Museum Brochure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Story-Of-Ancient-Indian-People

The Story Of The Ancient Indus People Mohenjo-daro - Harappa Yussouf Shaheen Culture and Tourism Department, Government of Sindh, Karachi All Rights Reserved Book’S name: The Story of the Ancient Indus People Mohenjo Daro-Harappa Writer: Yussouf Shaheen TitleL Danish Khan Layout: Imtiaz Ali Ansari Publisher: Culture and Tourism Department, Government of Sindh, Karachi Printer: New Indus Printing Press sukkur Price: Rs.700/- Can be had from Culture, Tourism, and Antiquities Department Book shop opposite MPA Hostel Sir Ghulam Hussain Hidaytullah Road Karachi-74400 Phone 021-99206073 Yussouf Shaheen The Story Of The Ancient Indus People Mohenjo-daro - Harappa Books authored by Yussouf Shaheen: Rise and Fall of Sanskrit Fall of Native Languages of the Americas Slave Nations Under British Monarchs Artificial Borders of the World Rise and Fall of gods – In Historical Perspective William the Bastard and his descendants World Confederation of the Peoples The World of Conquerors Truth Untold Seven other books in Sindhi and Urdu In the memory of my friend Abdul Karim Baloch A TV icon fully reflecting the greatness and wisdom of Mohenjo-daro and blessed with the enduring perception of a Weapon-Free Society created in the Indus Valley Civilization. © Yussouf Shaheen 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying recording or otherwise , without the prior permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Peon Fatehgarh.Pdf

Department of Local Government Punjab (Punjab Municipal Bhawan, Plot No.-3, Sector-35 A, Chandigarh) Detail of application for the posts of Peon (Service Group-D) reserved for Disabled Persons in the cadre of Municipal Corporations and Municipal Councils-Nagar Panchayats in Punjab Sr. App Name of Candidate Address Date of Birth VH, HH, OH No. No. and Father’s Name etc. %age of Sarv Shri/ Smt./ disability Miss 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 191 Narinder Singh S/o Village Atta Pur, P.O. 26.03.1986 OH 45% Shambu Ram Charnarthal Kalan, Fatehgarh Sahib. 2 192 Gurjant Singh S/o Village Nariana, P.O. 20.05.1983 OH 60% Avtar Singh Bhagrana, Teh Bassi Pathana, Distt. Fatehgarh Sahib. 3 386 Gurwinder Singh S/o V.P.O Hallal Pur, Teh. 01.01.1991 OH 70% Sukhvinder Singh and Distt. Fatehgarh Sahib 4 411 Lakhwinder Singh Vill. Fateh Pur Araian, 04.02.1992 OH 85% S/o Meva Singh Teh. Basi Bathana, Distt.- Fateh Garh Sahib PB- 140412 5 501 Satpal Singh S/o V.P.O Malko Majra, Distt. 17.02.1981 OH 50% Hari Singh Fatehgarh Sahib 6 563 Balwant Singh S/o Village Dedrha, PO 20.12.1992 OH 70% Bahadur Singh Kumbadgarh, Fatehgarh Sahib 7 665 Narinder Singh S/o Vill. Dadiana, Teh. Bassi 05.10.1986 OH 100% Shamsher Singh Pathana, PO Rupalheri, District Fathegarh Sahib. 8 752 Tejvir Singh S/o W.No: 12, Amloh, Distt: 03.07.1990 OH 40% Chhajju Ram Fatehgarh Sahib. 9 885 Jagjit Singh S/o Vill. -

