The Mughal Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mughal Paintings of Hunt with Their Aristocracy

Arts and Humanities Open Access Journal Research Article Open Access Mughal paintings of hunt with their aristocracy Abstract Volume 3 Issue 1 - 2019 Mughal emperor from Babur to Dara Shikoh there was a long period of animal hunting. Ashraful Kabir The founder of Mughal dynasty emperor Babur (1526-1530) killed one-horned Department of Biology, Saidpur Cantonment Public College, rhinoceros and wild ass. Then Akbar (1556-1605) in his period, he hunted wild ass Nilphamari, Bangladesh and tiger. He trained not less than 1000 Cheetah for other animal hunting especially bovid animals. Emperor Jahangir (1606-1627) killed total 17167 animals in his period. Correspondence: Ashraful Kabir, Department of Biology, He killed 1672 Antelope-Deer-Mountain Goats, 889 Bluebulls, 86 Lions, 64 Rhinos, Saidpur Cantonment Public College, Nilphamari, Bangladesh, 10348 Pigeons, 3473 Crows, and 10 Crocodiles. Shahjahan (1627-1658) who lived 74 Email years and Dara Shikoh (1657-1658) only killed Bluebull and Nur Jahan killed a tiger only. After study, the Mughal paintings there were Butterfly, Fish, Bird, and Mammal. Received: December 30, 2018 | Published: February 22, 2019 Out of 34 animal paintings, birds and mammals were each 16. In Mughal pastime there were some renowned artists who involved with these paintings. Abdus Samad, Mir Sayid Ali, Basawan, Lal, Miskin, Kesu Das, Daswanth, Govardhan, Mushfiq, Kamal, Fazl, Dalchand, Hindu community and some Mughal females all were habituated to draw paintings. In observed animals, 12 were found in hunting section (Rhino, Wild Ass, Tiger, Cheetah, Antelope, Spotted Deer, Mountain Goat, Bluebull, Lion, Pigeon, Crow, Crocodile), 35 in paintings (Butterfly, Fish, Falcon, Pigeon, Crane, Peacock, Fowl, Dodo, Duck, Bustard, Turkey, Parrot, Kingfisher, Finch, Oriole, Hornbill, Partridge, Vulture, Elephant, Lion, Cow, Horse, Squirrel, Jackal, Cheetah, Spotted Deer, Zebra, Buffalo, Bengal Tiger, Camel, Goat, Sheep, Antelope, Rabbit, Oryx) and 6 in aristocracy (Elephant, Horse, Cheetah, Falcon, Peacock, Parrot. -

Nimatullahi Sufism and Deccan Bahmani Sultanate

Volume : 4 | Issue : 6 | June 2015 ISSN - 2250-1991 Research Paper Commerce Nimatullahi Sufism and Deccan Bahmani Sultanate Seyed Mohammad Ph.D. in Sufism and Islamic Mysticism University of Religions and Hadi Torabi Denominations, Qom, Iran The presentresearch paper is aimed to determine the relationship between the Nimatullahi Shiite Sufi dervishes and Bahmani Shiite Sultanate of Deccan which undoubtedly is one of the key factors help to explain the spread of Sufism followed by growth of Shi’ism in South India and in Indian sub-continent. This relationship wasmutual andin addition to Sufism, the Bahmani Sultanate has also benefited from it. Furthermore, the researcher made effortto determine and to discuss the influential factors on this relation and its fruitful results. Moreover, a brief reference to the history of Muslims in India which ABSTRACT seems necessary is presented. KEYWORDS Nimatullahi Sufism, Deccan Bahmani Sultanate, Shiite Muslim, India Introduction: are attributable the presence of Iranian Ascetics in Kalkot and Islamic culture has entered in two ways and in different eras Kollam Ports. (Battuta 575) However, one of the major and in the Indian subcontinent. One of them was the gradual ar- important factors that influence the development of Sufism in rival of the Muslims aroundeighth century in the region and the subcontinent was the Shiite rule of Bahmani Sultanate in perhaps the Muslim merchants came from southern and west- Deccan which is discussed briefly in this research paper. ern Coast of Malabar and Cambaya Bay in India who spread Islamic culture in Gujarat and the Deccan regions and they can Discussion: be considered asthe pioneers of this movement. -

