An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms Among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nimatullahi Sufism and Deccan Bahmani Sultanate

Volume : 4 | Issue : 6 | June 2015 ISSN - 2250-1991 Research Paper Commerce Nimatullahi Sufism and Deccan Bahmani Sultanate Seyed Mohammad Ph.D. in Sufism and Islamic Mysticism University of Religions and Hadi Torabi Denominations, Qom, Iran The presentresearch paper is aimed to determine the relationship between the Nimatullahi Shiite Sufi dervishes and Bahmani Shiite Sultanate of Deccan which undoubtedly is one of the key factors help to explain the spread of Sufism followed by growth of Shi’ism in South India and in Indian sub-continent. This relationship wasmutual andin addition to Sufism, the Bahmani Sultanate has also benefited from it. Furthermore, the researcher made effortto determine and to discuss the influential factors on this relation and its fruitful results. Moreover, a brief reference to the history of Muslims in India which ABSTRACT seems necessary is presented. KEYWORDS Nimatullahi Sufism, Deccan Bahmani Sultanate, Shiite Muslim, India Introduction: are attributable the presence of Iranian Ascetics in Kalkot and Islamic culture has entered in two ways and in different eras Kollam Ports. (Battuta 575) However, one of the major and in the Indian subcontinent. One of them was the gradual ar- important factors that influence the development of Sufism in rival of the Muslims aroundeighth century in the region and the subcontinent was the Shiite rule of Bahmani Sultanate in perhaps the Muslim merchants came from southern and west- Deccan which is discussed briefly in this research paper. ern Coast of Malabar and Cambaya Bay in India who spread Islamic culture in Gujarat and the Deccan regions and they can Discussion: be considered asthe pioneers of this movement. -

Age of Exploration Flyer

POSTER INSIDE POSTER Age of Exploration A DIGITAL RESOURCE Introduction Explore five centuries of journeys across the globe, scientific discoveries, the expansion of European colonialism, new trade routes, and conflict over territories. Overview This impressive multi-archive collection focuses on “This remarkable collection European, maritime exploration from the earliest voyages of Vasco da Gama and Christopher provides the documentary Columbus, through the age of discovery, the search base to interpret some of the for the ‘New World’, the establishment of European settlements on every continent, to the eventual major movements of the age discovery of the Northwest and Northeast Passages, of exploration. The variety and the race for the Poles. of the sources made available Bringing together material from twelve archives from opens perspectives that should around the world, this collection includes documents challenge students and bring the relating to major events in European maritime history from the voyages of James Cook to the search for period to life. It is a collection John Franklin’s doomed mission to the Northwest that promotes both historical Passage. It contains a host of additional features for analysis and imagination.” teaching, such as an interactive map which presents an in-depth visualisation of over 50 of these Emeritus Professor John Gascoigne influential voyages. University of New South Wales Highlights Material Types • Captain Cook’s secret instructions, ships’ logs and • Le Livre des merveilles by Marco Polo including the • Diaries, journals and ships’ logbooks journals from three voyages of James Cook, written illuminations of Maître d’Egerton – this illuminated Printed and manuscript books by various crew members and Cook himself which relate manuscript compendium dates from c.1410-1412 and • to early British Pacific exploration and the search for is comprised of geographical works and accounts of • Correspondence, notes and ephemera Terra Australis. -

African Diaspora in Medieval Deccan: a Historical Analysis from 14Th to 17Th Century Dr

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 10 Issue 10, October 2020 ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gate as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A African Diaspora in Medieval Deccan: A Historical Analysis from 14th to 17th century Dr. Surendra Kumar, Department of History, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Delhi This Paper was Presented in International Conference organized by Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts(IGNCA), New Delhi on Oct 15, 2014 The African Diaspora in Medieval Deccan offers a new insight about space, political culture, ethnogenesis and Military Labour Market in History of India as well as it provides a new understanding of medieval India from perspective of regional History. This paper traces History of African Diaspora in Medieval Deccan from 14 to 17 century. Tracing issues of Migration in Medieval Deccan, it examines processes of ethnogenesis in African Diaspora and analyses role of space and political culture in shaping contours of ethnogenesis in Medieval Deccan. Further, the paper analyses dimensions of Military Labour market in Medieval Deccan in determining participation of African Diaspora and its impact on evolution of politics in Medieval Deccan. Although, the presence of African Diaspora in the Indian subcontinent has been dated since 10th century onwards, particularly participation in politics from Delhi Sultanate to Bengal is very well documented in primary sources of Ibn Battuta, Muhammad Qasim Ferishta, Jahangir and Others. -

Merit Cum Means Scholarship for BPL Students NOTIFICATION for 2014 -15 As Per G.O.(Rt) No