Geography of Early Historical Punjab

Geography of Early Historical Punjab Ardhendu Ray Chatra Ramai Pandit Mahavidyalaya Chatra, Bankura, West Bengal The present paper is an attempt to study the historical geography of Punjab. It surveys previous research, assesses the emerging new directions in historical geography of Punjab, and attempts to understand how archaeological data provides new insights in this field. Trade routes, urbanization, and interactions in early Punjab through material culture are accounted for as significant factors in the overall development of historical and geographical processes. Introduction It has aptly been remarked that for an intelligent study of the history of a country, a thorough knowledge of its geography is crucial. Richard Hakluyt exclaimed long ago that “geography and chronology are the sun and moon, the right eye and left eye of all history.”1 The evolution of Indian history and culture cannot be rightly understood without a proper appreciation of the geographical factors involved. Ancient Indian historical geography begins with the writings of topographical identifications of sites mentioned in the literature and inscriptions. These were works on geographical issues starting from first quarter of the nineteenth century. In order to get a clear understanding of the subject matter, now we are studying them in different categories of historical geography based on text, inscriptions etc., and also regional geography, cultural geography and so on. Historical Background The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the 2 JSPS 24:1&2 rivers Sutlej, Beas, Ravi, Chenab and Jhelum. -

List of Sewa Kendras Retained

List 2 - List of Sewa Kendras Retained List 2 - List of Sewa Kendras Retained S No District Sewa Kendra Name and Location Center Code Type 1 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, HO, Kitchlu Chownk PB-049-00255-U025 Type-I 2 Amritsar MC Majitha Near Telephone Exchange PB-049-00255-U001 Type-II 3 Amritsar MC Jandiala Near Bus Stand PB-049-00255-U002 Type-II 4 Amritsar Chamrang Road (Park) PB-049-00255-U004 Type-II 5 Amritsar Gurnam Nagar/Sakatri Bagh PB-049-00255-U008 Type-II 6 Amritsar Lahori Gate PB-049-00255-U011 Type-II 7 Amritsar Kot Moti Ram PB-049-00255-U015 Type-II 8 Amritsar Zone No 6 - Basant Park, Basant Avenue PB-049-00255-U017 Type-II Zone No 7 - PWD (B&R) Office Opp. 9 Amritsar PB-049-00255-U019 Type-II Celebration Mall 10 Amritsar Zone No 8- Japani Mill (Park), Chherata PB-049-00255-U023 Type-II Suwidha Centre, DTO Office, Ram Tirath 11 Amritsar PB-049-00255-U026 Type-II Road, Asr 12 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, Ajnala PB-049-00255-U028 Type-II Suwidha Centre, Batala Road, Baba 13 Amritsar PB-049-00255-U029 Type-II Bakala Sahib 14 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, Attari PB-049-00255-U031 Type-II 15 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, Lopoke PB-049-00255-U032 Type-II 16 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, Tarsikka PB-049-00255-U034 Type-II 17 Amritsar Ajnala PB-049-00255-R001 Type-II 18 Amritsar Ramdass PB-049-00255-R002 Type-III 19 Amritsar Rajasansi PB-049-00259-R003 Type-II 20 Amritsar Market Committee Rayya Office PB-049-00259-R005 Type-II 21 Amritsar Jhander PB-049-00255-R025 Type-III 22 Amritsar Chogawan PB-049-00255-R027 Type-III 23 Amritsar Jasrur PB-049-00255-R035 -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Of Dr. R.S. Bisht Joint Director General (Retd.) Archaeological Survey of India & Padma Shri Awardee, 2013 Address: 9/19, Sector-3, Rajendranagar, Sahibabad, Ghaziabad – 201005 (U.P.) Tel: 0120-3260196; Mob: 09990076074 Email: [email protected] i Contents Pages 1. Personal Data 1-2 2. Excavations & Research 3-4 3. Conservation of Monuments 5 4. Museum Activities 6-7 5. Teaching & Training 8 6. Research Publications 9-12 7. A Few Important Research papers presented 13-14 at Seminars and Conferences 8. Prestigious Lectures and Addresses 15-19 9. Memorial Lectures 20 10. Foreign Countries and Places Visited 21-22 11. Members on Academic and other Committees 23-24 12. Setting up of the Sarasvati Heritage Project 25 13. Awards received 26-28 ii CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Personal Data Name : DR. RAVINDRA SINGH BISHT Father's Name : Lt. Shri L. S. Bisht Date of Birth : 2nd January 1944 Nationality : Indian by birth Permanent Address : 9/19, Sector-3, Rajendranagar, Sahibabad Ghaziabad – 201 005 (U.P.) Academic Qualifications Degree Subject University/ Institution Year M.A . Ancient Indian History and Lucknow University, 1965. Culture, PGDA , Prehistory, Protohistory, School of Archaeology 1967 Historical archaeology, Conservation (Archl. Survey of India) of Monuments, Chemical cleaning & preservation, Museum methods, Antiquarian laws, Survey, Photography & Drawing Ph. D. Emerging Perspectives of Kumaun University 2002. the Harappan Civilization in the Light of Recent Excavations at Banawali and Dholavira Visharad Hindi Litt., Sanskrit, : Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, Prayag 1958 Sahityaratna, Hindi Litt. -do- 1960 1 Professional Experience 35 years’ experience in Archaeological Research, Conservation & Environmental Development of National Monuments and Administration, etc. -