An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms Among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar

JIOWSJournal of Indian Ocean World Studies An Abode of Islam under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar Mahmood Kooria To cite this article: Kooria, Mahmood. “An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar.” Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies, 1 (2017), pp. 89-109. More information about the Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies can be found at: jiows.mcgill.ca © Mahmood Kooria. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Li- cense CC BY NC SA, which permits users to share, use, and remix the material provide they give proper attribu- tion, the use is non-commercial, and any remixes/transformations of the work are shared under the same license as the original. Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies, 1 (2017), pp. 89-109. © Mahmood Kooria, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 | 89 An Abode of Islam under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar Mahmood Kooria* Leiden University, Netherlands ABSTRACT When Vasco da Gama asked the Zamorin (ruler) of Calicut to expel from his domains all Muslims hailing from Cairo and the Red Sea, the Zamorin rejected it, saying that they were living in his kingdom “as natives, not foreigners.” This was a marker of reciprocal understanding between Muslims and Zamorins. When war broke out with the Portuguese, Muslim intellectuals in the region wrote treatises and delivered sermons in order to mobilize their community in support of the Zamorins. -

SYNOPSIS of DEBATE ______(Proceedings Other Than Questions and Answers) ______Friday, March 19, 2021 / Phalguna 28, 1942 (Saka) ______OBSERVATION by the CHAIR 1

RAJYA SABHA _______ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATE _______ (Proceedings other than Questions and Answers) _______ Friday, March 19, 2021 / Phalguna 28, 1942 (Saka) _______ OBSERVATION BY THE CHAIR 1. MR. CHAIRMAN: Hon. Members, I have an appeal to make in view of the reports coming from certain States that the virus pandemic is spreading. So, I only appeal to all the Members of Parliament who are here, who are there in their respective fields to be extra careful. I know that you are all public representatives, You can't live in isolation. At the same time while dealing with people, meeting them or going to your constituency or other areas, be careful. Strictly follow the advice given by the Healthy Ministry, Home Ministry, Central Government as well as the guidelines issued by the State Governments concerned from time to time and see to it that they are followed. My appeal is not only to you, but also to the people in general. The Members of Parliament should take interest to see that the people are guided properly. We are seeing that though the severity has come down, but the cases are spreading here and there. It is because the people in their respective areas are not following discipline. This is a very, very important aspect. We should not allow the situation to deteriorate. We are all happy, the world is happy, the country is happy, people are happy. We have been able to contain it, and we were hoping that we would totally succeed. Meanwhile, these ___________________________________________________ This Synopsis is not an authoritative record of the proceedings of the Rajya Sabha. -

Invest in Dallas - Fort Worth Area Grab the Property Before It Is out in the Market Text: 219-588-1538

SEPTEMBER 2019 PAGE 1 Globally Recognized Editor-in-Chief: Azeem A. Quadeer, M.S., P.E. SEPTEMBER 2019 Vol 10, Issue 9 Federal agents can search your phone at the US border, even if you’re a US citizen Customs officers are legally allowed to before such an invasive search. search travelers’ personal electronics with- out a warrant — whether they’re visitors Travelers can refuse access to their devic- or American citizens. es, but customs officers are not obligated to allow someone into the country. A Harvard student said he was recently denied entry to the US after officers ques- For now, lawyers recom- tioned him about his religion and then mend that travelers carry searched his phone and laptop and burner phones, en- Elyas Mohammed State Executive Com- found that his friends had written crypt their devices, resident of Lebanon, when he tried to mittee Member at North Carolina Demo- anti-American social-media or simply not enter the US to start his first semester at cratic Party with Presidential hopeful Beto posts. bring electron- Harvard. O’Rourke ics at all. Rights groups have When Ajjawi told The Harvard Crimson that sued the US INSIDE you’re customs officers at Boston’s Logan Inter- government en- national Airport demanded he unlock over the his phone and laptop and then spent five prac- hours searching the devices. tice, He said the officers asked him about his ter- ISNA Convention 2019 P-2 religion and about political, anti-Ameri- ing the can posts his friends had made on social Visa availability Dates P-8 United media. -