No. No. Acd/Spc (1)/21240/HSE/2014-15(BPL) Dated: 15/12/2014 DIRECTORATE OF HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION Merit cum Means Scholarship for BPL students NOTIFICATION FOR 2014 -15 As per G.O.(Rt) No. 4935/07/Gl. Edn. dtd. 26/10/2007, Government of Kerala has introduced a comprehensive merit-cum-means scholarship scheme for the Higher Secondary students of Government and Aided schools whose parents or guardians come under the BPL category. The scheme was introduced during 2007 – 2008. The amount of scholarship was fixed at Rs. 5000/-. I. SELECTION OF BENEFICIARIES The beneficiaries are selected at schools by a duly constituted committee as shown below. Selection Committee. A Selection Committee is constituted with the following members for identifying the eligible beneficiaries:- 1. Principal. (Chairperson) 2. Headmaster/Headmistress of the school. (Member) 3. PTA President. (Member) 4. Staff Secretary. (Member) 5. A representative of the teaching staff elected by the staff council. (Member) One of the members shall be a woman. The selection committee will select the eligible beneficiaries strictly as per the following guidelines. II. Eligibility criteria The students of the Government and Aided Higher Secondary schools only are eligible for the BPL scholarship. Each school will be allotted a particular number of scholarships every year. The school selection committee shall select the eligible candidates from the applicants. The eligibility criterion of the scheme is merit cum means. Those students whose parents or guardians come under the BPL category and who have secured higher grades in their SSLC/any other equivalent examination are eligible to be selected for the scholarship. -

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT History Ponnani Is Popularly Known As “The Mecca of Kerala”

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT HISTORY Ponnani is popularly known as “the Mecca of Kerala”. As an ancient harbour city, it was a major trading hub in the Malabar region, the northernmost end of the state. There are many tales that try to explain how the place got its name. According to one, the prominent Brahmin family of Azhvancherry Thambrakkal once held sway over the land. During their heydays, they offered ponnu aana [elephants made of gold] to the temples, and this gave the land the name “Ponnani”. According to another, due to trade, ponnu [gold] from the Arab lands reached India for the first time at this place, and thus caused it to be named “Ponnani”. It is believed that a place that is referred to as “Tyndis” in the Greek book titled Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is Ponnani. However historians have not been able to establish the exact location of Tyndis beyond doubt. Nor has any archaeological evidence been recovered to confirm this belief. Politically too, Ponnani had great importance in the past. The Zamorins (rulers of Calicut) considered Ponnani as their second headquarters. When Tipu Sultan invaded Kerala in 1766, Ponnani was annexed to the Mysore kingdom. Later when the British colonized the land, Ponnani came under the Bombay Province for a brief interval of time. Still later, it was annexed Malabar and was considered part of the Madras Province for one-and-a-half centuries. Until 1861, Ponnani was the headquarters of Koottanad taluk, and with the formation of the state of Kerala in 1956, it became a taluk in Palakkad district. -

The Depictions of the Spice That Circumnavigated the Globe. the Contribution of Garcia De Orta's Colóquios Dos Simples (Goa

The depictions of the spice that circumnavigated the globe. The contribution of Garcia de Orta’s Colóquios dos Simples (Goa, 1563) to the construction of an entirely new knowledge about cloves Teresa Nobre de Carvalho1 University of Lisbon Abstract: Cloves have been prized since Ancient times for their agreeable smell and ther- apeutic properties. With the publication of Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas he Cousas Mediçinais da Índia (Goa, 1563), Garcia de Orta (c. 1500-1568) presented the first modern monographic study of cloves. In this analysis I wish to clarify what kind of information about Asian natural resources (cloves in particular) circulated in Europe, from Antiquity until the sixteenth century, and how the Portuguese medical treatises, led to the emer- gence of an innovative botanical discourse about tropical plants in Early Modern Europe. Keywords: cloves; Syzygium aromaticum L; Garcia de Orta; Early Modern Botany; Asian drugs and spices. Imagens da especiaria que circunavegou o globo O contributo dos colóquios dos simples de Garcia de Orta (Goa, 1563) à construção de um conhecimento totalmente novo sobre o cravo-da-índia. Resumo: O cravo-da-Índia foi estimado desde os tempos Antigos por seu cheiro agradável e propriedades terapêuticas. Com a publicação dos Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas, e Cousas Mediçinais da Índia (Goa, 1563), Garcia de Orta (1500-1568) apresentou o primeiro estudo monográfico moderno sobre tal especiaria. Nesta análise, gostaria de esclarecer que tipo de informação sobre os recursos naturais asiáticos (especiarias em particular) circulou na Eu- ropa, da Antiguidade até o século xvi, e como os tratados médicos portugueses levaram ao surgimento de um inovador discurso botânico sobre plantas tropicais na Europa moderna. -

