Ext. 25) (IMANOV) E-mail: [email protected] Vladimer Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Georgia) PAPAVA Tel: (995 – 32) 24 35 55 E-mail: [email protected] Akif Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) ABDULLAEV Tel: (994 – 12) 561 70 54 E-mail: [email protected] Volume 8 IssueMembers 3-4 2014 of Editorial Board: 3 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Zaza D.Sc. (History), Professor, Corresponding member of the Georgian National Academy of ALEKSIDZE Sciences, head of the scientific department of the Korneli Kekelidze Institute of Manuscripts (Georgia) Mustafa AYDIN Rector of Kadir Has University (Turkey) Irina BABICH D.Sc.