Geography of Early Historical Punjab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peon Fatehgarh.Pdf

Department of Local Government Punjab (Punjab Municipal Bhawan, Plot No.-3, Sector-35 A, Chandigarh) Detail of application for the posts of Peon (Service Group-D) reserved for Disabled Persons in the cadre of Municipal Corporations and Municipal Councils-Nagar Panchayats in Punjab Sr. App Name of Candidate Address Date of Birth VH, HH, OH No. No. and Father’s Name etc. %age of Sarv Shri/ Smt./ disability Miss 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 191 Narinder Singh S/o Village Atta Pur, P.O. 26.03.1986 OH 45% Shambu Ram Charnarthal Kalan, Fatehgarh Sahib. 2 192 Gurjant Singh S/o Village Nariana, P.O. 20.05.1983 OH 60% Avtar Singh Bhagrana, Teh Bassi Pathana, Distt. Fatehgarh Sahib. 3 386 Gurwinder Singh S/o V.P.O Hallal Pur, Teh. 01.01.1991 OH 70% Sukhvinder Singh and Distt. Fatehgarh Sahib 4 411 Lakhwinder Singh Vill. Fateh Pur Araian, 04.02.1992 OH 85% S/o Meva Singh Teh. Basi Bathana, Distt.- Fateh Garh Sahib PB- 140412 5 501 Satpal Singh S/o V.P.O Malko Majra, Distt. 17.02.1981 OH 50% Hari Singh Fatehgarh Sahib 6 563 Balwant Singh S/o Village Dedrha, PO 20.12.1992 OH 70% Bahadur Singh Kumbadgarh, Fatehgarh Sahib 7 665 Narinder Singh S/o Vill. Dadiana, Teh. Bassi 05.10.1986 OH 100% Shamsher Singh Pathana, PO Rupalheri, District Fathegarh Sahib. 8 752 Tejvir Singh S/o W.No: 12, Amloh, Distt: 03.07.1990 OH 40% Chhajju Ram Fatehgarh Sahib. 9 885 Jagjit Singh S/o Vill. -