BAYANA the First Lavishly Illustrated and Comprehensive Record of the Historic Bayana Region

BAYANA The first lavishly illustrated and comprehensive record of the historic Bayana region Bayana in Rajasthan, and its monuments, challenge the perceived but established view of the development of Muslim architecture and urban form in India. At the end of the 12th century, early conquerors took the mighty Hindu fort, building the first Muslim city below on virgin ground. They later reconfigured the fort and constructed another town within it. These two towns were the centre of an autonomous region during the 15th and 16th centuries. Going beyond a simple study of the historic, architectural and archaeological remains, this book takes on the wider issues of how far the artistic traditions of Bayana, which developed independently from those of Delhi, later influenced north Indian architecture. It shows how these traditions were the forerunners of the Mughal architectural style, which drew many of its features from innovations developed first in Bayana. Key Features • The first comprehensive account of this historic region • Offers a broad reinvestigation of North Indian Muslim architecture through a case study of a desert fortress MEHRDAD SHOKOOHY • Includes detailed maps of the sites: Bayana Town, the Garden City of NATALIE H. SHOKOOHY Sikandra and the Vijayamandargarh or Tahangar Fort with detailed survey of its fortifications and its elaborate gate systems • Features photographs and measured surveys of 140 monuments and epigraphic records from the 13th to the end of the 16th century – including mosques, minarets, waterworks, domestic dwellings, mansions, ‘īdgāhs (prayer walls) and funerary edifices • Introduces historic outlying towns and their monuments in the region such as Barambad, Dholpur, Khanwa and Nagar-Sikri (later to become Fathpur Sikri) • Demonstrates Bayana’s cultural and historic importance in spite of its present obscurity and neglect BAYANA • Adds to the record of India’s disappearing historic heritage in the wake of modernisation. -

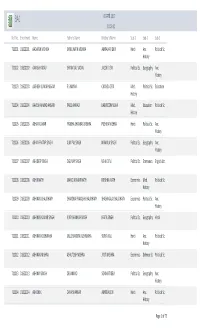

01 माच 2017 10:03:32 Roll No. Enrollment Name Father's Name

BA1 01 माच 2017 10:03:32 Roll No. Enrollment Name Father's Name Mother's Name Sub-1 Sub-2 Sub-3 711001 D1620001 AADARSH MISHRA SHREE NATH MISHRA AMRAVATI DEVI Hindi Anc. Political Sc. History 711002 D1620002 AAKASH YADAV SHYAM LAL YADAV JAGDEI DEVI Political Sc. Geography Anc. History 711003 D1620003 AASHISH KUMAR NIGAM R S NAINVI CHANDA DEVI Med. Political Sc. Education History 711004 D1620004 AAVESH AHMAD ANSARI RAIES AHMAD KABI ROON NISHA Med. Education Political Sc. History 711005 D1620005 ABHAY KUMAR PRABHA SHANKAR MISHRA PUSHPA MISHRA Hindi Political Sc. Anc. History 711006 D1620006 ABHAY PRATAP SINGH AJAY PAL SINGH NIRMALA SINGH Political Sc. Geography Anc. History 711007 D1620007 ABHIDEEP SINGH DIGVIJAY SINGH USHA DEVI Political Sc. Economics English Litt. 711008 D1620008 ABHIK NATH MANOJ KUMAR NATH KRISHNA NATH Economics Med. Political Sc. History 711009 D1620009 ABHINAV CHAUDHARY CHANDRA PRAKASH CHAUDHARY SHASHIKALA CHAUDHARY Economics Political Sc. Anc. History 711010 D1620010 ABHINAV KUMAR SINGH VIJAY SHANKAR SINGH REETA SINGH Political Sc. Geography Hindi 711011 D1620011 ABHINAV KUSHWAHA MULCHANDRA KUSHWAHA SURYA KALI Hindi Anc. Political Sc. History 711012 D1620012 ABHINAV MISHRA ASHUTOSH MISHRA JYOTI MISHRA Economics Defence St. Political Sc. 711013 D1620013 ABHINAY SINGH DEVANAND SONMATI DEVI Political Sc. Geography Anc. History 711014 D1620014 ABHISHEK DAYA SHANKAR AMRITA DEVI Hindi Anc. Political Sc. History Page 1 of 73 Roll No. Enrollment Name Father's Name Mother's Name Sub-1 Sub-2 Sub-3 711015 D1620015 ABHISHEK DWIVEDI KULDEEP KUMAR DWIVEDI KAVITA DEVI Economics Anc. Political Sc. History 711016 D1620016 ABHISHEK GUPTA SHARAD GUPTA SUSHILA GUPTA Geography Med. -

