The Role of Charts in Islamic Navigation in the Indian Ocean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms Among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar

JIOWSJournal of Indian Ocean World Studies An Abode of Islam under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar Mahmood Kooria To cite this article: Kooria, Mahmood. “An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar.” Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies, 1 (2017), pp. 89-109. More information about the Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies can be found at: jiows.mcgill.ca © Mahmood Kooria. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Li- cense CC BY NC SA, which permits users to share, use, and remix the material provide they give proper attribu- tion, the use is non-commercial, and any remixes/transformations of the work are shared under the same license as the original. Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies, 1 (2017), pp. 89-109. © Mahmood Kooria, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 | 89 An Abode of Islam under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar Mahmood Kooria* Leiden University, Netherlands ABSTRACT When Vasco da Gama asked the Zamorin (ruler) of Calicut to expel from his domains all Muslims hailing from Cairo and the Red Sea, the Zamorin rejected it, saying that they were living in his kingdom “as natives, not foreigners.” This was a marker of reciprocal understanding between Muslims and Zamorins. When war broke out with the Portuguese, Muslim intellectuals in the region wrote treatises and delivered sermons in order to mobilize their community in support of the Zamorins. -

The Depictions of the Spice That Circumnavigated the Globe. the Contribution of Garcia De Orta's Colóquios Dos Simples (Goa

The depictions of the spice that circumnavigated the globe. The contribution of Garcia de Orta’s Colóquios dos Simples (Goa, 1563) to the construction of an entirely new knowledge about cloves Teresa Nobre de Carvalho1 University of Lisbon Abstract: Cloves have been prized since Ancient times for their agreeable smell and ther- apeutic properties. With the publication of Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas he Cousas Mediçinais da Índia (Goa, 1563), Garcia de Orta (c. 1500-1568) presented the first modern monographic study of cloves. In this analysis I wish to clarify what kind of information about Asian natural resources (cloves in particular) circulated in Europe, from Antiquity until the sixteenth century, and how the Portuguese medical treatises, led to the emer- gence of an innovative botanical discourse about tropical plants in Early Modern Europe. Keywords: cloves; Syzygium aromaticum L; Garcia de Orta; Early Modern Botany; Asian drugs and spices. Imagens da especiaria que circunavegou o globo O contributo dos colóquios dos simples de Garcia de Orta (Goa, 1563) à construção de um conhecimento totalmente novo sobre o cravo-da-índia. Resumo: O cravo-da-Índia foi estimado desde os tempos Antigos por seu cheiro agradável e propriedades terapêuticas. Com a publicação dos Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas, e Cousas Mediçinais da Índia (Goa, 1563), Garcia de Orta (1500-1568) apresentou o primeiro estudo monográfico moderno sobre tal especiaria. Nesta análise, gostaria de esclarecer que tipo de informação sobre os recursos naturais asiáticos (especiarias em particular) circulou na Eu- ropa, da Antiguidade até o século xvi, e como os tratados médicos portugueses levaram ao surgimento de um inovador discurso botânico sobre plantas tropicais na Europa moderna. -