Secrecy, Ostentation, and the Illustration of Exotic Animals in Sixteenth-Century Portugal

ANNALS OF SCIENCE, Vol. 66, No. 1, January 2009, 59Á82 Secrecy, Ostentation, and the Illustration of Exotic Animals in Sixteenth-Century Portugal PALMIRA FONTES DA COSTA Unit of History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, Faculty of Sciences and Technology, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2829-516 Campus da Caparica, Portugal Received 6 December 2007. Revised paper accepted 5 August 2008 Summary During the first decades of the sixteenth century, several animals described and viewed as exotic by the Europeans were regularly shipped from India to Lisbon. This paper addresses the relevance of these ‘new’ animals to knowledge and visual representations of the natural world. It discusses their cultural and scientific meaning in Portuguese travel literature of the period as well as printed illustrations, charts and tapestries. This paper suggests that Portugal did not make the most of its unique position in bringing news and animals from Asia. This was either because secrecy associated with trade and military interests hindered the diffusion of illustrations presented in Portuguese travel literature or because the illustrations commissioned by the nobility were represented on expensive media such as parchments and tapestries and remained treasured possessions. However, the essay also proposes that the Portuguese contributed to a new sense of the experience and meaning of nature and that they were crucial mediators in access to new knowledge and new ways of representing the natural world during this period. Contents 1. Introduction. ..........................................59 2. The place of exotic animals in Portuguese travel literature . ...........61 3. The place of exotic animals at the Portuguese Court.. ...............70 4. Exotic animals and political influence. -

Redalyc.Blackness and Heathenism. Color, Theology, and Race in The

Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura ISSN: 0120-2456 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Colombia MARCOCCI, GIUSEPPE Blackness and Heathenism. Color, Theology, and Race in the Portuguese World, c. 1450- 1600 Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura, vol. 43, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2016, pp. 33-57 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=127146460002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Blackness and Heathenism. Color, Theology, and Race in the Portuguese World, c. 1450-1600 doi: 10.15446/achsc.v43n2.59068 Negrura y gentilidad. Color, teología y raza en el mundo portugués, c. 1450-1600 Negrura e gentilidade. Cor, teologia e raça no mundo português, c. 1450-1600 giuseppe marcocci* Università della Tuscia Viterbo, Italia * [email protected] Artículo de investigación Recepción: 25 de febrero del 2016. Aprobación: 30 de marzo del 2016. Cómo citar este artículo Giuseppe Marcocci, “Blackness and Heathenism. Color, Theology, and Race in the Portuguese World, c. 1450-1600”, Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura 43.2: 33-57. achsc * Vol. 43 N.° 2, jul. - dic. 2016 * issN 0120-2456 (impreso) - 2256-5647 (eN líNea) * colombia * págs. 33-58 giuseppe marcocci [34] abstract The coexistence of a process of hierarchy and discrimination among human groups alongside dynamics of cultural and social hybridization in the Portuguese world in the early modern age has led to an intense historiographical debate. -

Migration from Bengal to Arakan During British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin

Occasional Paper Series Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin 2019 Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher Brussels This and other publications in TOAEP’s Occasional Paper Series may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site http://toaep.org, which uses Persistent URLs for all publications it makes available (such PURLs will not be changed). This publication was first published on 6 December 2019. © Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2019 All rights are reserved. You may read, print or download this publication or any part of it from http://www.toaep.org/ for personal use, but you may not in any way charge for its use by others, directly or by reproducing it, storing it in a retrieval system, transmitting it, or utilising it in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, in whole or in part, without the prior permis- sion in writing of the copyright holder. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the copyright holder. You must not circulate this publication in any other cover and you must impose the same condition on any ac- quirer. You must not make this publication or any part of it available on the Internet by any other URL than that on http://www.toaep.org/, without permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-82-8348-150-1. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 2 2. Setting the Scene: The 1911, 1921 and 1931 Censuses of British Burma ............................ -