Delhi Sultanate

DELHI SULTANATE The period from 1206 to 1526 in India history is known as Sultanate period. Slave Dynasty In 1206 Qutubuddin Aibak made India free of Ghazni’s control. Rulers who ruled over India and conquered new territories during the period 1206-1290 AD. are known as belonging to Slave dynasty. Qutubuddin Aibak He came from the region of Turkistan and he was a slave of Mohammad Ghori. He ruled as a Sultan from 1206 to 1210. While playing Polo, he fell from the horse and died in 1210. Aram Shah After Aibak’s death, his son Aram Shah was enthroned at Lahore. In the conflict between Iltutmish and Aram Shah, Iltutmish was victorious. Iltutmish He was slave of Aibak. He belonged to the Ilbari Turk clan of Turkistan. In 1211 Iltutmish occupied the throne of Delhi after killing Aram Shah and successfully ruled upto 1236. Construction of Qutub Minar He completed the unfinished construction of Qutub Minar, which was started by Qutubuddin Aibak. He built the Dhai Din ka Jhopra at Ajmer. Razia Sultan She was the first lady Sultan who ruled for three years, six months and six days. From 1236 to 1240. She appointed Jamaluddin Yakut as highest officer of cavalry. In 1240, the feudal lord (Subedar) of Bhatinda, Ikhtiyaruddin nobles he imprisoned Razia and killed Yakut. To counter her enemies Razia married Altunia and once again attempted to regain power. On 13th October, 1240, near Kaithal when Razia and Altunia were resting under a tree, some dacoits killed them. Balban Set on the throne of Delhi in 1266 and he adopted the name of Ghiyasuddin Balban. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

BABUR NAMA Journal of Emperor Babur

RESOURCES BOOK REVIEW ESSAYS BABUR NAMA Journal of Emperor Babur TRANSLATED FROM TURKISH By ANNETTE SUSANNAH BEVERIDGE NEW DELHI: PENGUIN BOOKS, 2006 385 PAGES, ISBN: 978-0144001491, PAPERBACK Reviewed by Laxman D. Satya riginally written in Turkish by Emperor Babur (1483–1530) Oand translated into Persian by his grandson, Emperor Akbar (1556– 1605), Babur Nama, Journal of Emperor Babur is now available in English, com- plete with maps, tables of the family tree, glossary, list of main characters, an Is- lamic calendar, Babur’s daily prayer, and endnotes that are not too overbearing. Dilip Hiro has done a marvelous job of editing this classic of the autobiographical account of the founder of the Mughal Empire in India that lasted from 1526–1707. It was written in an elab- orate style as a journal or daily diary and records the events in his life and times. From page one, it is obvious that Babur was a highly cultured in- dividual with a meticulous eye for recording details through observa- tion. Even though he was from an elite class of rulers and sultans, in these memoirs he records the lives of ordinary folks like soldiers, ac- robats, musicians, singers, wine drinkers, maajun eaters, weavers, water carriers, lamp keepers, boatmen, thieves, gatekeepers, rebels, dervishes (holy men), Sufis, scholars, youth, pastoralists, peasants, artisans, mer- chants, and traders. Strangely, there is very little mention of women and children other than his immediate family members—his mother, sister, aunts, or daughters—and they are always mentioned with great respect and reverence. Babur was a religious person who meticulously observed prayers and fasting during Ramadan. -