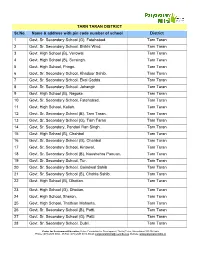

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

Physical Geography of the Punjab

19 Gosal: Physical Geography of Punjab Physical Geography of the Punjab G. S. Gosal Formerly Professor of Geography, Punjab University, Chandigarh ________________________________________________________________ Located in the northwestern part of the Indian sub-continent, the Punjab served as a bridge between the east, the middle east, and central Asia assigning it considerable regional importance. The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the rivers - Satluj, Beas, Ravi, Chanab and Jhelam. The paper provides a detailed description of Punjab’s physical landscape and its general climatic conditions which created its history and culture and made it the bread basket of the subcontinent. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Herodotus, an ancient Greek scholar, who lived from 484 BCE to 425 BCE, was often referred to as the ‘father of history’, the ‘father of ethnography’, and a great scholar of geography of his time. Some 2500 years ago he made a classic statement: ‘All history should be studied geographically, and all geography historically’. In this statement Herodotus was essentially emphasizing the inseparability of time and space, and a close relationship between history and geography. After all, historical events do not take place in the air, their base is always the earth. For a proper understanding of history, therefore, the base, that is the earth, must be known closely. The physical earth and the man living on it in their full, multi-dimensional relationships constitute the reality of the earth. There is no doubt that human ingenuity, innovations, technological capabilities, and aspirations are very potent factors in shaping and reshaping places and regions, as also in giving rise to new events, but the physical environmental base has its own role to play. -

Mohenjo-Daro's Small Public Structures: Heterarchy, Collective Action, and a Re- Visitation of Old Interpretations with GIS and 3D Modelling

Accepted Manuscript Title: Mohenjo-daro's Small Public Structures: Heterarchy, Collective Action, and a Re- visitation of Old Interpretations with GIS and 3D Modelling Author: Adam S. Green Journal: Cambridge Archaeological Journal DOI:10.1017/S0959774317000774 Submitted: 15 December 2016 Accepted: 6 September 2017 Revised: 4 July 2017 1 MOHENJO-DARO’S SMALL PUBLIC STRUCTURES: HETERARCHY, COLLECTIVE 2 ACTION, AND A RE-VISITATION OF OLD INTERPRETATIONS WITH GIS AND 3D 3 MODELLING 4 5 Abstract 6 7 Together, the concepts of heterarchy and collective action offer potential explanations for how 8 early state societies may have established high degrees of civic coordination and sophisticated 9 craft industries in absence of exclusionary political strategies or dominant centralised political 10 hierarchies. The Indus civilisation (c.2600-1900 B.C.) appears to have been heterarchical, which 11 raises critical questions about how its infrastructure facilitated collective action. Digital re- 12 visitation of early excavation reports provides a powerful means of re-examining the nuances of 13 the resulting datasets and the old interpretations offered to explain them. In an early report on 14 excavations at Mohenjo-daro, the Indus civilisation’s largest city, Ernest Mackay described a 15 pair of small non-residential structures at a major street intersection as a “hostel” and “office” for 16 the “city fathers.” In this article, Mackay’s interpretation that these structures had a public 17 orientation is tested using a geographical information systems approach (GIS) and 3D models 18 derived from plans and descriptions in his report. In addition to supporting aspects of Mackay’s 19 interpretation, the resulting analysis indicates that Mohenjo-daro’s architecture changed through 20 time, increasingly favouring smaller houses and public structures. -

