John FT Keane's Late Nineteenth Century Ḥajj by Nicole J. Crisp BA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms Among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar

JIOWSJournal of Indian Ocean World Studies An Abode of Islam under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar Mahmood Kooria To cite this article: Kooria, Mahmood. “An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar.” Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies, 1 (2017), pp. 89-109. More information about the Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies can be found at: jiows.mcgill.ca © Mahmood Kooria. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Li- cense CC BY NC SA, which permits users to share, use, and remix the material provide they give proper attribu- tion, the use is non-commercial, and any remixes/transformations of the work are shared under the same license as the original. Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies, 1 (2017), pp. 89-109. © Mahmood Kooria, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 | 89 An Abode of Islam under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar Mahmood Kooria* Leiden University, Netherlands ABSTRACT When Vasco da Gama asked the Zamorin (ruler) of Calicut to expel from his domains all Muslims hailing from Cairo and the Red Sea, the Zamorin rejected it, saying that they were living in his kingdom “as natives, not foreigners.” This was a marker of reciprocal understanding between Muslims and Zamorins. When war broke out with the Portuguese, Muslim intellectuals in the region wrote treatises and delivered sermons in order to mobilize their community in support of the Zamorins. -

The Depictions of the Spice That Circumnavigated the Globe. the Contribution of Garcia De Orta's Colóquios Dos Simples (Goa

The depictions of the spice that circumnavigated the globe. The contribution of Garcia de Orta’s Colóquios dos Simples (Goa, 1563) to the construction of an entirely new knowledge about cloves Teresa Nobre de Carvalho1 University of Lisbon Abstract: Cloves have been prized since Ancient times for their agreeable smell and ther- apeutic properties. With the publication of Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas he Cousas Mediçinais da Índia (Goa, 1563), Garcia de Orta (c. 1500-1568) presented the first modern monographic study of cloves. In this analysis I wish to clarify what kind of information about Asian natural resources (cloves in particular) circulated in Europe, from Antiquity until the sixteenth century, and how the Portuguese medical treatises, led to the emer- gence of an innovative botanical discourse about tropical plants in Early Modern Europe. Keywords: cloves; Syzygium aromaticum L; Garcia de Orta; Early Modern Botany; Asian drugs and spices. Imagens da especiaria que circunavegou o globo O contributo dos colóquios dos simples de Garcia de Orta (Goa, 1563) à construção de um conhecimento totalmente novo sobre o cravo-da-índia. Resumo: O cravo-da-Índia foi estimado desde os tempos Antigos por seu cheiro agradável e propriedades terapêuticas. Com a publicação dos Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas, e Cousas Mediçinais da Índia (Goa, 1563), Garcia de Orta (1500-1568) apresentou o primeiro estudo monográfico moderno sobre tal especiaria. Nesta análise, gostaria de esclarecer que tipo de informação sobre os recursos naturais asiáticos (especiarias em particular) circulou na Eu- ropa, da Antiguidade até o século xvi, e como os tratados médicos portugueses levaram ao surgimento de um inovador discurso botânico sobre plantas tropicais na Europa moderna. -