List of Sewa Kendras Retained

List 2 - List of Sewa Kendras Retained List 2 - List of Sewa Kendras Retained S No District Sewa Kendra Name and Location Center Code Type 1 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, HO, Kitchlu Chownk PB-049-00255-U025 Type-I 2 Amritsar MC Majitha Near Telephone Exchange PB-049-00255-U001 Type-II 3 Amritsar MC Jandiala Near Bus Stand PB-049-00255-U002 Type-II 4 Amritsar Chamrang Road (Park) PB-049-00255-U004 Type-II 5 Amritsar Gurnam Nagar/Sakatri Bagh PB-049-00255-U008 Type-II 6 Amritsar Lahori Gate PB-049-00255-U011 Type-II 7 Amritsar Kot Moti Ram PB-049-00255-U015 Type-II 8 Amritsar Zone No 6 - Basant Park, Basant Avenue PB-049-00255-U017 Type-II Zone No 7 - PWD (B&R) Office Opp. 9 Amritsar PB-049-00255-U019 Type-II Celebration Mall 10 Amritsar Zone No 8- Japani Mill (Park), Chherata PB-049-00255-U023 Type-II Suwidha Centre, DTO Office, Ram Tirath 11 Amritsar PB-049-00255-U026 Type-II Road, Asr 12 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, Ajnala PB-049-00255-U028 Type-II Suwidha Centre, Batala Road, Baba 13 Amritsar PB-049-00255-U029 Type-II Bakala Sahib 14 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, Attari PB-049-00255-U031 Type-II 15 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, Lopoke PB-049-00255-U032 Type-II 16 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, Tarsikka PB-049-00255-U034 Type-II 17 Amritsar Ajnala PB-049-00255-R001 Type-II 18 Amritsar Ramdass PB-049-00255-R002 Type-III 19 Amritsar Rajasansi PB-049-00259-R003 Type-II 20 Amritsar Market Committee Rayya Office PB-049-00259-R005 Type-II 21 Amritsar Jhander PB-049-00255-R025 Type-III 22 Amritsar Chogawan PB-049-00255-R027 Type-III 23 Amritsar Jasrur PB-049-00255-R035 -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Of Dr. R.S. Bisht Joint Director General (Retd.) Archaeological Survey of India & Padma Shri Awardee, 2013 Address: 9/19, Sector-3, Rajendranagar, Sahibabad, Ghaziabad – 201005 (U.P.) Tel: 0120-3260196; Mob: 09990076074 Email: [email protected] i Contents Pages 1. Personal Data 1-2 2. Excavations & Research 3-4 3. Conservation of Monuments 5 4. Museum Activities 6-7 5. Teaching & Training 8 6. Research Publications 9-12 7. A Few Important Research papers presented 13-14 at Seminars and Conferences 8. Prestigious Lectures and Addresses 15-19 9. Memorial Lectures 20 10. Foreign Countries and Places Visited 21-22 11. Members on Academic and other Committees 23-24 12. Setting up of the Sarasvati Heritage Project 25 13. Awards received 26-28 ii CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Personal Data Name : DR. RAVINDRA SINGH BISHT Father's Name : Lt. Shri L. S. Bisht Date of Birth : 2nd January 1944 Nationality : Indian by birth Permanent Address : 9/19, Sector-3, Rajendranagar, Sahibabad Ghaziabad – 201 005 (U.P.) Academic Qualifications Degree Subject University/ Institution Year M.A . Ancient Indian History and Lucknow University, 1965. Culture, PGDA , Prehistory, Protohistory, School of Archaeology 1967 Historical archaeology, Conservation (Archl. Survey of India) of Monuments, Chemical cleaning & preservation, Museum methods, Antiquarian laws, Survey, Photography & Drawing Ph. D. Emerging Perspectives of Kumaun University 2002. the Harappan Civilization in the Light of Recent Excavations at Banawali and Dholavira Visharad Hindi Litt., Sanskrit, : Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, Prayag 1958 Sahityaratna, Hindi Litt. -do- 1960 1 Professional Experience 35 years’ experience in Archaeological Research, Conservation & Environmental Development of National Monuments and Administration, etc. -

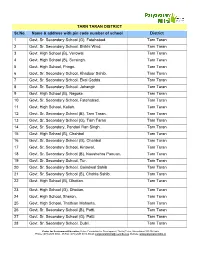

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

Physical Geography of the Punjab

19 Gosal: Physical Geography of Punjab Physical Geography of the Punjab G. S. Gosal Formerly Professor of Geography, Punjab University, Chandigarh ________________________________________________________________ Located in the northwestern part of the Indian sub-continent, the Punjab served as a bridge between the east, the middle east, and central Asia assigning it considerable regional importance. The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the rivers - Satluj, Beas, Ravi, Chanab and Jhelam. The paper provides a detailed description of Punjab’s physical landscape and its general climatic conditions which created its history and culture and made it the bread basket of the subcontinent. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Herodotus, an ancient Greek scholar, who lived from 484 BCE to 425 BCE, was often referred to as the ‘father of history’, the ‘father of ethnography’, and a great scholar of geography of his time. Some 2500 years ago he made a classic statement: ‘All history should be studied geographically, and all geography historically’. In this statement Herodotus was essentially emphasizing the inseparability of time and space, and a close relationship between history and geography. After all, historical events do not take place in the air, their base is always the earth. For a proper understanding of history, therefore, the base, that is the earth, must be known closely. The physical earth and the man living on it in their full, multi-dimensional relationships constitute the reality of the earth. There is no doubt that human ingenuity, innovations, technological capabilities, and aspirations are very potent factors in shaping and reshaping places and regions, as also in giving rise to new events, but the physical environmental base has its own role to play. -

The First Occurrence of Eurygnathohippus Van Hoepen, 1930 (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Equidae) Outside Africa and Its Biogeograph