Village Details

VILLAGE LIST WITH POPULATION LESS THAN 2000 No. of S No. Zone Name of State District Name of Base Branch Name of village Population Household 1 AGARTALA MANIPUR BISHENPUR BISHENPUR NINGTHOUKHONG AWANG 1540 181 2 AGARTALA MANIPUR BISHENPUR BISHENPUR SUNUSHIPHAI 1388 253 3 AGARTALA MANIPUR BISHENPUR BISHENPUR YUMNUM KHUNOU 1116 188 4 AGARTALA MIZORAM AIZAWL AIZAWL ZOHMUN 1363 235 5 AGARTALA TRIPURA KHOWAI BAGANBAZAR HALONG MATAI 1485 348 6 AGARTALA TRIPURA KHOWAI BAGANBAZAR PREM SING ORANG 1127 238 7 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR ABDULLAPUR 400 67 8 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR DULAKANDI 900 113 9 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR DURGAPUR 1000 125 10 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR EAST SAKAIBARI 1180 135 11 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR KUTERBASA 550 92 12 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR MADHYA CHANDRAPUR 975 122 13 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR NATHPARA 900 112 14 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR NORTH CHANDRA PUR 950 135 15 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR RADHANAGAR 500 72 16 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR SOUTH SAKAIBARI 800 133 17 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR WEST CHANDRAPUR 1050 150 18 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR WEST RAGHNA 600 86 19 AGARTALA TRIPURA NORTH TRIPURA CHANDRAPUR WEST SAKAI BARI 1125 142 20 AGARTALA TRIPURA WEST TRIPURA MOHANPUR KAMBUKCHERRA 1908 317 21 AHMEDABAD GUJRAT AMRELI AMRELI BHUTIA 1800 40 22 AHMEDABAD GUJRAT AMRELI AMRELI GIRIA 1900 30 23 AHMEDABAD GUJRAT AMRELI AMRELI SANGADERI -

APPLICATION for GRANTS UNDER the National Resource Centers and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships

U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202-5335 APPLICATION FOR GRANTS UNDER THE National Resource Centers and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships CFDA # 84.015A PR/Award # P015A180057 Gramts.gov Tracking#: GRANT12659095 OMB No. , Expiration Date: Closing Date: Jun 25, 2018 PR/Award # P015A180057 **Table of Contents** Form Page 1. Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 e3 2. Standard Budget Sheet (ED 524) e6 3. Assurances Non-Construction Programs (SF 424B) e8 4. Disclosure Of Lobbying Activities (SF-LLL) e10 5. ED GEPA427 Form e11 Attachment - 1 (GEPA Statement) e12 6. Grants.gov Lobbying Form e13 7. Dept of Education Supplemental Information for SF-424 e14 8. ED Abstract Narrative Form e15 Attachment - 1 (SAC Abstract,) e16 9. Project Narrative Form e18 Attachment - 1 (TABLE OF CONTENTS) e19 Attachment - 2 (South Asia Center Proposal Narrative 6.19.18) e20 10. Other Narrative Form e70 Attachment - 1 (DESCRIPTION_Diverse_Perspectives) e71 Attachment - 2 (Description_Government_Service_Careers) e72 Attachment - 3 (ACRONYM KEY) e73 Attachment - 4 (Appendix A) e74 Attachment - 5 (Appendix B Course List) e103 Attachment - 6 (Appendix C PMF) e111 Attachment - 7 (Appendix D) e117 Attachment - 8 (FY 2018 NRC_FLAS Profile Form) e125 11. Budget Narrative Form e126 Attachment - 1 (sacnrcflasbudget FINAL_1) e127 This application was generated using the PDF functionality. The PDF functionality automatically numbers the pages in this application. Some pages/sections of this application may contain 2 sets of page numbers, one set created by the applicant and the other set created by e-Application's PDF functionality. Page numbers created by the e-Application PDF functionality will be preceded by the letter e (for example, e1, e2, e3, etc.). -