Who W Rote About Sati Name Of

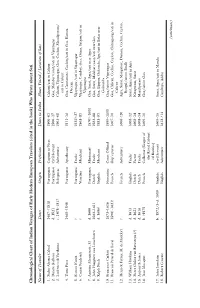

Chronological Chart of Indian Voyages of Early Modern European Travelers (cited in the book) Who Wrote about Sati Name of Traveler Dates Origin Profession Dates in India Places Visited / Location of Sati 1. Pedro Alvares Cabral 1467–?1518 Portuguese Captain of Fleet 1500–01 Calicut/sati in Calicut 2. Duarte Barbosa d. 1521 Portuguese Civil Servant 1500–17 Goa, Malabar Coast/sati in Vijaynagar 3. Ludovico di Varthema c. 1475–1517 Bolognese Adventurer 1503–08 Calicut, Vijaynagar, Goa, Cochin, Masulipatam/ sati in Calicut 4. Tome Pires 1468–1540 Portuguese Apothecary 1511–16 Goa, Cannanore, Cochin/sati in Goa, Kanara, Deccan 5. Fernao Nuniz ? Portuguese Trader 1535?–37 Vijaynagar/sati in Vijaynagar 6. Caesar Frederick ? Venetian Merchant 1563–81 Vijaynagar, Cambay, Goa, Orissa, Satgan/sati in Vijaynagar 7. Antoine Monserrate, SJ d. 1600 Portuguese Missionary 1570?–1600 Goa, Surat, Agra/sati near Agra 8. John Huyghen van Linschoten 1563–1611 Dutch Trader 1583–88 Goa, Surat, Malabar coast/sati near Goa 9. Ralph Fitch d. 1606? English Merchant 1583–91 Goa, Bijapur, Golconda, Agr/sati in Bidar near Golconda 10. Francesco Carletti 1573–1636 Florentine Court Official 1599–1601 Goa/sati in Vijaynagar 11. Francois Pyrard de Laval 1590?–1621? French Ship’s purser 1607–10 Goa, Calicut, Cochin, Ceylon, Chittagong/sati in Calicut 12. Henri de Feynes, M. de Montfort ? French Adventurer 1608–?20 Agra, Surat, Mangalore, Daman, Cochin, Ceylon, Bengal/sati in Sindh 13. William Hawkins d. 1613 English Trader 1608–12 Surat, Agra/sati in Agra 14. Pieter Gielisz van Ravesteyn (?) d. 1621 Dutch Factor 1608–14 Nizapatam, Surat 15. -

PDF Facsimile Vol. 2

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com PersonalnarrativeofapilgrimagetoEl-MedinahandMeccah RichardFrancisBurton W/. <J\ From the library of Lloyd Cabot Ttriggs 1909 - 1975 Tozzer Library PEABODY MUSEUM HARVARD UNIVERSITY f. THE PILGRIM. PERSONAL NARRATIVE PILGKIMAGE TO EL-MEDINAH AND MECCAH. BY RICHARD F, BURTON, LIEUTENANT BOMBAY ARHY. " Om aotlons of Mecca must be (lrnwn from the Arabluis -, u no unbclierer is permitted to enter the city, our traveller* are eilent." — Gibbon, chap. 50. IN THREE VOLUMES. VOL. II. — EL-MEDINAH. LONDON: LONGMAN, BROWN, GREEN, AND LONGMANS. 18H5. '/•'.< Author r«ftn«4 to hitnsetfttic right o/aufAorumff a TransIatfon ofthiM Work.] Bool. R-m>^'*fsV •• RECEIVED QTO 1 r ^f( _PEABODY "MUSEUM XiONDON I A. tuid G. A. SromswooDE, New. street-Squure. ^J \ CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME. CHAPTER XIV. PAGE From Bir Abbas to El Mcdinah - - - 1 CHAPTER XV. Through the Suburb of El Medinah to Hamid's House - - - - - 28 CHAPTER XVI. A Visit to the Prophet's Tomb - . - 56 CHAPTER XVII. An Essay towards the History of the Prophet's Mosque - - - - 113 CHAPTER XVIII. El Medinah 162 CHAPTER XIX. A Ride to the Mosque of Kuba - - - 195 CHAPTER XX. The Visitation of Hamzah's Tomb - - 223 CHAPTER XXI. The People of El Medinah - - - 254 IV CONTENTS. CHAPTER XXII. FACE A Visit to the Saints' Cemetery - - - 295 POSTSCRIPT - 329 APPENDIX I. Specimen of a Murshid's Diploma, in the Kadiri Oriler of the Mystic Craft El Tasawwuf - - - 341 APPENDIX II. -