Who W Rote About Sati Name Of

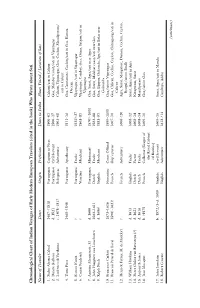

Chronological Chart of Indian Voyages of Early Modern European Travelers (cited in the book) Who Wrote about Sati Name of Traveler Dates Origin Profession Dates in India Places Visited / Location of Sati 1. Pedro Alvares Cabral 1467–?1518 Portuguese Captain of Fleet 1500–01 Calicut/sati in Calicut 2. Duarte Barbosa d. 1521 Portuguese Civil Servant 1500–17 Goa, Malabar Coast/sati in Vijaynagar 3. Ludovico di Varthema c. 1475–1517 Bolognese Adventurer 1503–08 Calicut, Vijaynagar, Goa, Cochin, Masulipatam/ sati in Calicut 4. Tome Pires 1468–1540 Portuguese Apothecary 1511–16 Goa, Cannanore, Cochin/sati in Goa, Kanara, Deccan 5. Fernao Nuniz ? Portuguese Trader 1535?–37 Vijaynagar/sati in Vijaynagar 6. Caesar Frederick ? Venetian Merchant 1563–81 Vijaynagar, Cambay, Goa, Orissa, Satgan/sati in Vijaynagar 7. Antoine Monserrate, SJ d. 1600 Portuguese Missionary 1570?–1600 Goa, Surat, Agra/sati near Agra 8. John Huyghen van Linschoten 1563–1611 Dutch Trader 1583–88 Goa, Surat, Malabar coast/sati near Goa 9. Ralph Fitch d. 1606? English Merchant 1583–91 Goa, Bijapur, Golconda, Agr/sati in Bidar near Golconda 10. Francesco Carletti 1573–1636 Florentine Court Official 1599–1601 Goa/sati in Vijaynagar 11. Francois Pyrard de Laval 1590?–1621? French Ship’s purser 1607–10 Goa, Calicut, Cochin, Ceylon, Chittagong/sati in Calicut 12. Henri de Feynes, M. de Montfort ? French Adventurer 1608–?20 Agra, Surat, Mangalore, Daman, Cochin, Ceylon, Bengal/sati in Sindh 13. William Hawkins d. 1613 English Trader 1608–12 Surat, Agra/sati in Agra 14. Pieter Gielisz van Ravesteyn (?) d. 1621 Dutch Factor 1608–14 Nizapatam, Surat 15. -

Alexander the Great

RESOURCE GUIDE Booth Library Eastern Illinois University Alexander the Great A Selected List of Resources Booth Library has a large collection of learning resources to support the study of Alexander the Great by undergraduates, graduates and faculty. These materials are held in the reference collection, the main book holdings, the journal collection and the online full-text databases. Books and journal articles from other libraries may be obtained using interlibrary loan. This is a subject guide to selected works in this field that are held by the library. The citations on this list represent only a small portion of the available literature owned by Booth Library. Additional materials can be found by searching the EIU Online Catalog. To find books, browse the shelves in these call numbers for the following subject areas: DE1 to DE100 History of the Greco-Roman World DF10 to DF951 History of Greece DF10 to DF289 Ancient Greece DF232.5 to DF233.8 Macedonian Epoch. Age of Philip. 359-336 B.C. DF234 to DF234.9 Alexander the Great, 336-323 B.C. DF235 to DF238.9 Hellenistic Period, 323-146.B.C. REFERENCE SOURCES Cambridge Companion to the Hellenistic World ………………………………………. Ref DE86 .C35 2006 Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World ……………………………………………… Ref DF16 .S23 1995 Who’s Who in the Greek World ……………………………………………………….. Stacks DE7.H39 2000 PLEASE REFER TO COLLECTION LOCATION GUIDE FOR LOCATION OF ALL MATERIALS ALEXANDER THE GREAT Alexander and His Successors ………………………………………………... Stacks DF234 .A44 2009x Alexander and the Hellenistic World ………………………………………………… Stacks DE83 .W43 Alexander the Conqueror: The Epic Story of the Warrior King ……………….. -

|||GET||| Alexander the Great: the Anabasis and the Indica 1St Edition

ALEXANDER THE GREAT: THE ANABASIS AND THE INDICA 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Arrian | 9780191633140 | | | | | Alexander the Great Josephus Vita ipsius Please follow the detailed Help center instructions to transfer the files to supported eReaders. Siege and Capture of Miletus. Lastly readers will also find three invaluable appendices, maps and site plans, and a comprehensive analytical index. Oxford University Press. Advanced embedding details, examples, and help! Campaign against the Mallians. His publications include commentaries on Curtius Rufus's histories of Alexander, including the introduction and commentary to accompany John Yardley's translation of Book 10 for the Clarendon Ancient History Series. Digression Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica 1st edition India. Capture of the Rock of Chorienes. Chapter I. A dramatic fast-moving story, told with great narrative skill, his work is now our prime and most detailed source for the history of Alexander--a compelling account of an exceptional leader, brilliant, ruthless, passionate, and complex. Views Read Edit View history. Book Description Paperback. Siege of Tyre. CMacedonian Expansion Greece : B. Destruction of Halicarnassus. The only complete English translation of Arrian available online is a rather antiquated translation by E. Facius; both E. Retrieved Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica 1st edition This manual of the Stoic moral philosophy was very popular, both among Pagans and Christians, for many centuries. Book Description Condition: New. Arrian c. Different authors have given different accounts of Alexander's life; and there is no one about whom more have written, or more at variance with each other. Ten Thousand Macedonians sent Home witli Craterus. -