Telephone-List (As on 4-3-2014))

Telephone-List (As on 4-3-2014)) Sr. Designation/Name of the officer Office No Residence No. Fax No. or No Mobile No. 1. F.C.(R) Punjab Sh. N.S. Kang 2741387-2743854 2794900 Fax. 2741762 98761-39966 2. Commissioner Pta. Div. Pta. Sh. Ajit Singh Pannu 2311324 2311325 98722-30897, Fax. 2311329 (P.A. Sh. N.S. Bajwa 94631-31176, Supdt. Sh. Hans Raj 98156-46710, ( Supdt. Smt. Mohini Arora, 93160-56730) 3. D.C. Fatehgarh Sahib Sh. Arun Sekhri 232215/221340 221341 (Naib Singh PA 97800-32114) 98722-21702 ( [email protected], [email protected] ) 4. ADC Fatehgarh Sahib Sh. M.S. Jaggi 232216 (Smt. Usha Rani Supdt.1, 85560-00563) 97800-39112 5. A.C.(G) Miss Harjot Kaur 232165 ( Smt. Sunita Rani Steno 80540-17475) 97801-99101 6. Extra Assistant Commissioner Sh Udeydeep Singh, PCS , 98144-12141, 08924000001 7. Extra Assistant Commissioner Miss Ravjot Grewal , PCS 8283854385 8. D.R.O.Sh. Daljit Singh Chhina 232838 (Sh. Randhir Singh Steno 98729-84988) 98779-00006 9. D.T.O.Sh. Jagdeep Singh Brar (Manit Singh Jr. Asstt. 99141-57900) (Steno Sh. Dharminder Singh 9501433900) 98150-67979 10. ADTO Sh. Simranjit Singh 76960-60130 11. Sh. Rakesh Gupta MV 98728-07029 12. S.O.DTO Office, Sh.Rajesh Kumar 2359228 P 95929-12407 13. AETC Sh. Magnesh Sethi (IST MGG S. Nachhattar S. 98725-63825) 232183 (PA Sh. Harpreet Singh 99141-52049) 98729-10037 14. ETO (Excise) Sh Balwinder Singh 232183 99880-25419 15. ETO FGS Sh. Jaspal Singh 232183 (ETO FGS Sh. Hardeep S. 75083-29077) 82888-34095 16. -

Download Book

EXCAVATIONS AT RAKHIGARHI [1997-98 to 1999-2000] Dr. Amarendra Nath Archaeological Survey of India 1 DR. AMARENDRA NATH RAKHIGARHI EXCAVATION Former Director (Archaeology) ASI Report Writing Unit O/o Superintending Archaeologist ASI, Excavation Branch-II, Purana Qila, New Delhi, 110001 Dear Dr. Tewari, Date: 31.12.2014 Please refer to your D.O. No. 24/1/2014-EE Dated 5th June, 2014 regarding report writing on the excavations at Rakhigarhi. As desired, I am enclosing a draft report on the excavations at Rakhigarhi drawn on the lines of the “Wheeler Committee Report-1965”. The report highlights the facts of excavations, its objective, the site and its environment, site catchment analysis, cultural stratigraphy, structural remains, burials, graffiti, ceramics, terracotta, copper, other finds with two appendices. I am aware of the fact that the report under submission is incomplete in its presentation in terms modern inputs required in an archaeological report. You may be aware of the fact that the ground staff available to this section is too meagre to cope up the work of report writing. The services of only one semiskilled casual labour engaged to this section has been withdrawn vide F. No. 9/66/2014-15/EB-II496 Dated 01.12.2014. The Assistant Archaeologist who is holding the charge antiquities and records of Rakhigarhi is available only when he is free from his office duty in the Branch. The services of a darftsman accorded to this unit are hardly available. Under the circumstances it is requested to restore the services of one semiskilled casual labour earlier attached to this unit and draftsman of the Excavation Branch II Purana Quila so as to enable the unit to function smoothly with limited hands and achieve the target.