Encounters at the Seams

Jen Barrer-Gall 5 April 2013 Advisor: Professor William Leach Second Reader: Professor Christopher Brown Encounters at the Seams English "Self Fashioning" in the Ottoman World, 1563-1718 1 Acknowledgments I thank Professor William Leach for his encouragement and help throughout this process. His thesis seminar was a place in which students could freely discuss their papers and give advice to their peers. Moreover, I thank Professor Leach for reminding us that history is as much about the story we are telling as it is about whom we are as individuals. I also thank my second reader, Professor Christopher Brown, whose course "England and the Wider World" inspired me to major in history. He has always been patient and supportive, and I cannot thank him enough for all his advice relating to reading, analyzing, and writing history. 2 Introduction 4 An Eastern Door Opens Chapter I 11 Traders and Travelers on the Ottoman Stage An Appetite for Knowledge Ottoman Dress as a Business Tool Unwritten Customs Moments of Vulnerability, Moments of Pride Chapter II 27 Englishmen in Captivity: How they coped and how they escaped Telling their Tale Seized, Stripped, and Vulnerable The Great Escape Performative Conversion Chapter III 39 Renegades at Sea, on Land, and on the Stage A Place of Intrigue The Seventeenth-Century Imagination Becoming East Conclusion 55 Changing Landscapes Appendix 60 Bibliography 65 3 Introduction An Eastern Door Opens In 1575, six years before Queen Elizabeth I signed the Levant Company charter, English merchants ventured to Constantinople to renew an Eastern trade that had been dormant for nearly twenty years. -

List of Works Cited

List of Works Cited This is a simple list of the works quoted or mentioned in the foregoing text or notes. Where a work not originally written in English has been translated, the best available English edition is the one listed; otherwise, the best available edition in the original language. I Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, ed. A. Evans: La practica della merca tura, Cambridge, Mass., 1936. H. Yule, ed.: Cathay and the Way Thither, 3 vols., znd edn, London, 1913-16. Marco Polo, ed. A. C. Moule and Paul Pelliot: The Description of the World, 2 vols., London, 1938. Pierre d'Ailly, trans. Edwin F. Keever: Imago Mundi, Wilmington N.C., 1948. Joannes de Sacro Bosco (John of Holywood), ed. Joaquin Bensaude: "Tractado da sphera do mundo," in Regimento do astrolabio e do quadrante, Munich, 1914. (Facsimile edition of the unique Munich copy of the earliest printed navigation manual.) Claudius Ptolemaeus, ed. and trans. E. L. Stevenson: The Geography of Claudius Ptolemy, New York, 1932. Roger Bacon, ed. and trans. Robert B. Burke: Opus majus, Oxford, 1928. Ibn Battuta, ed. and trans. H. A. R. Gibb: The Travels of Ibn Battuta, vols. I and II, Cambridge, 1958-62. II Malcolm Letts, ed. and trans.: Mandeville's Travels, Texts and Transla tions, 2 vols., London, 1953. ]66 LIST OF WORKS CITED R. H. Major, ed.: India in the Fifteenth Century, London, I857: "The travels of Nicolo de' Conti ... as related by Poggio Bracciolini, in his work entitled Historia de varietate fortunae, Lib IV." III Gomes Eannes de Azurara, ed. Charles Raymond Beazley and Edgar Prestage. -

Where Do the Multi-Religious Origins of Islam Lie? a Topological Approach to a Wicked Problem

9 (2019) Article 6: 165-210 Where Do the Multi-Religious Origins of Islam Lie? A Topological Approach to a Wicked Problem MANFRED SING Leibniz Institute of European History, Mainz, Germany This contribution to Entangled Religions is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC BY 4.0 International). The license can be accessed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. Entangled Religions 9 (2019) http://doi.org/10.13154/er.v9.2019.165–210 Where Do the Multi-Religious Origins of Islam Lie? Where Do the Multi-Religious Origins of Islam Lie? A Topological Approach to a Wicked Problem MANFRED SING Leibniz Institute of European History ABSTRACT The revelation of Islam in Arabic, its emergence in the Western Arabian Peninsula, and its acquaintance with Biblical literature seem to be clear indications for Islam’s birthplace and its religious foundations. While the majority of academic scholarship accepts the historicity of the revelation in Mecca and Medina, revisionist scholars have started questioning the location of early Islam with increasing fervour in recent years. Drawing on the isolation of Mecca and the lack of clear references to Mecca in ancient and non-Muslim literature before the mid-eighth century, these scholars have cast doubt on the claim that Mecca was already a trading outpost and a pilgrimage site prior to Islam, questioning the traditional Islamic and Orientalist view. Space, thus, plays a prominent role in the debate on the origins of Islam, although space is almost never conceptually discussed. In the following paper, I challenge the limited understanding of space in revisionist as well as mainstream scholarship. -