John FT Keane's Late Nineteenth Century Ḥajj by Nicole J. Crisp BA

Out of Obscurity: John F. T. Keane’s Late Nineteenth Century Ḥajj by Nicole J. Crisp B.A. in History, May 2014, University of Nevada, Las Vegas B.A. in Anthropology, May 2014, University of Nevada, Las Vegas A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts May 21, 2017 Thesis directed by Dina Rizk Khoury Professor of History © Copyright 2017 by Nicole J. Crisp All rights reserved ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professors Khoury and Blecher specifically for guiding me through the journey of writing this thesis as well as the rest of the George Washington University’s History Department whose faculty, students, and staff have created an unforgettable learning experience over the past three years. Further, I would like to thank my co-workers, both in College Park, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., some of whom have become like family to me and helped me through thick and thin. I would also be remiss if I were not to thank my best friend, Danielle Romero, who mentioned me in the acknowledgements page of her thesis so I effectively must mention her here and quote a line from series that got me through the end of this thesis, “Bang.” I would also like to express my gratitude to my Aunt Joy Harris who has been a constant fountain of encouragement. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, Larry and Dianne, to whom this thesis is dedicated. -

List of Works Cited

List of Works Cited This is a simple list of the works quoted or mentioned in the foregoing text or notes. Where a work not originally written in English has been translated, the best available English edition is the one listed; otherwise, the best available edition in the original language. I Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, ed. A. Evans: La practica della merca tura, Cambridge, Mass., 1936. H. Yule, ed.: Cathay and the Way Thither, 3 vols., znd edn, London, 1913-16. Marco Polo, ed. A. C. Moule and Paul Pelliot: The Description of the World, 2 vols., London, 1938. Pierre d'Ailly, trans. Edwin F. Keever: Imago Mundi, Wilmington N.C., 1948. Joannes de Sacro Bosco (John of Holywood), ed. Joaquin Bensaude: "Tractado da sphera do mundo," in Regimento do astrolabio e do quadrante, Munich, 1914. (Facsimile edition of the unique Munich copy of the earliest printed navigation manual.) Claudius Ptolemaeus, ed. and trans. E. L. Stevenson: The Geography of Claudius Ptolemy, New York, 1932. Roger Bacon, ed. and trans. Robert B. Burke: Opus majus, Oxford, 1928. Ibn Battuta, ed. and trans. H. A. R. Gibb: The Travels of Ibn Battuta, vols. I and II, Cambridge, 1958-62. II Malcolm Letts, ed. and trans.: Mandeville's Travels, Texts and Transla tions, 2 vols., London, 1953. ]66 LIST OF WORKS CITED R. H. Major, ed.: India in the Fifteenth Century, London, I857: "The travels of Nicolo de' Conti ... as related by Poggio Bracciolini, in his work entitled Historia de varietate fortunae, Lib IV." III Gomes Eannes de Azurara, ed. Charles Raymond Beazley and Edgar Prestage. -

Fifteenth-Century Italian Travel Writings on India

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Vol. 13, No. 1, January-March, 2021. 1-12 Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V13/n1/v13n133.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v13n1.33 Published on March 28, 2021 India nel quattrocento: Fifteenth-Century Italian Travel Writings on India Jitamanyu Das Doctoral Candidate (JRF), Department of English, Jadavpur University, ORCID: 0000-0001- 5845-8098, [email protected], Abstract Fifteenth-century Italian travel narratives on India by Nicolò dei Conti and Gerolamo di Santo Stefano present a detailed account of the India they visited, following the narrative tradition of the Italian Marco Polo. These narratives of the Renaissance were published as descriptive authorial texts of travellers to the East. Their importance was due to the authors’ detailed first-hand experiences of the societies and cultures that they encountered, as well as the various trade centres of the period. These narratives were utilised by merchants, explorers, and Jesuits for a variety of purposes. The narratives of Nicolò dei Conti and Gerolamo di Santo Stefano thus became indispensable tools that were later distorted through numerous translations to suit the politics of Orientalism for the emerging colonial enterprises. In my paper, I have attempted a re-reading of the particular texts to identify how Italy saw India, while illustrating through their history of publication the transformation that these narratives underwent later in order to objectify India in the West through the lens of Orientalism in their manner of representation. Keywords: India, Italian Travel Writing, Orientalism, Renaissance, Translation The study of Western approaches towards India and the Indian Ocean Region has gone through a noteworthy shift in the last few decades. -