TO L O N O G E I L C A A P I ' T A A T L E I I A Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana, 58 (2), 2019, 171-179. Modena C N O A S S. P. I. The frst occurrence of Eurygnathohippus Van Hoepen, 1930 (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Equidae) outside Africa and its biogeographic signifcance Advait Mahesh Jukar, Boyang Sun, Avinash C. Nanda & Raymond L. Bernor A.M. Jukar, Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20013, USA; [email protected] B. Sun, Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China; University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100039, China; College of Medicine, Department of Anatomy, Laboratory of Evolutionary Biology, Howard University, Washington D.C. 20059, USA; [email protected] A.C. Nanda, Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, Dehra Dun 248001, India; [email protected] R.L. Bernor, College of Medicine, Department of Anatomy, Laboratory of Evolutionary Biology, Howard University, Washington D.C. 20059, USA; [email protected] KEY WORDS - South Asia, Pliocene, Biogeography, Dispersal, Siwalik, Hipparionine horses. ABSTRACT - The Pliocene fossil record of hipparionine horses in the Indian Subcontinent is poorly known. Historically, only one species, “Hippotherium” antelopinum Falconer & Cautley, 1849, was described from the Upper Siwaliks. Here, we present the frst evidence of Eurygnathohippus Van Hoepen, 1930, a lineage hitherto only known from Africa, in the Upper Siwaliks during the late Pliocene. Morphologically, the South Asian Eurygnathohippus is most similar to Eurygnathohippus hasumense (Eisenmann, 1983) from Afar, Ethiopia, a species with a similar temporal range. -

Museum Brochure

CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF PUNJAB MUSEUM AN INTRODUCTION Subhash Parihar Central University of Punjab Mansa Road, Bathinda-151001. The Malwa region of Punjab—the plains lying between the rivers Sutlej and the Ghaggar—has a long and rich history. On the basis of archaeological excavations, the history of the region can be traced back to the Harappan period, i.e., more than four millenniums. But these traces of its history are fast falling prey to the unplanned development and avarice of the greedy people for land. Although life styles have always been in a flux, the speed of change has accelerated during recent times. Old life styles are vanishing faster and faster. The artefacts, tools, vessels, people used a few decades back are rarely seen now. Although the change cannot be halted, a record of these life styles and specimens of objects must be preserved for future generations. Keeping in view the significance of preserving the material remains of the past, Prof. (Dr.) Jai Rup Singh, the Vice-Chancellor of the Central University of Punjab decided to establish a museum in the university to preserve the rich history and culture of the region. The main purpose of this museum is to ‘acquire, conserve, research, communicate and exhibit, for purposes of study, education and enjoyment, material evidence of people and their environment.’ The CUPB Museum is housed in the Hall No. 1 of the Academic Block of the university, measuring 91 X 73.25 feet, covering a floor area of about 6600 square feet. The collection is organized in a number of sections, each dealing with a specific theme. -