The Role of Charts in Islamic Navigation in the Indian Ocean

13 · The Role of Charts in Islamic Navigation in the Indian Ocean GERALD R. TIBBETTS The existence of indigenous navigational charts of the voyage.7 Barros wrote in the 1540s and could have read Indian Ocean is suggested by several early European Varthema's work, which was in many editions by that sources, the earliest of which is the brief mention of date, including an edition in Spanish published in Seville mariners' charts by Marco Polo. First, in connection with in 1520. There are other occasions when Barros seems Ceylon Polo mentions "la mapemondi des mariner de cel to have incorporated later materials into his version of mer,"! a reference that can only refer to a nautical map the earlier Portuguese accounts of the Indian Ocean, so of some sort. Second, in connection with the Indian west some doubt is cast on the accuracy of his statement. coast he refers to "Ie conpas e la scriture de sajes rnar In 1512 another possible local chart is mentioned by iner."2 This first word has been translated as "charts," Afonso de Albuquerque in a letter to the Portuguese king and strangely enough it is the very word (al-qunbii~) used Manuel. He reports that he had seen a large chart belong by Abmad ibn Majid (fl. A.D. 1460-1500) in connection ing to a pilot on which Brazil, the Indian Ocean, and the with portolan charts.3 Far East were shown. This chart can only have been very The other sources are Portuguese and come from the sketchy, for the Portuguese pilot Francisco Rodrigues period when that country had reached these parts. -

Fifteenth-Century Italian Travel Writings on India

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Vol. 13, No. 1, January-March, 2021. 1-12 Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V13/n1/v13n133.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v13n1.33 Published on March 28, 2021 India nel quattrocento: Fifteenth-Century Italian Travel Writings on India Jitamanyu Das Doctoral Candidate (JRF), Department of English, Jadavpur University, ORCID: 0000-0001- 5845-8098, [email protected], Abstract Fifteenth-century Italian travel narratives on India by Nicolò dei Conti and Gerolamo di Santo Stefano present a detailed account of the India they visited, following the narrative tradition of the Italian Marco Polo. These narratives of the Renaissance were published as descriptive authorial texts of travellers to the East. Their importance was due to the authors’ detailed first-hand experiences of the societies and cultures that they encountered, as well as the various trade centres of the period. These narratives were utilised by merchants, explorers, and Jesuits for a variety of purposes. The narratives of Nicolò dei Conti and Gerolamo di Santo Stefano thus became indispensable tools that were later distorted through numerous translations to suit the politics of Orientalism for the emerging colonial enterprises. In my paper, I have attempted a re-reading of the particular texts to identify how Italy saw India, while illustrating through their history of publication the transformation that these narratives underwent later in order to objectify India in the West through the lens of Orientalism in their manner of representation. Keywords: India, Italian Travel Writing, Orientalism, Renaissance, Translation The study of Western approaches towards India and the Indian Ocean Region has gone through a noteworthy shift in the last few decades. -

Repor T Resumes

REPOR TRESUMES ED 017 908 48 AL 000 990 CHAPTERS IN INDIAN CIVILIZATION--A HANDBOOK OF READINGS TO ACCOMPANY THE CIVILIZATION OF INDIA SYLLABUS. VOLUME II, BRITISH AND MODERN INDIA. BY- ELDER, JOSEPH W., ED. WISCONSIN UNIV., MADISON, DEPT. OF INDIAN STUDIES REPORT NUMBER BR-6-2512 PUB DATE JUN 67 CONTRACT OEC-3-6-062512-1744 EDRS PRICE MF-$1.25 HC-$12.04 299P. DESCRIPTORS- *INDIANS, *CULTURE, *AREA STUDIES, MASS MEDIA, *LANGUAGE AND AREA CENTERS, LITERATURE, LANGUAGE CLASSIFICATION, INDO EUROPEAN LANGUAGES, DRAMA, MUSIC, SOCIOCULTURAL PATTERNS, INDIA, THIS VOLUME IS THE COMPANION TO "VOLUME II CLASSICAL AND MEDIEVAL INDIA," AND IS DESIGNED TO ACCOMPANY COURSES DEALING WITH INDIA, PARTICULARLY THOSE COURSES USING THE "CIVILIZATION OF INDIA SYLLABUS"(BY THE SAME AUTHOR AND PUBLISHERS, 1965). VOLUME II CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING SELECTIONS--(/) "INDIA AND WESTERN INTELLECTUALS," BY JOSEPH W. ELDER,(2) "DEVELOPMENT AND REACH OF MASS MEDIA," BY K.E. EAPEN, (3) "DANCE, DANCE-DRAMA, AND MUSIC," BY CLIFF R. JONES AND ROBERT E. BROWN,(4) "MODERN INDIAN LITERATURE," BY M.G. KRISHNAMURTHI, (5) "LANGUAGE IDENTITY--AN INTRODUCTION TO INDIA'S LANGUAGE PROBLEMS," BY WILLIAM C. MCCORMACK, (6) "THE STUDY OF CIVILIZATIONS," BY JOSEPH W. ELDER, AND(7) "THE PEOPLES OF INDIA," BY ROBERT J. AND BEATRICE D. MILLER. THESE MATERIALS ARE WRITTEN IN ENGLISH AND ARE PUBLISHED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF INDIAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN, MADISON, WISCONSIN 53706. (AMM) 11116ro., F Bk.--. G 2S12 Ye- CHAPTERS IN INDIAN CIVILIZATION JOSEPH W ELDER Editor VOLUME I I BRITISH AND MODERN PERIOD U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