Repor T Resumes

REPOR TRESUMES ED 017 908 48 AL 000 990 CHAPTERS IN INDIAN CIVILIZATION--A HANDBOOK OF READINGS TO ACCOMPANY THE CIVILIZATION OF INDIA SYLLABUS. VOLUME II, BRITISH AND MODERN INDIA. BY- ELDER, JOSEPH W., ED. WISCONSIN UNIV., MADISON, DEPT. OF INDIAN STUDIES REPORT NUMBER BR-6-2512 PUB DATE JUN 67 CONTRACT OEC-3-6-062512-1744 EDRS PRICE MF-$1.25 HC-$12.04 299P. DESCRIPTORS- *INDIANS, *CULTURE, *AREA STUDIES, MASS MEDIA, *LANGUAGE AND AREA CENTERS, LITERATURE, LANGUAGE CLASSIFICATION, INDO EUROPEAN LANGUAGES, DRAMA, MUSIC, SOCIOCULTURAL PATTERNS, INDIA, THIS VOLUME IS THE COMPANION TO "VOLUME II CLASSICAL AND MEDIEVAL INDIA," AND IS DESIGNED TO ACCOMPANY COURSES DEALING WITH INDIA, PARTICULARLY THOSE COURSES USING THE "CIVILIZATION OF INDIA SYLLABUS"(BY THE SAME AUTHOR AND PUBLISHERS, 1965). VOLUME II CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING SELECTIONS--(/) "INDIA AND WESTERN INTELLECTUALS," BY JOSEPH W. ELDER,(2) "DEVELOPMENT AND REACH OF MASS MEDIA," BY K.E. EAPEN, (3) "DANCE, DANCE-DRAMA, AND MUSIC," BY CLIFF R. JONES AND ROBERT E. BROWN,(4) "MODERN INDIAN LITERATURE," BY M.G. KRISHNAMURTHI, (5) "LANGUAGE IDENTITY--AN INTRODUCTION TO INDIA'S LANGUAGE PROBLEMS," BY WILLIAM C. MCCORMACK, (6) "THE STUDY OF CIVILIZATIONS," BY JOSEPH W. ELDER, AND(7) "THE PEOPLES OF INDIA," BY ROBERT J. AND BEATRICE D. MILLER. THESE MATERIALS ARE WRITTEN IN ENGLISH AND ARE PUBLISHED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF INDIAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN, MADISON, WISCONSIN 53706. (AMM) 11116ro., F Bk.--. G 2S12 Ye- CHAPTERS IN INDIAN CIVILIZATION JOSEPH W ELDER Editor VOLUME I I BRITISH AND MODERN PERIOD U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

Built on Diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12Th-16Th

Built on diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12th-16th centuries AD) Jorge de Torres Rodriguez A 06 Built on diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12th-16th centuries AD) Construido sobre la diversidad: las estructuras estatales medievales de Somalilandia (siglos XII a XVI) Jorge de Torres Rodriguez Resumen Este artículo pretende ofrecer una visión general de la arqueología medieval mu- sulmana en el Cuerno de África, poniendo énfasis en el papel de los estados me- dievales que durante más de tres siglos fueron capaces de integrar poblaciones con creencias, estilos de vida, lenguas y etnias muy diferentes. El estudio combi- na fuentes históricas y arqueológicas para analizar el caso específico del oeste de Somalilandia, una región en la que grupos sedentarios y nómadas con culturas ma- teriales muy diferentes convivieron durante siglos. A través del análisis de las rela- ciones entre estos dos grupos se plantea una propuesta sobre el modo en que los estados musulmanes fueron capaces de proporcionar unas marco estable y cohesio- nado para la región durante toda la Edad Media. Palabras clave: Cuerno de África, Edad Media, Estados, Islam, Arqueología medie- val, nómadas Abstract This article presents an overview of the current situation of the medieval Islamic archaeology of the Horn of Africa, paying especial attention to the role of the me- dieval states that for more than three centuries were able to integrate peoples with very different beliefs, lifestyles, languages and ethnicities. The study combines his- torical and archaeological sources to analyze a specific case in western Somaliland, a region where nomads and urban dwellers –two groups with very different material cultures- lived together for centuries. -