The Stūpa of Bharhut

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GIFT OF Alexander B. Griswold FINE ARTS Cornell Univ.;rsily Library NA6008.B5C97 The stupa of Bharhut:a Buddhist monumen 3 1924 016 181 111 ivA Cornell University Library Al The original of this bool< is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 92401 6181111 ; THE STUPA OF BHARHUT: A BUDDHIST MONUMENT ORNAMENTED WITH NUMEROUS SCULPTURES ILLUSTRATIVE OF BTJDDHIST LEGEND AND HISTOEY IN THE THIRD CENTURY B.C. BY ALEXANDER CUNNINGHAM, C.S.I., CLE., ' ' ' ^ MAJOE GENERAL, EOYAL ENGINEERS (BENGAL, RETIRED). DIRECTOR GENERAL ARCHffiOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA. " In the sculptures ancL insorvptions of Bharliut we shall have in future a real landmarh in the religious and literary history of India, and many theories hitherto held hy Sanskrit scholars will have to he modified accordingly."— Dr. Max Mullee. UlM(h hu Mw af i\( Mx(hx^ tii ^tate Ux %nVm in €mml LONDON: W^ H. ALLEN AND CO., 13, WATERLOO PLACE, S.W. TRUBNER AND CO., 57 & 59, LUDGATE HILL; EDWARD STANFORD, CHARING CROSS; W. S. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., 91, GRACECHURCH STREET; THACKER AND CO., 87, NEWGATE STREET. 1879. CONTENTS. page E.—SCULPTURED SCENES. PAGE PREFACE V 1. Jata^as, oe pebvious Bieths of Buddha - 48 2. HisTOEicAL Scenes - - - 82 3. Miscellaneous Scenes, insceibed - 93 I.—DESCRIPTION OF STUPA. 4. Miscellaneous Scenes, not insceibed - 98 1. Position of Bhakhut 1 5. HuMOEOUS Scenes - - - 104 2. Desckipiion of Stupa 4 F.— OF WORSHIP 3. Peobable Age of Stupa - 14 OBJECTS 1. -

Custom, Law and John Company in Kumaon

Custom, law and John Company in Kumaon. The meeting of local custom with the emergent formal governmental practices of the British East India Company in the Himalayan region of Kumaon, 1815–1843. Mark Gordon Jones, November 2018. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University. © Copyright by Mark G. Jones, 2018. All Rights Reserved. This thesis is an original work entirely written by the author. It has a word count of 89,374 with title, abstract, acknowledgements, footnotes, tables, glossary, bibliography and appendices excluded. Mark Jones The text of this thesis is set in Garamond 13 and uses the spelling system of the Oxford English Dictionary, January 2018 Update found at www.oed.com. Anglo-Indian and Kumaoni words not found in the OED or where the common spelling in Kumaon is at a great distance from that of the OED are italicized. To assist the reader, a glossary of many of these words including some found in the OED is provided following the main thesis text. References are set in Garamond 10 in a format compliant with the Chicago Manual of Style 16 notes and bibliography system found at http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org ii Acknowledgements Many people and institutions have contributed to the research and skills development embodied in this thesis. The first of these that I would like to acknowledge is the Chair of my supervisory panel Dr Meera Ashar who has provided warm, positive encouragement, calmed my panic attacks, occasionally called a spade a spade but, most importantly, constantly challenged me to chart my own way forward. -

The Ancient Geography of India

िव�ा �सारक मंडळ, ठाणे Title : Ancient Geography of India : I : The Buddhist Period Author : Cunningham, Alexander Publisher : London : Trubner and Co. Publication Year : 1871 Pages : 628 गणपुस्त �व�ा �सारत मंडळाच्ा “�ंथाल्” �तल्पा्गर् िनिमर्त गणपुस्क िन�म्ी वषर : 2014 गणपुस्क �मांक : 051 CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Cornell University Library DS 409.C97 The ancient geqgraphv.of India 3 1924 023 029 485 f mm Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023029485 THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY ov INDIA. A ".'i.inMngVwLn-j inl^ : — THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY INDIA. THE BUDDHIST PERIOD, INCLUDING THE CAMPAIGNS OP ALEXANDER, AND THE TRAVELS OF HWEN-THSANG. ALEXANDER CUNNINGHAM, Ui.JOB-GBirBBALj BOYAL ENGINEEBS (BENGAL BETIBBD). " Venun et terrena demoDstratio intelligatar, Alezandri Magni vestigiiB insistamns." PHnii Hist. Nat. vi. 17. WITS TSIRTBBN MAPS. LONDON TEUBNER AND CO., 60, PATERNOSTER ROW. 1871. [All Sights reserved.'] {% A\^^ TATLOB AND CO., PEIKTEES, LITTLE QUEEN STKEET, LINCOLN'S INN EIELDS. MAJOR-Q-ENEEAL SIR H. C. RAWLINSON, K.G.B. ETC. ETC., WHO HAS HIMSELF DONE SO MUCH ^ TO THROW LIGHT ON THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY OP ASIA, THIS ATTEMPT TO ELUCIDATE A PARTIODLAR PORTION OF THE SUBJKcr IS DEDICATED BY HIS FRIEND, THE AUTHOR. PEEFACE. The Geography of India may be conveniently divided into a few distinct sections, each broadly named after the prevailing religious and political character of the period which it embraces, as the Brahnanical, the Buddhist^ and the Muhammadan. -