A Construçao Do Conhecimento

MAPAS E ICONOGRAFIA DOS SÉCS. XVI E XVII 1369 [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] Apêndices A armada de António de Abreu reconhece as ilhas de Amboino e Banda, 1511 Francisco Serrão reconhece Ternate (Molucas do Norte), 1511 Primeiras missões portuguesas ao Sião e a Pegu, 1. Cronologias 1511-1512 Jorge Álvares atinge o estuário do “rio das Pérolas” a bordo de um junco chinês, Junho I. Cronologia essencial da corrida de 1513 dos europeus para o Extremo Vasco Núñez de Balboa chega ao Oceano Oriente, 1474-1641 Pacífico, Setembro de 1513 As acções associadas de modo directo à Os portugueses reconhecem as costas do China a sombreado. Guangdong, 1514 Afonso de Albuquerque impõe a soberania Paolo Toscanelli propõe a Portugal plano para portuguesa em Ormuz e domina o Golfo atingir o Japão e a China pelo Ocidente, 1574 Pérsico, 1515 Diogo Cão navega para além do cabo de Santa Os portugueses começam a frequentar Solor e Maria (13º 23’ lat. S) e crê encontrar-se às Timor, 1515 portas do Índico, 1482-1484 Missão de Fernão Peres de Andrade a Pêro da Covilhã parte para a Índia via Cantão, levando a embaixada de Tomé Pires Alexandria para saber das rotas e locais de à China, 1517 comércio do Índico, 1487 Fracasso da embaixada de Tomé Pires; os Bartolomeu Dias dobra o cabo da Boa portugueses são proibidos de frequentar os Esperança, 1488 portos chineses; estabelecimento do comércio Cristóvão Colombo atinge as Antilhas e crê luso ilícito no Fujian e Zhejiang, 1521 encontrar-se nos confins -

Who W Rote About Sati Name Of

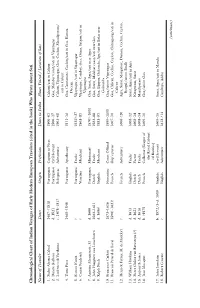

Chronological Chart of Indian Voyages of Early Modern European Travelers (cited in the book) Who Wrote about Sati Name of Traveler Dates Origin Profession Dates in India Places Visited / Location of Sati 1. Pedro Alvares Cabral 1467–?1518 Portuguese Captain of Fleet 1500–01 Calicut/sati in Calicut 2. Duarte Barbosa d. 1521 Portuguese Civil Servant 1500–17 Goa, Malabar Coast/sati in Vijaynagar 3. Ludovico di Varthema c. 1475–1517 Bolognese Adventurer 1503–08 Calicut, Vijaynagar, Goa, Cochin, Masulipatam/ sati in Calicut 4. Tome Pires 1468–1540 Portuguese Apothecary 1511–16 Goa, Cannanore, Cochin/sati in Goa, Kanara, Deccan 5. Fernao Nuniz ? Portuguese Trader 1535?–37 Vijaynagar/sati in Vijaynagar 6. Caesar Frederick ? Venetian Merchant 1563–81 Vijaynagar, Cambay, Goa, Orissa, Satgan/sati in Vijaynagar 7. Antoine Monserrate, SJ d. 1600 Portuguese Missionary 1570?–1600 Goa, Surat, Agra/sati near Agra 8. John Huyghen van Linschoten 1563–1611 Dutch Trader 1583–88 Goa, Surat, Malabar coast/sati near Goa 9. Ralph Fitch d. 1606? English Merchant 1583–91 Goa, Bijapur, Golconda, Agr/sati in Bidar near Golconda 10. Francesco Carletti 1573–1636 Florentine Court Official 1599–1601 Goa/sati in Vijaynagar 11. Francois Pyrard de Laval 1590?–1621? French Ship’s purser 1607–10 Goa, Calicut, Cochin, Ceylon, Chittagong/sati in Calicut 12. Henri de Feynes, M. de Montfort ? French Adventurer 1608–?20 Agra, Surat, Mangalore, Daman, Cochin, Ceylon, Bengal/sati in Sindh 13. William Hawkins d. 1613 English Trader 1608–12 Surat, Agra/sati in Agra 14. Pieter Gielisz van Ravesteyn (?) d. 1621 Dutch Factor 1608–14 Nizapatam, Surat 15. -

John FT Keane's Late Nineteenth Century Ḥajj by Nicole J. Crisp BA

Out of Obscurity: John F. T. Keane’s Late Nineteenth Century Ḥajj by Nicole J. Crisp B.A. in History, May 2014, University of Nevada, Las Vegas B.A. in Anthropology, May 2014, University of Nevada, Las Vegas A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts May 21, 2017 Thesis directed by Dina Rizk Khoury Professor of History © Copyright 2017 by Nicole J. Crisp All rights reserved ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professors Khoury and Blecher specifically for guiding me through the journey of writing this thesis as well as the rest of the George Washington University’s History Department whose faculty, students, and staff have created an unforgettable learning experience over the past three years. Further, I would like to thank my co-workers, both in College Park, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., some of whom have become like family to me and helped me through thick and thin. I would also be remiss if I were not to thank my best friend, Danielle Romero, who mentioned me in the acknowledgements page of her thesis so I effectively must mention her here and quote a line from series that got me through the end of this thesis, “Bang.” I would also like to express my gratitude to my Aunt Joy Harris who has been a constant fountain of encouragement. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, Larry and Dianne, to whom this thesis is dedicated.