Built on Diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12Th-16Th

Built on diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12th-16th centuries AD) Jorge de Torres Rodriguez A 06 Built on diversity: Statehood in Medieval Somaliland (12th-16th centuries AD) Construido sobre la diversidad: las estructuras estatales medievales de Somalilandia (siglos XII a XVI) Jorge de Torres Rodriguez Resumen Este artículo pretende ofrecer una visión general de la arqueología medieval mu- sulmana en el Cuerno de África, poniendo énfasis en el papel de los estados me- dievales que durante más de tres siglos fueron capaces de integrar poblaciones con creencias, estilos de vida, lenguas y etnias muy diferentes. El estudio combi- na fuentes históricas y arqueológicas para analizar el caso específico del oeste de Somalilandia, una región en la que grupos sedentarios y nómadas con culturas ma- teriales muy diferentes convivieron durante siglos. A través del análisis de las rela- ciones entre estos dos grupos se plantea una propuesta sobre el modo en que los estados musulmanes fueron capaces de proporcionar unas marco estable y cohesio- nado para la región durante toda la Edad Media. Palabras clave: Cuerno de África, Edad Media, Estados, Islam, Arqueología medie- val, nómadas Abstract This article presents an overview of the current situation of the medieval Islamic archaeology of the Horn of Africa, paying especial attention to the role of the me- dieval states that for more than three centuries were able to integrate peoples with very different beliefs, lifestyles, languages and ethnicities. The study combines his- torical and archaeological sources to analyze a specific case in western Somaliland, a region where nomads and urban dwellers –two groups with very different material cultures- lived together for centuries. -

Pitts Story for Website

Joseph Pitts of Exon: the first Englishman in Mecca By Ghee Bowman, community researcher at Exeter Global Centre With thanks and acknowledgements to Paul Auchterlonie Joseph Pitts was born in Exeter around 1663, shortly after the restoration of Charles II. At the age of 15, Joseph was taken with a desire to travel - “my genius led me to be a sailor” as he puts it - and enrolled as one of a crew of six on the fishing boat Speedwell under the captain, George Taylor. They sailed on Easter Tuesday 1678, bound for the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, where they intended to catch fish for sale in Spain. In the Bay of Biscay, however, the boat was captured by Barbary pirates. The pirates sank the boat, as they subsequently did many others. They weren’t interested in the boat or its cargo, but only the people on it. What were Barbary pirates? Also known as Corsairs, they were privateers from ports in North Africa, who sailed the Mediterranean in search of people they could capture and sell as slaves. It is estimated that they captured around a million people from the 16 th to the 19 th century. Until the 17 th century they used galleys, powered by oars, and so were restricted to the Mediterranean. Around 1610 however, they developed the broad sails that enabled them to go into the Atlantic, due to the help of English sea captains who had left the country after Queen Elizabeth’s death. Kent-born Captain Jack Ward, for example, was active in Tunis at the time under the name Yusuf Reis.