Ganga River Basin Management Plan - 2015

Ganga River Basin Management Plan - 2015 Main Plan Document January 2015 by Cosortiu of 7 Idia Istitute of Techologys (IITs) IIT IIT IIT IIT IIT IIT IIT Bombay Delhi Guwahati Kanpur Kharagpur Madras Roorkee In Collaboration with IIT IIT CIFRI NEERI JNU PU NIT-K DU BHU Gandhinagar NIH ISI Allahabad WWF Roorkee Kolkata University India GRBMP Work Structure GRBMP – January 2015: Main Plan Document Preface In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-sections (1) and (3) of Section 3 of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 (29 of 1986), the Central Government constituted the National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA) as a planning, financing, monitoring and coordinating authority for strengthening the collective efforts of the Central and State Government for effective abatement of pollution and conservation of the river Ganga. One of the important functions of the NGRBA is to prepare and implement a Ganga River Basin Maageet Pla G‘BMP. A Cosotiu of see Idia Istitute of Tehologs IITs) was given the responsibility of preparing the GRBMP by the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF), GOI, New Delhi. A Memorandum of Agreement (MoA) was therefore signed between the 7 IITs (IITs Bombay, Delhi, Guwahati, Kanpur, Kharagpur, Madras and Roorkee) and MoEF for this purpose on July 6, 2010. This is the Main Plan Document (MPD) that briefly describes (i) river Ganga in basin perspective, (ii) management of resources in Ganga Basin, (iii) philosophy of GRBMP, (iv) issues and concerns of the NRGB Environment, (v) suggestions and recommendations in the form of various Missions, and (vi) a framework for effective implementation of the recommendations. -

Village Details

VILLAGE LIST WITH POPULATION LESS THAN 2000 No. of S No. Zone Name of State District Name of Base Branch Name of village Population Household 1 AGARTALA MANIPUR BISHENPUR BISHENPUR NINGTHOUKHONG AWANG 1540 181 2 AGARTALA MANIPUR BISHENPUR BISHENPUR SUNUSHIPHAI 1388 253 3 AGARTALA MANIPUR BISHENPUR BISHENPUR YUMNUM KHUNOU 1116 188 4 AGARTALA MIZORAM AIZAWL AIZAWL ZOHMUN 1363 235 5 AGARTALA TRIPURA KHOWAI BAGANBAZAR HALONG MATAI 1485 348 6 AGARTALA TRIPURA KHOWAI BAGANBAZAR PREM SING ORANG 1127 238 7 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR ABDULLAPUR 400 67 8 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR DULAKANDI 900 113 9 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR DURGAPUR 1000 125 10 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR EAST SAKAIBARI 1180 135 11 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR KUTERBASA 550 92 12 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR MADHYA CHANDRAPUR 975 122 13 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR NATHPARA 900 112 14 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR NORTH CHANDRA PUR 950 135 15 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR RADHANAGAR 500 72 16 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR SOUTH SAKAIBARI 800 133 17 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR WEST CHANDRAPUR 1050 150 18 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR WEST RAGHNA 600 86 19 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR WEST SAKAI BARI 1125 142 20 AGARTALA TRIPURA WEST TRIPURA MOHANPUR KAMBUKCHERRA 1908 317 21 AHMEDABAD GUJRAT AMRELI AMRELI BHUTIA 1800 40 22 AHMEDABAD GUJRAT AMRELI AMRELI GIRIA 1900 30 23 AHMEDABAD GUJRAT AMRELI AMRELI SANGADERI