Babur S Creativity from Central Asia to India

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 5, ISSUE 05, MAY 2016 ISSN 2277-8616 Babur’s Creativity From Central Asia To India Rahimov Laziz Abduazizovich Abstract: this report explores about Babur’s Mughal architecture. Additionally, the new style of architecture has made and brought in by Babur in India. As we found out that during those days, in India, the Islamic architecture was developed, however, despite the fact Babur wanted to bring in to that sector his new idea about Timurid style because Indian style of building did not gave pleasure to Babur. Therefore, after the victory over the Lodi he started to change the Indian style and started to build in Temurid scheme. As there are, three mosques and it doubted which one has built by Babur and after making research we have found it in detail. In addition, it has displayed in more detail in the following. Lastly, we followed how Baburid architecture has begun and its development over the years, as well as, it has given an evidence supporting our points. Index Terms: Timurid style, Baburid architecture, Islamic architecture, Indian local traditions, Kabuli Bog' mosque, Sambhal mosque, Baburid mosque. ———————————————————— 1 INTRODUCTION lower from this house. Even though, the house is located in According to the Persian historians, Zakhritdin Muhammad the highest level of the mountain, overall city and streets were Babur Muharram was born in the year 888 AH (February in the view. In the foot of mountain there was built mosque 1483). His father, Omar Sheikh Mirza (1462 - 1494) was the which is known as Jawzi" [3, 29-30p]. -

R[`C Cv[ZX >`UZ¶D W`Tfd ` H`^V

( E8 F F F ,./0,1 234 #)#)* .#,/0 +#,- < 8425?O#$192##618 46$8$+2#$218?7.2123*7$#2 6+@218$16+2694 234$3)9(17 5476354)5612# 6+ +6194$+6$)+ 9461$@6+4 72#$1#7)84$1$6 6##6##$16826847*2 9766*2+$96<$163 24+6)1 4>2+656.$?6> 66 39 )+* " ,,- & G6 # 2 6 ! %% 2# # 5 46 R! #$ O P R 12 234$ ment issue during the Covid 12 234$ sacrifice anyone to meet his Pradesh gets seven Ministers, era and gave enough fodder to 12 234$ the pandemic. Apart from political and governance objec- including Annupriya Patel of n dropping four top level the foreign media to inflict health, Dr Vardhan also held n a major Cabinet overhaul, tives. Aapna Dal (S), an NDA ally IUnion Ministers — Ravi heavy damage on the Modi e was always at the front- two Ministries — science and Iseen as a mid-term appraisal Despite the slogans of and Gujarat has five represen- Shankar Prasad, Prakash Government . Hline shielding the Modi led technology and earth sciences. of his Ministers and resetting “sabka sath sabka vikash,” the tations in the council of Javadekar, Harsh Vardhan, " The others axed a couple of Government’s Covid-19 man- The resignation is seen by Government’s profile post- Cabinet reshuffle has been Ministers. Karnataka is up by Ramesh Pokhriyal “Nishank” ! # hours before the oath-taking agement and Covid-19 vacci- the Government’s critics as an Covid-19 for the next three- based on caste consideration at four Ministers which includes and eight other Ministers — ceremony of new inductions, nation policy, but it did not admission that the pandemic year term, the Prime Minister every level.