Hymenoptera), New to the Iranian Fauna Majid FALLAHZADEH1, Ovidiu POPOVICI2, *

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle «Grigore Antipa» Vol. 59 (1) pp. 73–79 DOI: 10.1515/travmu-2016-0012 Research paper Doddiella Kieffer: a Peculiar Genus of Platygastroidea (Hymenoptera), New to the Iranian Fauna Majid FALLAHZADEH1, Ovidiu POPOVICI2, * 1Department of Entomology, Jahrom Branch, Islamic Azad University, Jahrom, Iran. 2University Al. I. Cuza, Faculty of Biology, Carol The First Avenue No. 11, Jassy, 700506 Romania. *corresponding author, e–mail: [email protected] Received: December 22, 2015; Accepted: March 25, 2016; Available online: June 26, 2016; Printed: June 30, 2016 Abstract. Doddiella kiefferi Priesner, 1951 (Hymenoptera, Platygastroidea) is here redescribed and illustrated to facilitate its identification. This is the first record of the peculiar genusDoddiella Kieffer, 1913 from Iran. The specimens were collected by Malaise traps from Fars province in southern Iran during 2012 and 2013. Iran is the north–eastern limit in the distribution of this species. Key Words: parasitoids, scelionid wasps, Malaise trap, Iran INTRODUCTION Platygastroidea in Iran is very poorly known. The majority of reports of the Scelionidae in Iran are related to the genus Trissolcus Ashmead (e.g. Radjabi & Amir Nazari, 1989; Radjabi, 2001; Hashemi Rad et al., 2002; Iranipour & Johnson, 2010) that are the best–known egg parasitoids of some pests on agricultural crops in Iran. No comprehensive study has been done on these beneficial insects in this region so far. More than a century ago Kieffer (1913) established the genus Doddiella in honor of the reputable entomologist A. P. Dodd. This genus was created as monotypic for its type species D. nigriceps Kieffer, 1913, collected from Ghana, Côte d’Or, Aburi. -

1 from Cultural Trauma to Transnational

FROM CULTURAL TRAUMA TO TRANSNATIONAL TRANSACTIONS: POLYCOLONIAL TRANSLATIONS IN SOUTH ASIA, WITH FOCUS ON BENGAL Saugata Bhaduri JNU Spectress Fellow at JU, Kraków, Poland Report on Research in Summary Form 1. Premise of the Research: There are some problems in the way colonial encounters and the resultant ‘cultural trauma’ have been theorized, which needs to be supplemented with the idea of what I call the ‘polycolonial’: a) The first problem – the usual ‘mononational’ understanding of colonialism: • A first problem in theorisations on colonialism is that the colonial encounter, and the resultant ‘cultural trauma’, is often seen as rather mononational, with the colonial history of a particular colonised nation being primarily ascribed to a single master colonising nation, e.g. England for South Asia, and especially Bengal. • This is obviously factually wrong, and there were more than one colonial power at work, and Bengal was colonised not by the English alone but by the Portuguese (1500-1632; in some parts of South Asia till 1961), the Dutch (1625-1825), the Danish (1698-1857), and the French (1673-1950) , while the British colonial era begins in 1757 and its cultural enterprises only by the 1830s (though they were in Bengal by the 1650s). Besides the Germans, Italians, and travellers from other European nations, including Poland, also played major roles in South Asia’s tryst with colonial modernity from the 14th to the 20th century. It is this plural experience of cultural encounter that I call the 'polycolonial'. b) The second problem – colonial encounters understood mostly in Manichaean terms: • A second problem in theorisations on colonialism is that the colonial encounter and the epistemic violence caused by colonial ideological activities is usually seen in negative and Manichaean terms, while actually the 'cultural trauma' generated through polycolonial encounters proved to be rather productive in the South Asian context.